Migration Then and Now: A European and UK Perspective

“No Turning Back” Migration Museum Project, London

Migration! What an ongoing catastrophe today. People drowning by the hundreds in the Mediterranean trying to get to Europe, people stranded in Calais, France who were trying to reach the UK; refugees stuck on the Island of Lesbos or in Northern Greece for years. Thousands of people in a camp outside of Paris, the EU cruelly closing its borders in violation of its principles, and in the UK, there is Brexit, anti immigrant fervor as ignorant and vehement as that in the US.

One of the best books I have read on this subject is The New Odyssey by Patrick Kinsley. As a Guardian reporter he was supported to go to the places where migration from Africa is occurring, to talk to smugglers, to follow people in Greece to the border of the EU

(both before and after it was closed), to meet people of all ages and talk to them and to point out how the EU policy is completely ineffective and inappropriate. He followed one man’s journey from Africa to Sweden.

The Migration Museum Project, based in Lambeth, South London, offers an historical perspective on UK migration. Its current exhibition, “No Turning Back” chooses “seven migration moments that changed Britain.” Although the exhibition is deliberately non chronological, I will put them in historical order.

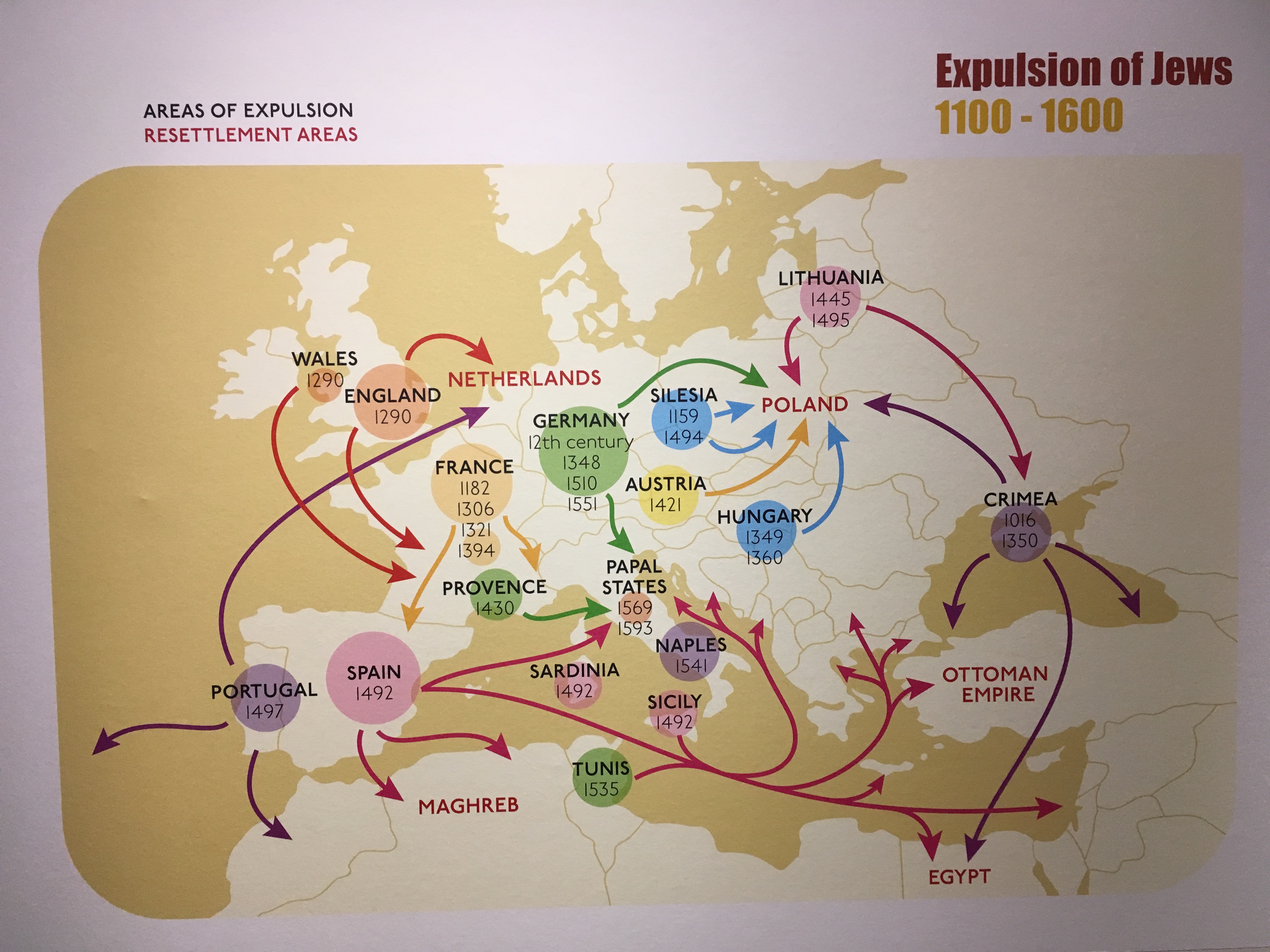

Multiple expulsions of the Jews 1100 – 1600

The earliest event, the expulsion of the Jews in 1209 (this was of course an emigration, not an immigration) followed on years of discrimination.

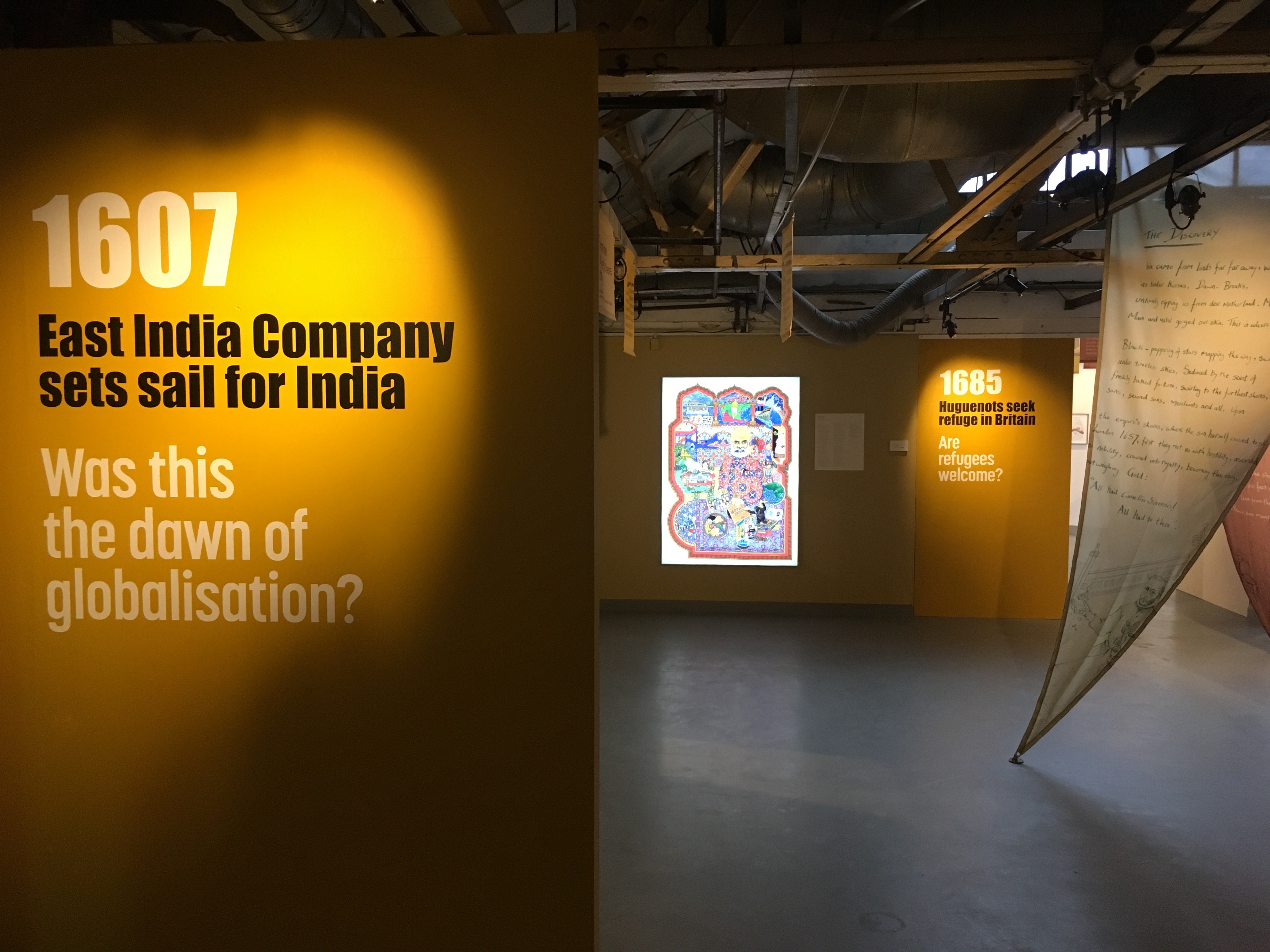

1607 is the year that the East India Company first went to India leading to centuries of complex migrations to and from England. This exhibition includes the stories of individuals and families of Anglo Indians, Gurkhas, and Lascars, three groups that participated in the British colonial project in different ways.

A huge immigration of Huguenots came to Britain in 1685 to seek refuge when they were expelled from France.

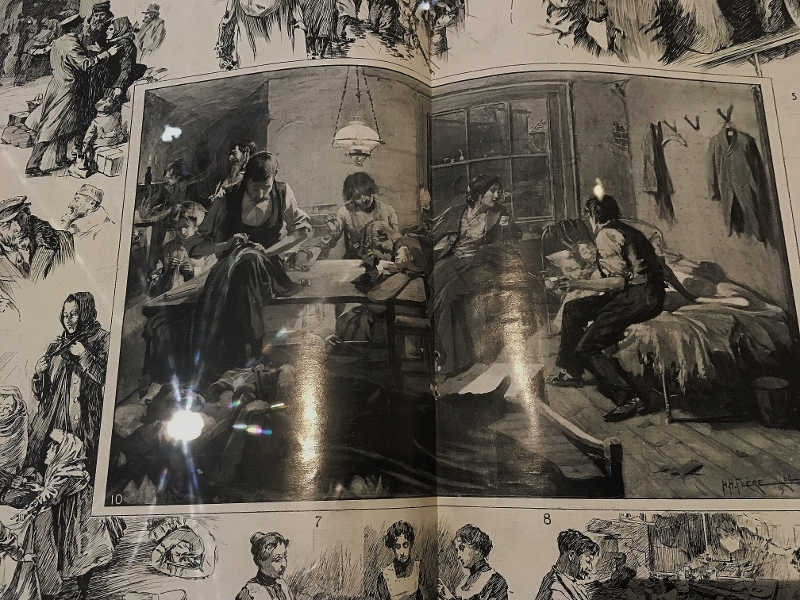

Jewish sweat shop workers and immigrants 1900 London

The Alien Act of 1905 limited immigration with intense xenophobia campaigns, mainly also targeting Jews who were coming from Eastern Europe to escape pogroms.

From a different perspective, the first passenger jet flight in 1952 profoundly altered migration from the tradition of slow journeys on ships (although today we have a sad return to sea travel, and even the most ancient migration, by foot).

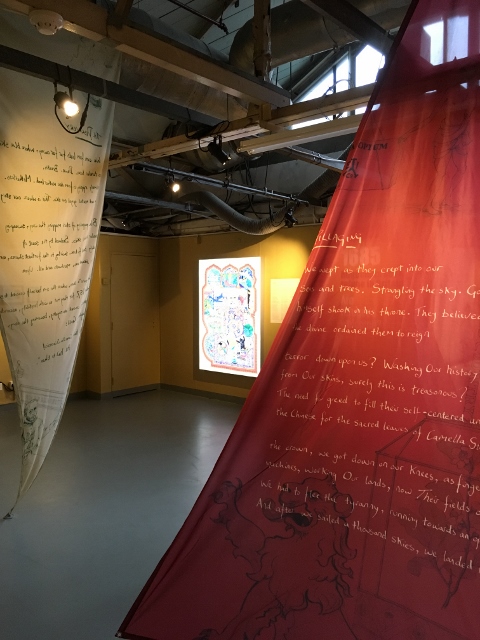

Foreground sculpture by Roman Lokati of refugees from World War II, Basque Country ( his own country) , and Syria. Quotes by refugees on banners

Offering a positive event that pushed back against racism, Rock against Racism in 1978 was a grassroots resistance movement to racism in the music community. It inspires us with its creative means of exposing and countering prejudice.

The last “turning point” 2011, when the “census reveals rise of Mixed-race Britain,” leads us to Brexit. Liz Gerard charted the rising racism in newspapers in the UK month by month leading up to the Brexit vote.

The final segment on mixed race Britain leaves no doubt as to the situation today. Two photographic art projects, Humanae by Angelica Dass, and Mixed by Andrew Barter both celebrate the diversity of contemporary Britain.

What makes the Migration Museum Project exciting though is not only their dynamic and multi dimensional perspective on migration as a process, but their embrace of community.

Mixed by Andrew Barter

Humanae by Angelica Dass

The museum invited these and other contemporary artists to create work pertinent to each turning point as well as organizing workshops, public lectures, and other events. Banners on the ceiling with potent quotations pair with migration stories from the public on small cards against one wall. Children made small ships.

The first “moment “ in the installation, the 1609 founding of the East India Company seems to sail into the gallery with actual sails hanging from the ceiling by Nick Ellwood and Kamal Kaan’s , “And after we’d sailed a thousand skies, “ On each sail handwritten poetry by Kamal Kaan invokes the omnipotence of tea.

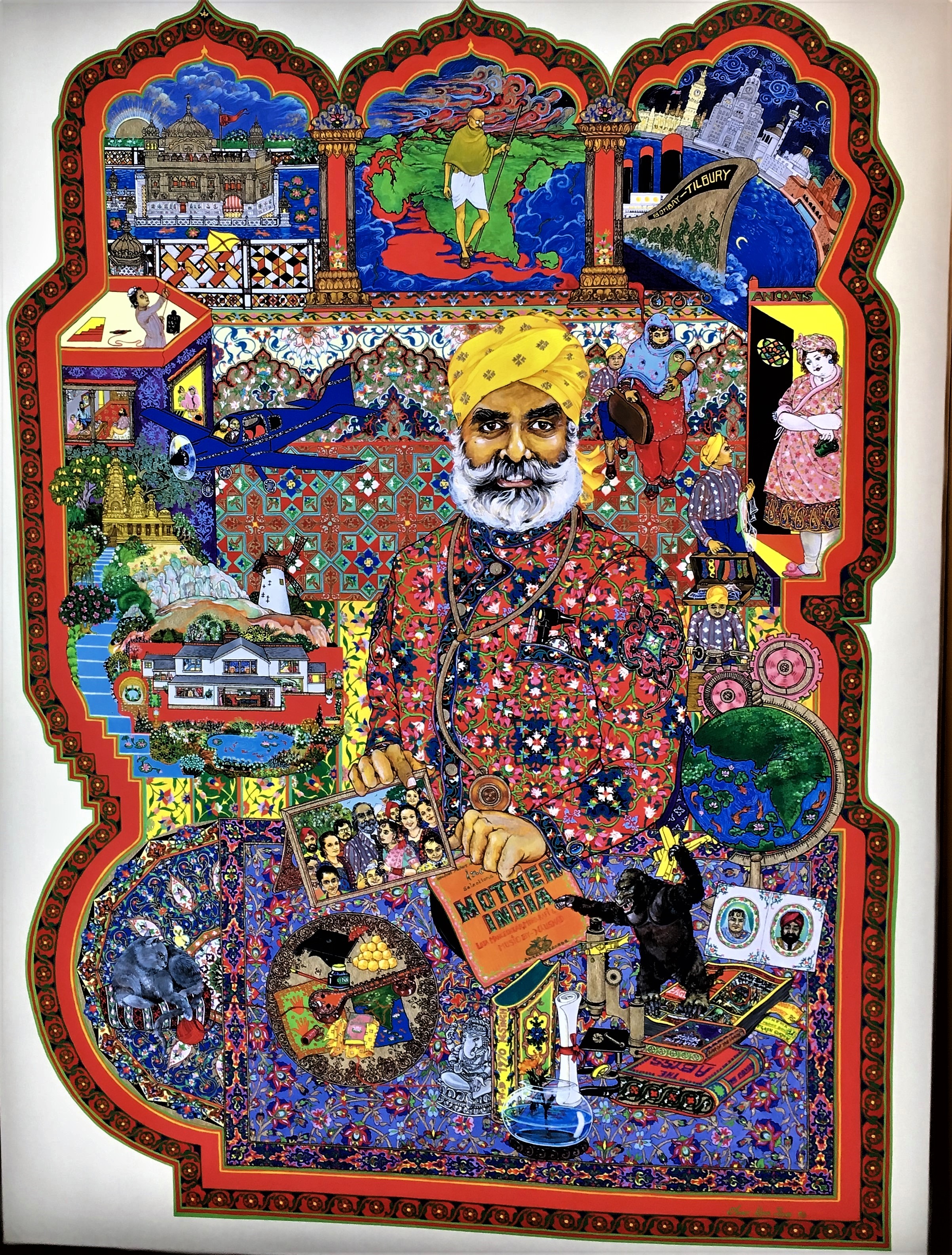

In the same section, and underscoring the complexities of the British Empire’s colonial enterprise with respect to migration, “All that I am,” by the famous Singh Twins features a portrait of their father with their family history of migration in vignettes surrounding him in both traditional and contemporary styles.

The Migration Museum Project have created several exhibitions in temporary venues including “100 images of Migration,” chosen from 100s of photos submitted by the community, “Germans in Britain,” emphasizing an “invisible minority” and “Keepsakes” that invited the community to tell stories about one object that spoke to them of their personal experience of migration. These three exhibitions all took place in community settings, and each venue reached a new audience. Another pioneering exhibition about the Calais refugee camps called “Call Me By Name- Stories from Calais and Beyond” in June 2016, held in Spitalfields, closed the day before the Brexit vote.

Calais, France – November 7th 2015 – People chatting in an Afghan bar and restaurant.

Ph.Giulio Piscitelli

A play called The Jungle, that we saw the night before we left London, was set in the Calais camps in France before they were destroyed in October 2016. Right before that point they held more than 5400 people of whom 445 were children, 335 unaccompanied. But this play was more than set in the camps, we were in the camps ourselves, all seated at tables or on the floor in sections various identified as Iran, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan etc.

The playwrights Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson had created a theater in the camp, The Good Chance Theater, for the refugees to perform and write plays. They have just started another theater in the huge refugee camp outside of Paris.

The actors, by far the most diverse cast I have seen, represented people from the different countries, and they ran around on the tops of the tables and platforms where we sat. Vociferous, desperate, joyfully singing and dancing, tragic, they recounted the building of the camp from nothing, into a city with bars, cafes and a famous Afghan restaurant .

Their dream was to come to the UK, but since they could not, they created a city out of nothing. Then they were destroyed, “for sanitary reasons” and dispersed. The delicate balance of community and conflict has been underscored recently as an outbreak of violence between Afghans and Kurds in a subsequent camp led to the desperate refugees setting it on fire. Today there are many thousand refugees in a holding camp outside Paris. The situation is chaotic and desperate. UK and France are planning to spend millions on a massive barricade in Calais. Why not use that money to enable refugees to find a new home?Many children from the camps are still wandering.

Arabella Dorman Suspended St James Picadilly December 2017

In order to call attention to the plight of refugee children, Arabella Dorman takes the spectacular approach of a giant hanging installation at St. James Church, Picadilly. 700 items of children’s clothes, collected on the island of Lesvos, hang above our heads, a single shoe, an African fabric dress, a shirt, a jacket, pajamas, they seem to fly like angels in the air.

The installation evokes children playing, running, falling, holding hands. I saw it as I listened to a Mozart concert in the church and felt my extreme privilege. Will any of these children ever have the luxury of listening to a Mozart concert or to play one? The installation is intended to remind the UK government of its commitment to take 400 unaccompanied child refugees, a commitment which they have only met by 50 percent.

Ai Wei Wei’s amazing film The Human Flow overwhelms us with its scale, and scope. The filmmaker visited 23 countries over the course of a year. The film combines interviews with migrants that covers many topics from the wretched conditions in the camp in Northern Greece where thousands are stuck unable to go on to Macedonia, to the airport in Berlin where small compartments house hundreds of refugees, who are isolated from society and “bored” as one young girl states.

The people interviewed always spoke on their own without interviewers or a question, but Ai Wei Wei appeared throughout the film in various capacities, helping refugees off a boat, getting his head shaved, talking to border guards on the US border. The only actual scene of the drivers of migration was a scene of bombing near the end, but the devastation spoke loudly of ruined homes and communities.

The EU crisis has its roots in the destruction of war and climate change both driven by the developed world, and particularly imperialism. It is responsible for these refugees. Who would leave their home unless they felt they could no longer live there. To take the perspective that these desperate people must be detained or deported is a betrayal of the basic principles of humanity.

This entry was posted on January 16, 2018 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, Migration, Uncategorized.

Prisons and Detentions: A Perspective from the UK

Part I The Darks

Before the stylish Tate Britain, the Millbank prison rose forbiddingly on the same site from 1816 to 1890. In an extraordinary audio guide, The Darks Ruth Ewan and Astrid Johnston take us around the original prison, the utopian principles behind it and the realities of the grim conditions inside it .

.

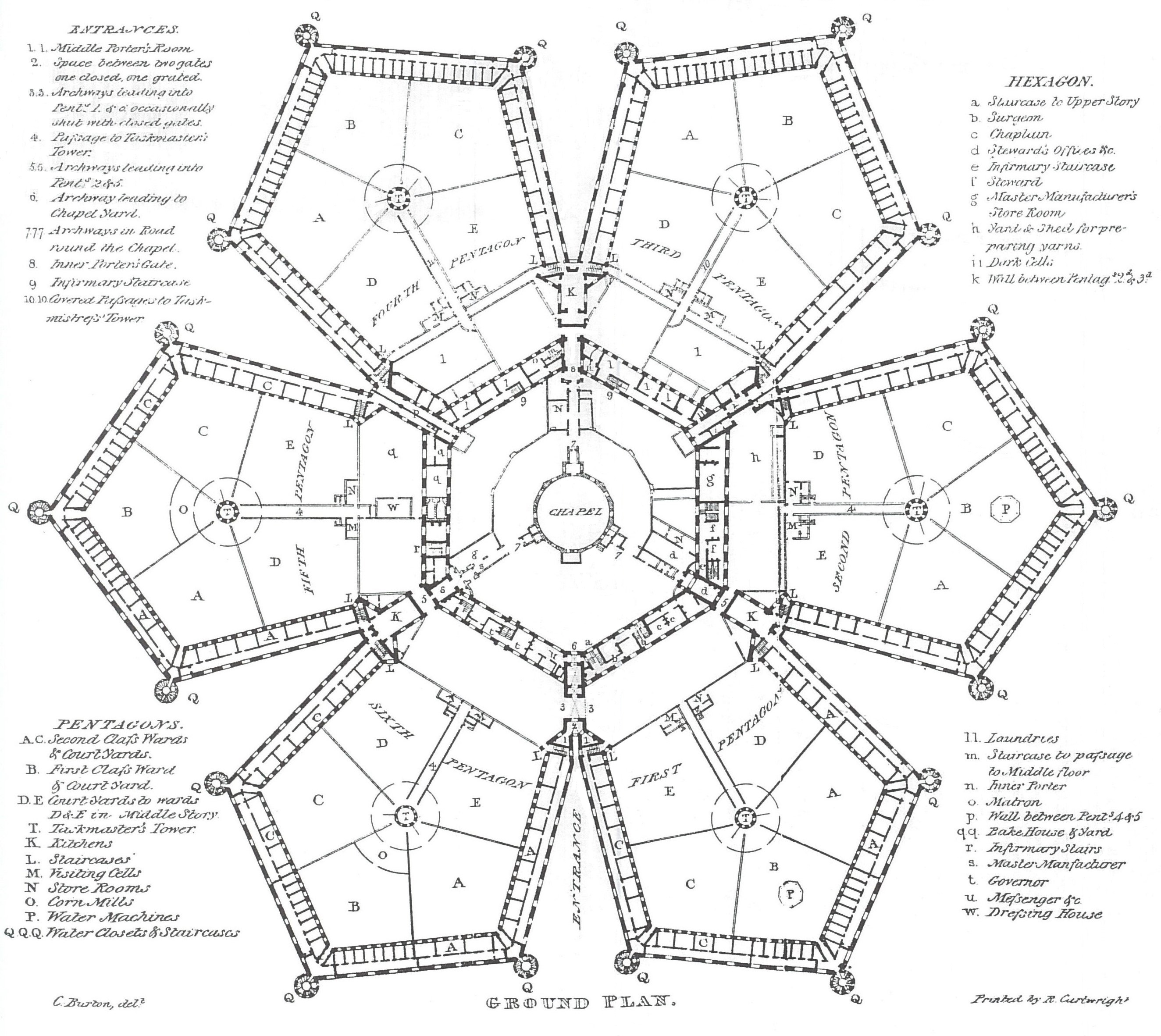

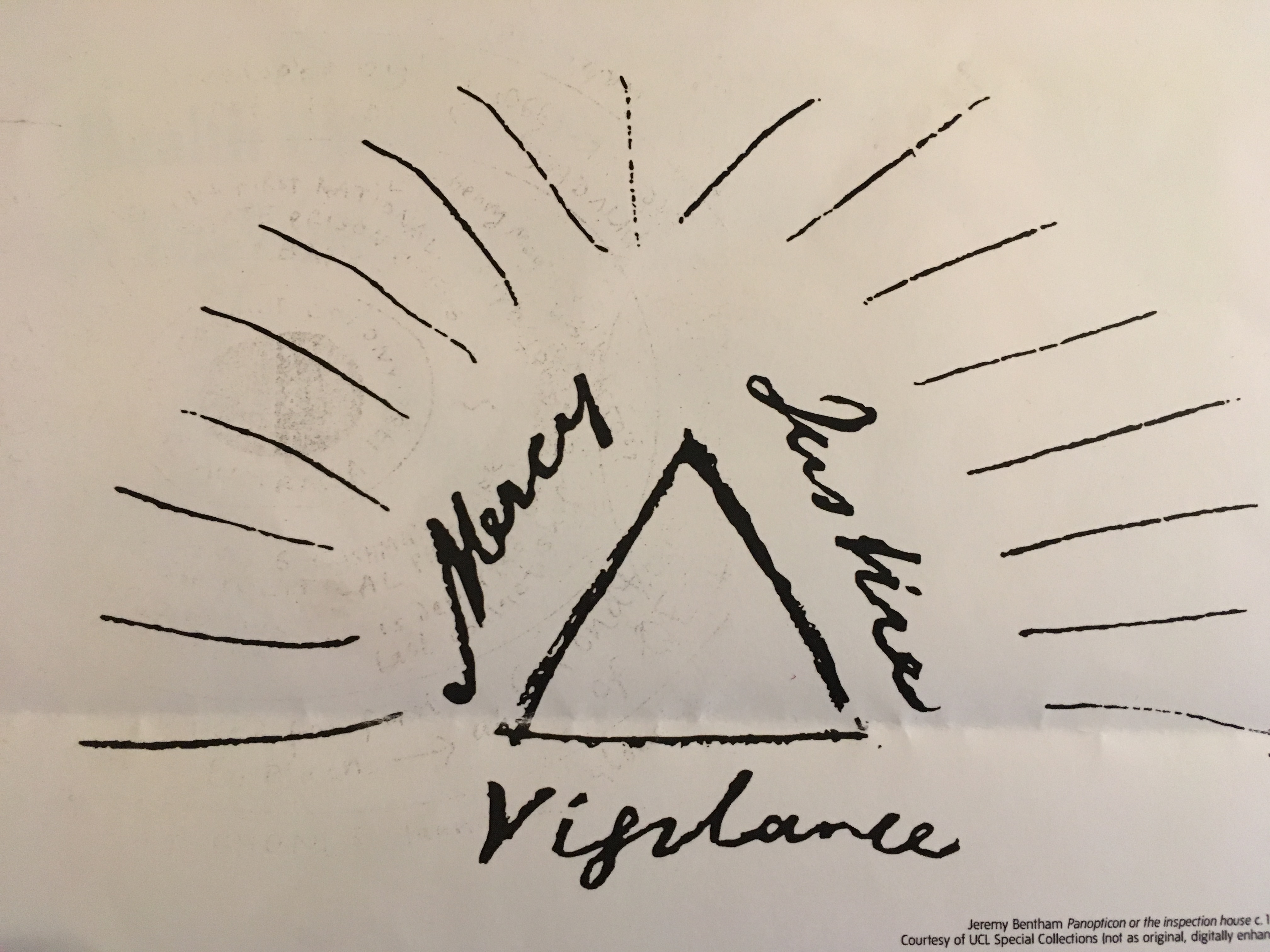

Jeremy Benthem Panoptican or the Inspection house c 1787

First we hear of the idea of two prisons, one real, one imaginary. The imaginary prison was the idea of Jeremy Benthem who imagined the panoptican, a single inspector able to see everyone at once, but the prison was meant to be iron and glass, and an improvement over existing prisons. Benthem’s vision of surveillance has of course survived and today we go way beyond his idea of the visible eye, to unseen surveillance everywhere.

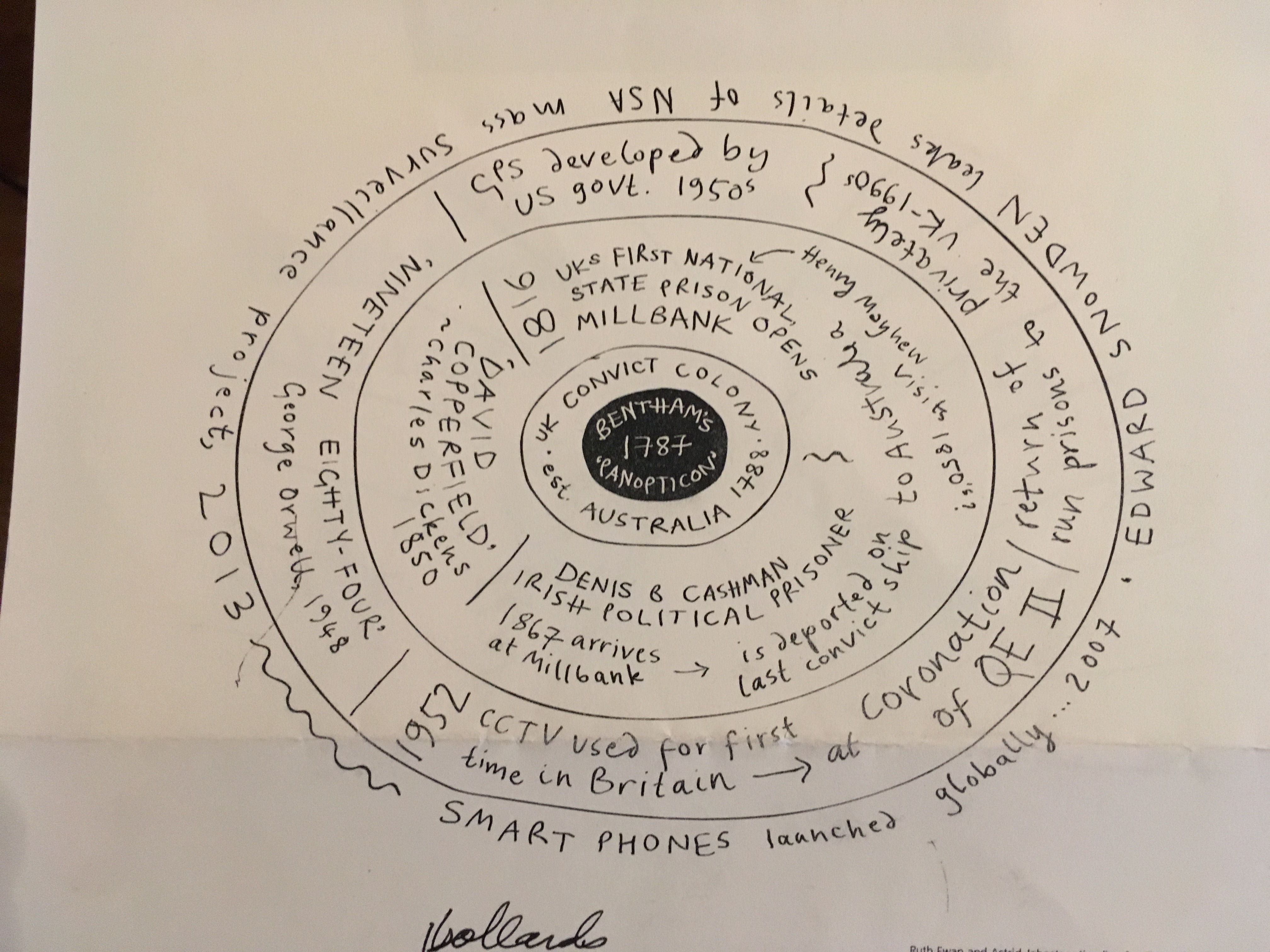

The tour is accompanied by a chart of concentric circles that lead from Benthem’s 1784 panoptican vision to surveillance by smart phones.

On the tour we see the few remnants of the original prison such as this bollard, and a “moat”.

Originally marked the steps where prisoners boarded boats to be transported to Australia

We hear the voices of prisoners and learn of the horrendous conditions inside. Well known authors such as Charles Dickens in BLeak House described the prison. Henry James in The Princess Casamassima describes the gruesome infirmary.

The Darks is a reference to the darkness of the punishment at the lower level. It is the antithesis of Benthem’s idea of a transparent structure of glass that would reform people through the power of reason. Instead a turreted labyrinth was built inside and an octagonal wall with 16 acres of grounds.

The land originally was a burial ground for plague victims, purchased by Benthem to build the prison at a time when prisoners were held on decrepit ships on the Thames for transport. In the late 18th century colonies were in revolt and the US closed its borders to prisoners, so the first holding penitentiary in the UK was completed in 1816. The prisoners were supposed to be deported to Australia, but many remained there in miserable conditions, or died there.

Today we have the elegant Tate Britain whose central interior space still echoes the panoptican .

Part II Detention Centers in UK today

Brook House Tinsley House/ Immigration Removal Center, Perimeter Road South, Gatwick Airport, West Sussex, England copyright Rob Stothard

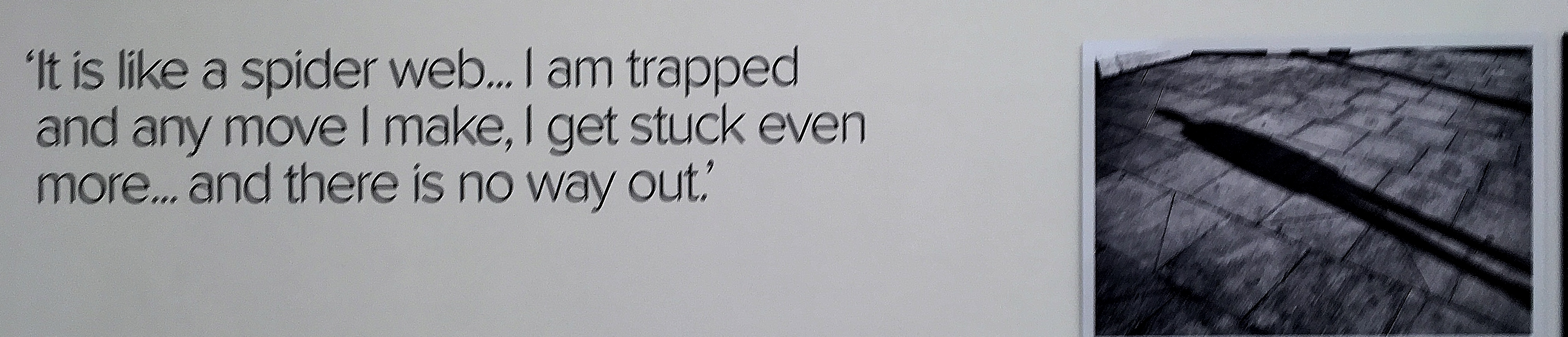

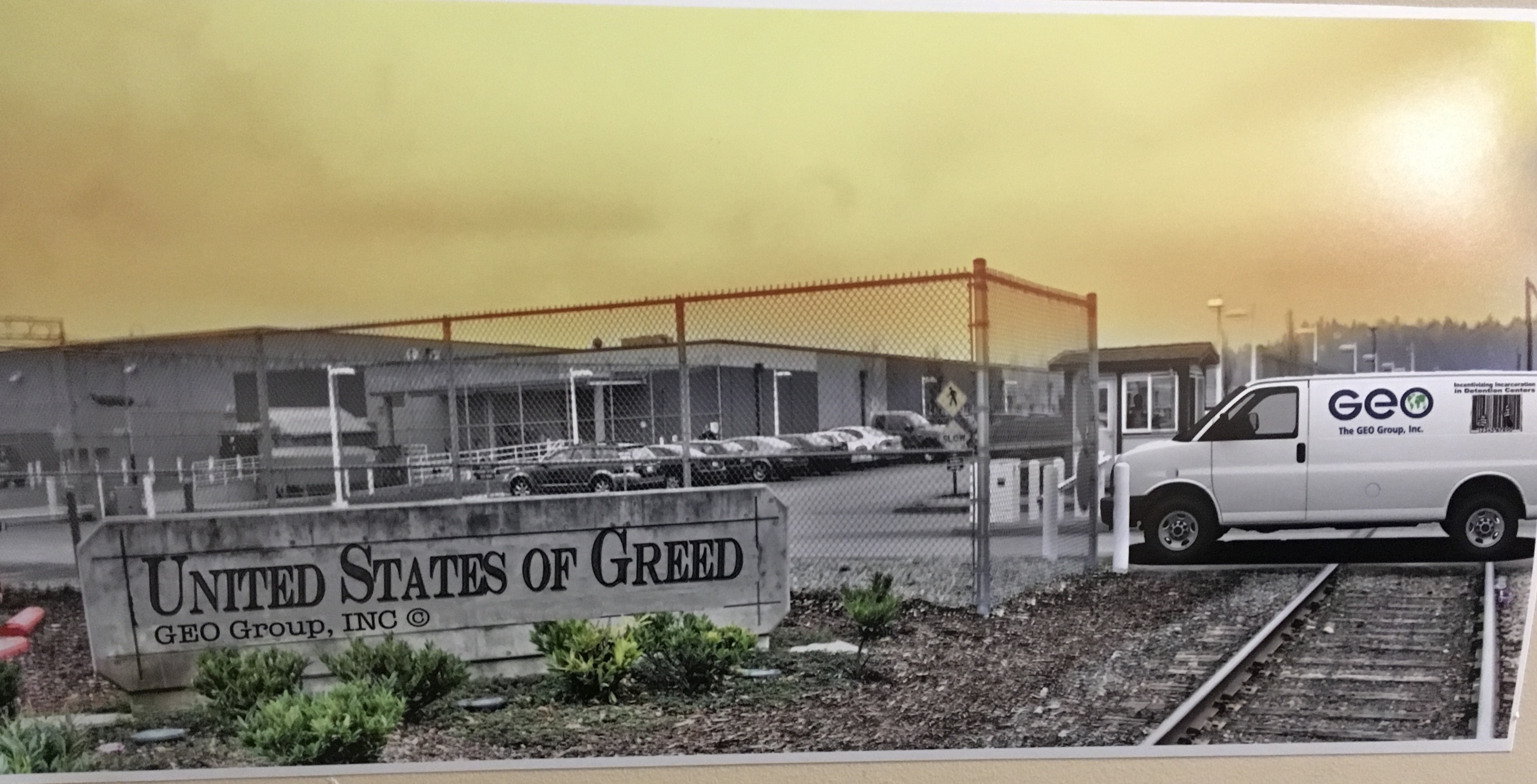

The practice of detention continues in the UK. In much smaller numbers than in the US, it is nonetheless equally inhumane, run by the same corporation, GEO, that runs US detention centers. Rob Stothard and Silvia Mollicchi have written Removal, A Short Guide to the United Kingdom’s Immigration Detention Estate.They photograph only the outside of “holding facilities” “short term holding facilities- Reporting Centre”(4), “pre departure accommodation” (1)and “immigration removal centers” (7)

The photographs give us innocuous country lanes, fences, office parks, and houses. The anonymity of the sites is intentional, and the artists did not enter them or photograph any people, although each site is accompanied by a detailed description and often the frequently tragic story of a particular detainee. We have been reading frequently in the Guardian about people who have lived here for fifty years who are being rounded up and deported. These people came at a time when papers were not required, as part of the Commonwealth.

Now they are grandparents and shocked to be sent off to detention and often back to a country they don’t even remember.

In another approach to detention, Greg Constantine photographs “stateless people” around the world, in the exhibition I saw “Nowhere People,” sponsored by the UNHCR, he focuses on people in permanent detention in the UK. They cannot go back to where they came from and they cannot stay in the UK. There are 10 million people around the world who live without a nationality, over 75 percent are from minorities such as the Royingya, the largest stateless group.

In the UK they are in permanent detention.

Nana Varveropoulou in collaboration with detainees 2014

Nana Varveropoulou succeeded in getting inside a detention center at Colnbrook from 2012 – 2014 to do a workshop. That led to collaborating with detainees on a photographic project documenting their lives called No Mans Land. You can see her account of it in the article from the Guardian, as well as the images on her website.

These artists make the invisible visible. They refuse to let a human tragedy be swept aside in the midst of the endless focus in British news on Brexit.

Anniversary of Russian Revolution Part III: Pussy Riot

“Inside Pussy Riot” at the Saatchi Gallery was part of an exhibition called “Art Riot: Post Soviet Actionism.” The larger exhibition had a good deal of artwork/actions some of which were inspired by Pussy Riot’s example.

The Saatchi Gallery is large and grand, on the Duke of York Square which is a fashionable part of London. The fee for the performance called “Inside Pussy Riot” was 21 pounds, but we didn’t need to pay it because I am an art critic, but I kept thinking about how expensive it was!

The Guardian art critic. Charlotte Richardson Andrews called out the huge contradiction of revolutionary resistance inside such an upper crust space. Richardson in contrast celebrated the performance “Riot Days” by Maria Alychokhina, a one time event, at the Islington Town Hall. Alychokhina has also written a well received book called Riot Days. ( January 12: I just finished reading it and I can’t recommend it highly enough. The performance described below is intended to make us experience some of Maria and Nadia’s experiences in prison. Maria is a really impressive person, pursued resistance on behalf of the prisoners inside the prison, often at the expense of hostility from other prisoners who were punished on her behalf, and the guards as well, whom she called out, and won a case against their abuse. She held repeated hunger strikes in order to win better conditions for the women in the prisons where she was detained, she was released as part of an Olympic Amnesty by Putin in 2014)

Although I wasn’t expecting much of “Inside Pussy Riot,” I was surprised. I decided it was in fact a radical intervention in the Saatchi space, not a sell out. It intended to expose the abuses of the Russian prison system as the two Pussy Riot members who were jailed experience it. It was not simply about defying Putin, it was about oppression and injustice.

I was not allowed to take pictures so I will simply describe what happened.

The performance was put on by a theatrical group called Les Enfants Terribles in collaboration with the Tsukanov Family Foundation, a charity “which supports education of talended children from the Former Soviet Union countries. ” The actors were doing continuous performances with a new group of people coming through every 15 minutes, so it was extremely demanding for them. Hopefully the entry fee gave them appropriate compensation.

The performance put us inside the Russian penal system. The back story, which is familiar to most of us, is that the punk band invaded Cathedral of Our Savior Church in Moscow with a 40 second performance “Punk Prayer,””Mother of God Drive Away Putin ” in 2012 as a protest against Putin and his exploitation of religion, the misogyny of the church and the oppressive power of the state paired with religion.

(There is a film of the performance and arrests). 3 were arrested, 2 served a sentence, accused of Hooligansim. Pussy Riot had done other public interventions in Moscow and elsewhere protesting the state, but their arrest actually made them famous.

It also ended their position as carnivalesque protestors. Their balaclava masks were stripped off. Their identity as a collective of anonymous superheroes forever evaporated. The incarceration in the Russian penal system changed the two women into activists of a different type, activists for justice particularly for incarcerated women. It was the experience of the penal system that the performance re-created.

So the first room we entered was a church environment, with an altar with among others, Putin and Trump, and pillars underneath reading “poverty” and “pollution.” Other “stained glass windows” featured nuclear mushroom clouds. The design of the altar was actually similar to that of the cathedral where they had protested.

A priest was ranting at us about the sins of women.

We were given balaclava hoods in different colors with eye and mouth holes and placards with phrases like ” Wealth Does Not Define Success” “Imagination is not the Enemy” Dreaming is not Permitted” “Ask Nothing, Demand Nothing.” We held them up to a camera and protested.

In the next room, one person was asked to take off all their clothes. She refused, then reluctantly began to comply. When she got down to her underwear, she said she was one of the actors, but in the prison she would not have been able to refuse.

All of the aggressive officers (Enfants Terribles) who told us what to do were mean and rude.

The spaces got getting smaller and smaller. We entered a cell. On the other side of the wall of the cell was a judge placed up high in a “throne” that had a giant face subtly outlined on it, to one side was a large dog, to the other a shadow puppet on a pole. The phone rang, the judge answered, then she said in analyzing the evidence, she found us guilty. ( This part of the performance had an eerie and dreadful resemblance to the bail hearing I went to at the Northwest Detention Center for Pavel Bahmatov, who was included in the summarily analyzing the evidence he was promptly denied bail)

Then we noticed the judge was a puppet also, hanging on chains from the ceiling.

Next we went into a room in which we were instructed on how to behave in a penal colony – no physical contact, no eye contact; we removed the balaclavas and put on jump suits. We were told that all we could do was stare ahead as we were put at work tables, where we were asked to pursue a mindless task ( mine was cleaning coins with a toothbrush).

We went on to a room with a latrine, a disgusting space in which we were told of tortures done there for those who disobeyed.

We had “exercise”, forced movement, robot like.

Then last, ( worst, I was amazed I survived all this), solitary confinement in a dark room. While there we heard a recording that was a call to arms, to resist the system, and we were given another protest placard. when we came out we protested again with the placards.( that was a weak part of the event)

So it was immersive. It was intended to give us a sense of the coercion and pettiness, the intentional forced acts that limited us in every way.

It was a relief to get out of there!

The cyber feminist Russian writer/philosopher Alla Mitrofanova writes about Pussy Riot in the context of the history of feminism in Russia in the twentieth century. Russian feminism is originally embedded in the Russian Revolution, when abolishing marriage and the family and enabling all children to be raised collectively, while women worked was a radical idea for restructuring the position of women in society. “Feminist politics aimed to destroy the triple oppression of women: the patriarchal, the bourgeois and sexual in one shot.”

During the Stalin years, the family was brought back, so women were required to work and also do the work of the bourgeois household. Feminism returned only in the early 2000s in various forms, some more political, some more bourgeois.

According to Mitrofanova, Pussy Riot is a radical “reset of the political statement on the part of resistance .” ( ” The Public and the Political in Feminist Statements: Street Actions in St. Petersburg and the Pussy Riot Case,” n.paradoxa. vol 27 Jan 2011. ) . But she is also somewhat ambivalent referring to their “symbolic antagonism.”

My feeling is that any disruption is a positive, and even if they are currently on the road promoting their actions as a type of symbol of resistance, they still are activists, both within the context of the society in general as disruptive women, and in the context of the very passive smug and capitalistic art world. Their immersive performance definitely affected me more directly than any of the work on the walls of the Saatchi gallery. It actually accurately suggested the injustice and oppressions of justice systems.

If you are neutral in situations of injustice you have chosen the side of the oppressor Desmond Tutu

Image at the exit of “Inside Pussy Riot”

This entry was posted on December 15, 2017 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, Feminism, Russian Performance Art, Uncategorized.

Anniversary of Russian Revolution Part II: Dostoevsky’s Demons in London

“Nothing and ever was more unbearable for a man and a society than freedom,” Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky’s play “Demons” ( also known as the Possessed) put on in the atmospheric old church , St Leonards, in Spitalfields by the Split Moon Theater company also joined in the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution in London.

It is referred to as Dostoevky’s “prophetic vision of the Russian Revolution and the bloodshed that followed ( which we saw ample evidence of at the Tate Modern exhibition see previous post) .

“The Demons” is based on a murder in 1869 of a student Ivanov by his co-conspirators and the subsequent trial. The satirical play is set in a provincial town with a cell of conspirators testing radical ideas, at that time, of nihilism. We had bizarre jumps from political speeches, to mad murmurings of a demented wife, to a bourgeois matchmaking and a love affair all centering around a “gentleman” of the town, Nikolai Stavrogin, who is also drawn into the conspiracy.

I found this explanation online, but could not find who wrote it:

” I realized that the characters weren’t the demons. They were the possessed. The demons that possessed them weren’t little red men with horns and goatees. They were much more terrible. Some of the minor demons: ignorance, vanity, conceit, lust, and indifference. The real bad asses though, were ideas like atheism, socialism and nihilism.These ideas consumed and blinded normal human beings such that they acted evilly.”

You can read the whole novel here, even just dipping in gives you a sense of the brilliant satire.

Here is a description of one of the conspirators who was eventually murdered in the play. It gives the flavor of Dostoevsky’s sardonic views on politics:

“Shatov had radically changed some of his former socialistic convictions abroad and had rushed to the opposite extreme. He was one of those idealistic beings common in Russia, who are suddenly struck by some overmastering idea which seems, as it were, to crush them at once, and sometimes forever. They are never equal to coping with it, but put passionate faith in it, and their whole life passes afterwards, as it were, in the last agonies under the weight of the stone that has fallen upon them and half crushed them.”

What was thrilling about the production was that we went from one space to another in the theater. ( At night it appeared considerably more atmospheric, crumbling, and even frightening). We started seated in the nave, then went up stairs to a second room, one part was staged on the balcony opposite us. We followed the cast around from one space to another.

Also included dance, avant-garde off beat lighting and events, Dada really.

Albert Camus admired this play enormously and restaged it in the 1950s.

The church itself is a site that dates back to the Romans and even earlier as a sacred site. Then there was an Anglo Saxon church replaced by the Normans. (We encountered this sequence over and over in England)

St Leonard is a patron saint of prisoners and the mentally ill. In Tudor times a Theater was build nearby and Shoreditch became the first English theater district.

Shakepeare premiered some of his early plays here

Here is a trailer that evokes the eeriness of the performance.

This entry was posted on December 10, 2017 and is filed under Russian Revolution, Uncategorized.

“Red Star Over Russia”

Art and Politics are everywhere in London at the moment. Whether it is the Imperial War Museum’s Art of Terror, the Migration Museum, an entire wing devoted to Art and Society at the Tate Modern, Red Star Over Russia at the Tate Modern, or the audio tour “The Darks” describing the former prison at the site of the Tate Britain, there has never been a time when socially engaged art was more prominent here

And that doesn’t even count the events in honor of the anniversary of the Russian Revolution such as Pussy Riot’s immersive evocation of the prison system in Russia or the play by Dostoevsky The Demons (The Possessed), creatively performed in a crumbling church in Spitalfields.by Split Moon Theater. In addition, there are references to Brexit in the play Albion by Mike Bartlett and the troubles in Northern Ireland in Jeb Butterworth’s play,The Ferryman.

Whew. Where to begin. I am fortunately spending nine weeks in London and feeling quite overwhelmed with so much to write about. I have submitted two articles for publication on the Imperial War Museum exhibition and the Migration Museum, so I will return to them in a separate post

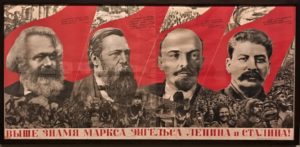

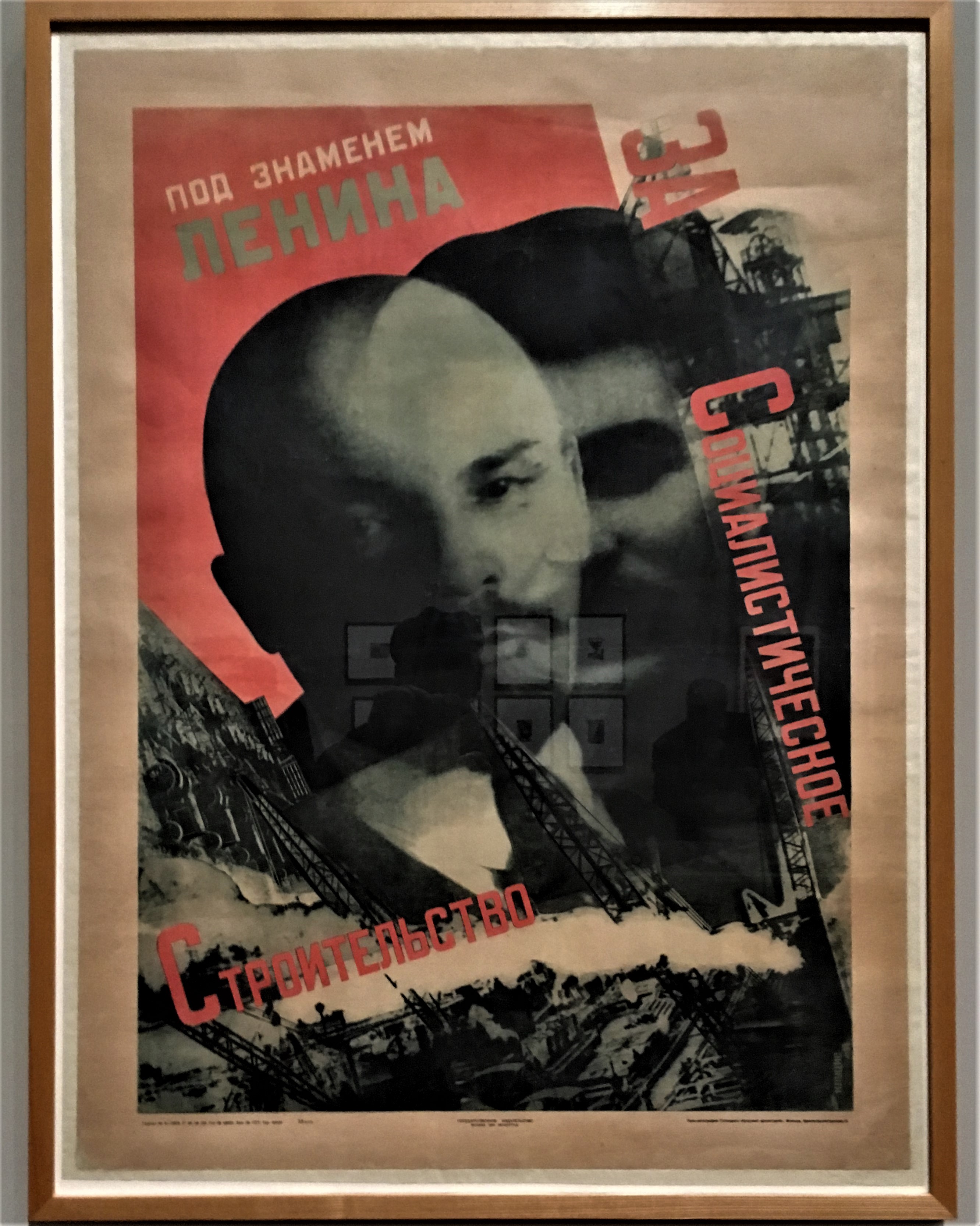

In honor of the100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, the extraordinary collection of David King is on display at the Tate Modern in “Red Star Over Russia.” It includes the history of the Russian Revolution from the last days of the Tsar to the death of Stalin. The variety of visual materials stunned me, ranging from postcards, journals, banners, and informal photographs to the famous fotomontage designs of the late 1920s. Altered photographs have heads cut out as they are declared “enemies of the state.” This is only a small selection of King’s collection of doctored photographs ( or of his collection as a whole) , first published in 1999 as The Commissar Vanishes. Grim mugshots of people, ranging from Lenin’s associates to peasants, who were executed in Stalin’s purges in the late 1930s fill the center of one gallery, together with each of their biographies. On loan were some of the huge paintings sanctioned by Stalin in the socialist realist style.

The historical trajectory of the exhibition starts in the end of the tsarist era passes through the 1905 revolution, World War I and the Bolsheviks in 1917 to the oppressions and murders of the late 1930s through the nightmare of World War II when posters endeavored to create nationalistic fervor as the Nazis invaded ( and after Stalin had executed 25,000 high ranking officers between 1937-41)). It ends with the post war era of continued nationalism until Stalin’s death in 1953: we see him lying on his deathbed.

The moments of change appear vividly in the arts displayed. We could see the photographs of the earliest revolutionary sculpture that did not survive, because it was made in plaster, giant sculptures in public places, then the thrilling development of a new vocabulary for a new society in photography, design, film, painting, printmaking and all other media.

One room included a few of the now well known visual artist partnerships of that era: Valentina Kulagna and Gustav Klutsis, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Vavara Stephanova, El Lissitsky and Sophie Lissitzky-Kuppers. The last two pairs designed photomontage displays and magazines throughout the 1930s.

Gustav Klutsis was executed, but many visual artists survived, although disillusioned and compromised. We saw angled abstractions and upright realism by the same artists juxtaposed on a single wall.

Musicians such as Dimitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokovie also survived the purges with careful accomodations. Shostakovich was attacked for being too avant-garde, but managed to create his fifth symphony as a sop to Stalin, with more traditional musical reference points. (I was fortunate to hear this symphony the same day I went to the exhibition. The drums were regular, loud and repeated, they could be a parody, a warning, or a military march. Mahler’s soothing rhythms dominated one whole movement; Bach and Beethoven as well as Handel permeate).

David King’s life long obsession as a collector was to rescue Trotsky from visual oblivion. Stalin had not only exiled him and had him assassinated, he obliterated his face from every photograph and destroyed his books throughout the USSR ( event today he is not acknowleged). King resurrected him through his personal sixteen year search for images of Trotsky. He wrote a photographic biography of him in 1986. Three black and white film clips in “Red Star” gave us Trotsky at meetings giving speeches, bringing him back from visual obliteration in the story of the revolution inside the Soviet Union.

But of course Trotsky’s ideas have lived on continuously outside the USSR, in the books he published such as Literature and Revolution, 1925. In the late 1930s as Stalin systematically executed the founding fathers of the Bolshevik revolution, as well as hundreds of thousands of others, far away in the US Trotsky became the alternative to Stalinism for some members of the Left. His memorable positioning of art, culture and intellectuals in general as the vanguard of Revolution is certainly the heritage of the early days of the Bolsheviks and the 1920s when artists were spreading the ideas of the Revolution across the massive USSR.

In the exhibition we see the vanguard of culture from the earliest monuments erected to Lenin and Marx, the agit prop trains, the banners from the far East encouraging the new society, the posters calling on Muslim women to uncover themselves, and much more. The sweep of the material is dazzling and at the same time intimate. We see rare photographs of Stalin’s wife (who committed suicide), we experience the exuberance of the artists, we witness the nightmare of the purges. Above all, we think about the terror of an insane leader with too much power.

The emotional roller coaster of the exhibition echoes the joys and horrors of the USSR itself in the 20th century.

This entry was posted on and is filed under Uncategorized.

Hanaa Malallah Part II 2017 Ten Years Later and Thirty Years Ago

I met Hanaa Malallah in 2007, just after she left Iraq under duress. At that time I wrote a long blog post about her work which I link here.

Here I am in London again, ten years later, and, very fortunately, Hanaa is having a solo show. She is currently based in Bahrain as an associate Professor of Art at the Royal University for Women there.

She is teaching art and theory. Hanaa has a Ph.D. in the Philosophy of Painting with a thesis on “Logic Order in Ancient Mesopotamian Painting. ” ( I remember visiting the British Museum with her in 2007 as she explained the meaning of the Royal Game of Ur to me.)

While a young artist and professor in Iraq she stayed in the country through the Iran/Iraq war ( 1980-1988) and the Gulf War ( 1990 91). She also stayed during the period of severe sanctions during the 1990s, when she was unable to travel, and supplies were limited in every way. During that time she immersed herself in historical Mesopotamian art as a crucial reference point in her work.

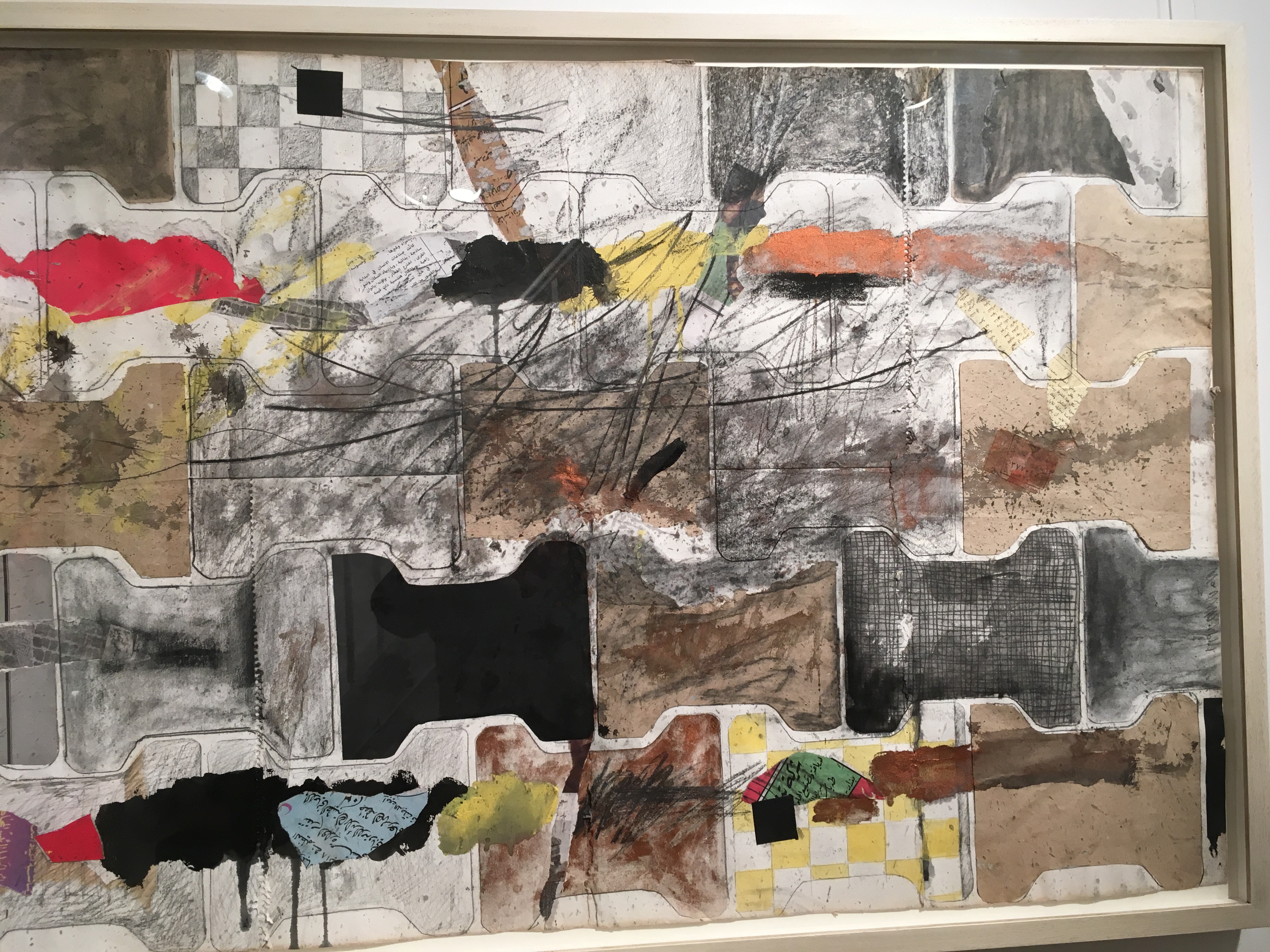

The present exhibition “From Figuration to Abstraction” at the Park Gallery in London is both fascinating and unexpected. A friend of hers in Baghdad sent a selection of her work from primarily the 1990s to London. So the current display includes those works.

As we stood in front of them, she said that each one represented a major show that she had in Baghdad . Many works were looted from her home in Baghdad after she fled the country. Her work also hung in the Modern Art Museum in Baghdad, which was looted. A team of artists and curators have recovered some of those hundreds of works in street markets, but many hundreds are gone, and the museum itself is now a shadow of its former self. Many of the works are in storage, and the museum has no funding. Only 200 works are on display out of the original collection of 8000, 7000 of which were looted.

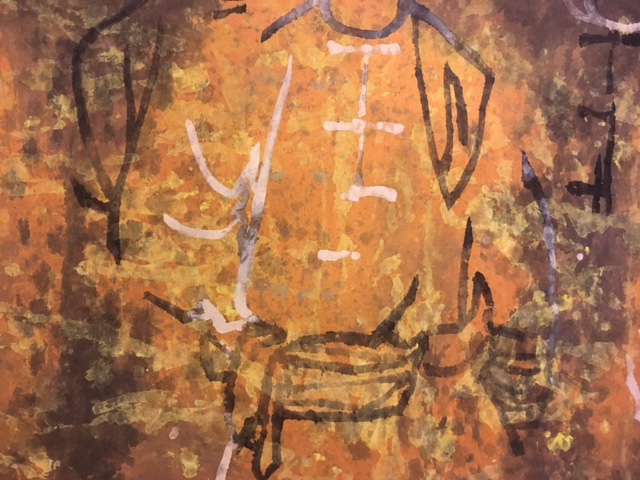

So we have four  early self-portraits. Here is one of them from 1989 that reveals an intelligent and probing and perhaps tragic person.

early self-portraits. Here is one of them from 1989 that reveals an intelligent and probing and perhaps tragic person.

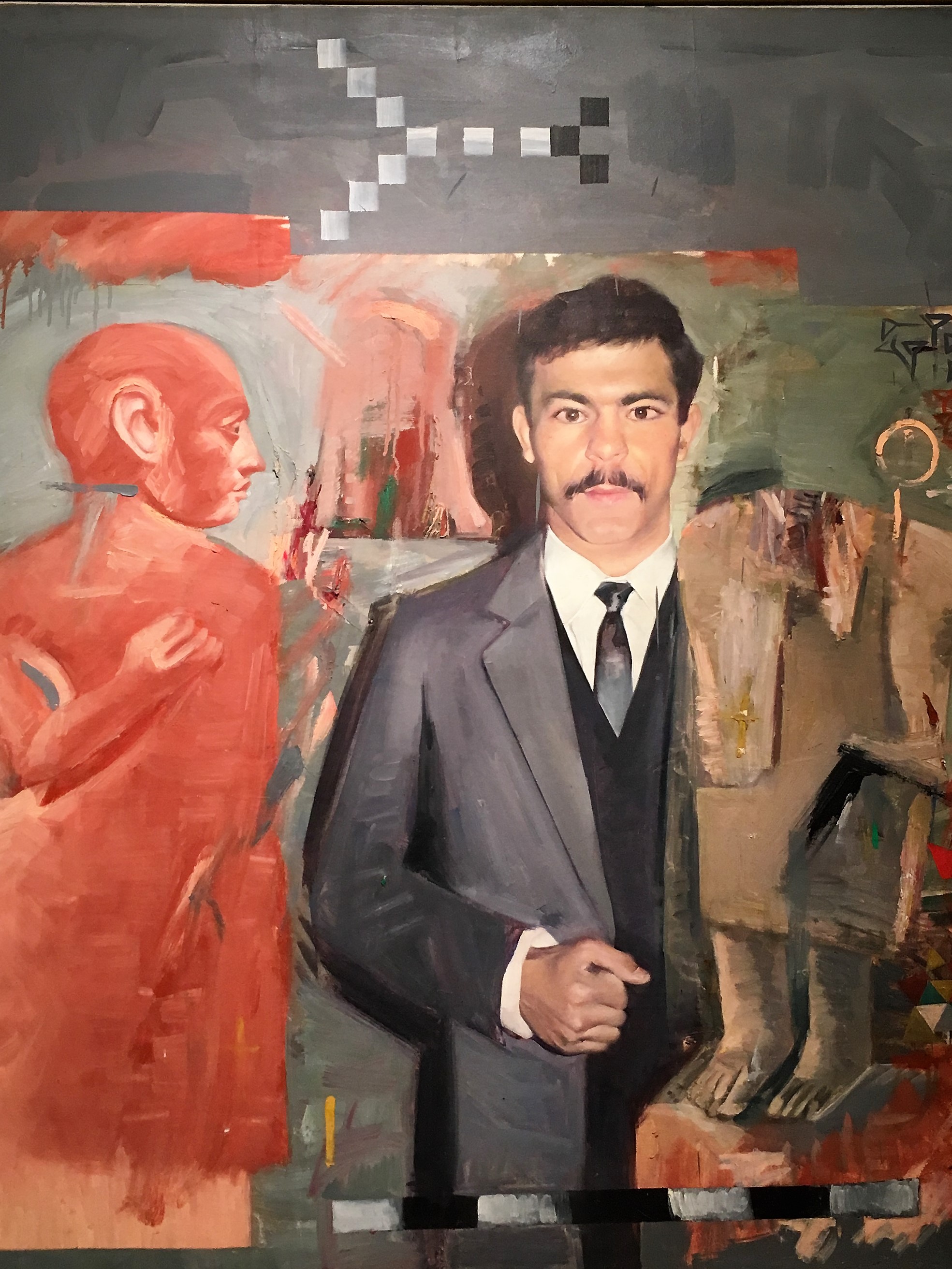

The next fascinating surprise is the 1991 painting called The Guard.

A face with piercing eyes looks directly at us: he is a museum guard at the National Museum of Iraq. He is shown between two mesopotamian sculptures, one seems to look at him, as though the artist is suggesting a direct communication between the ancient stone statue and the contemporary Iraqi.

Half lost under abstract brushwork is a second statue, a seated figure, perhaps Gudea of Lagash. I am giving you details of the lower right hand corner of the painting as it descends into increasingly complex abstraction and brushwork

Keep in mind that this is the same museum that was looted at the time of the 2001 invasion of Iraq.

In this single painting we start to see the artist’s connection to the history of Mesopotamian art as well as her stunning technical facility.

Sketch of Alwarkaa Wall Temple Artwork 1991 also pays homage to a hugely important site, also known as Uruk in Mesopotamia.

We see in the detail meticulous geometry interrupted by a scarred surface. We all remember the horrendous pillaging of the National Museum during the ignorant American occupation of Baghdad. In 2006 a report recorded that 10,000 objects were still missing. We know that the dysfunctional Iraqi state is not protecting its ancient sites.

Donny George, the heroic director of the National Museum, himself had to flee at the same time that Hanaa left in 2006. He personally managed to recover almost half of the antiquities stolen during the disastrous American invasion. He died of a heart attack at age 60 in Toronto Canada. I was fortunate to hear him speak at the College Art Association as well as to meet him at an exhibition of Iraqi art in New York City.

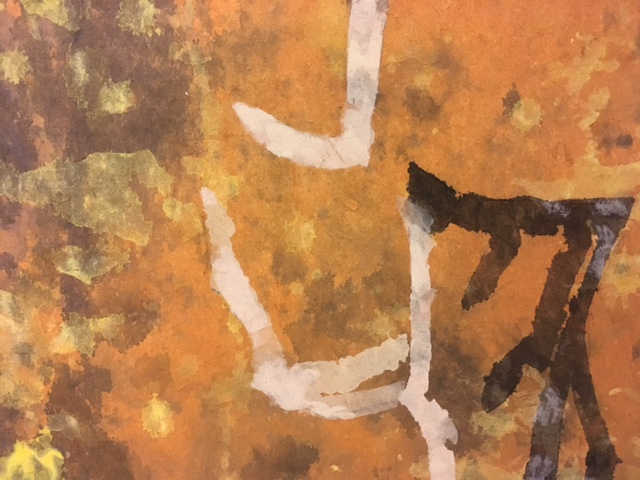

Other works by Hanaa are works from the 1990s that emphasize pattern. This is an example from 1993 and a detail where we again see the way in which the regular pattern is interrupted by the black dripping form in the upper left. The geometry is based on ancient symbolism, the black shapes look like an invasion.

are works from the 1990s that emphasize pattern. This is an example from 1993 and a detail where we again see the way in which the regular pattern is interrupted by the black dripping form in the upper left. The geometry is based on ancient symbolism, the black shapes look like an invasion.

Here is a detail of another of these pattern works that from 1999

And 2002, not long after the war started and the museum was looted. We experience both her deep commitment to the historical symbolism of Mesopotamian art and her sense of tragic loss as her homeland and its art is destroyed.

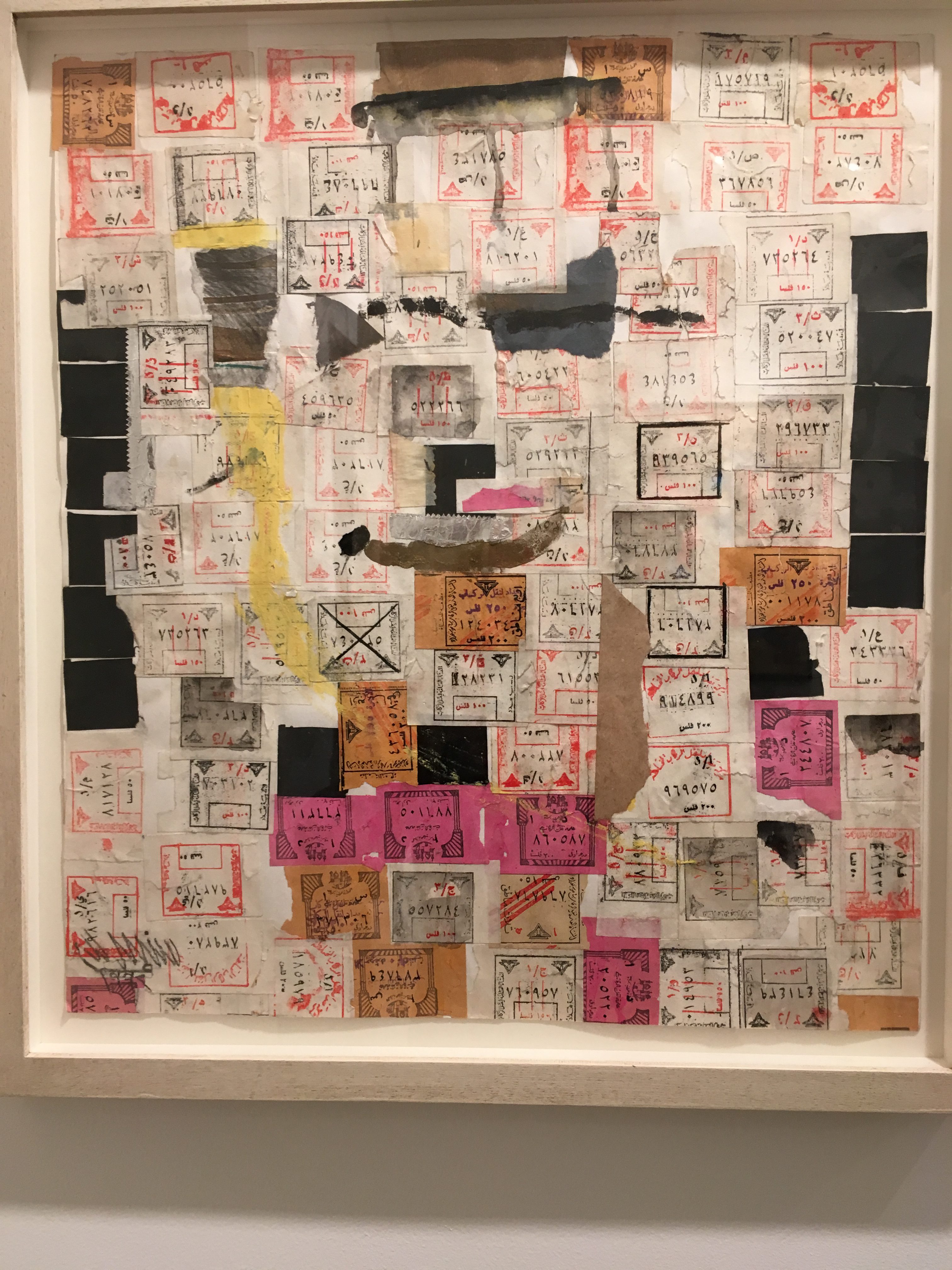

In addition there are several paintings from the 1990s that reflect the result of sanctions on Iraq’s artists. One 1993 work is composed of bus tickets,

another scraps from the street.

Many other types of work appear in the show, showing Hanaa’s willingness to experiment, meticulous pencil marks that suggest counting, colored squares , patterned works based on ancient references.

For me, The Dawn, 1995 was the most dramatic. Smaller than many of the other works, we see a series of carefully constructed compartments made from canvas, overlaid with energetic black and white paint strokes that suggest violence. This is a detail.

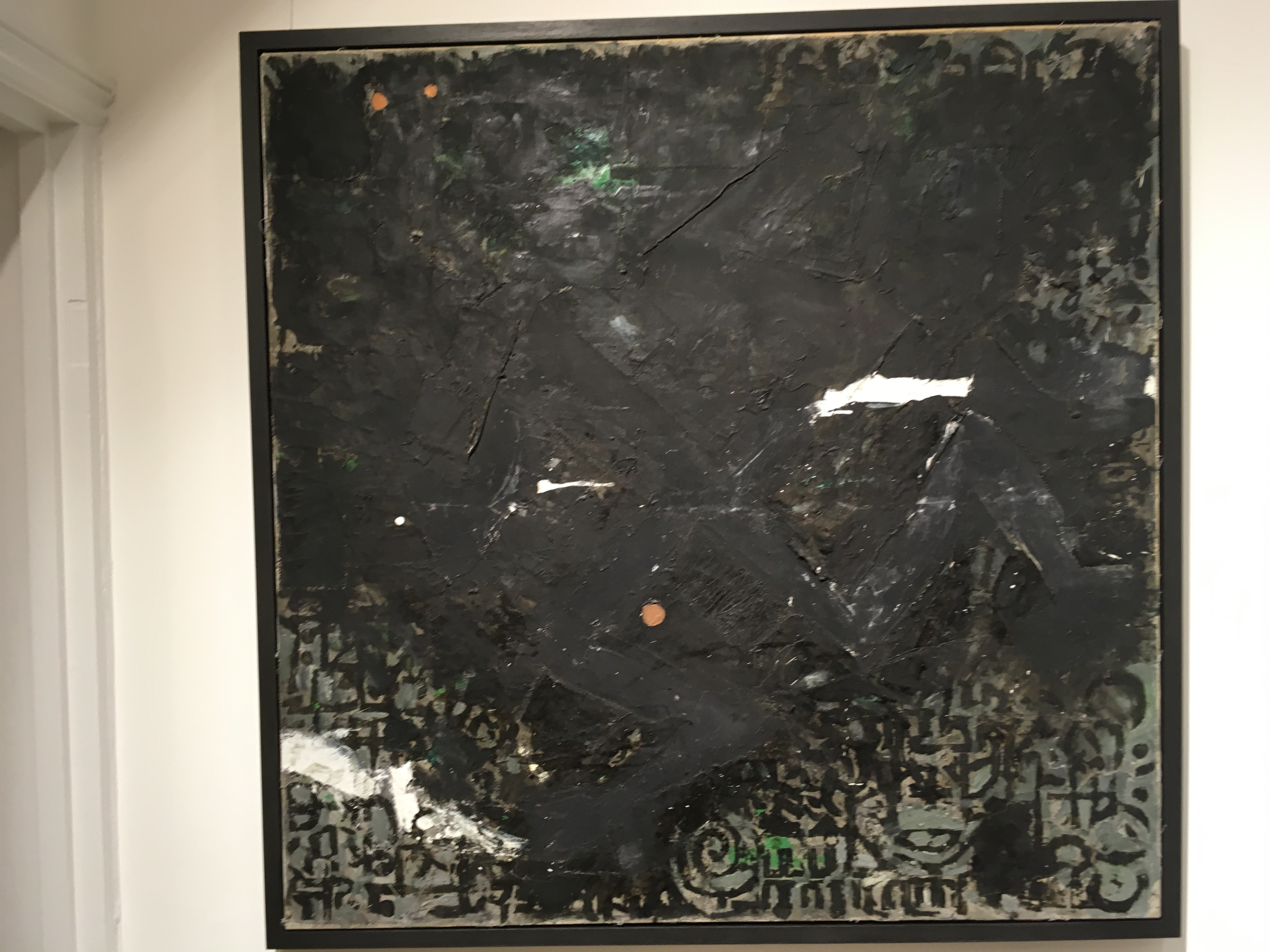

Last we have Signs 1999 where the blackness is almost covering the underlying details referring to ancient symbolic patterns. 1999 is before the great catastrophe, but it feels predictive to me.

Hanaa’s work is also included in the current exhibition at the Imperial War Museum called Age of Terror: Art Since 9/11. I will be writing about that exhibition next.

This entry was posted on October 31, 2017 and is filed under Iraq, Iraq contemporary art in Baghdad, Iraq War, Uncategorized.

Art and Bombs

Part I

Phong and Sarah Nguyen Break into Blossom 2017 with Justin Shaw

As our horrifying President falls for the bullying of North Korea with threats, I am revisiting some important art work that addresses the topic of nuclear war and nuclear pollution. In Seattle, a current exhibition at the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific Experience called “Teardrops that Wound: The Absurdity of War” gives us stunning references to the bomb by descendants of survivors.

“The undetonated bomb is half sunken and surrounded by fallen cherry blossoms.”It is inspired by a chapter in Phong’s book “Einstein saves Hiroshima.” Phong imagines “icons of history make a different choice” it suggests a far different outcome from the death and destruction of dropping the bomb

Yukiyo Kawano Sad Tale of Tanuki

Yukio Kawano suggests the imaginary creatures of mythology in this “Little Boy” created from kimonos from Fukushima sewn with the artists own hair.

Part II History

2001: PLUTONIUM, MARCH 28, 1941,

Ann Rosenthal and Stephen Moore addressed this topic for many years and in many formats. They visited the sites of the tests, of the development of plutonium in Hanford Washington ( now being touted as part of the new Manhattan Project National Historical Park) and they went to Japan to the cities where the bombs were dropped.

Here is a review I wrote of their work from 1995. It is still important today “Nuclear Bombs, Nuclear History and Postmodern Politics” first published Reflex Magazine, 1994 – 1995, Seattle ( I cut out the postmodern politics section, but you can read it on my website)

After a burst of attention following the television “docudrama’ simulating the aftermath a nuclear attack “The Day After, (aired by ABC November 1982) and the disastrous accident at Chernobyl (April 25, 1986) nuclear power is currently “out of fashion” as a publicized subject for political art. But as the risk of nuclear components in the hands of terrorists continues, as do the health hazards of its production and storage, nuclear power is still an issue and a presence that we cannot afford to forget.

The recent (1995)uproar in Congress and among veterans’ groups over an exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the dropping of the bomb reveals, atomic bomb history and nuclear power is still a carefully edited story. Ann T. Rosenthal and Stephen Moore in their installation have produced a reminder, in response to that same anniversary, of the ongoing presence and dangers of contemporary nuclear power as well as a roadmap of that edited history.

“Infinity City” overlays and juxtaposes cultural artifacts in many media as a metaphor for the multi-layered and ambiguous presence of atomic and nuclear power in our lives and in history. It avoids the predictable quick hit cliches-there are very few mushroom clouds and they are small, encompassed in other imagery. The emphasis is much more subtle. It asks us to use our intellect as much as our emotions.

The exhibition has several parts.

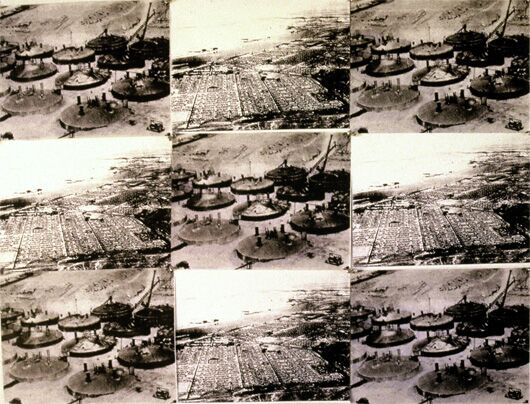

The first part, “Tricity Trinity” marks a US map with the atomic triangle, the Pentagon, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Invoking the latter are blown-up blue line prints of tight rows of the lethal, leaking waste storage tanks at the Hanford Plutonium Plant. The waste tanks are paired with the orderly suburban houses of nearby Hanford, Washington, a community built after obliterating the preexisting community.

The second part of the show “Eternity Ignored” includes manipulated photographs of the abandoned runways at the military base at Tinian Island in the north Mariana Islands (halfway between New Guinea and Japan).

An eerie antithesis to a South Sea paradise, the wide, empty runways have small signs landscaped with flowers that mark the deep pits used only once, for loading the huge atomic bombs Little Boy and Fat Man onto B 29 planes. The site is striking, according to the artists, for its lack of historical documentation, its air of a military ghost town. That sense of the horrific transformed into the trite and the obscure is captured in their understated images.

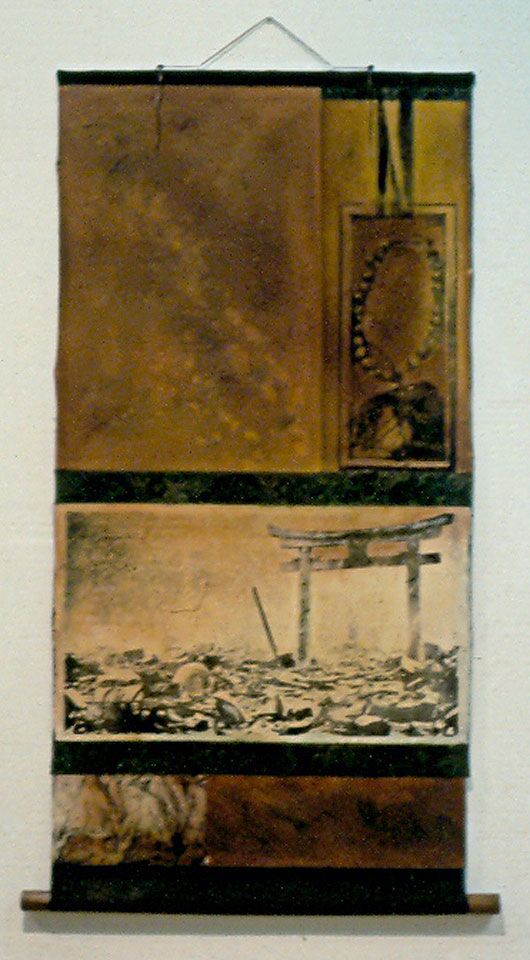

The third part of the exhibition is titled “Target Japan.” It includes paintings invoking Japanese scrolls that overlay an aerial photo of Hiroshima Ground Zero with the very young men of the crew of the B 29 and the current Peace Park at the site. . . .

Marking the back of the exhibition, and metaphorically casting its presence over the entire show, is a full scale black outline of Little Boy.

But for Ann Rosenthal and Stephen Moore these objects are only a point of departure. They are hoping to generate awareness, questions and even activism. On a table are books such as “Nuclear Culture”, “Missile Envy”, and “The Day the Sun Rose Twice”, as well as clippings about the current health problems from the plutonium production plant at Hanford. A news article details an exuberant Tri Cities near Hanford as the recipient of huge clean up funds that are ensuring the economic survival of the city for years to come.

The artists want to not only reach people with the subject, but give them possibilities for expressing their feelings within the exhibition itself. They provided an area for adding a work of art or a written statement. One such piece was by a Japanese student who remembered, in a stirring drawing, the shock of visiting the Hiroshima Peace Museum as a child.

Residents of Eastern Washington State commented that they have relatives who are downwinders from Hanford, relatives who helped build the bomb, relatives who fought in the war.

Most believe that dropping the bomb ended the war and saved lives. These responses add more layers to the cultural history of atomic and nuclear power and make the exhibition more effective than the use of a more controlled, didactic approach.

The artists have on ongoing involvement with the subject. They believe that “the atomic bomb changed our whole perception of reality and the future.” In 1982 they created several performances in Los Angeles as part of a group of six artists called UNARM. The group focused on the death and horror from just one nuclear detonation and sought to “raise the public awareness of the irreparable consequences, both physical and psychological, of the folly of nuclear proliferation.”

. . . . .

Rosenthal and Moore communicate by undermining a simple and dominant cultural myth – that American technological brilliance solves problems, wins wars, and of course “makes everything all right.” Underlying it is our knowledge that technology is actually destroying the planet both physically and psychically, in the microcosm and the macrocosm. Infinity City presents fragments of the invisible presence and history of the largest and most obvious psychic and physical manifestation of that destruction and of the misplaced values of our culture, atomic and nuclear energy.

Note: This article was written in 1994. The project continued for many years. Stephen Moore died in 2006, but Ann Rosenthal continues to be actively engaged with opposition to nuclear weapons.

See Ann’s own discussion of her work.

Part III “It is Heavy on my Heart” (2002)

Artist’s Statement Gail Tremblay

Gail Tremblay Lung and Diaphragm Tumors in a case of Epithelial Mesithelioma with embedded sound

“I first became aware of the effects of nuclear pollution on reservations in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s when I began reading about rising cancer rates on the Navajo reservation. Because piles of radioactive dust and rock (tailings) from uranium mining had never been cleaned up by the corporations who did the mining, people living in areas on the reservation where the mining was done were suffering from the health problems associated with long term cumulative effects of radiation exposure.

Next, I heard about the effects of the Nuclear Testing of Atomic Bombs in Nevada on the health of the Shoshone peoples there. Then I heard about the negative health effects on Yakama and Coleville people caused by radioactive emissions and spills from the power plants at Hanford Nuclear Reservation where the earliest reactors were used to enrich uranium and create plutonium for the first nuclear bombs.

During the long period of the Cold War when several countries were testing nuclear weapons, people around the Arctic were exposed to large doses of nuclear fallout, and I began to hear stories about the health effects on Inupiat and Inuit peoples. Because indigenous people in all these places hunt and/or fish and gather local plant foods also exposed to radiation, native people concentrated much higher rates of radiation in their bodies than many non-native people in surrounding areas.

People who lived a less tradition life style and bought food in grocery

stores that was shipped in from less contaminated areas would still suffer from health problems, but generally there exposure levels were lower unless they grew and raised their own food.

At the same time, the U.S. government supported corporations like General Electric to develop Nuclear Power Plants, and this policy generated an incredible nuclear waste problem. U. S. officials eventually decided to look to reservations to create Monitored Retrievable Storage (MRS) facilities to house that waste while a permanent storage facility was built.

During the 1990’s, large amounts of money was paid to several tribal governments to do feasibility studies. When people in the various tribal communities being studied learned that their reservations were being considered, movements to stop MRS sites from being built divided communities into factions where large numbers of people didn’t want to risk radioactive contamination if an accident occurred. The U.S. government targeted reservations because they are by treaty sovereign nations and U.S. citizens in surrounding communities and states have no control over them. Many communities are still feeling the negative effects of this U.S. policy in their relationships and on their lives.

Current U.S. nuclear policy calls for building a permanent storage facility at Yucca Mountain, a place where much of the early testing of Atomic Bombs was done. Yucca Mountain lies on an earthquake fault and both the Shoshone people and millions of non-Indian citizens of the state of Nevada oppose this policy. Current U.S. Nuclear Posture Statements also call for the building of new nuclear power plants that will create more nuclear waste,the development of new, small nuclear weapons for use in “limited” nuclear wars, and the testing of these new weapons. One wonders how many more people

will suffer from rising cancer rates, birth defects and other health

problems related to nuclear pollution if such a policy is implemented.

Such policies are dangerous for all people on the planet, not just future enemies of the United States government, the only country to use nuclear weapons in war. But for people in indigenous nations who are most likely to be impacted by future mining, testing, or waste disposal, current nuclear policy statements are plans by the U.S. government to commit more, possibly genocidal, international crimes against humanity. It is immoral when a government endangers the right of peoples in nations inside their boundaries

to a healthy life practicing their traditional life ways on this planet,

Mother Earth, who has sustained life for countless generations. In the face of such policies, it is time for all Americans to stand up for the health of the planet and the health of all the beings on it. One needs to think about rising cancer rates among friends and relatives and to chose leaders who will make policies that are not quietly killing the people one loves.

Decisions that are not good for people being born Seven Generations in the future are bad decisions. No one should choose leaders who make bad decisions.

Gail Tremblay

This entry was posted on August 10, 2017 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, Contemporary Art, Contemporary Indigenous Art, Gail Tremblay, Uncategorized.

Deborah Faye Lawrence: A Strumpet of Justice tells it like it is

In the window of Bonfire Gallery in the Panama Hotel, we see DeeDeeLorenzo (the artist’s alter ego) crying. She wears her signature flag dress, but now in somber dark shades, as she surveys the shambles of disheveled flags around her.

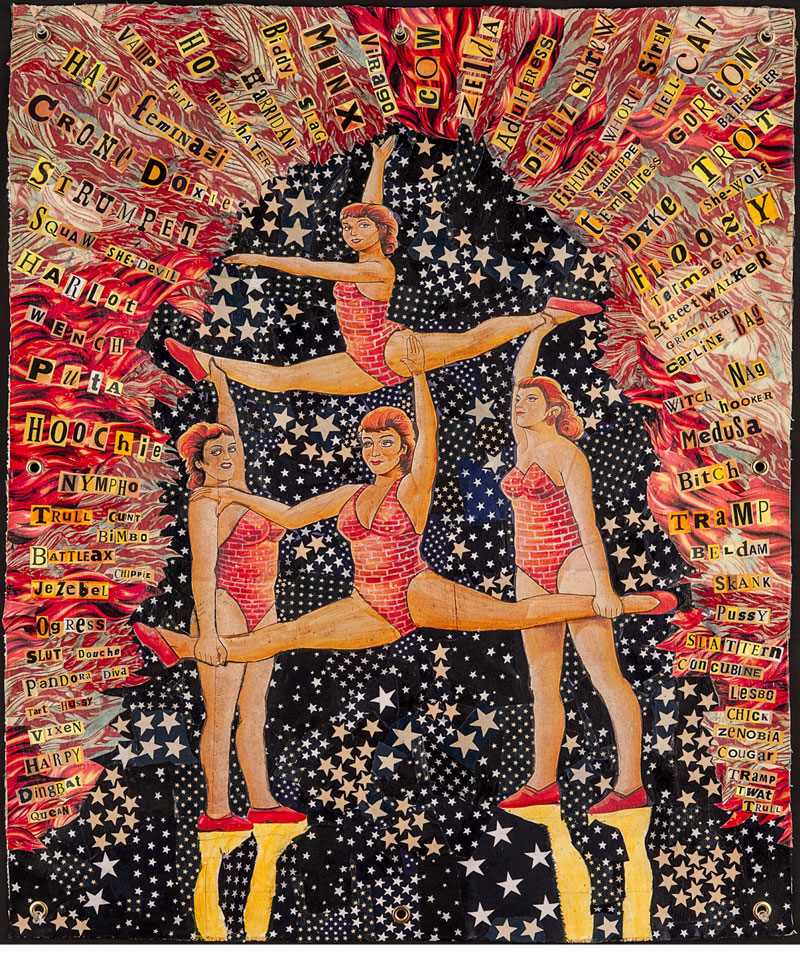

That sadness sets the tone for the cries or even screams in “Strumpet of Justice.”

In the title piece a determined female, plays an accordion emblazoned with a heart in the midst of stars in a blue field, cut from flags. According to the artist, “a strumpet is a slovenly woman, a strumpet of justice puts aside lovelinesss in her efforts to change the world.”

We are immediately immersed in resistance on every wall as we enter the Bonfire Gallery. Flags surround us, but these flags do not wave in loyal patriotic gestures. Rather they speak to the artist’s strong message of opposition to what is happening in the world.

Lawrence has included some of her more crucial older works, particularly her two part Assassination Day Trays 2004 which recalls a personal experience on the day of Martin Luther King’s assassination.

Leonard Peltier Tray 2000 “honors the Native American activist who has spent most of his life in U.S. prisons” as the artist explains.

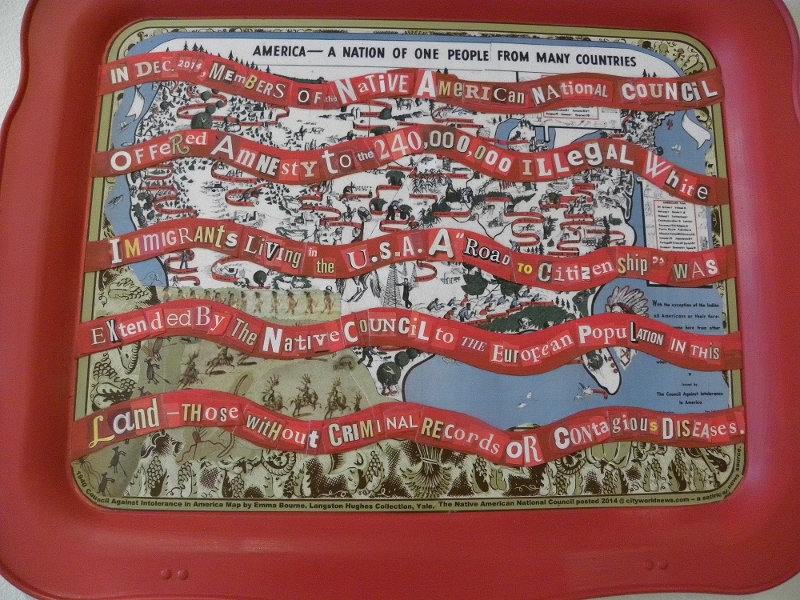

Also about Native Americans, American Amnesty Tray declares amnesty for white people by Indians.

But many of these works are recent or even just created in response to our current horrifying political situation.

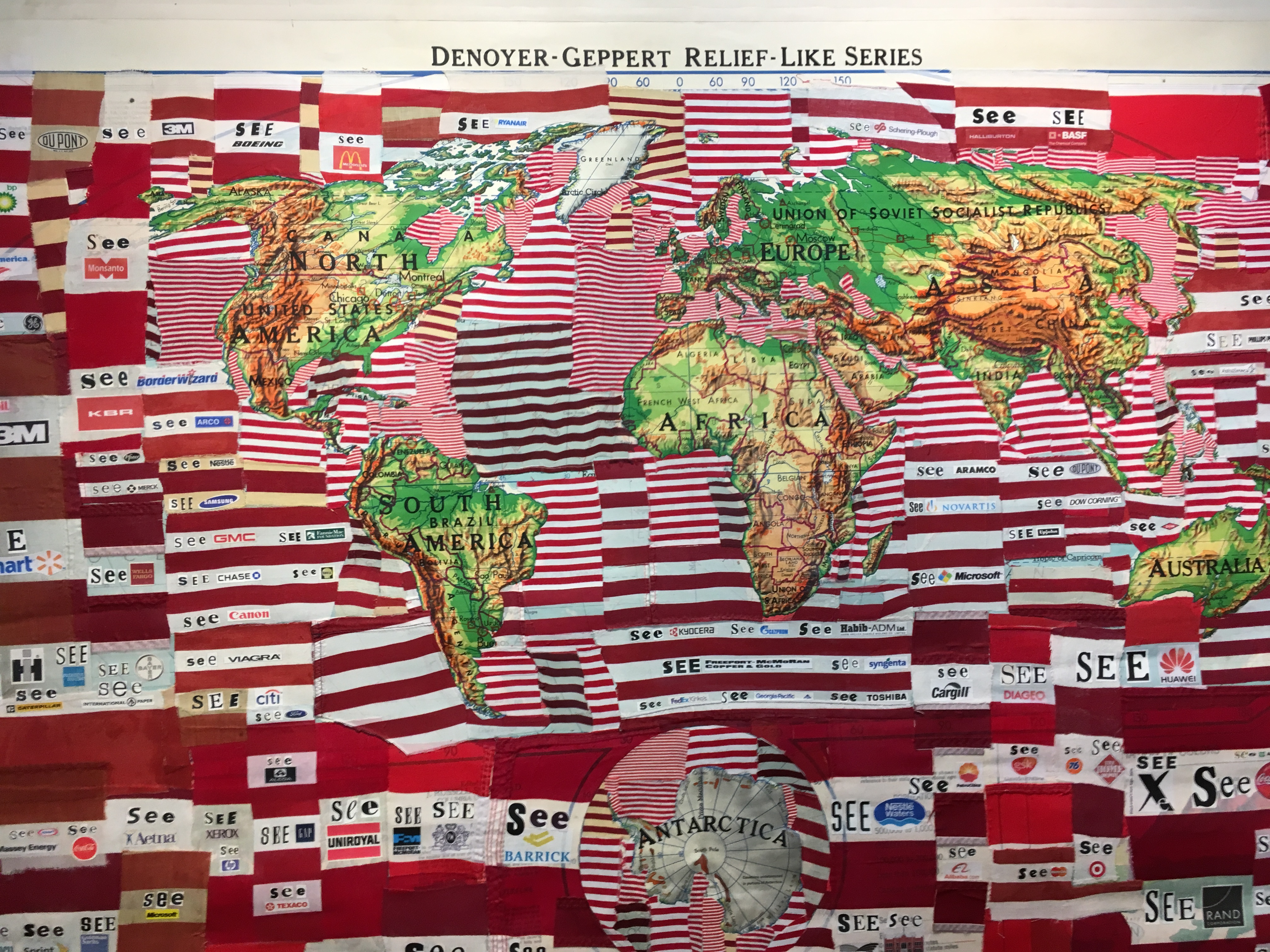

Several themes appear repeatedly including feminism, concern for the planet, corporate exploitation, gun fanaticism, and manipulation of language. Sometimes the artist defiantly exposes evils, such as the ongoing destruction of the planet by corporations.

In Targeting the American Dream, 2011 * shown here in a detail) the target painted on the elk dominates a landscape littered with corporate logos and set in a centrifugal arrangement of flag stripes.

See How We Are, 2011 echoes the simplistic children’s book Dick and Jane but what we “See” are Corporate Logos everywhere.

On the theme of feminism, Eighty Words, (2014) declares that no matter how many crude expressions insult women, they still defy them all with an exuberant energy and solidarity. Under the Banner, 2014 documents the many ways that a woman’s body can be occupied by corporate poisons.

The manipulation of language, always a favorite of the artist appears in Original Pledge, which documents the sources of the Pledge of Allegiance as written by Ralph Bellamy, a utopian thinker of the 19th century. Revisionism explains in detail how documents and prinicples have been “rewritten to the advantage of dictators,”

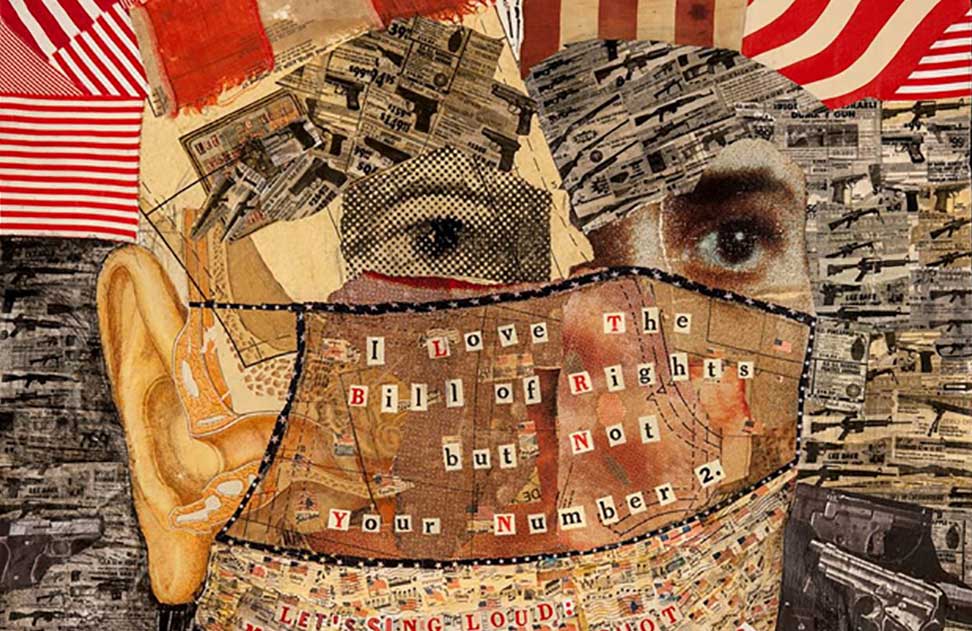

Finally, intersecting with her opposition to gun fanaticism is the manipulation of the second amendment which Lawrence spells out ( literally and figuratively) in two works on gun fanaticism, Open Carry 2016, ( detail above) and NRA Sweepstakes. 2016.

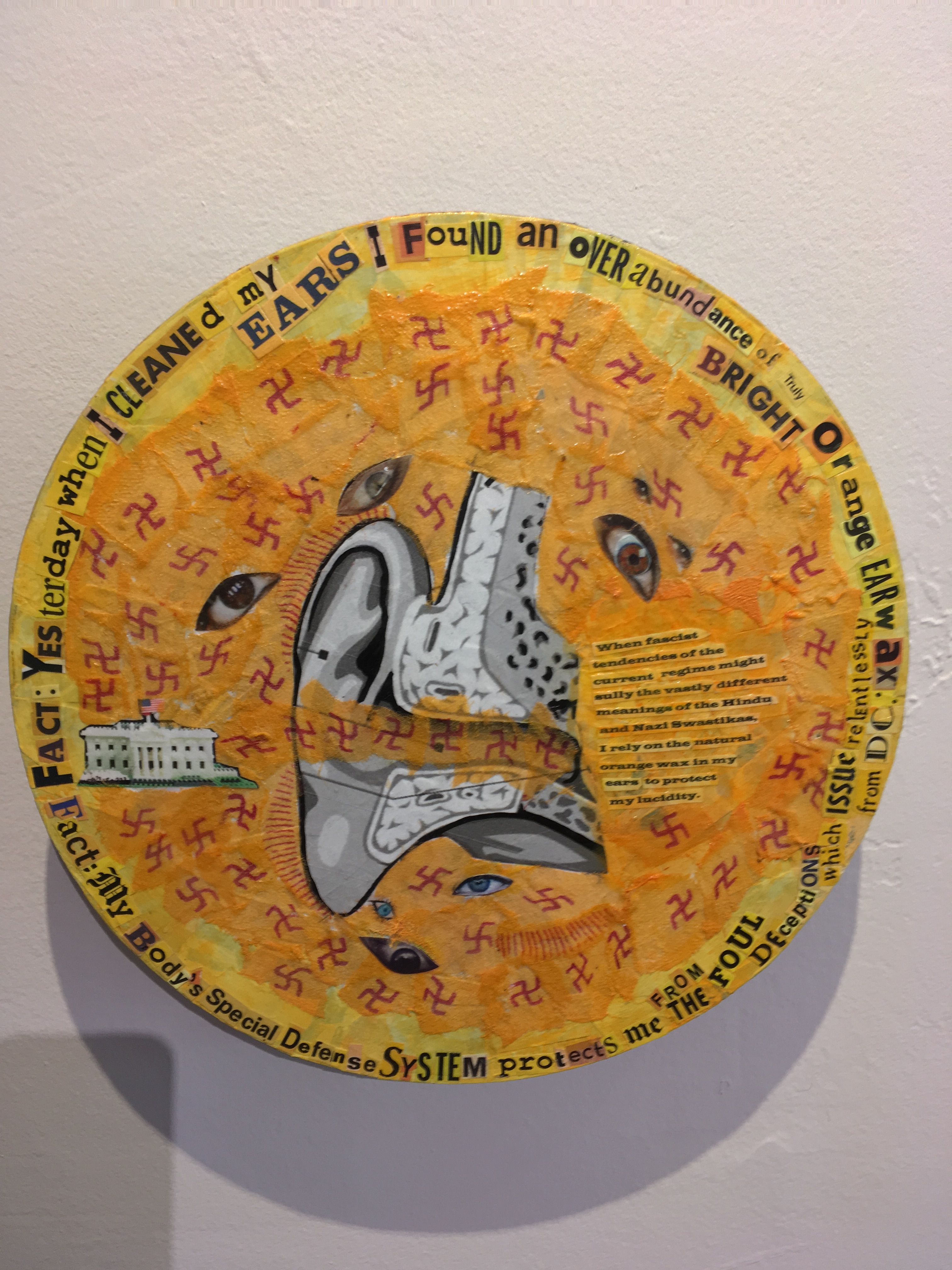

But without question, a small recent work hits the nerve of our present moment most precisely. Called Ear Wax, it depicts a large ear on a yellow ground. The text around the outside describes the “overabundance of orange ear wax” that came out of her ear which is explained : “Fact: My body’s special defense system protects me from the foul deceptions which issues relentlessly from D.C.”

This work captures our bodily nausea and horror as we observe the arrogant and wanton efforts to destroy everything that we hold precious: our planet, our bodies, our diversity, our freedom, our basic belief in opportunity and health care for all. But as the Strumpet of Justice, Deborah Faye Lawrence, tells us, we can and must resist in every way that we know how. Pick your issue and get involved! We cannot afford to withdraw or give up. Our future is on the line.

Thank you Deborah for your inspiring work.

Immigration: Hopes Realized, Dreams Derailed The exhibition,the poetry and the music

Spaceworks Gallery Tacoma, June 20 – August 17, 2017 M – F 1-5

950 Pacific Ave. #205

Tacoma, WA 98401

(Entrance on 11th St.)

Third Thursday until 9PM. Multimedia Program August 17

Entrance Shot by Scott Story, Bioluminous, all photos with astericks by Scott Story

INTRODUCTION

Only one mile from this gallery, in the toxic, industrial zone of Tacoma, the Northwest Detention Center, holds hundreds of detainees in a warehouse. Run by the for-profit corporation GEO, the government (that is us) pays more than 100. 00 for each bed occupied each night. The detainees do all the work of the center for $1. per day. They are treated like criminals, but they have committed no crimes. Crossing a border with correct visas is a “malum prohibitum” wrong only because the law prohibits it, not because it is morally wrong. (malum in se). It is a civil offence. People who have crossed borders without papers are escaping violence, and simply seek to support their families in safety. To get legal papers in Mexico or in the US is virtually impossible. The DREAM act first supported by President Bush in 2005 provided the crucial “path to citizenship” but it failed in the Senate in 2010.

But behind these facts and statistics are the personal stories of mothers, fathers, children, aunts, uncles, grandmothers and friends who live in fear every time they wake up in the morning, but resolutely go to work, care for their families, and maintain hope.

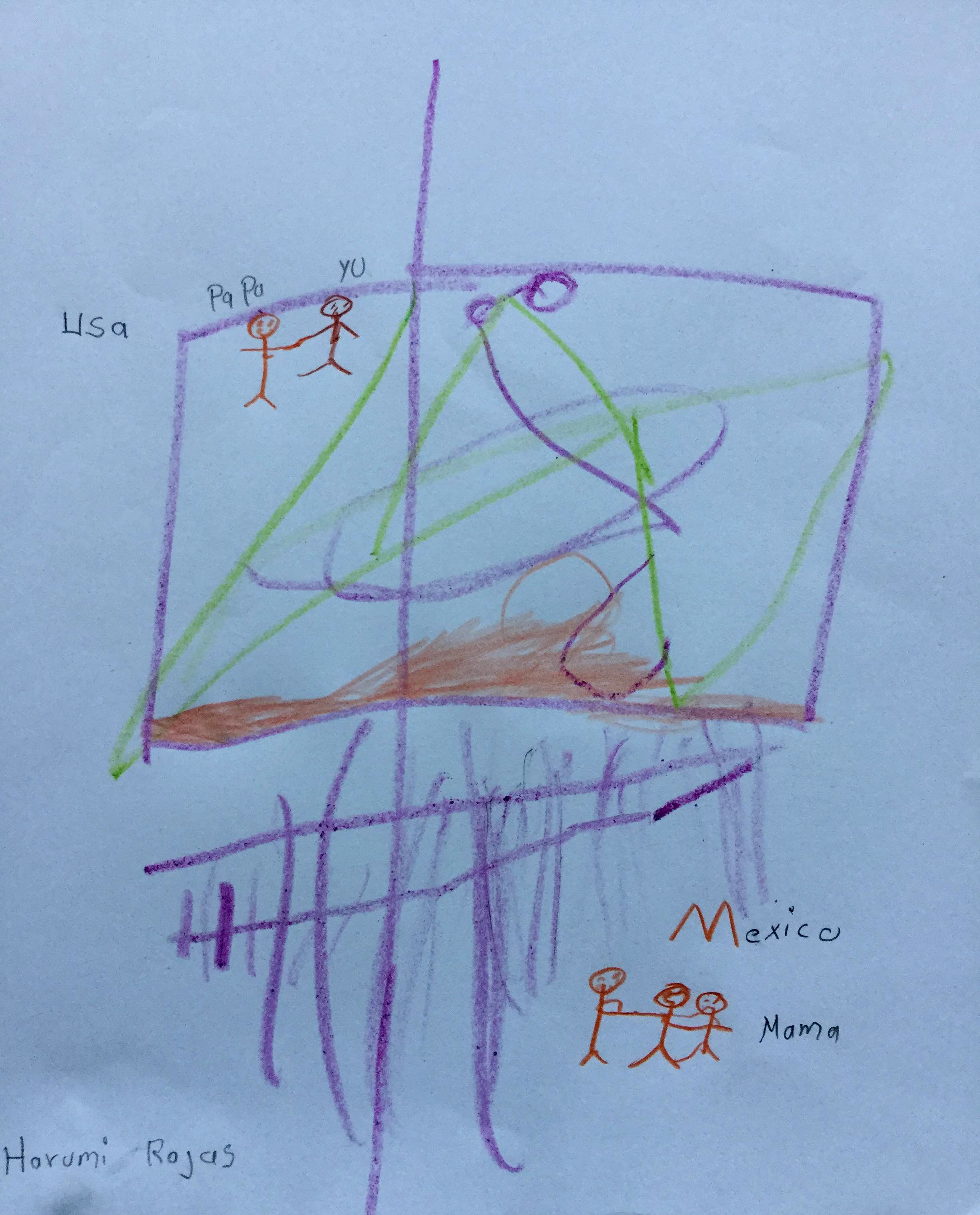

Children’s drawing created in response to question How have immigration laws affected you at a May Day booth organized by Susan Platt and Raul Sanchez

Children live in fear. Youth live constricted lives because they lack social security numbers, drivers’ licenses, even library cards. The Delayed Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) has given some of them a way forward, but the program can be cancelled at any moment.

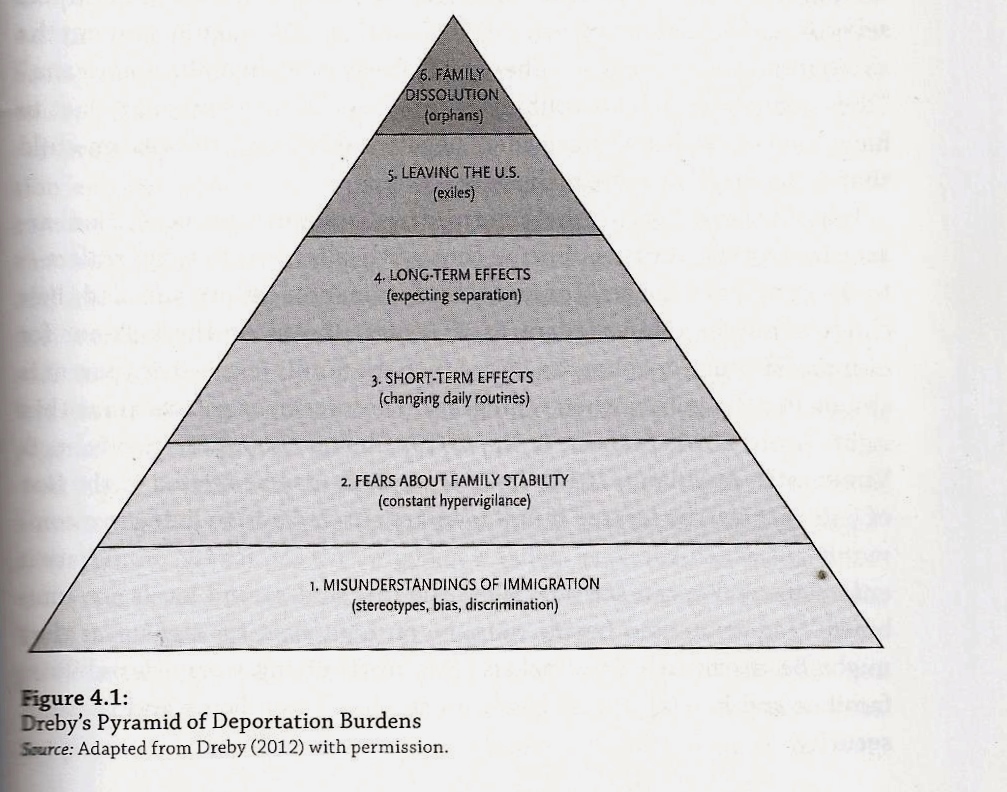

At the same time, the deportation of parents make orphans and exiles of thousands of citizen children every year. Here is a pyramid of anxieties as illustrated in the book by Luis Zayas Forgotten Citizens, Deportation, Children and the Making of American Exiles and Orphans. The illustration is by researcher Joanna Dreby.

Hardworking families saving money from two or three minimum wage jobs lose it all to an unsavory lawyer. Savings for a college education goes to enable a deported father to return to his home and family. The vivid book by Roberto Gonzales Lives in Limbo Undocumented and Coming of Age in America describes these events as he follows children into young adulthood.

Eduardo Trujillo performing his poetry*

But there are also success stories, stories of resistance, of defiance, of courage. These are even less reported in the media, more frequently stories we don’t hear.

Installation*

“Immigration, Hopes Realized, Dreams Derailed” suggests some of those stories of courage, of defiance, of perseverance, of hope and dreams, as well as including the dark side of immigration, most specifically here in Tacoma, at the Northwest Detention Center itself.

Ricardo Domingez poster at entrance*

The artists, poets, activists, and musicians in this exhibition and programming shed light on our current immigration policies, its damage to individuals and families, its injustice, its corporate roots, its absurdities and the courageous individuals who resist.

We include painting, sculpture, drawing, collage, glass art, film, photography, and video as well as poetry, music and spoken word. The works range from heartfelt to playful, from interactive to informative, from poetic to didactic. The artists, poets and performers include undocumented immigrants, former detainees, current detainees, DACAs, college students, self- taught artists, and professional artists.

THE ENTRANCE

At the entrance to the gallery, you see a painting by Blanca Santander, Esperanza Abandonada (Abandoned Hope) depicting a doll impaled on the other side of a barbwire fence. Its poignant image of a child who has lost her beloved doll, crossing the line into another place, a child who has left behind childhood, familiar languages and culture, as well as a life close to the land, speaks directly to the hardships of fleeing home to enter an unknown place.

Tatiana Garmendia 3 Joses ( center) and A Green and Peaceful Neighborhood ( left and right) 2017*

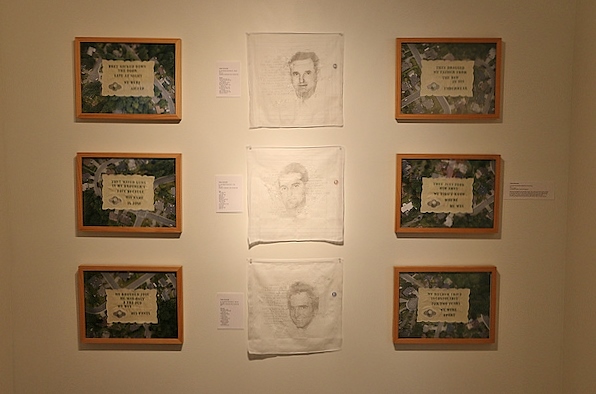

In an alcove just to the right is the installation of the work of Tatiana Garmendia. Pale pencil portraits and texts drawn on distressed handkerchiefs honor three generations of men in her family: grandfather, father and son (her brother). We feel the tearing of family as the artist distressed the surface of the handkerchiefs. Her pale writing and drawing on the white background suggests holding onto a disappearing memory. But she brings them to us through her poetic invocations.

The handkerchiefs are framed on both sides by embroidered doilies mounted on drone shots of a suburban neighborhood. On each doily the artist carefully embroidered brief searing references to a nighttime raid based on her own experience in Cuba, but as she states, “it can happen anywhere, anytime. Geographical differences and generational distance between persecuted groups vanish in light of human suffering.”

Maria de Los Angeles Undocumented 2016

Indeed, this emotional trauma is echoed in the drawing in the main gallery by

Maria De Los Angeles, “Undocumented,” in which we see a family trying to protect themselves and resist an invasion by ICE officials who spout off nationalist clichés. De Los Angeles, an artist who is undocumented, bravely explores the nightmares of detention raids in her work.

Maria de Los Angeles Holding Everything Up, 2016

She also honors those who work in her small drawing Holding Everything Up: a man and a woman balance on a ball, as they struggle to support a floor that holds up oblivious party goers.

The VIDEOS

The video viewing room includes several videos, two by Tatiana Garmendia.

Tatiana Garmendia Still from video Border Crossing

In Border Crossing, 2015, the artist lies almost naked face up, with eyes staring, as we hear a partially coherent series of phrases “the mouth of the border has nothing to say; my border is a mouth; you crossed with nothing to say; why did you cross my home,” and many more variations on these words taken from Reza Mohammad’s poem “You Crossed the Border.” The motionless body is spotlighted from above, as though a surveillance airplane has found her.

Viewing the Unravelling*

Garmendia’s animation The Unravelling, 2017 functions as both a prose poem and a visual journey that dramatically tells of her father’s arrest and her mother’s grieving.

Detention Nation an activist artists’ collective based in Houston, present their installation Sin Huellas (Without a Trace), through the video by Brenda Cruz-Wolf. Sin Huellas recreates the inside of a detention center, with lined up bunk beds and toilets conveying the complete lack of privacy in these facilities. Videos, letters and artwork document the horrifying day-to-day experiences of detainees.

The Wall, by Hide and Seek Productions, is an animation of a grandmother and her grandson fleeing a flaming city, and their struggles to survive and escape a refugee camp next to a wall.

Finally, Think Like a Scientist: Boundaries, gives us the photographer Krista Schlyer who spent the last seven years documenting the environmental effects of the U.S./Mexico border wall, and biologist Jon Beckmann, who studies how man-made barriers influence the movement of wildlife. The video combines animation and film to highlight the huge ecological impacts of a dividing wall on animals that traditionally migrate through this border territory.

INSIDE THE GALLERY

Clarita Malla left, MalPina Chan prints on wall, Pavel Bahmatov central display*

Inside the gallery, we immediately face the stunning work of Pavel Bahmatov, purses, boxes, and other objects, created when he was detained in the Northwest Detention Center(NWDC). Using ramen wrappers and dental floss, Bahmatov weaves together objects of great beauty. He speaks of alleviating the immense boredom of detention by making these objects. Bahmatov was abruptly moved to the Dalles in Oregon this spring. He is currently at a County Jail, an even worse environment that the Northwest Detention Center.

Detail of hats by Clarita Malla*

Currently in the NWDC Filipina Clarita Malla creates woven scarves and hats as her ongoing separation from her family and her grandchildren endlessly stretches from one hearing to the next, from one month to the next.

MalPina Chan A Nation of Immigrants in Pursuit of Happiness, 2017(left) and Underneath it all, we are all the same, 2017 (right

MalPina Chan, in her subtle layered works, speaks of the hypocrisy of our policies compared to our rhetoric, as well as pointing out that “we are all the same” in a dramatic count of the bones, organs, and amount of water in every human.

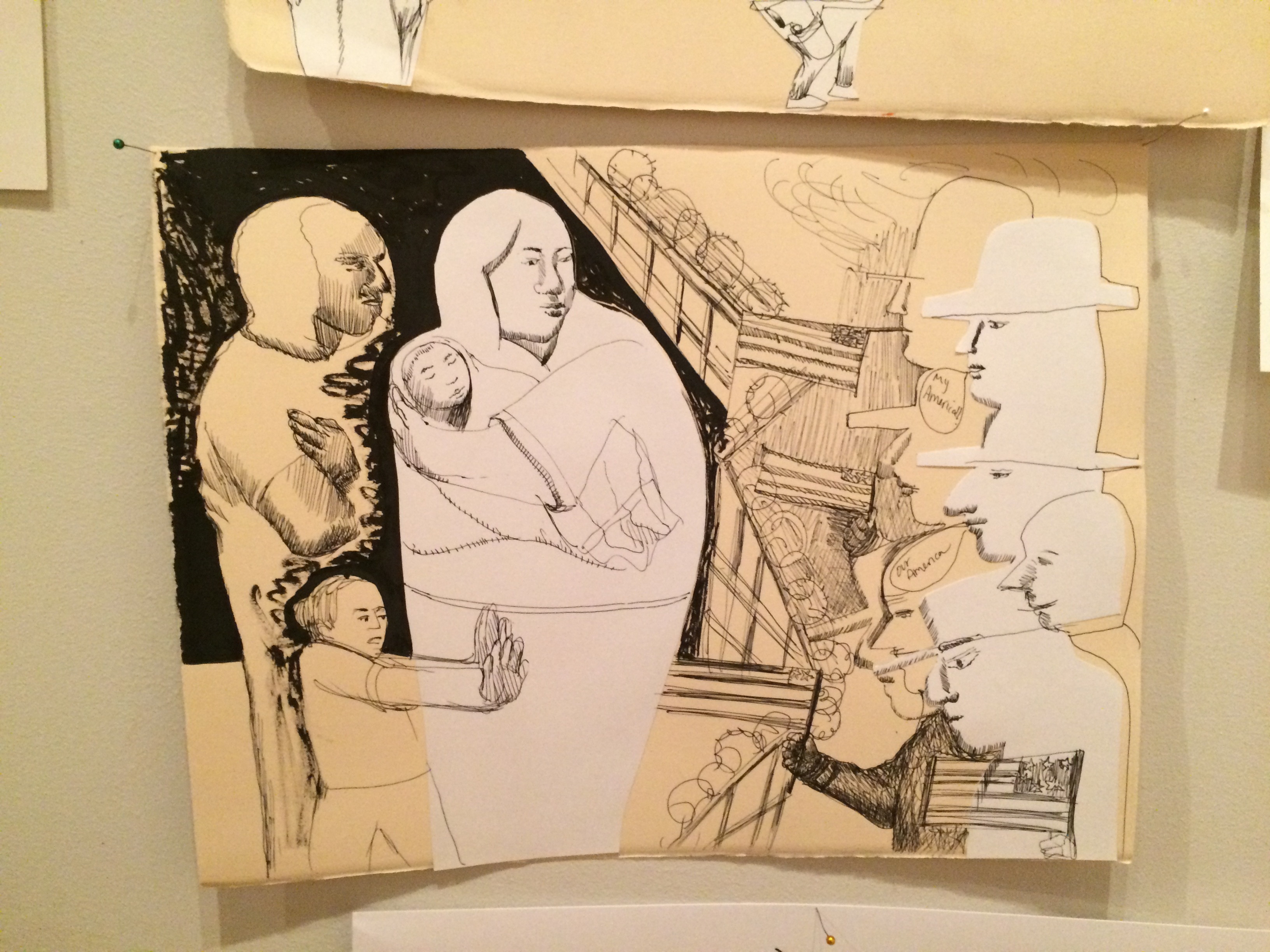

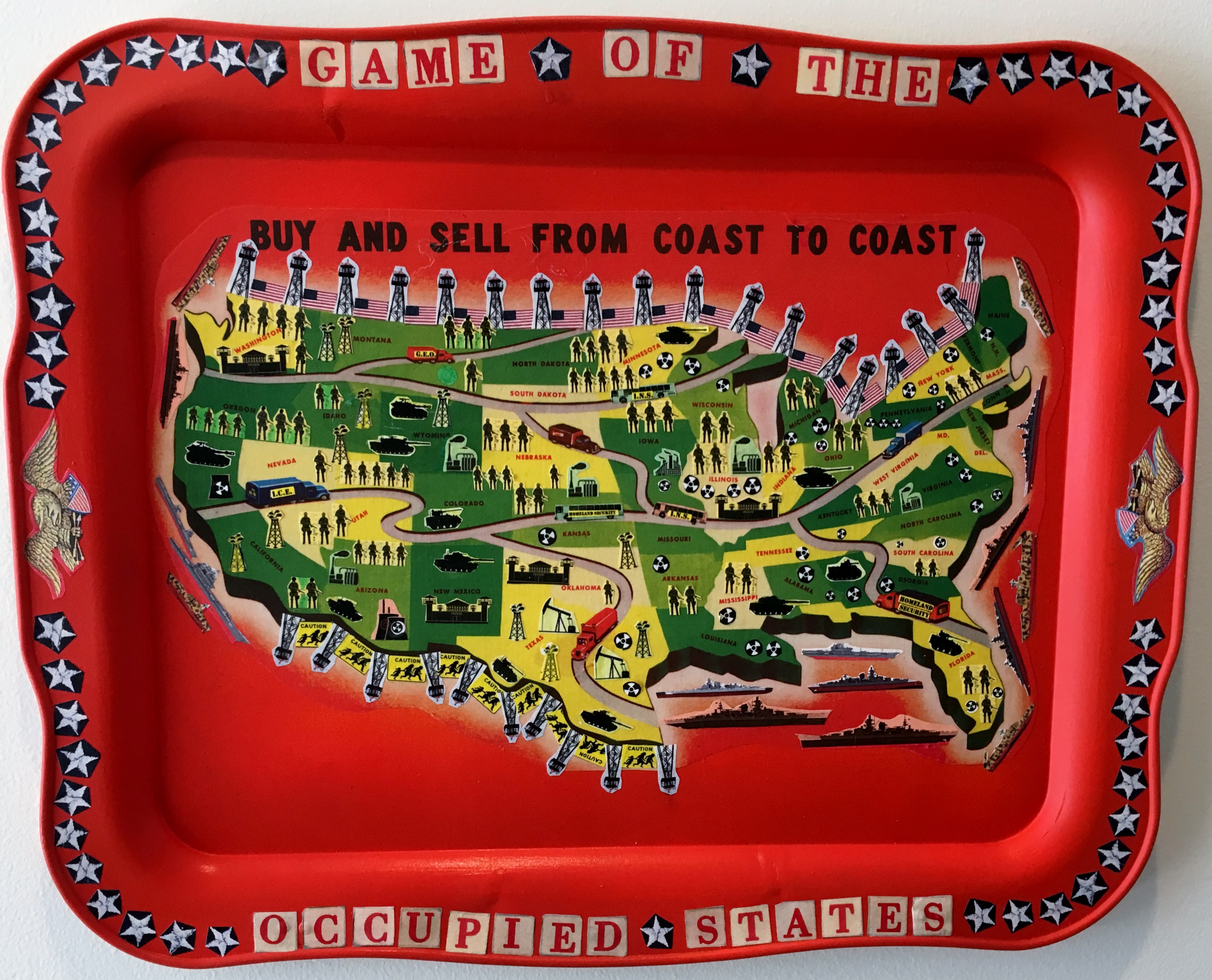

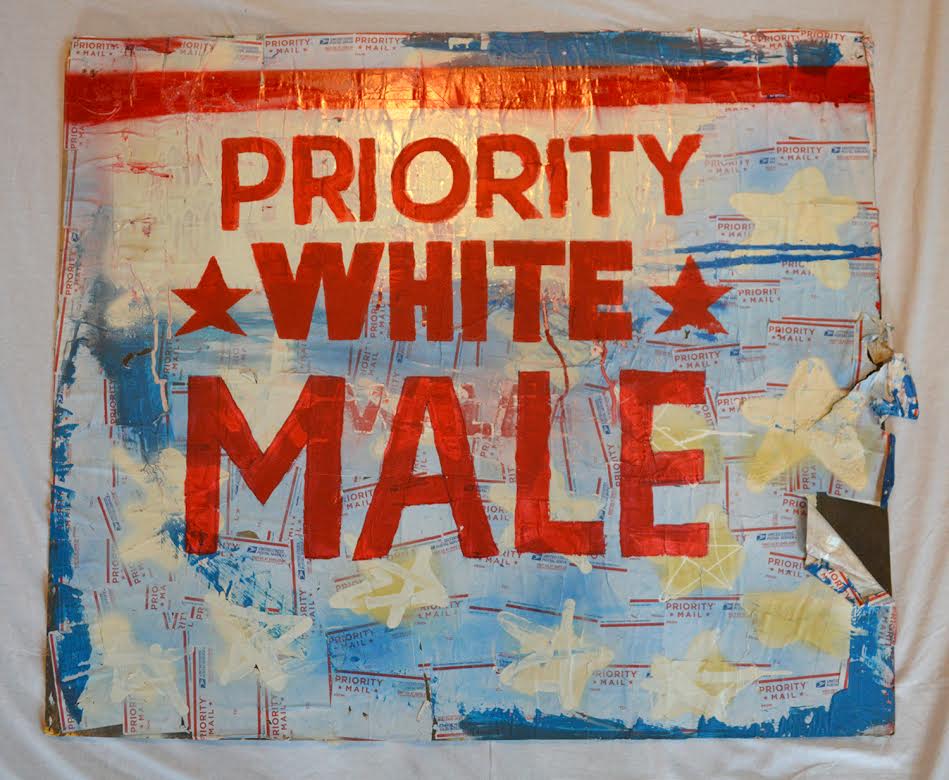

Deborah Faye Lawrence Game of the Occupied States

Deborah Faye Lawrence’s intense bright red “tv dinner tray” collage Game of the Occupied States, (“Buy and Sell from Coast to Coast”) provides a chilling image of a police state with surveillance towers punctuating a border fence around the whole country. Criss-crossing the country are tanks, soldiers, and transports run by prison companies.

Janice LaVerne Baker, Immigration, 2014

Janice La Verne Baker quietly conveys the anxiety of confrontation with immigration officials,

while Arni Adler speaks to the same subject in Ushering In ( above right) and the Welcoming,( above right) painted in direct response to outpouring of protest to the “muslim ban” that the current administration attempted to introduce in January.

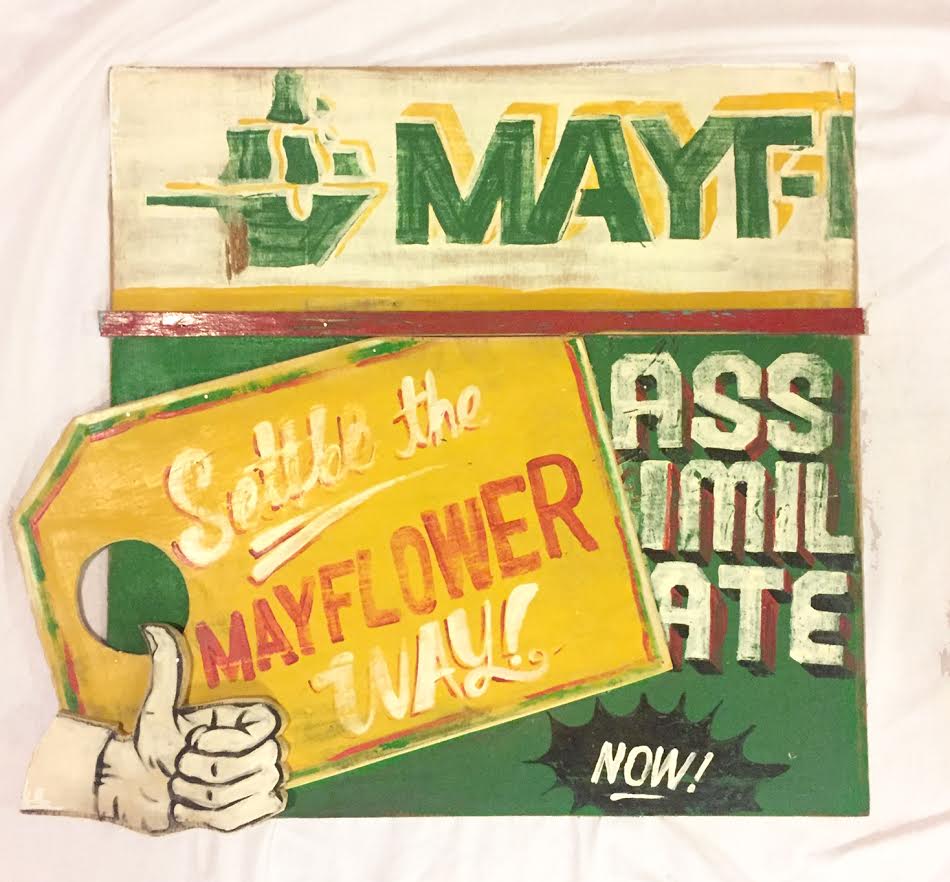

Devin Reynolds’ bold paintings provide an historical as well as a humorous reference to the unavoidable fact that racism underlies the entire subject of immigration, from the first white settlers to the present day.

Pam Orazem*

Pam Orazem amusingly caricatures the power games of the manipulators of immigration policy.

Andrea Eaton’s silkscreen print Guadalupe Garcia,

and

Marilyn Montufar*

Marilyn Montufar’s photograph Dani (one of a series following Dani’s life) both refer to women who face the challenges of deportation. Montufar’s small portraits on glass pay homage to two of the many women who have lost their lives in Juarez, Mexico as they attempted to make a living at the maquiladora factories on the border.

Christian French INS Game*

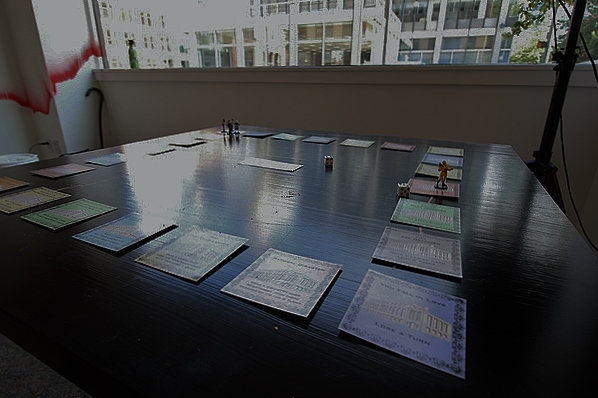

Christian French invites us to play a board game. He suggests the constant back and forth of the Naturalization process, with one step forward, and two steps back. The original of this work is embedded in the floor of the old INS (Immigation and Naturalization Service) building in Seattle, that has been transformed into artists’ studios. The fact that that center included Naturalization whereas the Northwest Detention Center serves, with only a few lucky exceptions, as a way station to deportation, tellingly exposes the shift in our policies to increasingly draconian approaches.

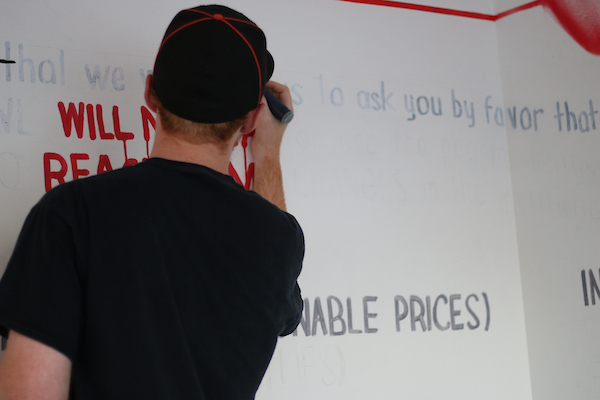

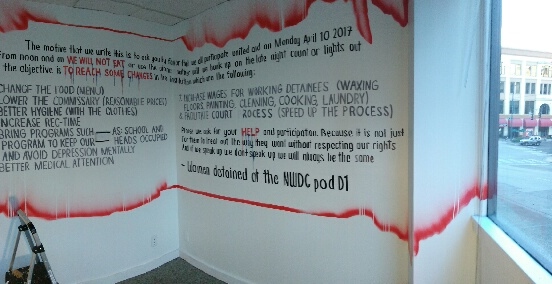

David Long painting mural*

David Long’s

mural partners

with our video “Sin Huellas” (without a trace). He gives us the words of the Hunger Strikers demands at  the NWDC. We see the terrible conditions the detainees are subjected to when we read this letter. None of their demands have been met.

the NWDC. We see the terrible conditions the detainees are subjected to when we read this letter. None of their demands have been met.

Nearby the writings and drawings by children created in a May Day project with Raul Sanchez and myself in 2016, speak loudly to the trauma of immigration policy as it strikes the young. ( see top of post for an example)

Ricardo Gomez created a group of sculptures from found shoe shine boxes. As we open each box, called Portrait of a Migrant, we see our face reflected back from a mirror inside. We all migrate, he says, we all move from one place to another, adjust to new cultural contexts.

In Two Sides of the Wall, he simply placed a saw diagonally across a labyrinth game, with workers made from Lego pieces on each side.

The interactive poster, Where do your ancestors come from? Invites us to add our own information going back four generations.

Last, Gomez in collaboration with Angie Tamayo assembled the Mi-gra-tion book in a flip flap format, here embroidered by a Woman’s Collective in Oaxaca. Migrants tell their stories. As we “flip-flap” through the three part texts and photos, we hear shared experiences in many voices.

There are two groups of work in the exhibition First there are selections from the 2012 Migration Now portfolio (organized by Justseeds/CultureStrike).

Installation Migration Now*

Viewing Migration Now*

The Migration Now portfolio created by nationally known artists includes reference to many aspects of the immigration crisis, including corporations profiting from the detention centers and the devastating impact of immigration policies on indigenous peoples, families, children, LGBTQ, and Muslims. Some confront the environmental catastrophe of the wall, reinforcing our video Think Like a Scientist: Boundaries

Migration Now Portfolio artists, sponsored by Justseeds /CultureStrike: Lalo Alcaraz, Santiago Armengod, Felipe Baeza, Jesus Barraza Melanie Cervantes, Raoul Deal, Emory Douglas, Molly Fair, Art Hazelwood Ray Hernandez, Nicolas Lampert, Josh Mac Phee, Dylan Miner, Oscar Magallanes, Colin Matthis, Fernando Martí, Oree Originol, Favianna Rodriguez, Roger Peet, Shaun Pete Yahnke Railand, Julio Salgado, Silfer and Janay Brun, Meredith Stern, Mary Tremonte, Erik Ruin, Kristine Virsis, Ernesto Yerena

Viewing Arni Adler and student portfolio

Second there is the group of posters by Beverly Naidus’ students from the class “Art & Global Justice,” at the University of Washington, Tacoma. Here is a selection of them

Cassandra Green My Dream was an Illusion

Josephine Green Fenced In

Leni Reinwald

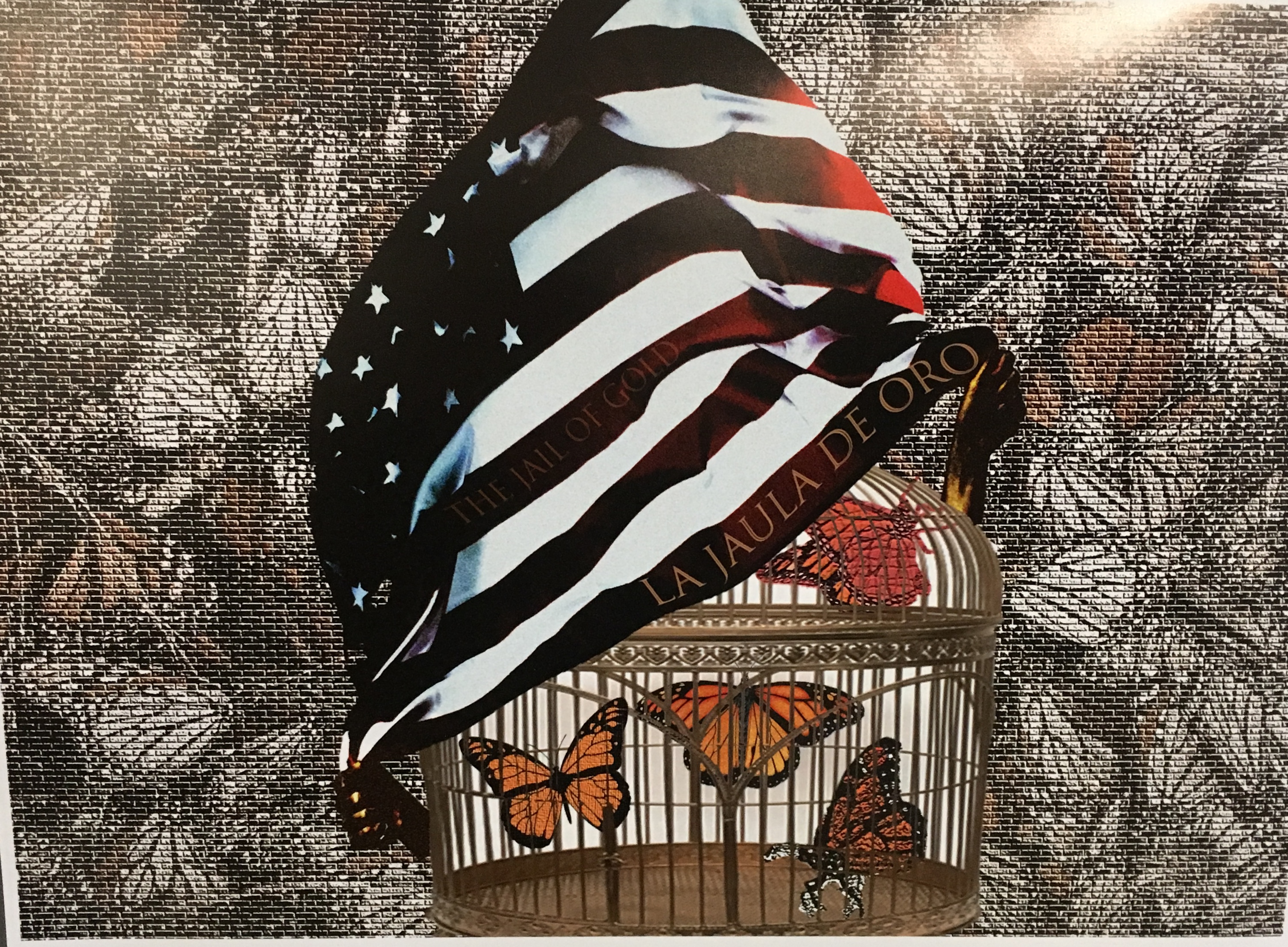

Karla Gonzalez La Jaula D’Oro

Krystal Hedrick Practice Resistance

Art and Global Justice Project artists, taught by Beverly Naidus, artist/writer/activist and associate professor of interdisciplinary arts, UW Tacoma: Diana Algomeda, Fazeema Bano, George Camacho, Emily Clouse, DA James Christian Flores, Karla Gonzalez, Cassandra Green, Josephine Green, Ryan Hanley, Krystal Hedrick, Natalie Lawrence, Wesley Scott, Carolyn Reed, Levi Reinwald

POETS MUSICIANS ACTIVISTS

July 20

Smokey Wonder, hip-hop free form DJ, Mr. Wonder seeks to unify today’s music with that of the past, creating interesting and unique sonic compositions glo’d up with scratches, beat juggling, mixing, and blending techniques to rock the party.

Ricardo Gomez, Associate Professor at the University of Washington Information School, and faculty affiliate with the Latin American & Caribbean Studies Program and the UW Center for Human Rights. He specializes in social dimensions of the use (or non-use) of communication technologies, especially in community development settings. He will be presenting selections from migration stories included in Fotohistorias, and Mi-gra-tion.

Eduardo Trujillo, passionate refugee who seeks for a way to bring peace of mind to those incarcerated and or in fear of deportation. Eduardo brings hope to people through music and spoken word.

David Garcia, artist from Walla Walla, writes multicultural poetry to express his ideas and to give hope to people.

Raúl Sanchez, bilingual poet, an interpreter, translator, a 2014 Jack Straw Fellow, Poetry on Buses judge, a TEDx participant, human rights advocate and a mentor for the PONGO program in the Seattle Juvenile Detention Center

Maiah Alicia Merino, Mexican-American Indigena writer, writes poetry, prose, short stories and plays. Maiah weaves culture, language, present and past to bring vibrant characters to life–speaking life into the shape of the stories.

Marcus Berley, poet, has written a dozen volumes of poetry, mostly in the short, simple style developed over the centuries in China and Japan. For the past 5+ years he has worked professionally as a psychotherapist, primarily with children and adolescents.

Anna Bálint, poet, is the author of Horse Thief, a collection of short fiction spanning cultures and continents and two earlier books of poetry. She recently edited Words from the Café, an anthology of writing from people in recovery.

Here is Scott Story’s vimeo about the performance evening.

August 17

Tello and the Invisibles. The new song or La Nueva Cancion, of Latin America is a musical movement that has its roots in folk music and expresses the concerns, hopes and struggles of the people. It is music with a social message. Not necessarily protest music, but music that speaks of love, hope, justice and equality. La Nueva Cancion is the voice of human rights. It is music by the people for the people.

Maru Mora Villalpando, Bellingham, Wa, Bellingham, Wa, is community organizer, founder of Latino Advocacy, member of the National Campaign Not One More Deportation and co-founder of NWDC Resistance

Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muhs, Ph.D. is the author of several collections of poetry, including the recently released The Runaway Poems, addressing the epidemic of runaway youth. The daughter of immigrant farmworkers from Durango Mexico, Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muhs has represented the United States abroad as a Chicana poet, in several countries.

Marcos Martinez is Executive Director of Casa Latina, a worker center in Seattle, WA. Casa Latina serves immigrant Latinx day laborers and domestic workers through employment, education and community organizing. Marcos formerly served as Executive Director of Entre Hermanos, a nonprofit Latino LGBTQ community. Before moving to Seattle, Marcos spent 20 years working at community radio KUNM in Albuquerque, NM.

Rocio Lopez, daughter of Angelica Guillen, is reading poetry by her mother. Angelica Guillen, Professor of Composition and Literature, Skagit Valley College: 1992-2010. Cesar Chavez Human and Civil Rights Award in 2010. Her heartfelt poetry comes from her life experiences as a campesina for 18 years, working in Skagit Valley fields while living in a migrant labor camp outside LaConner, WA and her lifelong experience as a Latina woman.

This entry was posted on July 26, 2017 and is filed under Immigration, Uncategorized.

Zhi LIN: In Search of the Lost History of Chinese Migrants and the Transcontinental Railroads

As we enter the exhibition “Zhi LIN, In Search of the Lost History of Chinese Migrants and the Transcontinental Railroads,” we face a large scale pale ink drawing of a wide railroad track that recedes rapidly into the distance in an empty, desolate landscape with the title “Golden Spike Celebrations-Chinese Workers’ Vantage Point of Andrew J. Russell’s Champagne Photo Site 2008.” Here we see the drawing with the artist posing in front of it.

In the drawing, there is no one in sight. And that of course is the point.

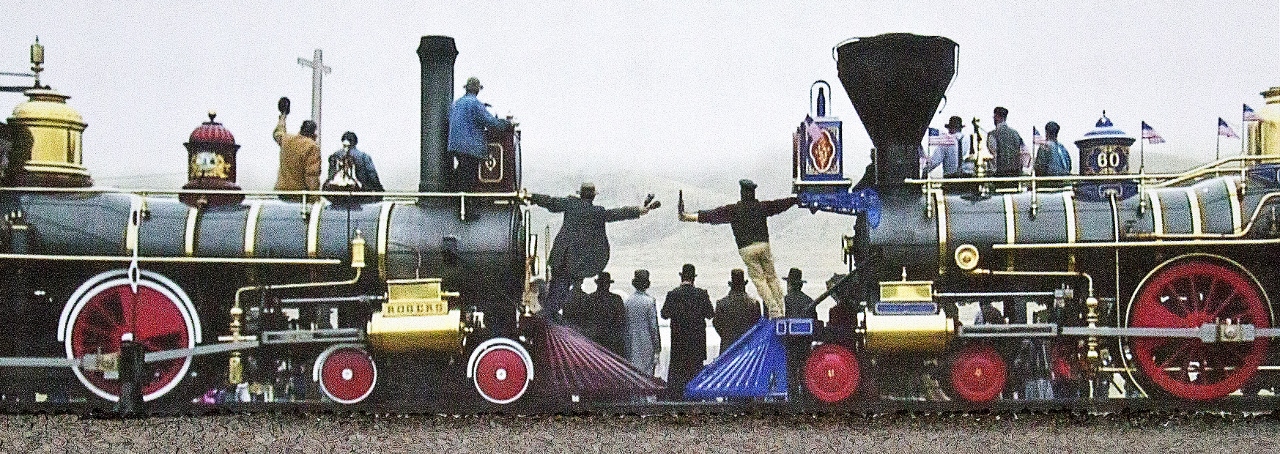

At Promontory Point Utah, on May 10, 1869, the transcontinental railroad connected the United States from one coast to the other. Andrew J. Russell memorialized the event in his iconic photograph “East Meets West at the Laying of the Last Rail.” In the photograph two engineers hang off the facing steam engines holding bottles of champagne, as the leaders of the two railroad lines shake hands.

The Chinese workers who constructed the railroad from California to Nevada are nowhere to be seen.

Every summer that event is re-enacted. Every summer the exclusion of the Chinese workers continues.

The backbreaking work by Chinese Migrants in subzero winter storms and blazing summers, hacking tunnels through solid rock in Donner Pass, working twice as fast as other workers, losing their lives in the hazardous work and through the vigilante murders of those who stayed on, all of that history had been expunged, deleted, unrecorded.

Zhi Lin, Professor of Art at the University of Washington, has spent many years unearthing scanty records and material remains, as he followed in the workers steps and empathized with their experiences.

He thought carefully how he could make their history come alive. He did not want to simply create imaginary realistic portraits. The result is this extraordinary exhibition.

“Zhi LIN, In Search of the Lost History of Chinese Migrants and the Transcontinental Railroads,” ranges from almost abstract paintings that unscroll across long walls to tiny ink drawings.

Entirely filling one wall, a video projection of a slow moving steam locomotive moves toward a facing locomotive The engines stop with enough space for two engineers to hang off the front, as they clink their bottles. But in this film, we see the engineers from the back. Zhi Lin photographed the reenactment in 2014 from behind the trains. His film has the title “ ‘Chinaman’s Chance’ on Promontory Summit: Golden Spike Celebration 12:30 PM 10th May 1869, 2014.

The engines are in the forward plane of the film space, creating the effect of sitting directly on top of the 5 tons of rock ballasts, the supports for railroad tracks. The rocks are piled on the floor of the gallery space. Looking closely at the stones, we see names written in red. They suggest a giant graveyard for the Chinese workers with the materials of the construction of the track. But the names repeat over and over. The artist wrote the few names of Chinese workers that he found in railroad pay records, but he believes even those names, supposedly of leaders of groups of workers, were actually made up nicknames.

The film lays out the facts:

“During road construction, several thousand of [the Chinese workers] were badly injured and disfigured, and at least 1,300 lost their lives. The dead were never counted, nor have they been memorialized. From shallow graves along the roadbeds, some 12,000 pounds of bones, about 1,200 workers, were gathered and shipped back to China.”

Chinese migrants, originally drawn to the US by tales of golden mountains, often ended up working in mines. Their incredible work ethic and skill soon led them to be recruited for the excruciatingly difficult job of digging tunnels through solid rock in the Sierra Nevada what Charles Crocker, an owner of the Central Pacific Railroad referred to as “bone-labor.”

Lin forced himself to re-experience the conditions of these workers by revisiting the sites of their labor in the same weather conditions in which they worked:

“I descended deep valleys and icy tunnels, crossed rivers and streams, climbed snow hills, cliffs and summits, walked on flat-burned campgrounds and along railroad tracks and paid tributes to Chinese graveyards. I made a special trip … facing the winter elements.”

His delicate ink drawings of these sites ironically adopt the romantic approach to landscape practiced in Europe. This work (above) has the title “Railway Tunnels on Donner Summit, California – A Rectification to Albert Bierstad’t Donner Lake from the Summit” ( see Bierstadt below) which romanticizes the view and obscures the tunnel.

The next chapter of the story, The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, triggered vigilantes to expel the Chinese from communities in the Northwest and California, from Tacoma in 1885, Seattle in 1886 and from hundreds of other towns where racists burned entire neighborhoods and even massacred hundreds of people.

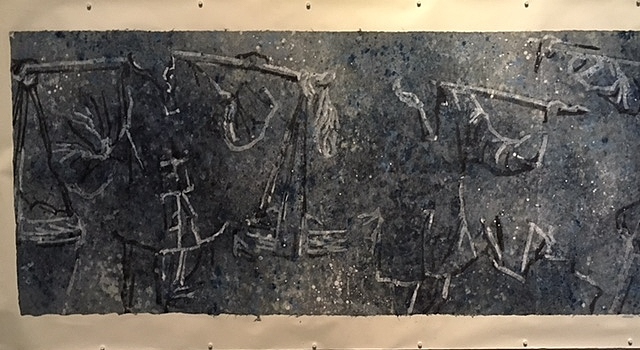

To honor these nightmarish tragedies, Lin turned to very long narrow almost abstract painting with titles like Snowstorm on the Cascade Summit Switchback” and “Sunset on Cascade” 2016. These intricate works on Chinese paper combine woodblock printing and painting; the closer we look, the more we see.

Lin anchored the abstractions with found objects and shapes as references to the vanished workers such as the frog fastenings on their jacket, or the ghostly outline of a worker carrying a pair of buckets on a long pole on his shoulders

First we see the large hieroglyphic, calligraphic drawing which suggests a figure, then the stunning gestural detail and finally the layered abstractions of the background.

First we see the large hieroglyphic, calligraphic drawing which suggests a figure, then the stunning gestural detail and finally the layered abstractions of the background.

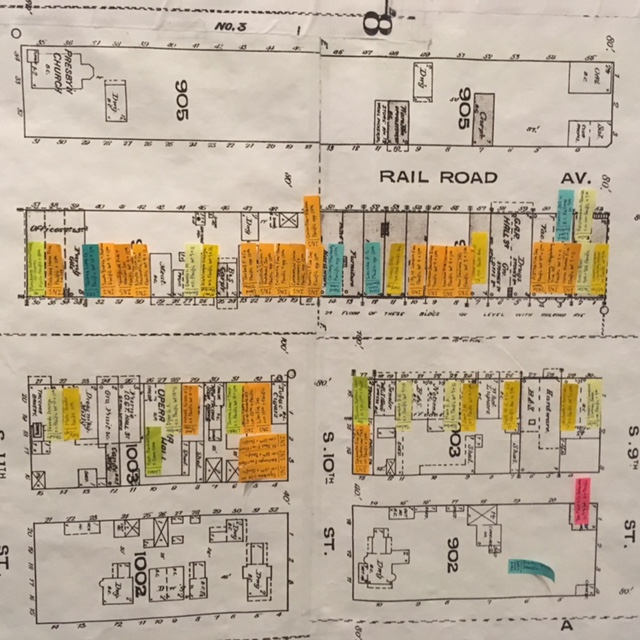

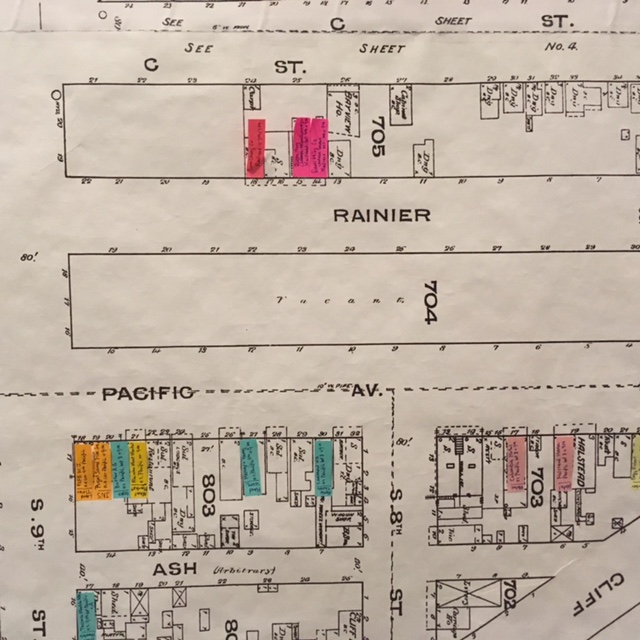

The last component of the exhibition focuses on Tacoma itself, and the horrifying expulsion of the Chinese on a cold rainy day in November of 1885, driven out by hundreds of vigilantes, armed guards, including even the Mayor.

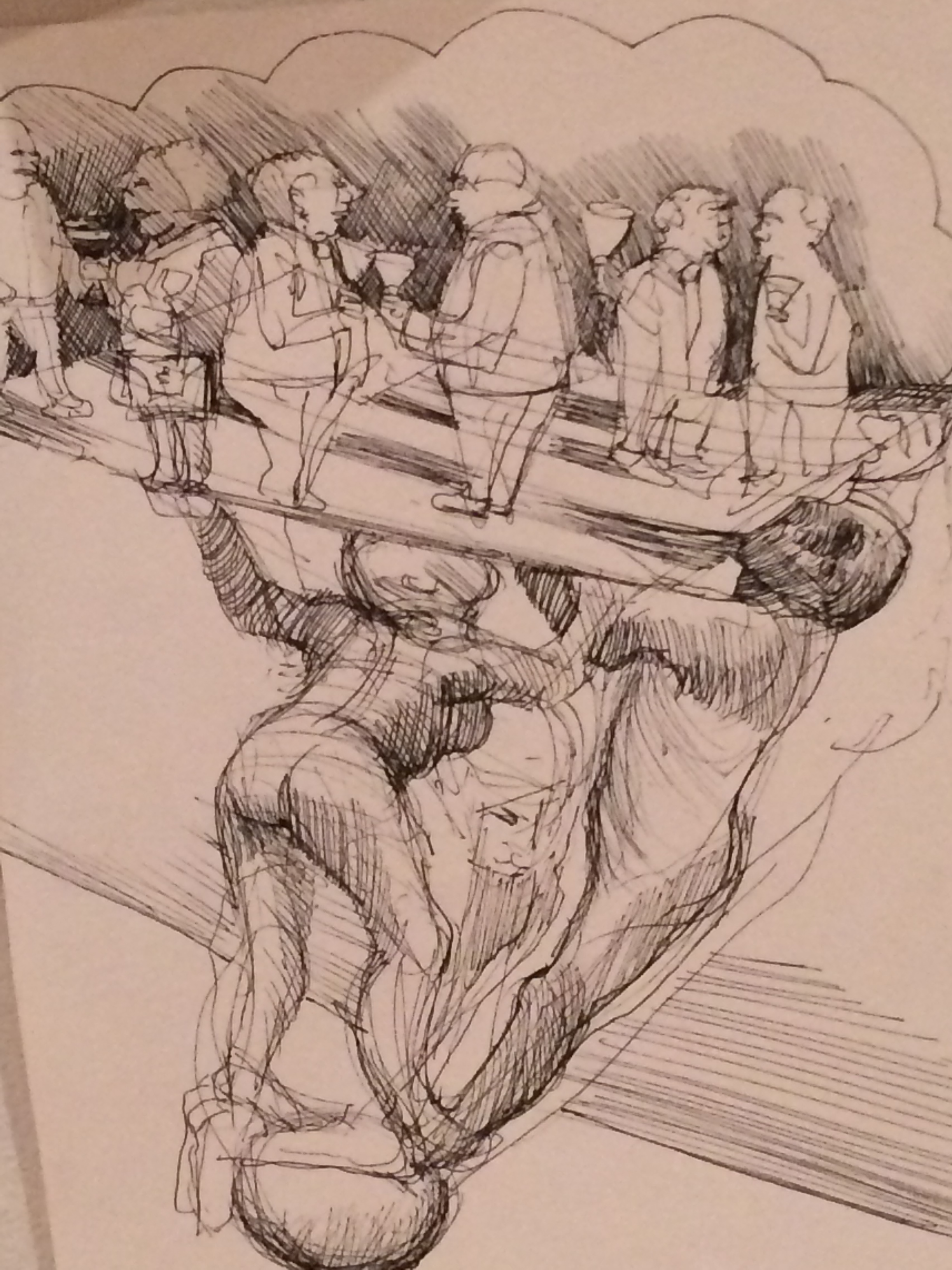

For this topic, Lin created a more traditional scroll in scale and style depicting the 197 Chinese workers, their elders and their children as they struggle down Pacific Avenue, on the way to the Lakeview Railway station.