Margaret Fuller 1810-1850-From Transcendentalist Philosopher to Investigative Journalist

**Last week, as I gazed out into the ocean at a sandbar just offshore from Point O’ Woods, Fire Island, I found it hard to believe that on July 19, 1850 Margaret Fuller, brilliant member of the Transcendentalist circle, feminist, and journalist, drowned there as her sailing ship lay aground in a raging storm.

I was standing on that beach because my brother, Alexander D. Platt, had organized Margaret Fuller Day in Point O’Woods to honor the memory of this extraordinary woman. The guest of honor was Megan Marshall who won the Pulitzer prize for her book Margaret Fuller A New American Life. In addition we heard from two speakers on “Margaret Fuller’s 1844 Journal and its Unfolding Stories,” Finally we had a lively presentation on the shipwreck itself and the shortcomings of rescue techniques in 1850.

In these presentations, Fuller emerged as a pioneering feminist, philosopher, and journalist at a time in the 1830s and 1840s when women had little freedom to speak, write, or even think for themselves.Fuller planted the seeds for radical women in Boston that led to the feminist movement in the United States which began in earnest in 1848 at Seneca Falls.

Why did she drown off the coast of Point O’Woods?? Fuller had sailed from Italy where she had been reporting on the Italian revolution (note how extraordinary that fact alone is), had fallen in love with an impoverished radical count, and had a baby out of wedlock. Fuller was a radical women who ignored social mores, believed in the equality of the sexes, and pioneered fearlessly in everything she did.

But the sailing ships of the 19th century were fragile in the face of wild storms and to be shipwrecked was usually fatal.

She, her lover (possibly her husband) and her baby all drowned in the shipwreck caused by the incompetence of a substitute captain ( the captain had died of smallpox shortly after the departure from Italy.) The ship was a sailing ship, (steamboats cost more and she was impoverished), it carried a marble statue by Hiram Powers of John Calhoun commissioned by the city of New Orleans and other marble. The marble cargo meant that the ship could not get off the sandbar where it had run aground, and it was gradually torn to pieces by a storm.

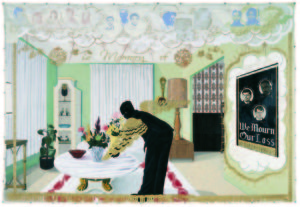

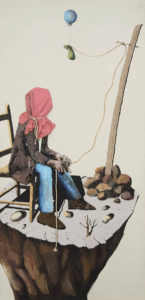

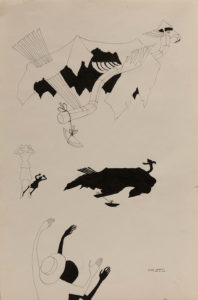

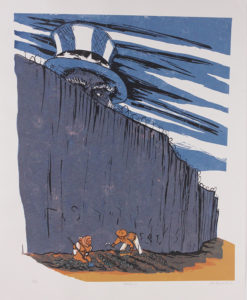

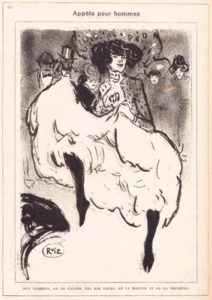

A few crew members swam ashore, the captain’s wife came ashore on a specially rigged line (as in Homer’s Life Line, a more organized version of that process) , but Fuller refused to leave the ship, her baby and her lover, she did not know how to swim. They all drowned. Meanwhile on shore scavengers ignored the stranded people and collected the ship’s cargo. At that time no manned lifeboats existed on the shore. (The image above is imaginary and apocryphal, reducing Fuller to a passive traditional woman.)

But the main story is Margaret Fuller herself and the context in which she developed. She was blunt, outspoken and brilliant at a time when few women spoke at all. Her brilliance was the direct result of her education by her father, who taught her from a precocious age, and her own self education. She went from studying Latin at the age of six to exploring conditions for women in prisons as a journalist in the 1840s.

Margaret Fuller stood out among the free thinkers who congregated in Concord Massachusetts in the late 1830s and 1840s around Ralph Waldo Emerson. She was a dazzling presence among the men of the Transcendentalist circle, all of whom, had women to support them.

Thinking it would give us insights into that Transcendentalist circle (wonderfully described in Susan Cheever’s book American Bloomsbury) my husband and I went to an exhibition at the Pierpont Morgan Library “This Ever New Self, Thoreau and His Journals.” The exhibition honors the 200th anniversary of Thoreau’s birth.

What we learned is that Thoreau is the polar opposite of Margaret Fuller, suggesting the breadth of the transcendentalist movement. He was an introvert who spent a lot of time alone, looking at nature, recording its changes, supported financially most of the time, by the money of other people, as well as in his personal needs by his mother. Fuller was an extrovert and a single woman. She had to support herself, and frequently she was supporting her family as well.

Still, before returning to Fuller, I want to mention that as a writer, I loved the Thoreau exhibition, even though he had little to do with Margaret Fuller.

The exhibition outlined his interests and his politics. Coming from an elite Harvard education, as did Emerson (but not Nathaniel Hawthorn or Bronson Alcott), Thoreau took the transcendentalist resistance to conventions the farthest, he shed all social expectations, almost all possessions, and spent much of his time observing and recording the details of the natural world. But he shared his amazing knowledge as a teacher ( Louisa May Alcott as a young girl was his pupil and had a crush on him), and, in his well known writings.

The central idea of the Transcendentalists was that nature is the source of true spirituality, more than any God constructed by organized religion. But humans fail to recognize their mystical connection to nature in their distraction with material possessions. Emerson first developed this in his essay on Nature in 1836. But Thoreau went much further in his immersion in the minutiae of nature itself. As a result of his detailed observations of birds, flowers, trees, insects and so much else, his journals are a useful reference today as climate change eliminates so many species, and the dates of seasonal blooming changes radically. (See Walden Warming, Climate Change comes to Thoreau’s woods, by Richard B Primack)

At the same time, he participated in the world. The exhibition highlighted Thoreau’s fervent defense of John Brown (an odd campaign for the peaceful men of Concord, which Susan Cheever finds horrifying and based on their naivete) , his disdain for a government that justified slavery, his assistance on the escape of slaves to Canada.

Another section addressed his knowledge of the indigenous people of Concord, the Wampanoag. He learned their language, he discovered their artifacts, he respected their beliefs. Indeed his perspective on nature is much closer to indigenous beliefs in the continuity between ourselves and the natural world, than that of the Enlightenment in which we are the conquerors of the natural world.

As a writer, I was most excited by his process: he walked about with small scraps of paper on which he made notes, he then transferred these to a journal, from that journal he excerpted for lectures, and edited sections for books. (I kept thinking of my own utterly disorganized journals that hopefully no one should or will ever read).

Although Fuller of course knew Thoreau in Concord as she spent more and more time there with Emerson, as the editor of the

literary/philosophical magazine the Dial in 1840-42, her main focus was philosophy, words, ideas, thoughts, literature, writing and above all conversation and social connections in the most positive sense of substantive friendships. She and Emerson had an intense relationship, although probably not a sexual one. ( as was also the case with Nathaniel Hawthorne).

She invited many women to contribute to the Dial, and wrote fervently on the equality of men and women ( see below).

As a critic, I particularly appreciated her writing on criticism, in this passage showing both her acerbic wit and her sharp insights: “Essays, entitled critical, are epistles addressed to the public, through which the mind of the recluse relieves itself of its impressions. . . . Or they are regular articles got up to order by the literary hack writer, for the literary mart, and the only law is to make them plausible… Critics are poets cut down, says some one–by way of jeer; but, in truth, they are men with the poetical temperament to apprehend, with the philosophical tendency to investigate”

In other words to be a good critic you need to be a philosopher, poet and observer. I like that idea.

Most of the Transcendental group were entirely broke, most of the time. Ralph Waldo Emerson, who had inherited money from a young wife who died young, supported almost everybody. Fuller edited the Dial without pay – she supported herself with occasional teaching and “conversations,” held at a bookstore run by Eliza Peabody, another feminist and first female publisher in Boston. These all female conversations among the intelligentsia of Boston became a strong foundation of the suffragette movement.

Ralph Waldo Emerson suggested that Thoreau submit a piece to the Dial. Fuller rejected it with caustic words “the thoughts seem to me so out of their natural order, that I could not read it through without pain. I never once felt myself in a stream of thought, but seem to hear the grating of tools on the mosaic. “

Fuller had to make a living, so she boldly moved on to New York City to be the first female journalist for a major newspaper, invited by Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune. She pioneered front page stories on orphan asylums and conditions in women’s prisons. She convinced the newspaper to send her to Europe to cover the 1848 uprisings there and that is how she came to be on the sailing ship Elizabeth, after reporting on the Italian revolution. Thoreau himself went to look for her lost manuscript about the Italian revolution, but he came back without it.

But in the end, going to the beach at Point O Woods, a stunning expanse of uninterrupted ocean ( very different from our rocky cliffs and steep forests here on the west coast), all I could think of was how close to shore the sailing ship went aground, only 50 meters and how incredible that Margaret Fuller and her family drowned there, with scavengers standing on the beach.

In Point O Woods, a gazebo was erected in honor of Fuller, (the dynamic women’s committee wanted a library, but the men of Point O Woods only approved a gazebo. It washed out to sea a few years later.

But there are other memorials to Margaret Fuller in Boston and Cambridge, as detailed on this blog.

Her greatest monument though is her own writing. Women of the Nineteenth Century, expanded from her 1843 essay in the Dial advocating equality of the sexes “The Great Lawsuit: Man vs Men, Woman vs Women.” She was way ahead of her time in suggesting that “there is no wholly masculine male and no purely feminine woman.” Her letters reveal her deep friendships in My Heart is a Large Kingdom, her book Summer on the Lakes in 1843 on her trip on the great lakes (going on steamers from one place to another) marks a particular time and again her perceptions are far ahead of her contemporaries.

She describes staying on Mackinaw Island where Chippewa and Ottowa tribes “are here to receive their annual payments from the American government. As their habits make travelling easy and inexpensive, neither being obliged to wait for steamboats or write to see whether hotels are full, they come hither by thousands and those thousands in families, secure of accommodation on the beach and food from the lake. ” There follows a rant on the iniquities of so called Christian traders who offer the Indians rum in order to take advantage of them.

My local public library even had Life Without and Life Within, Reviews, Narratives, Essays and Poems, published by her brother in 1895. In it I found her review of Frederick Douglass’s newly published autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass published by the Anti Slavery Office in Boston, 1845. “It is an excellent piece of writing and on that score to be prized as a specimen of the powers of the black race, which prejudice persists in disputing. We prize highly all evidence of this kind, and it is becoming more abundant.”

Fuller, like all the Transcendetalists, immersed herself in German philosophy, and classical literature, but she moved on to address the world as she saw it in the 1840s, a world of inequalities, of slavery, of exploitation. She courageously opposed in her life and in her writings, the oppressions of traditional social and religious practices and the repression of women.

I wish she were here today with her incisive writing. We need her fearless voice to address the ignorance and hypocrisy of our current leaders as they celebrate escalating oppression in the guise of “freedom.”

** I have been away from this blog since February because I had knee surgery. I am still not going to large exhibitions, but here is my modest return.

This entry was posted on June 23, 2017 and is filed under Feminism, Uncategorized.

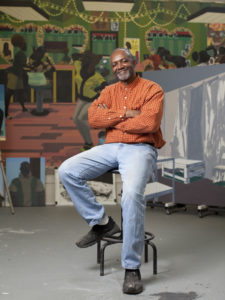

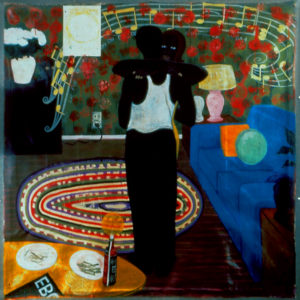

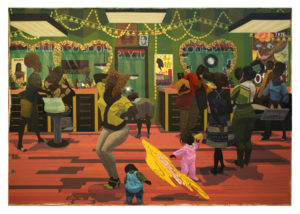

Kerry James Marshall Maestro and Shaman

Kerry James Marshall. A stunning retrospective exhibition at the Met Breuer featured room after room of his magnificent paintings, filled with magnificent people who are very black, blacker than real African Americans to the point of being confrontationally black for a white museum audience. These black people are how white people see black people, all one shade of darkness, an absence in the landscape, a trope of fear, a criminal, a threatening presence. Black person coming? Time to cross the street.

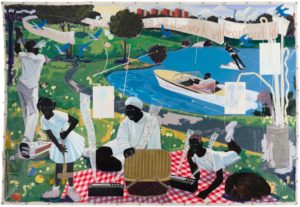

But wait. These black people are simply living their lives, they are living in the housing developments that were built to provide a utopian future for impoverished people. The developments had lawns and playgrounds. The city has public parks to play in. That was enough wasn’t it? As in my photograph taken not far from the North end of Central Park in New York City, these were “wonderful communities”. So what are these people doing?

As in my photograph taken not far from the North end of Central Park in New York City, these were “wonderful communities”. So what are these people doing?

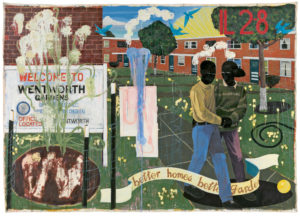

They are enjoying life, they are walking hand in hand, they are riding bicycles, they are celebrating Easter. But who are they looking at? Usually, not each other. Or if they do look at each other, their eyes also seem to look out toward us at the same time, as in the Wentworth Gardens painting “Better Homes, Better Gardens”. They seem on guard, as though these pastimes are somehow going to be taken away at any moment. They are frozen, not moving, not joyful, not relaxed. They live in the grip of a dream of life, a life free of surveillance, crime, dirt, broken elevators, overflowing washing machines, petty thieves, poverty, gangs, children who die, husbands who vanish or get shot, wives who die. No, none of those aspects of life are depicted here, but they lurk just under the surface.The surface paint patterns, suggesting overgrown flowers or fountains slightly out of control, are more like graffiti or something more generic, simple defacement.

Children have dates on them, the date of their death.

Children have dates on them, the date of their death.

Fathers dig holes – are they graves? The lid of a picnic baskets becomes a shield. These people are striving for life, they are taking what is offered as much as they can, but it can disappear any minute. And the disappearance is because of who these people are staring out at, outsiders, white people, police, drug dealers. Invisible in these paintings, next to these ordinary people trying to live their lives, are all those threats. These are Kerry James Garden Series.

Fathers dig holes – are they graves? The lid of a picnic baskets becomes a shield. These people are striving for life, they are taking what is offered as much as they can, but it can disappear any minute. And the disappearance is because of who these people are staring out at, outsiders, white people, police, drug dealers. Invisible in these paintings, next to these ordinary people trying to live their lives, are all those threats. These are Kerry James Garden Series.

In his retrospective, racism, darkness, fear, death lurks behind every single painting, sometimes obviously, sometimes more subtly. Marshall honors African American as well as white heroes, he memorializes those who have died in the cause of freedom for slaves, or former slaves. He knows his history, and he honors those who died such as the Stono Group ( a little known slave uprising in 1739)and Nat Turner, much less lionized than the white John Brown.

Nat Turner with the decapitated head of his master shakes up a white viewer. We are used to dead “others” or historic long time ago dead, but here is a white “master” from the US decapitated by an uprising slave! Wow.

Nat Turner with the decapitated head of his master shakes up a white viewer. We are used to dead “others” or historic long time ago dead, but here is a white “master” from the US decapitated by an uprising slave! Wow.

But Marshall confronts other prejudices. He gives us love. We white people do not think of African Americans as enjoying love amongst themselves because we are obsessed with their sexuality as a threat to us. The black white divide has always “swung” on that fear. Marshall not only gives us loving couples, he gives us eroticism, black naked women and men, he gives us romance.

Last he gives us art, he gives us art history, he brilliantly quotes our most famous historical icons, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Edouard Manet, Diego Velazquez, not to mention more recent artists. He quotes styles, plays with decoration, minimalism, text, staging. Much is made of his painting in the catalog for the Breuer exhibition. On and on they write about the paint, the paint, the paint. And the art historical references, and the contemporary references, almost always to white artists, as though that will legitimize the work.

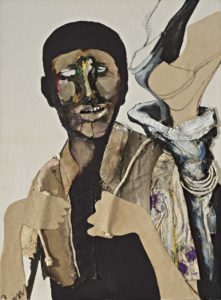

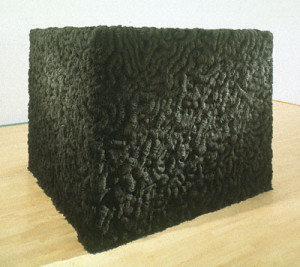

But the central theme of Marshall is to correct an absence. Absence of the black body as subject, as human, as living, as romantic, in the history of art, in museums, in our lives. And the underlying sea of references, about which we could go on layering ideas all day, are the celebration of African religions, mysteries, symbolism, right on equal footing with all those nice white guy quotes. The integration of these two worlds is what Marshall seeks. ( This is the only mystical work included in our press images)

Part II

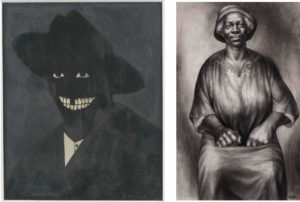

It was absolutely amazing to me that all the experts writing repeatedly in the catalog about the importance of A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self 1980 never mentioned that it gives back to the white gaze what we see as white people, which is caricature, shadow, teeth, eyes. That is the reason for the title.

We do not see the person, the humanity, the complexity, the dignity (as suggested in the Charles White painting above, Marshall’s most important mentor).

The painting is significant not as a portrait, but as a manifesto, an absolute expose of prejudice. Marshall’s black on black paintings of “invisible man” based on the Ralph Ellison book as he has said repeatedly, emphasize that inability of white people to see black at all as anything other than one single dark place. But as you look harder into these paintings many details emerge, subtleties, nuances. That is what we white people all need to do. (Notably our press packet included not a single one, the self portrait came from the internet)

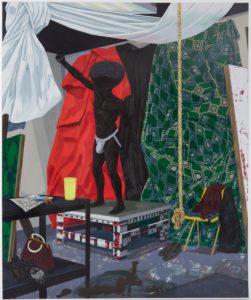

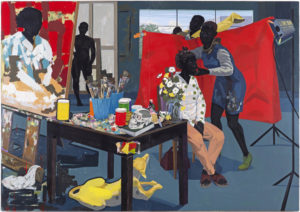

In Untitled (Studio), as Helen Molesworth points out, the artist is absent. The models are present, the act of making art is present. The wonderful vocabulary of references and styles is present.

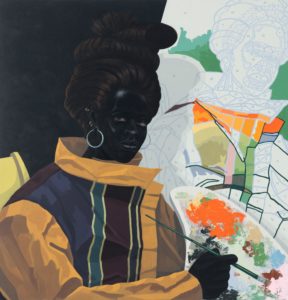

The artist is present in the “untitled” portraits of artists, but again we see the caricature of white prejudice, the traditional portrait format is exaggerated, large torso, direct gaze, holding a giant palette, an irrefutable presence; but behind lurks a paint by numbers canvas. If we cannot see humanity in African Americans, we cannot see the enormous subtlety of their art either. So he gives us the artists and the paint itself, because we can understand that (and understand we do, endlessly reveling in those piles of paint on the palettes, wow, look, see, paint). And of course the artist had a lot of fun painting these works as well.

The artist is present in the “untitled” portraits of artists, but again we see the caricature of white prejudice, the traditional portrait format is exaggerated, large torso, direct gaze, holding a giant palette, an irrefutable presence; but behind lurks a paint by numbers canvas. If we cannot see humanity in African Americans, we cannot see the enormous subtlety of their art either. So he gives us the artists and the paint itself, because we can understand that (and understand we do, endlessly reveling in those piles of paint on the palettes, wow, look, see, paint). And of course the artist had a lot of fun painting these works as well.

Marshall is a subtle, brilliant trickster. He has duped white eyes into looking at our own fears of darkness, with stunning paintings that elevate the humanity of the African American experience for us to see, embedded in delicious colors, textures and drawings, dizzying arrays of styles, all of it simply at the service of seducing us into actually seeing that African Americans are real people.

That is why Marshall is unique. Dozens of African American artists have presented African Americans in film, photography, painting, sculpture ( as seen for example in the 1994 exhibition “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art”. The Whitney held it just before Marshall emerged in the late 1990s. The work is subtle and sophisticated, in some cases, perhaps we can say it is cloaked, as in the work of Lorna Simpson for example, with all those backs and fragments, no faces.

But to what extent did white eyes face their own prejudices in looking at that work. Not at all. In fact often our expectations were reinforced when we saw criminals or large black sexual organs.

Marshall leads us in through art history. He allows us to wallow in our old fashioned, comfortable modernist references. Look, there is Manet’s cat, or there is a skull out of Holbein!!! Flat paint samples play with space!!! But as we wander through these references, we cannot avoid the people, the life, the layers of experiences

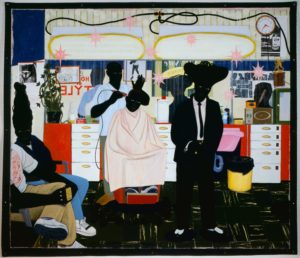

For that reason, certainly, the two paintings of the beauty parlors: De Style 1993 and School of Beauty, School of Culture 2012 are the greatest gifts that Marshall has given us. They allow us white people into a place that is almost a sanctuary of black power, on a par with church (which he does not represent, although spirituality appears often). And as we roam through it, we white people suddenly realize we have never been here before, and we actually do not belong here. But we can acknowledge that here is real life, real culture, real people. And it is the white ideal that in the end is a mirage, an odd phenomenon, as the small children point out in School of Beauty. Here people really are living their lives on their own terms. No one looks out.

This entry was posted on March 1, 2017 and is filed under African American history, American Art, Art and Activism, art criticism, Art of Democracy, Black Art, Black Panthers, Ethnicity, Uncategorized.

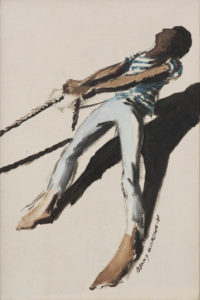

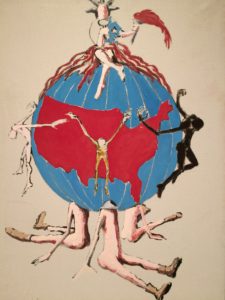

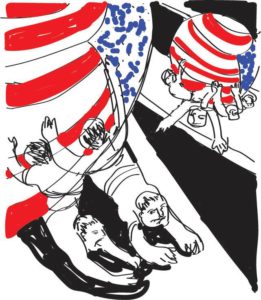

Benny Andrews: The Bicentennial Series predicts America Today *

Liberty ( Study for Trash no. 6) 1971 oil on canvas on painted fabric 78 x 39 3/4

In one of the most potent images in Benny Andrews Bicentennial Series from the 1970s, the Statue of Liberty sucks a lollipop as she sits on top of the stump of a dead tree. Naked men wearing only an army helmet and boots support the stump on a wagon.

Trash, the mural, in collection of Studio Museum, Harlem

In a final full scale mural, Liberty leads a succession of carts, one carrying a “war bitch,” as the artist describes her, and another, a giant penis topped by flowers.

Puller ( Trash Study no. 1,) 1971 oil on linen, 18 x 11 7/8″

Several men, one of them a convict in chains, strain to carry everything off to the garbage dump “Trash,” is one in a series of murals by Benny Andrews painted during the years leading up to the Bicentennial in the early 1970s. His dark vision could have been painted yesterday.

On seeing excerpts from his Bicentennial series at the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in January, I was stunned with the forcefulness of his comments on the abuses of our American institutions. Today, as we struggle against the escalating wave of white supremacist policies from Washington, D.C., they speak to us directly.

During the early 1970s Benny Andrews created BIG paintings as he put it, to provide his own perspective on the 200th anniversary of the Nation. BIG because the mainstream white artists at that time were working big, and he believed his work would stand beside them. He saw that preparations for the Bicentennial were devolving into clichés for African Americans like slave cabins, and great people, he knew there was more to the story than that.

He himself had grown up in a sharecropping family, picking cotton, and he followed an incredible journey, with the support of his family, to become a trained artist based in New York City. But he never forgot his roots in Georgia, the people he knew from his childhood, the strength of the people around him, their creativity, and their perseverance.

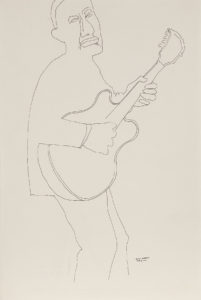

The vivid series of paintings, drawings, small studies and large works include six themes: Symbols (1970), Trash (1971), Circle (1972), Sexism (1973-74, War (1974),Utopia (1975).

Strummer (Study for Symbols), 1970 india ink on paper 18″ x 12″

His first large work, “Symbols,” paid homage to his roots. In the recent exhibition, we saw drawings for the large finished work now in the collection of the Ulrich Museum at Wichita State University. His spare linear style is as elegant as Ingres. For this first work, he went back to Georgia and sketched his home, his family, a bride and groom, musicians, and in the center of “tree of life.” It appears to be children playing in the tree, but it also seems to be people “hanging” from the tree, clearly a reference to lynching. Nearby two people carry off a dead child.

Since Andrews family has mixed black and white heritage, but all were considered African American, he frequently suggested racial mixing. Even people who are white in his paintings reference his African American community in Georgia. The artist pairs ordinary life, ordinary people, and nightmarish events; a semi-white man sits in judgement in the final “Symbols” mural, on the right. Andrews may be referring to an overseer, or a mixed race business man, his ambiguity is intentional.

He worked in dozens of separate sketches that he then puts together in a larger composition based on multiple panels. In “Symbols,” the space is complex as the imagery pushes forward or recedes into the background, based on strong diagonals that terminate at a tree in the center. In later murals his figures seem to float in an indeterminate space, sometimes framed by viewers, or encircled by odd faceless people.

Collection Studio Museum Harlem Photo: Adam Reich

Trash(1971) is full of anger and sarcasm. He painted it during the Attica prison uprising. By this time Andrews had already founded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, demanding Black curators and artists in New York Museums, but more important than that, he founded the first prison art program in the country. He was outraged at the failure of American institutions and Trash hauls them off to the junkheap, pulled by both a prisoner and another black man.

Liberty ( Trash Study no. 2) oil on linen 32 x22″

In the exhibition two studies presented just the Statue of Liberty, as she is disintegrating, in one (Study no 2 for Trash) she sits on top of a globe with the USA facing out, black and white people reaching out to encircle it and underneath propping it up are again the naked military indicated with hats and boots. These self sufficient paintings stand on their own. Also in the exhibition was “the Puller” the man hauling the trash wagon with the Statue of Liberty, braced against the weight. Behind him a black shadow echoes his silhouette.

Composition #9 for Trash, 1971 india ink on paper 24″ x 18″ /

Use of shadows is a crucial device in Andrews, they reinforce his imagery, creating a shadow layer, much as blacks experience their lives in a white world.

oil on twelve linen canvases with painted fabric and mixed media collage 120″ x 288″

Circle Study no 33 1972 india ink on paper 12×18″

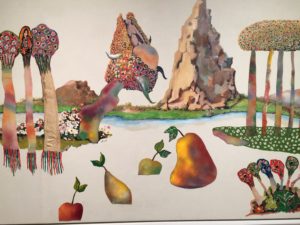

The mural “Circle” , the only one included in the exhibition, fills one wall of the gallery. Sketches and smaller paintings fill the walls nearby. “Circle” focuses on a bed on which a black/white person sits impaled, his heart carved out and rising above him as a watermelon lifted by an odd pipe like shape (in earlier sketches it was a stove).

Around this tragic figure stand a circle of people both black and white who shake their fists, look horrified, or sit passively in chairs, as the torture unfolds before their eyes.

Tied and helpless, the man on the bed reminds us today of torture inflicted on prisoners in detention, but here the reference is certainly to the tortures of simply living in the US as a dark skinned man. Andrews is the visual partner to James Baldwin who lays bare with words the torture and injustice of living in the US for people of African descent.

Andrews uses fabrics glued directly on the canvas. Thus the bed is stained and dirty made with old cloth, the head is bandaged in an actual sheet/bandage, a dirty cloth wrapped around his genitals like a diaper. That physicality paired with fantastic imagery, a personal surrealism, that relies on the grotesque to warn us of dark realities, penetrates our hearts; the physical additions to the canvas, assembled from found objects and discarded dirty materials, strike into our eyes and into our souls, they rudely speak of poverty, of suffering.

Sexism Study no 24 1973 oil on canvas with painted fabric collage and rope 96 x 50 1/2″

Another work in the cycle “Sexism” appears in the exhibition with several large works. At the entrance to the exhibition we are immediately confronted by a figure covered in a tent like sheet. She appears to be rising from a bed, but she is still caught in the strings held down by odd detritus.

Sexism Study no 8 1973 oil on linen 24 x 22″

Another strange work Sexism Study no 8 appears to be a penis man holding an instrument of torture and wearing strange clawlike shoes. He looks like a rapist with primitive tools. This particular image did not appear in the final large mural

War Study no 3 1974 oil on two stretched linen panels with painted fabric collage 35 x 49 x 1″

War Study no 1, 1974oil and graphite with painted fabric collage 34 x 25 x 1 1/4″

“War” for which a large work was never completed, is featured in two poignant collage paintings, one with a young man dragging a dead body. In “Poverty,” a man with a pink bag tied over his head suggests torture and the impossibility of escape.

Poverty Study no 1-a for War 1974 oil on linen with painted fabric collage with rope 100 x 48 x 2″

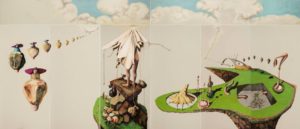

Finally, Andrews created “Utopia”, but because he could see no redeeming feature in humans, he created a fantasy landscape without any people.

Utopia Study no. 8, 1975, oil on linen with painted fabric collage 40 x 60″

Along with his very large mural scale works, and his smaller collage paintings, Andrews draws, and draws and draws.

In this exhibition, these delicate linear studies for the larger works populated by strange creatures or bizarre settings, create a constant dialogue for us with the final murals giving us insight into his thinking. Frequently, he includes shadows for his outlined figures, suggesting even in the briefest encounter with paper, the shadow world still haunts his every move and that of every person of color.

“Surrealism can get out hand real fast, but then the black experience is so ridiculous that surrealism is the best way to express it. I’ve seen the same kind of work coming from prison artists. To get through an oppressive real life, the artists have to live a fantasy life. ”

— Benny Andrews

With the draconian new immigration expulsions declared by a president who has no restraints, the dark shadows are following every vulnerable person, whether they be transgender, disabled, young, old, latino, African American, Asian, Muslim, homeless or poor.

- all works Credit Line: Estate of Benny Andrews/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

- “America Today” is the title of a mural cycle by Thomas Hart Benton painted in 1929 including both the roaring 20s and references to the poverty of the Depression. It makes a telling comparison to Andrews work in its exuberance and celebratory atmosphere that features workers of all types.

This entry was posted on February 24, 2017 and is filed under African American fiction, Arican American history, Art and Activism, Art of Democracy, Black Art, Black HIstory Month, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.

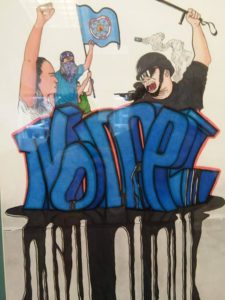

The Spirit of Standing Rock

On the second night of our cross country train trip, we passed through Minot, North Dakota. It was minus fifteen degrees. That is about two hundred miles north of Standing Rock and the ongoing resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) still continuing in sub zero weather and blizzards. Now we have the escalation of tensions with the illegal orders coming from the White House. There is a renewed call to Activists to return to Standing Rock

Activism by artists is crucial to continue to highlight the situation.

Right before I left Seattle, I attended two exhibitions supporting the DAPL resistance. The resistance is encouraging a surge in contemporary native art and exhibitions supporting Standing Rock. In Seattle we also built eighty winter shelters known as “tarpees,” tepee-shaped but covered with heavy duty poly wrap and large enough to hold stoves with a long stove pipe going through the roof.

They were designed by Paul Che oke’ ten Wagner, the famous flutist who explained his name as “of a feeling to watch over, to care for the people and things that you love for many seasons.” Paul has been an inspiring and generous spiritual leader in Seattle at every DAPL march and demonstration. Now he is also an architect. He is combining contemporary materials and traditional structures to create an entirely new type of tepee.

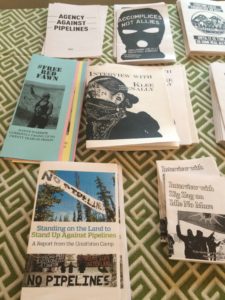

A fundraiser for the “water protectors,” at the new Sacred Hoop Cooperative Gallery at 55 Bell Street included ceramics, posters, beadwork, paintings, masks and graphic art. One whole table was filled with writings about Standing Rock, poetry, and graphic books that dramatically told the story of the conflicts of whites and natives over several centuries.

But primarily, the event was about story telling by those who had just returned from Standing Rock. It continued for eight hours!. While I was there, the story being told was both personal and mythic, the storyteller, a large man who declared he was like a bear, had just returned from Standing Rock. He told of the spirit of shared purpose. In spite of the freezing temperatures, he gave away his warm coat and then nearly froze himself. Then he told a mythic tale from the time when “humans had stopped listening” to nature and the animals stopped listening to each other. The story was punctuated with powerful drum beats that were both part of the story and kept us listening.

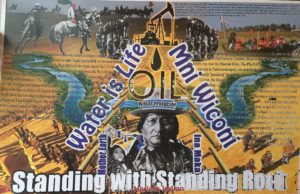

At Sacred Hoop, Robert “Running Fisher” Upham aka “Harlem Indian” honored the theme of “water is life/ Mní Wi with a large collage that included the history of the Sioux Indians as text in the background. This artist has also revived Indian Ledger drawings, the first descriptive images made by Indians in captivity in the 19th century.

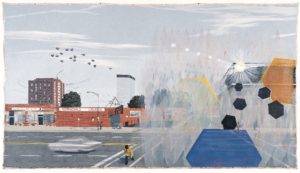

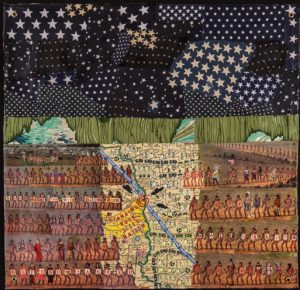

Seattle Theater Group and John Feoderov, another Seattle based Native artist, organized a one night exhibition benefit for the Water Protector Legal Collective, the on-the-ground legal support team for Standing Rock. Both Native and non-Native artists from around the country exhibited artworks that addressed environmental issues and “connections between land, culture and identity.” One of the works above by Deborah Faye Lawrence dramatically pinpointed the location of the protests in a collage.

“Protect the Sacred,“ a stunning and complex exhibition curated by Asia Tail (see image at top of post) at the Spaceworks Gallery open until February 16. (950 Pacific Ave. (Entrance on 11th St.)Mon – Fri / 1pm – 5pm, Third Thursday open until 9pm.) Tail, formerly on the staff of the Tacoma Art Museum, chose a cross section of 26 well-known and young Native artists to participate. She told me that hundreds of tribal affiliations were represented in the Seattle to Portland corridor, from the period of terminations, 1953-68 when the government took over valuable tribal land, and natives moved to urban areas. She herself is from an Oklahoma tribe.

![]()

Tail chose to focus on painting, sculpture, photography and installation. As we entered the door a large banner by Kaila Farrell-Smith” greeted us. A contrast to “Harlem Indian’s more realistic and text based homage, Farrell- Smith Mní Wičoní Banner, combines references to abstract basket patterns, and a political call to action “I explore the space that exists in-between the Indigenous and western worlds, examining cultural interpretations of aesthetics, symbols, and place. It is in this space I search for my visual language: violent, beautiful, and complicated marks that express my contemporary Indigenous identity.”

To some extent this idea permeates the entire exhibition. In work after work we see artists negotiating between native historical references and styles and contemporary approaches and content.

In the gallery, the photographs of Matika Wilbur, just back from Standing Rock, greets us first. Her subtle photographs always resonate with modernism combined with historical and Indigenous references, here in the hands of “Miss Helen, Last Carrier of the Lovelock Paiute Language,” 2016 we see a moving portrait as well as an homage.

Facing Wilbur’s photographs are two realistic watercolors by Yatika Starr-Fields. The artist usually paints intensely colored abstraction, but the impact of joining the protest at Standing Rock led him to record what he was actually seeing and provide a detailed description of the experience. “At the time this was painted, these two tipis were the northernmost structures in the whole Oceti Sakowin encampment. That day the air was alive with anticipation, and the scent of campfire smoke and sounds of all kinds echoed throughout the camp. With the setting sun casting its radiance on the changing colors of the distant fall trees and surrounding plains, the Missouri river seemingly created its own dominant horizon between past and present. This sacred hill – where burial grounds are present, and where many actions, prayers, and ceremonies take place – has been reclaimed as our own.”

Sara Stiestreem conceptual work celebrates rituals of basket weaving with rows of red circles and photographs of her hands in various specific actions. Fox Spears colorful abstractions could have been done by a white artist in the 1960s, but they are based on ancient basket patterns.

Marvin Oliver’s elegant work combines the best of native and contemporary expression

Erin Genia creates highly original ceramic sculptures with hard core messages like Facing/Not Facing: Toxic Devastation From Oil, just above) or Mobile Spill Response (top images) and finally, not illustrated, (Mni Wiconi: Water is Life Oil is Death.

Next to Genia is the work of Samuel Genia, her fifteen year old son with a bold graphic statement.

Ryan! Feddersen’s interactive globe Micro Spill, plays on the idea of a snow globe, but when we pick it up we discover it has black magnetic particles that roll around, making a clear point about the despoliation of the land by industry.

I can’t enumerate all of the works. Suffice it to say that the exhibition takes time because it encompasses so many styles and ideas. Not all the artists specifically address the issues of extraction or its transportation. But they all tell us that contemporary native art is flourishing and provocative. All of the works are on sale and a percentage of the sale goes to support the DAPL resistance. This resistance will continue, as the bringing of our dreadful new President will only make the need for Standing with Standing Rock, and all other resistance to fossil fuel extraction and transportation absolutely crucial.

As the story teller at the Sacred Hoop gallery put it. “Stories Heal. Find your standing rock and pull yourself together.”

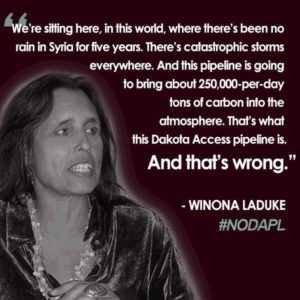

And let us give Winona La Duke the final word.

This entry was posted on February 14, 2017 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Contemporary Indigenous Art, Culture and Human rights, Deborah Lawrence, Standing Rock, Uncategorized.

Maria De Los Angeles: Artist, Activist, Undocumented

The millions of people who turned out for the world wide Women’s March to protest the new administration and make a plan of action was a spectacular and inspiring event. I joined my two brothers for the huge rally on the Boston Commons, with its history as the birthplace of the American Revolution, center of the abolition movement, point of departure for Freedom Riders, and an ideal place for hundreds of thousands of people to gather.

The millions of people who turned out for the world wide Women’s March to protest the new administration and make a plan of action was a spectacular and inspiring event. I joined my two brothers for the huge rally on the Boston Commons, with its history as the birthplace of the American Revolution, center of the abolition movement, point of departure for Freedom Riders, and an ideal place for hundreds of thousands of people to gather.

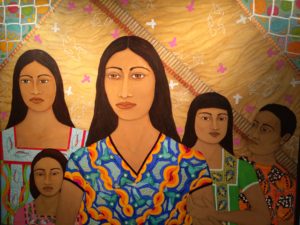

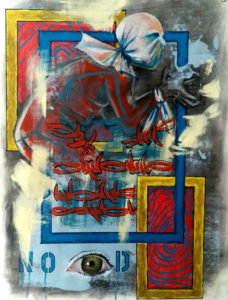

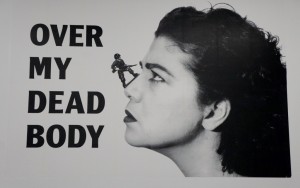

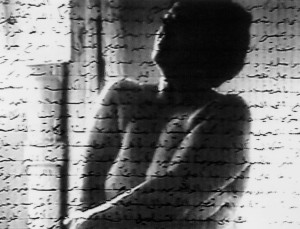

But the inspiration and urgency of the speeches by politicians, Native Americans, Muslim activists, union workers, Planned Parenthood defenders, NAACP, youth with disabilities and LGBTQ, was poignantly underscored by two meetings with Maria de Los Angeles, an extraordinary artist who is among the group of people most vulnerable under the new administration, those youth known as DACA, (Delayed Action for Childhood Arrival I explain it below). See the image at the top of the post, of the young woman surrounded by the anxieties of the situation.

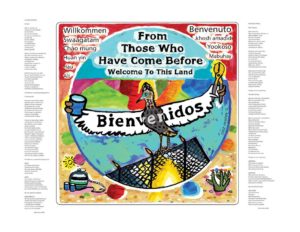

I first met Maria de Los Angeles through “We make America” an informal group of artists making 100 Statues of Liberty in mourning, with tunic, torch and crown for the Women’s March in Washington, D.C. and New York City. The day after the election, she and Joyce Kozloff, (for whom she was working and who has a long history of art activism) called a meeting to decide what to do to build community and respond to the election as artists.

The result was “We Make America”, a title which suggests that we all contribute to what America is today. The verb “make” can also literally refer to contributions of workers, immigrants, and the act of making things. Perfect. The group started small, then ballooned when it was put on Facebook the next day.

When I went to photograph the making of the props for the Women’s March, Joyce pointed me to Maria as a primary organizer.

Maria told me immediately that she is a one of the thousands of DACA, young people and twenty somethings who came here without papers as children and were given status under Obama to go to school and work legally. They are extremely vulnerable to losing that status any minute under the current administration.

Maria de Los Angeles was born in Mexico and came to California with her parents at the age of 11, growing up in Santa Rosa California. She went to Pratt on a fifty percent scholarship. Since she could not get loans as a DACA, she managed to fundraise the rest of it (these schools are insanely expensive). Then she got a full scholarship to Yale, where the professors encouraged her to question who she was and discover what she wanted to say. She talked about how difficult it was to find her voice in the midst of the fashionable “identity politics” that pigeonholed her as a successor to Frida Kahlo, dismissed her affinity with German Expressionism.

But she asserted herself and succeeded in finding her voice. Apparently there were about ten students of color in her class of 100, and most of them didn’t want to be pigeonholed or talk about race.

Last summer Pratt, where she now teaches, invited her to teach a course in Italy, giving her the opportunity to see the murals of Tintoretto in Venice, as well as the whole sweep of Italian Renaissance Art. The huge floating figures of Chagall in Lincoln Center also inspire her, as well as Siqueiros, the most radical of the Mexican muralists, who successfully paired radical politics with experimental media. I immediately saw her connection to Kathe Kollwitz, as an outspoken radical and a women addressing oppression expressed through dynamic linear drawings.

I recently saw an installation of her drawings and watercolors at Museo del Barrio where she is an artist in residence until the end of this week (January 28).

She draws with ink or watercolor on two types of paper, printmaking (which is manila) and drawing paper (which is white). In some works she draws figures on the lighter drawing paper, cuts them out and glues them onto the manila paper on which she also draws. The two tones create a dynamic that reinforces the primary theme of her work, the confrontation between ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) officials and Latinos, the threat of a home raid, a work raid, a traffic stop, leading to detention and deportation, the constant terror of a family being torn apart.

But it is not a simplistic formula. Not all of the white people are cut out with white paper or all the Latinos in manila. That is of course because that is true in real life. In fact some ICE officials are Latinos (as seen in the Alex Rivera film, El Hielo), some Latinos are white skinned (as Maria herself). ( see also Alex Rivera’s other films and projects here)

But the two colors of paper create a tension, emphasize the sense of confrontation because of the fear and hostility that is escalating every day.

Sometimes there is also text, tiny words like “My America” “Our America” emerge in bubbles from the mouths of agents, or longer texts written around the edge of the drawing are filled with the racist taunts and the clichés of white people who fear immigrants.

Some of the works are purely drawing, some watercolors, some cartoon like. Some combine watercolor and drawing. Maria de los Angeles breaks through restrictions, and conventions, just as she would like to see the barriers between races break down.

A frequent motif is ICE agents swooping down from the sky on families trying to protect themselves. Families are represented by islands of emotional lines that suggests anguish, terror, and self-protection.

But sometimes salvation itself swoops down from the sky, to rescue someone from the agents on the ground.

Most of the drawings that I saw were created before the election. That means de Los Angeles has been making visible the ongoing tensions in the Latino community for a long time.

Another theme honors the almost invisible contributions of workers. That format depicts a group of workers, holding up the white world of privilege often precariously. In a You Tube interview she also spoke of all oppressions, she does not limit her activism to only immigration, she referred to the whole range of concerns we have today.

Maria de los Angeles also creates garments. She sews paper together, and paints them with confrontational slogans, such as “illegal” and “undocumented.”, then with friends does interventions, such as recent action at a Trump hotel. She boldly speaks to media about her status, and her fears for her own future and those of so many others.

She held up the heavy corrugated cardboard torch of the Statue of Liberty for eight hours during the women’s march in New York City, leading the contingent of “We Make America”.

Pay attention to what happens in the next week or so with the Immigration regulations. Protest any reversal of the small reforms, such as DACA, enacted by the Obama administration. As someone who has been following immigration issues for several years, I have been horrified by his huge number of deportations and detentions which includes putting families and children in detention. They were horrendous, but unfortunately the terrible procedures and facilities already in place are now going to get much worse. Research the facts on detention at the excellent Detention Watch Network and Not One More Deportation.

Maria de los Angeles is a courageous person. She has chosen to express the dark fears and nightmares of Latinos in her drawing as well as to publicly speak about her status. I don’t know of any other artist who has done so much work on this subject.

Now she wants to network with other artists, as well as the general public, to encourage them to understand the complexity of the immigration system, the impossibility of being documented as an undocumented person, and the possibilities for art to address these subjects. She sees art as a powerful tool that for her must bridge the huge gap between her background and the “art world.” Her public interventions are one type of bridge. Joining with others is another.

She is hoping that “We Make America” as a collaboration of activist artists will continue to produce art about immigration. The Statue of Liberty is our most public immigration statement, together with its famous poem by Emma Lazarus ( who spent her life fighting anti Semitism and supporting immigration before she died at the age of 28). It is as crucial today as it was when it was created.

This entry was posted on January 24, 2017 and is filed under art criticism, Art of Democracy, Feminism, Immigration, Uncategorized.

The Artnauts: A Global Collective of Artists for Peace

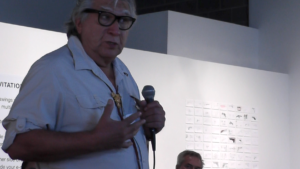

I recently met the “Artnauts” a collective of about 20 artists led by the dynamic George Rivera, a Professor of Art at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Here you see him in the front and center of the members of the group who participated in their 20th anniversary celebration.

The Artnauts have been traveling the world since 1995, going to zones of conflict and offering art, communication, dialog, and mutual understanding. In their words: “The collective uses the arts as a tool for addressing global issues while connecting artists from around the world.” They have created exhibitions with local artists in Palestine, Bosnia, the Amazon, Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, South Africa, Russia, China and many more. As they go to these places, they are also immeasurably enriched by the experience.

I was honored to be invited to speak at their anniversary exhibition at Red Line Gallery in Denver, Colorado.

Art and Social Change Land Culture and Memory Palestine 2008 and Signs of Globalization Guatemala 2009

The anniversary exhibition highlighted ten of their more recent exhibitions. These featured small works that could easily be transported.

Above you see two themes that are repeated, the ongoing Palestinian crisis and the impact of climate change and globalization on indigenous cultures in Central and Latin America.

For many years George Rivera carried huge boxes with large prints to venues around the world.

Identity Place and Memory Colombia 2015 and Diasporas of Being, Palestine 2015

Art and Ecology Guatemala 2009 Centers and Borders, China 2007 The Ecological Imperative Chile 2013 Art and Displacement Palestine 2011

An exhibition devoted to the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish 2014

Post Tractatus :Art in the Amazon 2008

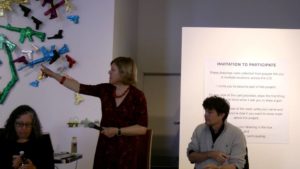

In addition to the commemorative exhibitions, Linda Weintraub was invited to curate a special exhibition of new works by some of the Artnauts, “Rally ‘Round the Flag of Justice ” Here she is speaking about the exhibition (in front of a different exhibition about guns)

All of the works are critiques, with the flag as an abstraction, a metaphor, a source of irony. Of course, we immediately think of the US flag as the subject, but there were many types of flags.

For example, Trine Bumuller, inspired by her Artnaut exhibition in Sarejevo last winter, created a tent like shape with Tibetan  prayer flags to honor the nightmare of the Bosnians; on the flags she painted the image of the Sarajevo roses superimposed on photographs of the still visible ruins of the city or other images. Red “Sarejevo roses” were painted on sidewalks where sniper’s bullets landed.

prayer flags to honor the nightmare of the Bosnians; on the flags she painted the image of the Sarajevo roses superimposed on photographs of the still visible ruins of the city or other images. Red “Sarejevo roses” were painted on sidewalks where sniper’s bullets landed.

Andrew Connelly featured a queen size bed with the US and Israeli flags sewn together, “in bed together” and under the transparent sheet we could see the Palestinian flag barely visible.

The group has visited Palestine many times, and collaborated with Palestinian artists, most recently this summer in “Art and Resistance,” an exhibition for which I wrote a catalog essay.

Here we see George Rivera in front of his piece on Palestine/Juarez, with rubber bullets and a water bottle signifying the two borders.

He pointed out that the red triangle on the flag also signifies the wall on the two borders.

At the symposium accompanying the exhibition he said (on November 11, only three days after our “election”)

At the symposium accompanying the exhibition he said (on November 11, only three days after our “election”)

“In spite of what we have become on Tuesday, around the world, they love us a human beings. The Artnauts affirm in this time people who stand up to injustice. “

He spoke of his own personal motivations for creating a collective that would stand up to injustice.

“I came out of intense racism in a small town in Texas. Art is a tool for addressing global issues, while connecting to artists around the world.

We seek to bring a sense or caring and humanity. The Artnauts stand for the intersection of critical consciousness and contemporary artistic practice.”

Faris Amazonia Consumers :Giant Amazonian Leech Grows up to 18″ and lives for 20 years off the blood of other creatures

Suzanne Faris Amazonia (detail)

One of the most fascinating locations that the Artnauts have travelled to is the Amazon river, where they collaborated with local tribes and communities. I am still trying to sort out the information about this and will revise my discussion when I learn more. Suzanne Faris’s amazing sculptural installation speaks to greed, consumerism and the gobbling of resources.

Beth Krensky Bethlehem Palestine Birth(Place) Home(land

Beth Krensky has created a long white truce flag shared between the Israelis and Palestinians. Made of white handkerchiefs baby t shirts, etc each olive pole that it hangs from is inscribed with a quote from a mother who has lost a child

Jerusalem mother:

“For me the struggle is not between Palestinians and Israelis,nor between Jews and Arabes. The fight is between those who seek peace and those who seek war. My people are those who seek peace”

Nablus mother:

I’ve known Israeli bereaved mothers for many years. The mothers’pain is similar, no matter if they are Israelis or Palestinians . . . the pain is seared into us and will be with us forever.”

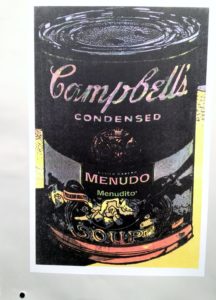

Tony Ortega Mexico: Amenudo crossing -memory remains

Ortega detail warhol crossed with Menudo soup on logo

And on the theme of the Mexican border crossing Tony Ortega’s work included the theme of hybridity, crossing a “Warhol soup can” with a Mexican soup in an installation that included a hybrid flag and a water barrel providing water for border crossers.

Kim V Martinez Mexico and United States 7 steps forward 7 steps back

Kim V Martinez also spoke of the border crossing, its difficulties and its dangers, referring to those who died within one small area.

These are only a few of the artists represented by the collective and in the special exhibition. George Rivera has carefully published a catalog of each exhibition and deposited the archives with the Lilas Benson Latin American Collections at the University of Texas at Austin, so their legacy for future historians is assured. Amazingly enough, they have not received any reviews in the past 20 years in the United States!

The Artnauts are deeply committed to speaking through their art of injustice. They speak in many voices, directly, poetically, politically, metaphorically. They speak of peace, of land, of consumption, of greed, of death, of hope, of perseverance. It was truly inspiring to meet them in t he week of our disastrous election.

We can look to these artists and others as we plan our resistance to the national nightmare currently unfolding like a slow, long-lasting earthquake.

This entry was posted on December 3, 2016 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Uncategorized.

“Liberty Denied: Immigration, Detention, Deportation” an exhibition

This exhibition co curated by myself and Mark Auslander, Asociate Professor of Anthropology and Museum Studies is at the Museum of Culture and Environment, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, Wa until December 10, 2016

Wed to Fri 11-4 and Sat 10-3

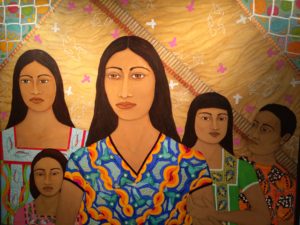

Cecilia Concepción Álvarez

Con Las Esperanzas de Vida

acrylic on canvas 2016

“In this piece I attempt to spotlight the horrific conditions that refugees from violence suffer in detention centers. We the American taxpayers subsidize these for profit detention centers with our taxes. These detention centers predominantly incarcerate refugees from Mexico and Central America. These people are held indefinitely in deplorable, dehumanizing conditions and subjected to the same type of violence they were fleeing from in their home countries. These peoples’ migration has been spurred by the violence created by USA drug addiction, arms sales and USA policies/CIA/Corporate destabilization of their governments.

In order to heal the wounds of capitalistic colonialism, we need to be honest and interested in creating a discourse and action plan that confronts the violence. We need to examine our part in creating this sorry state of affairs.

In my artwork I attempt to bring to light the parts of our society that are rendered invisible/without value; in a visual vernacular that does not use violence as a symbol of power/excellence. Each person held without legal recourse has a story and a reason to flee. They come here with the hope of life.”

Art Hazelwood Drug War Free Trade

Immigrants arrive in the United States with hopes of a better life. Coming from Guatemala, Nicaragua, Mexico, they are driven to leave their homes by the forces of free trade that bankrupt small farmers, climate change which devastates crops, by gang warfare, and drug mafias, some of which are referenced in Art Hazelwood’s incredible print. Note especially that the field, the ground is filled with skulls!

Those who do not cooperate with gangs and drug dealing are personally in grave danger even in their own homes. As a result, brave migrants cross harsh deserts for thousands of miles by train, truck, car and foot to cross into the United States in hopes of a safer life in which they can earn a living and support the family they have left behind.

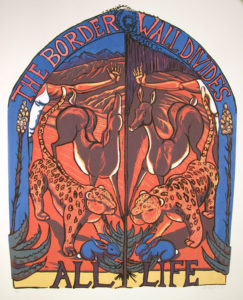

The Border Wall Divides All Life

Art Hazelwood Security

The border is today a militarized zone that divides not only families, but also animals and all life, as seen here in Art Hazelwood’s prints

Since numerous obstacles make legal migration possible only for the most privileged, migrants must pay thousands of dollars to coyotes to help them cross the border without papers. Once here, they often miss deadlines for applications because of constant moves, making documentation impossible once again.

Our farms require the hard work of migrant laborers, too hard for most of us. Capitalism invites them in, and then beats them down.As a result of their undocumented status, immigrant workers are frequently forced to live in unsafe conditions, suffer abuse on the job, or shortchanged on their pay.

Deborah Faye Lawrence Welcome to the NW Detention Center

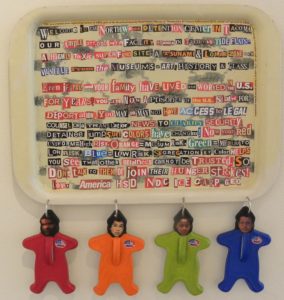

The collaged text on Lawrence’s work reads

“Welcome to the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma. Our ample 277,000 sq.ft. facility stands in Tacoma’s Tide Flats- a highly toxic superfund site; A Tsunami and Lohar zone that’s visible from the museums of art, history and glass. Even if you and your family have lived and worked in the US for years, you are now a prisoner of the U.S. slated for deportation. You may or may not have access to legal counsel or a translator or news! To clarify security, detainee jumpsuit colors have changed! Now your Red uniform= high risk. Orange=medium risk. Green=medium to low risk. Blue=low risk. Segregation by color helps you see that other detainees cannot be trusted. So don’t talk to them or join their hunger strikes!”

When Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) identify undocumented immigrants, often as a result of a minor traffic violation or racial profiling, they put them in detention. Over 30,000 immigrants are detained in 200 detention centers nationwide. With over 1500 beds, the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, run by the for-profit GEO Corporation under a contract with ICE, is one of the largest in the country. The detainees live in inhumane and illegal conditions with no privacy, poor health care, no outdoor exercise and terrible food. They are forced to do the work of the center for 1$ a day no matter how many hours they work.

Since lack of documentation is a civil offense, detainees have none of the rights provided by our criminal justice system. Their only option is to attain “relief” through pro bono lawyers such as those at the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project. A judge decides the case, without a jury. Many of the cases drag on for months and years. Deportees are taken to buses often in the middle of the night and returned to countries in which they have often never lived or left many years ago, leaving behind families in the US.

The artists in “Liberty Denied” explore some of these experiences. Blanca Santander speaks of the jolting cultural adjustments of immigration, but celebrates the strength of women who survive it.

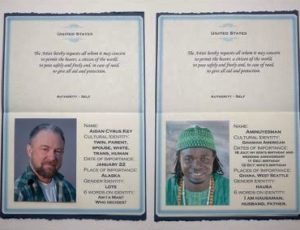

Carino del Rosario reveals the ironies and absurdities of passports as a means of identification.

Cecilia Alvarez represents the suffering of families separated by detention and deportation. (see her statement at top of post)

Tatiana Garmendia, originally from Cuba, describes her own family’s experience of torture in detention, sewn painfully into a blanket. That is the artist with me next to the chair.

Doug Minkler pointedly depicts the cruel contradiction of our current attitude to immigrants.

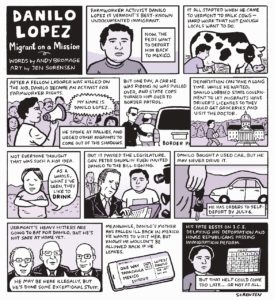

Jen Sorensen tells the story of immigrant activist Danilo Lopez and

Daniel P. Mendez-Moore outlines the hypocrisy of public policy.

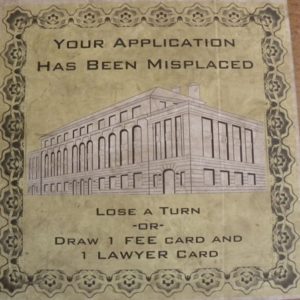

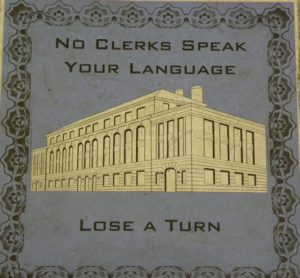

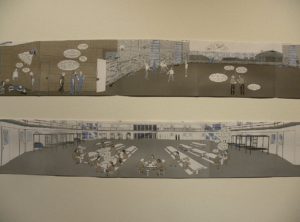

Three works were originally commissioned by the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian-Pacific American Experience in Seattle as the old Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) building in Seattle

(which held 230 people and also serviced people who wanted to become naturalized) was vacated for the new facility in Tacoma

(which holds over 1500 people in even worse conditions with only housing provided, no windows, no privacy).

Dean Wong’s haunting photographs document the empty, eerie building. Robb Kunz provides brief segments from interviews with immigrants about their experiences.

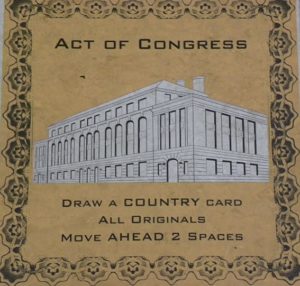

Christian French gives us the “INS Game,” the arbitrary process of acquiring legal status, still embedded in the floor of the INS building, here adapted as a card game.

Manuel Rios speaks of Identity Theft in his disturbing painting of a blindfolded person against barbed wire, suggesting both the act of immigration and the fearful aftermath.

Eroyn Franklin, in a fold out book format, follows the lives of two detainees in detail, Many Uch, in the old INS building, and Gabriella Cubillos (Gabi) in the Northwest Detention Center, both during their detention and after their release.

Last, detainees themselves make art to pass the endless time in a detention center with no programming, no courses to take, no recreation, nothing to do, except being forced to work as virtual slave labor for $1. per day no matter how many hours they work. These amazing purses come from Pavel Bahmatov. They are made of wrappers of ramen cut with dental floss, painstakingly woven together.

Pavel Bahmatov

The exhibition opening included a former detainee speaking forcefully of the dreadful conditions at the Northwest Detention Center, as well as students who are currently protected by DACA, delayed action for childhood arrivals, who spoke through surrogates to protect their identity.

The purpose of the exhibition is to shed light on the nightmares of immigration, as well as the positive contribution that immigrants make to this country. It also makes reference to the larger political and economic realities.

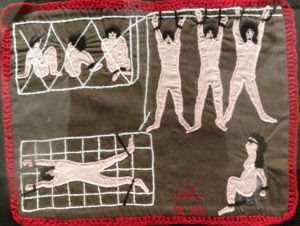

“Liberty Denied” is paired at the Museum of Culture and Environment with a stunning exhibition of Arpilleras, “Tapestries of Hope,” created by the mothers of the disappeared in many cases from the clothing of the disappeared. This private collection of works belonging to Marjorie Argosin includes detailed and poignant imagery. The experiences of the families of the disappeared make haunting parallels to the nightmares that today’s immigrants and their families experience during Immigration Raids, then arbitrary detentions and deportations In Chile though there have been tribunals and even monuments to the crimes of those years. Perhaps someday the US will recognize that it is committing the same crimes.

The children left behind

Scenes of Torture

Taken Away

No to Impunity

This entry was posted on October 11, 2016 and is filed under Uncategorized.

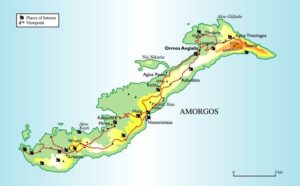

Constellations (Asterismos) on Amorgos in the Cyclades

Constellations, the creative artistic festival on the island of Amorgos, is in its fourth year, organized by a group of 10 volunteers who live on Amorgos, two of them originally from the island. Amorgos is part of the Cyclades group of islands, its more famous islands are Mykenos, Santorini, Naxos, Paros and Syros.). It is less well known partly because it has no airport. You have to take a ferry there (8 hours from Athens, 3 hours from Naxos).

The festival celebrates the island and its amazing out of the way villages, churches, and landscapes. The island is rugged, formed of hard metamorphic and volcanic rock. It used to have forests and a lot more terraced hillsides. Today it has goats, donkeys, mules, olive trees, wild herbs (we always come back with oregano and sage,) and religious festivals. There are some beaches, great hiking, and good food. You can do yoga at Iris Studio by the beach, you can get acupuncutre and herbal tea from Vangelis in Langada, you can get a fantastic manicure from Elpida in Aigalis. But above all it is a beautiful friendly island with many amazing landscapes, houses, rustic churches and stunning villages without any cars. There is one road for cars from one end of the island to the other.

According to the organizers, the idea of the festival is to celebrate

“A diverse, beautiful place bursting with history and emotion.A circle of friends loving, and living on an Aegean island.This is Amorgos, and this is us. For the past three years talented artists from all over Greece have showcased their creative work, honoring us and our guests with their presence, and bringing life to the island. Our goal for the 4th year of the festival is to encourage more artists to participate.

All performances take place next to ancient monuments, surrounded by landscapes of rare natural beauty without any complex stage settings.

No one involved in the organization of Asterismos (the Constellation), or any artists, is profiting financially in any way. Everything in this festival is created and offered out of love for the arts and the island.”

From Wednesday June 15 to Sunday July 3 they had events all over the island.

We saw three events while we were there.

SaGyni Dance Theater by Fizz dance group took place in the last rays of the sun on a path to the famous Church of the Panagia Epanocholini. The path was just wide enough to provide a space for performing. The group began with a dance that for me evoked a connection to the most archaic kore and goddesses.

Amorgos is famous for the largest Cycladic figure ever found, which is now in the Archeological Museum in Athens. As these woman danced in their nude stocking costumes they appeared to be part of the earth, joined to a mythic past. They were like the Kore of the archaic era coming to life.

The stripping of that outer garment was clearly an act of liberation. The three dancers continued with several different dances and poetic recitals that evoked contemporary lives for women and feminist issues:

a scene of seduction between two women, a competition among the three women performed on chairs, signified by exchange of clothing, such as a jacket, a shirt and hat signifiying a man, reaching out and rejection, playing cards, high heel shoes, all of these performances and exchanges suggested emotional relationships. The three women are struggling to find a way. They were sometimes accompanied by recitations, but that was in Greek so I couldn’t understand the words, but the implication was musings and philosophical responses on the theme of women. The connection of the landscape and the dance/theater was perfect, they blended gently with the setting of the ancient stone walls, reddish bushes, and soft pink flowers, the setting sun, the cooling wind.

Then up the path came a man with his donkey! In Amorgos, donkeys are still very much the only transportation away from the single road. They are working donkeys that help to carry many things.

The Greek farmer leading the donkey could not pass, as we were seated on steps and blocked the road. He stayed and watched, although the donkey showed no interest and went to sleep.

It was a thrilling partnership to the avant-garde artistic performance, two worlds, two lives, respecting each other, and part of the spirit of the Constellations festival on the island.

The next night we went to a performance for children called “Concerto for Double Bass and Wolves”

Dramatized narration by Mary Terzaki with Dimitris Sandalis on the bass cello.

It was a retelling of fairy tales with wolves, recasting the wolf as a hero instead of as a scary character. At the end all of the children got up and danced along with Mary as they exchanged masks.

The last Constellation event that we went to was the theater performance “It’s been a year” by the Eos theater group from Athens.

It was performed by seven actors at twilight on the top of a hill crowned by the famous Panagyia church of Amorgos. We see the playwright, Natalia Stulianou , below in the foreground, with her back to us.

We see the playwright, Natalia Stulianou , below in the foreground, with her back to us.

The acting was so good that I could sense what was happening even without understanding what they were saying. The story is told through the eyes of a young man, exploring his family home and thinking about his ancestors. You see him in the background in the blue shirt

The Eos dance group is special. It emphasizes engagement with the audience. As they describe themselves “ EOS was founded in 2012 with the vision for an accessible expression and research in all forms of art, culture and social affairs. . . EOS runs several theatre training programs for young people, including programs for the training of young immigrant children . . .”

The full names of the cast in the play that we saw and the era that they represented is here:

One: Thalis Politis (First war 1914 – 1918)

Two: Semina Panigyropoulou (Second war 1939 – 1945)

Three: Dimitra Drakopoulou (Smyrna 1922)

Four: Iakovos Midrinos (the Civil War 1946 –1949)

Five: Angeliki Srati (the Dictatorship 1967 – 1974) –Natalia Stulanou, the playwright, was playing that part in Amorgos

Six: Dimitris Kakavoulas (the Economic Crisis starting in 1980 as a Greek broker in New York, who commits suicide)

Seven: Christos Dyonisopoulos (who lives today, brother of Six, and tries to find out about the lives of his ancestors, which are all the above)

I was so fortunate to be visiting my sister in law, who lives on the island of Amorgos, during this amazing festival.

This entry was posted on July 31, 2016 and is filed under Amorgos Greece, Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Uncategorized.

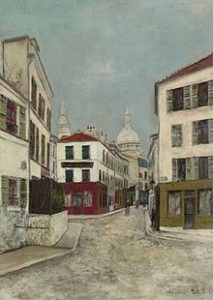

Montmartre!

Le Bateau Lavoir 2016. Burned down in 1970. The window tells its history

Montmartre! After teaching art history for over 30 years and reciting the tale of Picasso creating Cubism with Braque at the Bateau Lavoir, I had no idea really of exactly where it was or the great significance of Montmartre historically as a place of revolutionary ideas, as an independent enclave in Paris, and as a site of intersection for the avant- garde starting as early as the impressionists and lasting until World War I. All his life Picasso looked back on his years in Montmartre as the best of his life. His connection to the musicians, poets, singers, dancers, as well as its radical political history, profoundly shaped him. It was easier to break rules in Montmartre.

Its earliest story is the reason for its name, Mount of Martyrs, St Denis was martyred there, and of course the story is that after decapitation he picked up his head and walked away preaching all the way. He is the patron saint of Paris. ( That’s him on Notre Dame with his head).

And even before the artists arrived in the late 19th century, Montmartre has a thrilling history as one of the centers of the Paris Commune of 1871. Again I always knew about Courbet advocating and helping to pull down the column in the Place Vendome of Napoleon I, but he was also part of the Commune in Montmartre along with many other vivid personalities such as the Red Virgin, Louise Michel , an ardent revolutionary. Women played a major part in the commune as active warriors. After the fall of the commune Michel was exiled, but after the amnesty for the radicals in 1889 she came back to France and continued to be a radical and activist.

The commune was brief, from 18 March to 28 May 1871 but of monumental importance in the history of radicalism: During those few weeks, the communards abolished the death penalty, and military conscription, for starters, then rights of workers, free secular education, equal pay for men and women, separation of church and state, requisition of empty houses for homeless, citizen status for foreign inhabitants. All great ideas that we still need today! The communards inspired Marx and Engels as an example of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and it was an inspiration for the Russian Revolution.

Right after the commune, the Catholics began the huge Sacre Coeur, an obvious way of physically squashing the rebellious history of Montmartre with this gigantic building. It was completed in 1914, exactly the year that Picasso and the avant-garde left Montmartre. It was no longer the radical village they had come to, it was now an outpost of the city and its oppresions. Yet even today

Montmartre still feels like an isolated enclave with a different character than the rest of Paris. When we descended the butte to go the Grand Palais, I was overwhelmed with the heavy Second Empire architecture.

Henry serenaded by a second empire musician

Montmartre has miraculously retained its atmosphere (although now the homes are those of the wealthy), but the streets look like those of Utrillo’s paintings.

The steep streets prevent most cars from using them, the sand colored buildings, the paving stones, and of course “Le Moulin de La Galette,” the only surviving windmill from the 16th to the late 19th when there were 30 windmills that ground the wheat of the farms there.

“Le Moulin de la Galette”, so familiar to us from Renoir’s painting is a later name for a now decorative windmill, named for a homemade brown bread.

The restaurant has just reopened this spring, but of course it is an ultra chic place now, not the public garden seen in Renoir’s wonderful painting. The artists used to gather here for outdoor dancing every Sunday, but that large space is now gone.

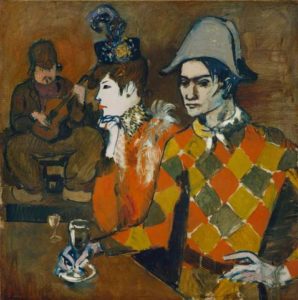

There were poets, musicians, writers, painters, sculptors, dancers, singers, all friends, all going to cabarets together. We went to Au Lapin Agile, still there, still the same atmosphere of intimacy with the singers, of all ages ever since 1860!. Wonderful dark interior and we were given a cherry liqueur as we listened to poetry, humour and revolutionary workers songs. The singers encouraged us to sing along as they walked among our tables.

The Lapin Agile still encourages young singers as well as supporting older singers. On the walls were an eclectic mix of different paintings, sculptures ( Buddha, Christ ). One of the singers spoke of Apollinaire and Picasso, among others, who enjoyed the music and poetry there. I could almost feel them still sitting there. One of Picasso’s paintings of patrons in the Lapin Agile used to hang there.

In the Place du Tertre, handsome painters offer to paint our portrait. Some of them were quite good!

The Musee de Montmartre including the garden where Renoir painted the Swing, displayed historical images of Montmartre, of the commune and the martrydom of St Denis, and a recent exhibition “Artistes a Montmartre from Steinlen to Satie 1870 – 1910” which emphasized the role of artists like the radical protestor of injustice, Steinlen, Toulouse Lautrec, and Degas who encouraged Suzanne Valadon to become an artist.

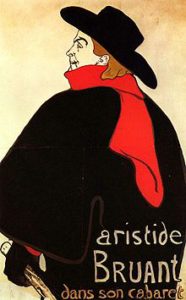

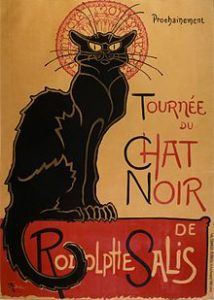

Perhaps most significant was Aristide Bruant, singer of the famous cabaret Chat Noir ( famous logo of cat with a Byzantine halo) who created the “chanson realiste” style that we heard “Au Lapin Agile.” The singers at Au Lapin Agile all wore black with red accents matching the Toulouse Lautrec painting of Bruant.

(and note the painter in the square also wore that color scheme)

Santiago Rusinol of Satie admiring Valadon on the piano