Montmartre!

Le Bateau Lavoir 2016. Burned down in 1970. The window tells its history

Montmartre! After teaching art history for over 30 years and reciting the tale of Picasso creating Cubism with Braque at the Bateau Lavoir, I had no idea really of exactly where it was or the great significance of Montmartre historically as a place of revolutionary ideas, as an independent enclave in Paris, and as a site of intersection for the avant- garde starting as early as the impressionists and lasting until World War I. All his life Picasso looked back on his years in Montmartre as the best of his life. His connection to the musicians, poets, singers, dancers, as well as its radical political history, profoundly shaped him. It was easier to break rules in Montmartre.

Its earliest story is the reason for its name, Mount of Martyrs, St Denis was martyred there, and of course the story is that after decapitation he picked up his head and walked away preaching all the way. He is the patron saint of Paris. ( That’s him on Notre Dame with his head).

And even before the artists arrived in the late 19th century, Montmartre has a thrilling history as one of the centers of the Paris Commune of 1871. Again I always knew about Courbet advocating and helping to pull down the column in the Place Vendome of Napoleon I, but he was also part of the Commune in Montmartre along with many other vivid personalities such as the Red Virgin, Louise Michel , an ardent revolutionary. Women played a major part in the commune as active warriors. After the fall of the commune Michel was exiled, but after the amnesty for the radicals in 1889 she came back to France and continued to be a radical and activist.

The commune was brief, from 18 March to 28 May 1871 but of monumental importance in the history of radicalism: During those few weeks, the communards abolished the death penalty, and military conscription, for starters, then rights of workers, free secular education, equal pay for men and women, separation of church and state, requisition of empty houses for homeless, citizen status for foreign inhabitants. All great ideas that we still need today! The communards inspired Marx and Engels as an example of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and it was an inspiration for the Russian Revolution.

Right after the commune, the Catholics began the huge Sacre Coeur, an obvious way of physically squashing the rebellious history of Montmartre with this gigantic building. It was completed in 1914, exactly the year that Picasso and the avant-garde left Montmartre. It was no longer the radical village they had come to, it was now an outpost of the city and its oppresions. Yet even today

Montmartre still feels like an isolated enclave with a different character than the rest of Paris. When we descended the butte to go the Grand Palais, I was overwhelmed with the heavy Second Empire architecture.

Henry serenaded by a second empire musician

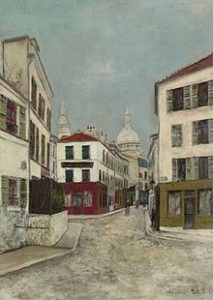

Montmartre has miraculously retained its atmosphere (although now the homes are those of the wealthy), but the streets look like those of Utrillo’s paintings.

The steep streets prevent most cars from using them, the sand colored buildings, the paving stones, and of course “Le Moulin de La Galette,” the only surviving windmill from the 16th to the late 19th when there were 30 windmills that ground the wheat of the farms there.

“Le Moulin de la Galette”, so familiar to us from Renoir’s painting is a later name for a now decorative windmill, named for a homemade brown bread.

The restaurant has just reopened this spring, but of course it is an ultra chic place now, not the public garden seen in Renoir’s wonderful painting. The artists used to gather here for outdoor dancing every Sunday, but that large space is now gone.

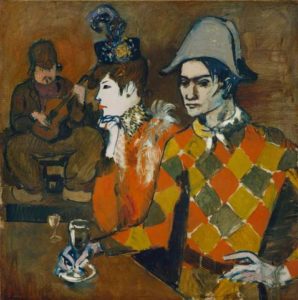

There were poets, musicians, writers, painters, sculptors, dancers, singers, all friends, all going to cabarets together. We went to Au Lapin Agile, still there, still the same atmosphere of intimacy with the singers, of all ages ever since 1860!. Wonderful dark interior and we were given a cherry liqueur as we listened to poetry, humour and revolutionary workers songs. The singers encouraged us to sing along as they walked among our tables.

The Lapin Agile still encourages young singers as well as supporting older singers. On the walls were an eclectic mix of different paintings, sculptures ( Buddha, Christ ). One of the singers spoke of Apollinaire and Picasso, among others, who enjoyed the music and poetry there. I could almost feel them still sitting there. One of Picasso’s paintings of patrons in the Lapin Agile used to hang there.

In the Place du Tertre, handsome painters offer to paint our portrait. Some of them were quite good!

The Musee de Montmartre including the garden where Renoir painted the Swing, displayed historical images of Montmartre, of the commune and the martrydom of St Denis, and a recent exhibition “Artistes a Montmartre from Steinlen to Satie 1870 – 1910” which emphasized the role of artists like the radical protestor of injustice, Steinlen, Toulouse Lautrec, and Degas who encouraged Suzanne Valadon to become an artist.

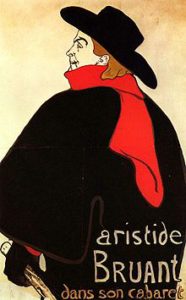

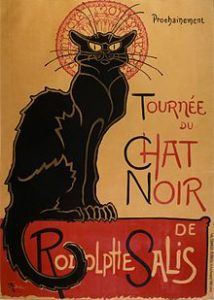

Perhaps most significant was Aristide Bruant, singer of the famous cabaret Chat Noir ( famous logo of cat with a Byzantine halo) who created the “chanson realiste” style that we heard “Au Lapin Agile.” The singers at Au Lapin Agile all wore black with red accents matching the Toulouse Lautrec painting of Bruant.

(and note the painter in the square also wore that color scheme)

Santiago Rusinol of Satie admiring Valadon on the piano

The highlight of the exhibition was the love affair of Eric Satie and Suzanne Valadon in 1892. Satie’s music was playing as we looked at some of his love letters to her, as well as her painting of him as a young man, before his suave identity as the ultimate Bohemian had formed. Satie wished to capture in music the instant seen in the impressionist painting, as well as connect to the real world.

Kupka, Bonnard, Bernard, Dufy and others who are less famous, but equally provocative all lived in Montmartre. Van Gogh was not in the exhibition, but he too lived in Montmartre. We saw a studio that belonged to Valadon and later artists, as well as Utrillo’s bedroom (Utrillo is Valadon’s son).

At the beginning of the 20th century, Picasso arrived in Montmartre and he began to publish images ala Toulouse Lautrec in a small newspaper there.

The famous Bateau Lavoir was home to many painters, musicians, and poets, and the scene or Picasso’s famous banquet for Douanier Le Rousseau, the artist who inspired the other artists with his “primitive” style.

We were fortunate that while we were in Paris there was a major exhibition of the Douanier Rousseau as well as Apollinaire. Rousseau’s well known paintings still thrill me with their direct color, design and subjects.

Apollinaire is the experimental poet, and art critic, who wrote some of the first analysis of Braque and identified the Cubists as a group. When he died of influenza in 1918, an era ended for the avant-garde in Paris.

Henry at a Montmartre Cafe

chess players (note that red and black theme again)

rainy afternoon in Montmartre

The scenic Cafe Poulenc

Mona Hatoum at the Tate Modern

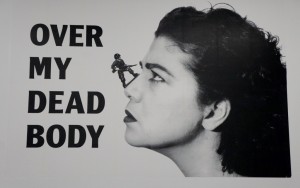

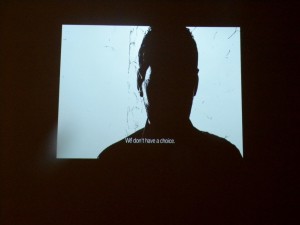

While this early poster/billboard by Mona Hatoum might seem amusing at first, it is actually deadly serious and not a pun.

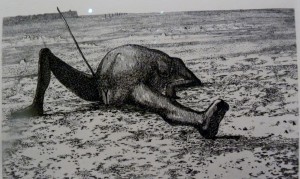

Mona Hatoum confronts us directly with the nightmare of violence in her early performance work. Here is a description of Variations on Discord and Divisions (1984) “. . . the artist, wearing an opaque mask and all dressed in black, crawls between the rows of spectators to reach the performance space. She then performs a number of actions that culminate with her removing raw kidneys from under her clothes, cutting them up, putting them on plates, and serving them one by one to the audience.” (“A Prologue to the Past and Present State of Things

Variation on Discord and Divisions: Mona Hatoum, Ibraaz,

009_00 / 2 July 2015)

Below is a still from that performance of the early 1980s. It could have been made yesterday. It captures the horror of unexplainable violence. We in the West like to say that only Islamist (ie politically motivated and brainwashed) terrorists commit the kind of barbaric acts suggested by this image, but of course it is all of us. (The recently approved US budget for combat operations alone was 40 billion). Anonymouos drone attackes and ongoing murders of black people by police in the US are only two examples.

Learning of the visceral intensity of Hatoum’s early work transformed my understanding of her art. It came through even in the documents of the 1980s performance pieces in the current exhibition at the Tate Modern. In them you see the artists’ highly compressed emotions of anger and frustration with the political situation in Palestine and the Middle East. As a Palestinian refugee in Beirut

(albeit a privileged one with a British passport), she felt deeply displaced when she was unable to return home from London on what was to have been a short trip because of the Civil War in Lebanon.

Live Work for the Black Room

Three works represented by photographs and notes are Live Work for the Black Room 1981, Under Siege, 1982 and The Negotiating Table 1983. In the first ( above) described by the artist as about “death, disaster, doom and gloom,” she falls to the floor repeatedly in a completely black room, drawing a chalk outline of her body, then places a candle next to it. The photograph has an odd abstract quality, although details show the outlined bodies clearly, as in a crime scene.

Under Siege

In Under Siege she stands inside a transparent cube covered in clay, then falls down repeatedly for seven hours.

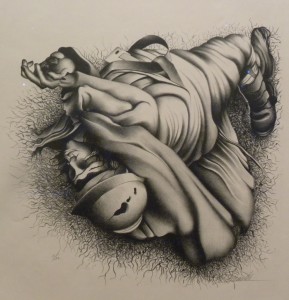

The Negotiating Table

Repetitive falling changes to stasis in The Negotiating Table: the artist encased and immobilized by bloody entrails, her head covered in gauze, lies motionless on a table assuming the aura of a sacrificial animal. Empty chairs surround her: failed talks lead to dead people. All of these works have soundtracks of war news and leaders talking about peace.

In these same years, Hatoum also explored video art, but in an entirely different way from feminist video in the US. She immediately perceived the camera as a physically invasive force. During Don’t Smile You ‘re on Camera, 1980 she moves a camcorder across the bodies of individuals in a small audience, alternating those images with projections of naked bodies.

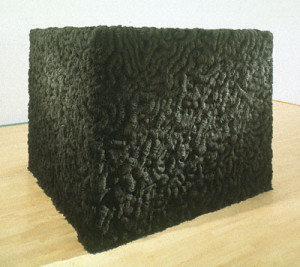

She continues this exploration of the body in literal depictions such as Socle du Monde 1992-3, a large cube with “intestines” covering its surface, evoked through iron shavings that curl convincingly as the tubes of our innards.

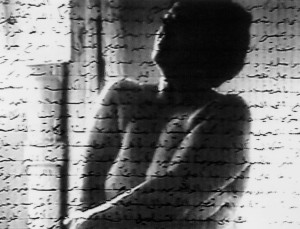

Measures of Distance, 1988, records her mother in the shower (shown behind a “curtain” of Arabic script that resembles barb wire). The artist reads letters from her mother as the text of the piece that address both her mother’s own deep sadness in exile, and her relationship with her daughter. One of Hatoum’s best known works, Corps Etranger 1994 takes the idea of photographic penetration much further by filming medical imaging footage penetrating her own body. We stand on top of the video as another invasive force as we watch it probe her inner body.

But in spite of her intense performances and intimate explorations,

only once in her entire career, in Measures of Distance, does Hatoum include personal details. Otherwise we only have the fixed, brief biography of her early years in Beirut and move to London. We know nothing else of her life.

Hatoum’s concern is to make the feelings of her art penetrate us. She does not want us to have an opportunity to tell a story, to narrate a context. She manages to convey the large atrocity of war, destruction, and exile, without any specifics at all. In that way, she rises above who she is, and who we are, and speaks of the human condition as we reap the emotional harvest of violence.

Undercurrent exemplifies her understated metaphors open to several interpretations: at the same time that it terminates its spiraling paths of red electric cord with light bulbs that suggest an ending, and a woven center that may suggest collective resistance, it can also be alluding to bleeding to death, electrocution and torture. Even as the poetry of the piece captures us, we are enmeshed in its multiple meanings.

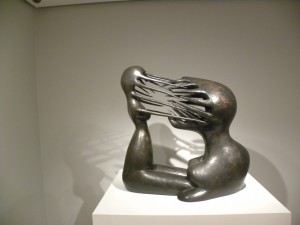

That subtle ambiguity is obvious in Hatoum’s ongoing use of her own hair as a major material for her art, in entire installations of balls of her hair, or sewing with hair and most remarkably, weaving the particular pattern of the Keffieh with hair (which some writers explore from a feminist perspective). Those cast off dead cells, that fragile filament, becomes a layered statement about death, life, and their eerie balance. The delicacy of the works made of hair make them recede almost into invisibility, but that invisibility is the point.

In contrast to invisibility, another experience in Hatoum’s work is a sense of threat, entrapment, and anxiety. Through a barbed wire fence we view Home 1999, a table covered with ordinary kitchen appliances like colanders and cheese graters that serendipitously lights up and creates loud noises. The unpredictable threat to what should be the security of home is a theme the artist explored as early as 1979, and it has many iterations such as Homebound, 2000, shown at “Documenta” in 2002 which included a bed, crib, and chairs.

Sometimes we have just a huge grater as a room divider or a bed. These works have been compared to Martha Rosler’s famous Semiotics of the Kitchen of 1975. Rosler also transforms ordinary kitchen implements into threatening objects. But for Rosler, she holds the knife, she wields the threat, and for Hatoum the threat comes randomly from outside, beyond her control. Hatoum references the impact of war on individuals, while Rosler redefines and defies social expectations for women, a very different point of reference.

Sometimes we have just a huge grater as a room divider or a bed. These works have been compared to Martha Rosler’s famous Semiotics of the Kitchen of 1975. Rosler also transforms ordinary kitchen implements into threatening objects. But for Rosler, she holds the knife, she wields the threat, and for Hatoum the threat comes randomly from outside, beyond her control. Hatoum references the impact of war on individuals, while Rosler redefines and defies social expectations for women, a very different point of reference.

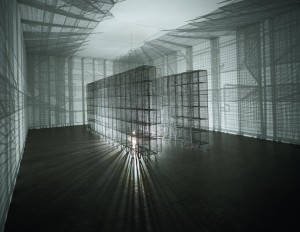

Deeply affecting in its simplicity, Light Sentence 1992, features a room with stacks of small cages arranged in two rows, some with their doors open, lighted by a single bulb that rises and falls between the rows. The magic of the piece and its contradiction is the shadows of the cages cast on the walls, constantly moving, mesmerizing abstract patterns. The shadows escape the entrapment of the cages. Poetry competes with claustrophobia.

Hot Spot, 2006, a grid/globe with red neon marking the continents joins her ongoing manipulations of maps, globes, and borders as in Map made from glass marbles on the floor, escaping their geography,

or the map of the world created by removal of fibers in a woven carpet, Bukhara (red and white).

As the marbles slip around the floor and the carpet conveys the absence or the globe’s glow spreads through a room, the concept of mapping and borders as an arbitrary source of conflict and war is obvious. And of course it all comes back to Israel /Palestine, the root of Hatoum’s own exile and that dreadful unsolvable conflict based on the colonial decisions of over one hundred years ago.

Present Tense, 2200 blocks of Palestinian olive oil soap and red beads marking the Oslo Peace Accord of 1993

The early performances provide the foundation for all that follows in Hatoum’s work.

While the artist’s body now appears only in its dead cells (hair, nails, blood), Hatoum expresses the same violence and compressed terror through the ordinary objects of everyday life and in our own lives. Hanging Garden as installed at the Tate, brings it home: bunkers that have stayed so long that they have grown grass. By looking at the metaphors latent in the objects she chooses from our daily life, we feel inside us the corruption of humanity in our intensely violent world.

Mona Hatoum looking through the barbed wire of her installation Impenetrable

This entry was posted on July 12, 2016 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in Beirut, Art in War, Contemporary Art, Feminism, Palestine, Uncategorized, Women Artists.

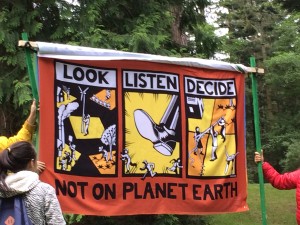

Break Free From Fossil Fuels Pacific Northwest Anacortes

The amazing weekend of protests in Anacortes featured many different actions, trainings, planning, spreadsheets, signs, artists, legal advisors, health professionals, food experts, miracles.

Only a few weeks of preparation produced incredible results. I want to salute everyone who took part in whatever aspect, all of us had a part to play large and small, active and supportive. It was a thrilling adventure and I am fully motivated to support the way forward in every aspect of my life.

At Deception Pass State Park, the center of planning and information, where I spent a lot of time, we had the beauty of the park to inspire us to make sure it has a future. I kept thinking about our ongoing drought and overheated planet, and wondering if the green Northwest can have a future.

In the kitchen there was breakfast for the many many campers, a massive vat of oatmeal, my very own homemade yogurt , tea, coffee

we made our lunches and were given dinners, a monumental planning job before hand. Hats off to all those who pulled it off!!

There was legal training for those who wanted to participate in civil disobedience. It was so helpful, what to say, how to act, we even role played, that I was tempted to think about it for the future, although going to jail is not my temperament. All was carefully planned and coordinated. I spent time helping with the info both that you see above.

Some people biked all the way from Seattle!

A lot of people were making art there

The absolute highlight for me was the Saturday Indigenous Day of Action,

“Its in Our Hands” was the theme.

We marched on the road next to the dreadful refineries, we chanted, sang, danced, with the indigenous peoples from many tribes.I put a movie on my facebook, I am not sure how to add it here.

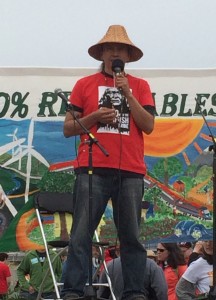

The rally after the march honored many people, but above all Mother Earth. I found it incredibly moving to hear elder Diane Vendiola of the Swinomish speak of growing up on the polluted point where we stood, eating fish and clams now no longer available, in water that is completely toxic.

The plants were built on unceded land taken away from the Swinomish by Ulysses Grant after the Civil War.

We had to breath the fumes from the Tesoro emissions, as we listened. We had to smell their acrid smell, it made the ceremonies all the more urgent and beautiful.

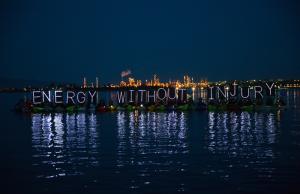

At 2 PM we had a water blessing ceremony led by Inez Bell of the Tulalip, in conjunction with ceremonies around the world. In addition to ceremonies, there were of course global Break Free actions to protest fuel plants and other massive sources of pollution, coordinated by 350.org and inspired by Bill McKibben.

Not long after we blessed the water, a canoe of Lummi youth arrived and the canoe came right into the center of our events, as a symbol of working together as a community. The Lummi sang an eagle song, and two young men danced an eagle dance as eagles circled overhead. I was too mesmerized to take a picture of the eagle dance.

Members of the Swinomish, our hosts, as well as Chief Ruben George, a leader from First People of Canada, youth and their leader Patsy Bane from the Makah, Tyson Johnson leader of the Quinault, and leader Jules James Lummi spoke of saving the earth, of honoring our ancestors, of the war we are fighting to survive, of the importance of giving up oil, fossil fuels entirely. James spoke of the horrendous fire in the Boreal Forest in the Alberta tar sands.

The Lummi were honored with a paddle by the Swinomish because they have just defeated a coal terminal. Jules James eloquently spoke of coalition building, working together. He has traveled to other tribes the Sioux, the Northern Cheyenne, for example, who are also saying no to toxic polluters.

Paul Che Oke’ Ten Wagner, the brilliant musician, spoke and posted his remarks on facebook. His shirt asks us to honor the Duwamish.

“It was an honor to speak at In Our Hands rally to help end the era of fossil fuel catastrophe, my point was that we must step back into the circle of life and learn to honor the gifts our Mother Earth has to offer us, the linear action of the colonial world has a finite end and if our Mother Earth reaches the tipping point, the point of no return for stable climate the human race will reach that end and there will be a great reciprocity or giving back to our Mother Earth but not of our liking…. It will be the bones of our grandchildren and their children being given back to our Mother Earth due to our lack of respect for the gifts our Mother” Paul Che Oke’ Ten Wagner

Because of the shifts I signed up for, I missed all the luminary events on water and on land. I have a few images from the water, and I am hoping the salmon march will post some photographs.

All of the news coverage addressed the arrests from the railroad sit in that blocked trains for three days. Probably because they were so well trained in civil disobedience, the people arrested were actually let go almost immediately.

Interesting that the arrests are given so much more space than the peaceful coming together and commitment of more than a thousand people.

I love this earth, I want it to survive for my grandchildren. Thank you Kayactivists, Indigenous, climate activists, so many people of all ages and stages of life who came together last weekend!

The youth of Plant for the Planet are my grand finale.

This entry was posted on May 18, 2016 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, Backbone Campaign, Contemporary Art, ecology, global justice, indians, Indigenous activism, Uncategorized.

“Mood Indigo: Textiles from Around the World”

“Dreamy blues/Mood indigo.”

—Duke Ellington, 1931

Breathe deeply as you enter the first gallery of “Mood Indigo, Textiles from Around the World,” then look carefully at the dried plants hanging on the walls. Now, enter a high enclosure of fabric dyed in many shades of blue and experience a constantly changing sound scape that evokes the sounds of color, and the color of sound. The collaborative contemporary installation Mobile Section, 2015, by textile artist Rowland Ricketts and sound artist Norbert Herber provides a perfect introduction to this highly original exhibition. It gives us the material qualities of the immaterial, color, created only by the refraction of light.

The first exhibition of textiles at the Seattle Art Museum since 1980, “Mood Indigo” features almost 100 different textiles and garments, many of them never before exhibited. While Pamela McClusky, Seattle Art Museum’s wonderful curator of Art of Africa and Oceania took the lead in the theme of the exhibition, she collaborated with the curators of Native American Art, Chinese Art, and Japanese Art, as well as, importantly, Nicholas Dorman, Conservator, and Paul Martinez, Installer, who solved the incredible challenges of installing flat textiles in a dynamic way.

Together they excavated the collections with an eye for indigo blue, a radical project.

Indigo does not actually exist in the world. It must be produced from a molecule in one of about 20 plants (of which there are 600 varieties). Rowland Ricketts explained the process in detail. When the plants reach waist high, they are harvested, dried, stomped on, mixed with water, left 100 days in compost, turned, sliced, watered, and bagged. The resulting paste ferments in a vat with wood ash, lime, and wheat bran (everyone around the world has a different formula, often a family secret). During the oxidation/reduction process as it is stirred daily, the color appears, like magic. Vats themselves apparently have attributes and respond to the person stirring it. The color comes alive in different ways according your own mood!

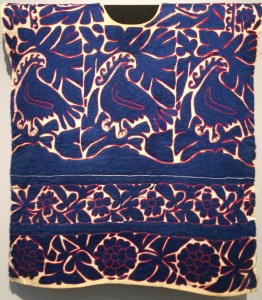

Guatemalan textile

Focusing on indigo textiles erases borders of geography and categories. Textiles here emerge from the margins established by European academic traditions that privileged painting and sculpture, and from the depths of storage at the Seattle Art Museum.

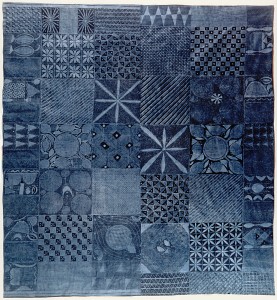

Adire Alabere Nigerian

The indigo textiles in this exhibition encompass all classes of society and all parts of our life. They cover us when we sleep and work, they ornament us for special events, they define rituals and ceremonies, they wrap us when we die. Indigo blue clothing signifies status and royalty, but it also covers the backs of peasants, prisoners (in the 1940s), and “blue collar” workers. The textiles contain secrets and symbols. The indigo blue suggests many emotions, sad, reflexive, humble or joyful.

The exhibition ranges from ancient African fragments to a towering Basinjom (spirit) mask and gown, from an imperial Chinese robe to a Japanese fireman’s outfit. It includes a Guatemalan cape, a Peruvian feather quilt, a contemporary American textile created from denim jeans,

Anissa Mack Broken Star

a Tlingit basket, a Javanese head shawl, a Laotian shawl and a Korean Bojagis.

Japanese kimonos fill an entire gallery like fluttering butterflies.

Colonial powers traded indigo in massive amounts, particularly from Bengal. Three huge Belgian tapestries made during the height of this trade anchor one gallery, each representing a different continent, Asia, America, and Africa. The allegorical royal figures seated at the center of the tapestries are dressed in blue fabrics, and they are surrounded by a wealth of symbols. Meticulously restored, the tapestries have never before been displayed by the Museum (they were a 1962 gift from the Hearst Foundation). Fascinating as they are to view, I felt that they recapitulated the oppressions of colonialism as they towered over clusters of tapestries from each continent. The egalitarianism of the exhibition was disrupted by their scale and their academic imagery, the three royal figures were all women draped in fabric that exposed their breasts.

The Belgian tapestries magnify the global scope of the exhibition, but the real joy of “Mood Indigo” is the range of cultures that it encompasses, and the many different directions that focusing on Indigo blue can take us. Curator Pamela McClusky even pointed out that in May we will have a blue moon (when there are two moons in one month).

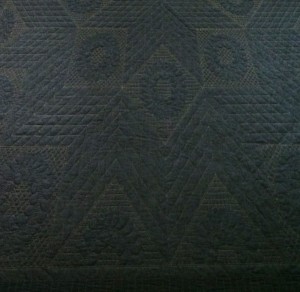

Annie Mae Young Gee’s Bend Quilt Blocks 2003

“The deeper blue becomes the more urgently it summons man toward the infinite, the more it arouses in him a longing for purity, and, ultimately, for the supersensual.”

—Wassily Kandinsky

at the Seattle Asian Art Museum

April 9 – October 9, 2016

Ajanta Cave I detail

reclining Buddha Ajanta Caves India

“Journey to Dunhuang: Buddhist Art of the Silk Road Caves,” March 5 – June 12, 2016

While you are at the Asian Art Museum, visit the exhibition of photography and painting based on the Buddhist art in the thousands of caves of Dunhuang, a World Heritage site in Western China. Now in a desolate desert landscape, it formerly lay at the crossroads of several civilizations on the “Silk Road”. The exhibition intersperses historical photographs from the 1940s by James and Lucy Lo, and replicas that they commissioned in the 1950s of some of the ancient paintings. It provides an insight into an important phase of Buddhist art that lasted from the fourth century to the fourteenth century. Some of these painters may have travelled from Ajanta in India, where you see similar caves with early carvings of giant Buddhas and stories of the life of Buddha painted on walls and ceilings.

This entry was posted on May 5, 2016 and is filed under Textiles, Uncategorized.

May Day Art and Writing Booth 2016

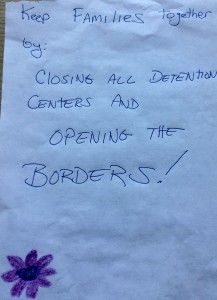

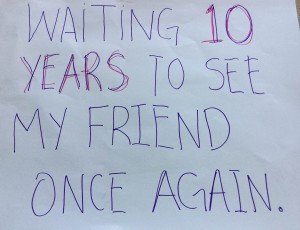

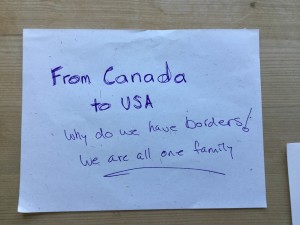

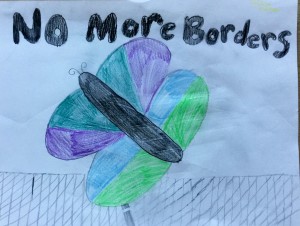

Yesterday Raul Sanchez and I had a booth at the rally before the Immigration March to support workers and immigrants rights.

We invited people to tell a short anecdote or draw a picture about how immigration laws had affected them.

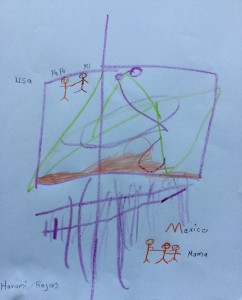

We had quite a few drawings and a few writings which I am posting here. The first drawing here by a young girl shows herself and her father separated by the wall from their mother in Mexico.

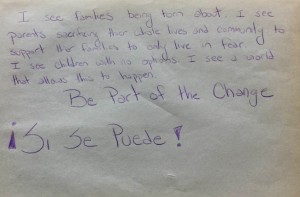

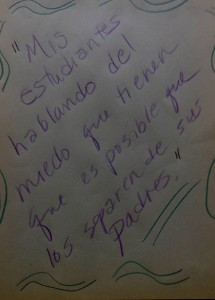

Translation: above left My students are afraid that it is possible they will be separated from the parents.

Above right ” I see families being torn apart. I see parents sacrificng their whole lives and community to support thier families to nly live in fear. I see children wtih no options. I see a world that allows this to happen! Be part of the Change Yes We Can Do It. !

This entry was posted on May 2, 2016 and is filed under Immigration, Uncategorized.

“Ai Wei Wei Fault Line” at the San Juan Islands Museum of Art

What a surprise to discover a beautiful new venue for contemporary art in Friday Harbor on San Juan Island. The San Juan Islands Museum of Art has existed in temporary venues for several years, but it moved into its current re purposed building a year ago, and hired a dynamic young director, Ian Boyden, 8 months ago.

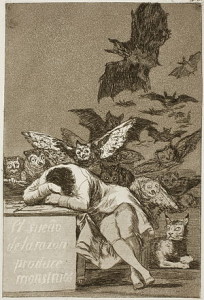

Not only is this a wonderfully intimate museum space, but Boyden just created a provocative three part installation that included Ai Wei Wei, and Goya both addressing the devastating cruelty of bureaucracy, governments, and soldiers. The third part of the installation by Dana Lynn Louis suggests moving the dark feelings from the other two exhibitions out into air and space.

Ai Wei Wei’s installation “Fault Line” is what brought me to Friday Harbor.

Following his dazzling and moving installation on Alcatraz Island last year calling attention to the identity of dozens of political prisoners detained all over the world, Ai Wei Wei has continued to have exhibitions which he has organized from China while he was under house arrest and unable to travel outside the country from 2011 to July 2015.

His strategies for making the invisible visible continues in this exhibition on a theme that he has addressed frequently: the death of over 5000 children in the Wenchuan earthquake of 2008.

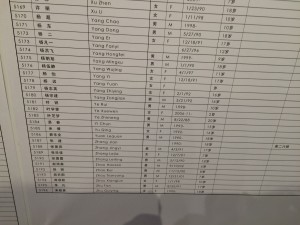

In this presentation, the list of names fills two walls of the museum, here you see the director in front of the list and, below, a detail of the last part of the list which ends with no 5196, Zhu Guiying a girl born in 1990. Each year on the child’s birthdays Ai Wei Wei posts on his twitter feed to honor that child.

Behind a partition, the video “Little Girl’s Cheek” 2008 interviewed the parents of the children who died in the collapsed schools. Ai Wei Wei hired researchers to gather the information.The parents, relatives and friends tried digging out the rubble covering the still living children with their bare hands when no help arrived. It is unimaginably painful to hear them describe the cries of the children.

The soldiers stood by doing nothing. When the parents protested they were barred from the site. When they went to officials they did nothing, explained nothing. The government harrassed the investigators that Ai WeiWei had hired. The parents were mostly peasants who had sacrificed everything for their children’s education and now had only a tragedy.

The officials blamed the earthquake for the collapse of the dozens of schools, but the shabby construction was clearly to blame.

In other installations by Ai Wei Wei on the subject of the children lost in the earthquake we have seen hundreds of backpacks, or piles of the rebar that collapsed. Ai Wei Wei bought tons of it and straightened it.

Here, we have shapes evoking coffins.

There are 8 coffin like forms made of rosewood, that seem like enlarged jewelry cases with black foam holding pieces of rebar carved in marble that seem to rise up from their containers like ghosts coming back to haunt us. “Rebar and Case” (2014) has not been shown in a museum before.

The juxtaposition of these three ways of representing the disaster overwhelmed me with the tragedy in a way that I had not been affected by previous installations. Part of the reason was the intimacy of the space in this small museum, where we walked between the coffin forms and looked down on the ghost rebars, thinking of the children buried still under rubble, most of them never properly recovered and given a funeral. Here was a graveyard of lost children, with unmarked graves.

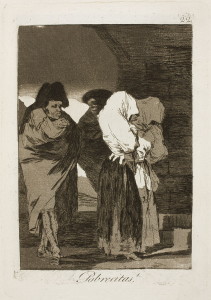

In partnership with this installation was the gallery of Goya prints with the title print on a poster “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.”

What could be a more appropriate partner to “Fault Line” than Goya’s Caprichos, that sarcastic representation of the inhumanity of the bourgeoisie aristocracy and the clergy toward the poor.

No 79 Nada Nos ha visto (No One has Seen us)  Pobrecitas ( Poor Little Girls)

Pobrecitas ( Poor Little Girls)

“Yo es Hora” Capricios no. 80 ( It is Time).

\

Relieving us from this immersion in the wicked ways of the power elite, we enter into the installation of Dana Lynn Louis “As Above, So Below,” It is a site specific installation for the atrium of the museum, a space that resembles a greenhouse with its glassed in walls. Louis’s installation glass and mixed media sculptures change constantly according to light and weather conditions, time of day, or our own moods. It follow on her “clearing project,” which asked people all over thew world to “clear” themselves either spiritually or physically, but writing down these wishes and intentions on a piece of paper that was then burned.

Here we sense a different type of clearing, a more immediate clearing of the darkness of the other two parts of the installation with the lightness, both literally and metaphorically, of the suspended glass sculpture.

Ian Boyden is a great addition to our Northwest contemporary art scene. He is engaged and thoughtful, dynamic and motivated. Keep your eye on this museum for future exciting installations. UPcomin April 23 is Fragile Waters: Ansel Adams, Ernest H. Brooks II and Dorothy Kerper Monnelly,” until September 5. It will open on Earth Day.

Clearly this museum is going to be on our itinerary! You can combine your art visit with renting a bike and Island Bicycles.

This entry was posted on April 13, 2016 and is filed under Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.

Ritual Cleansing on Site of Murders of homeless people sponsored by SHARE/WHEEL

“I have made mistakes but I am so lucky with all the help, love and support I have been given since I moved here.” Young resident of the homeless encampment under I 5 and continuing up the side of Beacon Hill East of I 5 known with the derogatory term “The Jungle”

Climbing up the steep, muddy hill to arrive under the freeway at “The Jungle” where the murders had taken place of James Quoc Tran and Jeannie L. Zapata, as well as injuring of nine others, I was surprised to hear the regular sound of drumming. Perhaps they had already started the ceremony. At the top, I found no jungle, only a bare expanse of dirt under the 1-5 freeway. And the sound of drumming turned out to be the sound of cars on I-5 passing over an expansion joint directly overhead. The camp was small, many people had left since the murders, only six people remained.

One of them, a twelve year veteran named Michelle explained to me how she had started with a ministry to the homeless with her husband, but when he died twelve years ago, she became homeless herself.

Another quite young woman ( far left in photo above) claimed that she had made mistakes and her problems were her own fault, but that she felt incredibly lucky that people were giving her so much help and caring.

Of course, her problems are not simply her fault, they are the fault of a society that provides so little support and treatment options for drug addicted people. Apparently Tran was urgently seeking an out of state treatment program when he was killed. Three teenagers accused of the crime also lived in a homeless encampment, children of a drug dealing father and a mother who had lost custody. This is the bottom of our society, the result of our hopeless waste of money on war, and military, and free access to guns, in the hands of people struggling with addictions.

In spite of efforts to create a living room area with some cast off furniture and a community fire pit, the desolation of the encampment under the freeway overwhelmed me with sadness. The constant sound of cars overhead never stopped. See the expansion joint in this photograph.

The cleansing ceremony started at 12:30. Two native Americans offered blessings and real drumming in each direction, we read some passages about love and caring from Leviticus, and we spoke a two part chant of love and caring. Each of us was sprinkled with water from a cedar bough.

Two medical officials from King County attended. King County keeps denying funding to SHARE/WHEEL saying their outcomes are not good enough. In other words in our data driven world, you have to have statistically quantifiable results. SHARE/WHEEL encourages dignity, self respect and personal responsibility, not quantifiable results.

SHARE/WHEEL is a caring, creative organization that provides services to homeless people in well organized tent encampments that are run by the occupants, drug free and alcohol free. I joined the grant writing committee there for a while and was impressed with the intelligence and organization of the other committee members, all of them living in the tent camps or in the bunkhouse, another type of shelter also sponsored by SHARE/WHEEL. “The Jungle” is not one of their encampments but they offer support to all homeless people, honoring each time someone dies outside with a one hour silent vigil outside city hall.

Every winter solstice they honor all the homeless people who have died outside. The numbers keep escalating.

They also create rituals like the one I attended today, and

sponsored the Tree of Live in Victor Steinbruck Park, near Pike Place market. That sculpture has negative shapes referring to the fallen leaves of the homeless. All over Seattle you can see bronze leaves embedded in the sidewalk honoring homeless people who have died outside.

SHARE/WHEEL, an organization that for twenty five years has been providing a creative, caring, support to homeless people on their difficult path through life. We cannot allow them to go under with debt because of lack of financial support from our government or ourselves.

A Plea from their Website:

“We must demand that King County follow their own emergency plan, and fund SHARE. King County says they follow the “All Home” Plan (to end Homelessness) but they don’t. That Plan is clear – existing shelters like SHARE’s should be preserved, not bankrupted. Please immediately reach out to King County Executive Dow Constantine (kcexec@kingcounty.gov, 206-263-9600) and King County Community/Human Services Division Director Adrienne Quinn (Adrienne.quinn@kingcounty.gov, 206-263-1491) and ask them to fund SHARE! Please also call your County Councilperson today and insist on action.

At the same time please consider making an emergency donation to help keep us going while together we persuade the City, County, and Federal Government that SHARE is needed, and cannot be allowed to fail. The shelter system here is already full and simply would not be able to handle over 450 extra folks a night.”

This entry was posted on March 12, 2016 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Walid Raad Scratching on Things I Could Disavow

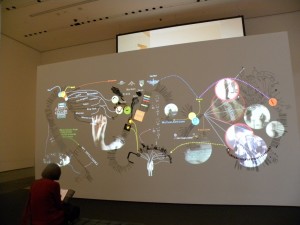

Walid Raad “Translator’s Introduction:Pension Arts in Dubai” 2012 paper cutouts, two channel video

Walid Raad experienced much of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-91) at long distance after he left Lebanon as a teenager in 1983 to attend high school and college in the United States. That distance forms the foundation of his work, his understanding that the construction of history is serendipitous, fragmentary, and heavily mediated. Research into archives is also questionable, because what survives in an archive is also accidental. Adding to this the distortions of trauma that are embedded in war and its experience, we have nothing but our imaginations and scraps of information to count on. Hence, Raad’s contention that distinguishing fact and fiction is beside the point. He claims that everything he says is factual, but there are different types of facts: emotional, aesthetic, historical, psychological.

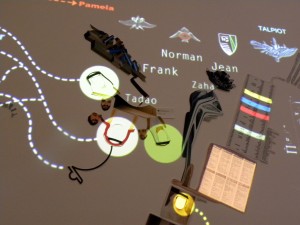

The installation and performance titled “Scratching on Things I Could Disavow” consists of several parts at the Museum of Modern Art, a computer projection or tableau as the artist calls it, which forms the backdrop of his performance, (see top of post)

a wall of large apparently blank colored squares of varying sizes,

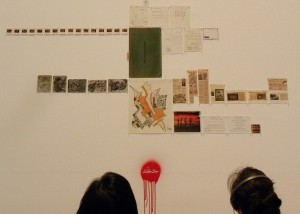

a wall claiming to examine art history in Lebanon with archival documents

a small scale museum with miniature images of Raad’s work,

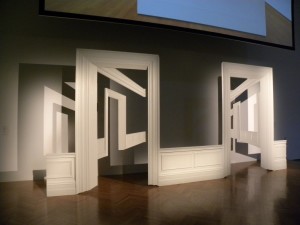

and the entrance to an empty museum “Views from inner to outer compartments”

Each of these components form a part of the narrative in Raad’s performance, which he claims refers to the construction of the history of art in the Arab world, as he puts it.

The largest and most complex component, is the wall projection “Translator’s Introduction: Pension arts in Dubai” It is this projection and performance that I will focus on here with briefer reference to the rest of the second floor installation at the Museum. (There is also a retrospective of his earlier work on the third floor component of this major retrospective.)

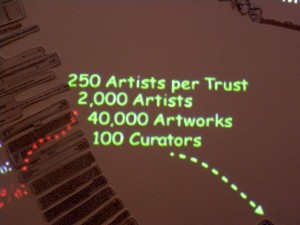

Raad’s narrative of the large tableau began with an account of the Artists Pension Trust, a real organization that signs contracts with artists who donate works to a privileged investment plan. (Prominent art historians are listed on its Advisory Board online).

But Raad’s real point is not this huge contemporary art collection, but the basis for the determination of value in contemporary art for such a fund. Who will buy the work and why? Financial investors need to have a basis for their decisions. He digs into its background and discovers that the tech workers of the parent company are former Israeli military intelligence officers. That company is owned by another company that combines risk management and algorithms: it analyzes data such as auctions, art language, and even color, in order to determine what affects the value of art.

The chilling result of Raad’s research is that the value of art is being determined by the use of a group of hedge fund experts in risk management. The sudden emergence of support for contemporary Arab art in the last ten years is embedded in this project. In addition to art work, the APT collects curators and art historians as advisors, who are well paid for their time. They create exhibitions and reassure investors of the value of the art.

In the tableau, these analysis are outlined in detail, with cut out biographies for about a dozen tech workers and their connections to the Israeli military.

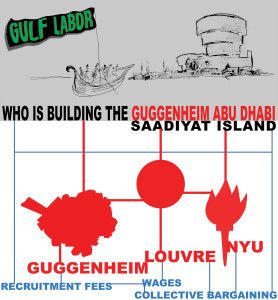

This arc is part of a larger arc that connects this intersection of art and money to the cultural explosion on Saadiyat Island in Dubai, where five institutions are being built to house gigantic collections of contemporary culture by five super famous architects. Dubai is investing in culture on a monumental scale. The cultural institutions include the Louvre, the Guggenheim, New York University, and, in collaboration with the British Museum, the Zayed Museum about the cultural history of the United Arab Emirates. Saadiyat, ironically, is very close to sea level, so it will certainly be flooded early in the rising sea levels that await our abuse of our planet, of which this mega “cultural” project presents itself as a dazzling example.

One has only to look at Gehry’s absurd design for the Guggenheim to see the inflated character of the project. The ludicrous design almost seems to be Gehry’s own joke as his response to this inflated, overwrought and contrived cultural endeavor.

The project on Saadiyat Island combines with high end hotels and other “amenities” (New York University! A golf course!) to present a complete “cultural” history and experience. The description of, for example, of what will be in the Louvre Dubai, is so vague as to be a parody of museum language and curatorial approaches.

In fact the whole project is a parody, and Raad’s performance is a parody of it as well. The crazy moving tableau suggests, as curator Eva Respini has amusingly suggested, a wild distortion and aberration of a flow chart, harking back to that early effort to order art history by Barr. But it is also, on some level, a frightening story.

Raad’s larger purpose is to call our attention to the ways in which contemporary art history and culture can be fabricated out of nothing, out of an empty sandy island. Another part of his installation speaks of how the colors (being analyzed for value, see above), are now hiding. We see a wall of seemingly empty squares, which are in fact, enlarged segments from publications, in which the colors are choosing to hide in the margins, to avoid their algorithmic fate.

Another segment presents a miniaturization of Raad’s entire career in a model of a contemporary art space in Lebanon, a huge space, unimaginably larger than previous spaces for contemporary art in Beirut.

His work, though, is shrunk to tiny proportions. Again, this is a psychological experience, based on anxiety about what is happening to Arab art. Finally, a wall appears with Arabic names one of which is splattered with red paint, a name of an historic artist which has been misspelled. Raad excavates his career from scraps of old articles, perhaps in an effort to begin a “real” history of Arab art. The last part of this segment of the exhibition includes an “entrance” to a museum, an empty museum, which we cannot enter, and Raad details how it prevents an Arab artist from entering.

But there is even more to this contemporary meditation on the history of Arab art in the Middle East.

Up on the third floor, a corridor and a single small gallery includes 3d prints of Islamic art from the Louvre, some of which is metamorphosing into Byzantine art before our eyes. These images are based on Raad’s actual research in the Louvre of the Islamic collection and his fantasy of what happens to this art when it is shipped to Dubai. It metamorphoses, it becomes something else.His installation includes 3d jet prints of objects from the Louvre. Part of the Louvre collection is destined to be exhibited in Dubai.

Raad’s fantastic installation, in the end, is a terrifying exposure of the interconnections of art, power, money, pretension, art investment, culture as a cloak for political aspirations, and of course, the invention of contemporary art history in the Arab world.

At the same time, if we look at it all in another way, we can believe that the Arabs are simply trying to counter their image as “terrorists” to suggest that they are cultured intelligent people with a history hidden in the middle of the oil soaked desert.

The Gulf Labor Coalition is exposing the slave conditions in which the workers who are building all of this culture are living.

Raad is part of the Gulf Labor Coalition, but has been banned from returning to the UAE. These activists expose in New York and elsewhere the abysmal gap between the treatment of workers and the pretentious arrogance of the cultural institutions and their elite brands.

Raad’s installation moves into the heart of Middle East politics, its inequalities, its wars, its culture, all in the form of a parody of museum installations.

This entry was posted on February 23, 2016 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in Beirut, Art in War, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.

The Museum of Modern Art and the Art of Disruption

I never dreamed that during my one month in NYC I would find myself repeatedly returning to the Museum of Modern Art for one show after another that provoked my ongoing analysis of art and politics as well as my long time interest in the way that the history of modern art is constructed particularly at MOMA. But that is the case.

Glenn Lowry Director of the Museum, spoke in a recent interview in the Brooklyn Rail of the role of the Modern Art Museum as disruptor, as having a history of disruption. Although that seems to be the trendy word in the last few years among the in crowd of “social process art”., Lowry actually cites Alfred Barr, the first director in his foresighted collection of film, architecture and design as well as his reaching out to art of Latin America, Asia, and Native Americans (certainly the latter is still a weak suit at the museum) as examples of disrupting the status quo. (Of course at the time the Museum of Modern Art was barely surviving on the largesse of Abby Rockefeller, so collecting in those areas was probably also a financial move, they were cheap and also easier during World War II).

Given that commitment to disruption, it is therefore not surprising that I have found in several exhibitions, as well as in odd corners of the museum, various disrupting displays. For now, I will put aside Walid Raad, the most obvious and complex example. I am planning to return to him in a separate post.

The first surprise was outside the café/restaurant on the second floor where we could see a Richard Serra video from 1973, Surprise Attack, (you can view the video at the link) in which he tosses a lead brick from one hand to the other. We might say, OK, we know his art from so many years, without paying attention. But someone discovered this early work and installed it. The reason: it is absolutely resonant with our political environment today.

Serra is reading from a text as he tosses his lead brick back and forth back and forth. The text is Thomas C Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict ( 1960). Schelling, a game theorist, writes about the “amplified threat of violence” that comes from failure to communicate with others and to understand them; for example, each of two armed people suspects the other will act first. While Serra doesn’t take it to the next step, he just keeps tossing his lead brick, it is obvious that we are there today, both in our homes (Serra/Schelling’s example is an armed homeowner and armed robber) and in international politics on every level. Of course, the US is always willing to play the bully these days, and skip the veneer of diplomacy.

Down in the depths of the education wing another surprise, archival materials from the well known radical group from Venezuela ” El Techo de la Ballena (Roof of the Whale).” Drawn from a donation to the Museum of Modern Art Library, the small exhibition of archival catalogs and photographs, with a video enhancement, lays out the radical left program of the more than sixty artists, poets and writers from Venezuela from 1961-69. It emerged during a period of democracy after a decade of dictatorship rule. They were energetically rejecting the dominant tradition of geometric abstraction in Latin America, (manifested in the universal constructivism aesthetic epitomized by Uruguayan Joaquin Torres Garcia, whose major retrospective appears on another floor of the museum.)

Here we have the intentionally messy, rude artists, aligned with Communists, protesting the status quo with ‘l’art brut” and surrealist approaches. The roof of the whale as a title refers to enormous power rising from the depths where it has been held submerged. They saw it as almost a volcanic power. Unfortunately, the show is a far cry from the volcanic energy the group proposed, set out in boring glass cases. A screen above highlights some quotes and images, but the real energy of the movement would be well served by a performance event with poetry readings in Spanish and English.

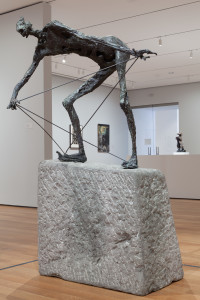

More prominently exploring a political theme, as well as the figure, “Soldier, Spectre, Shaman: the Figure and the Second World War” opened with a strikingly original sculpture by Maria Martins, The Impossible III 1946, a bronze in which two figures spar; aggressive organic appendages replace their facial features. The larger body seems to suck at the other, while the slimmer figure holds back, not surrendering, an image of conflict and unresolved aggression.

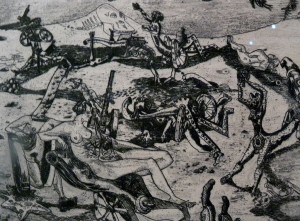

Nearby, in a small etching by David Smith, Women in War, 1941, a woman “reclines”in the foreground of a battle scene in which women are pursued, killed, raped. The image was printed in an edition of 16 and it follows his better known Medals for Dishonor series of 1937-40, but it is actually more unblinking in depicting atrocities of war.

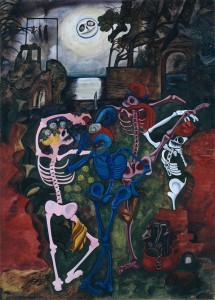

Still at the entrance, Edward Burra’s painting Dance of the Hanged Man 1937 ( the work here is in the Tate of Dancing Skeletons 1934 to give tstretching the chronology of the exhibition backward into the 1930s. Burra’s awareness of pain through his own life long disability, led to original and complex paintings about anguished suffering. The Dance of the Hanged Man shifts scales dramatically between the giant oppressors and the victims.

The main body of the exhibition includes a galaxy of sculptures by artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Jean Fautrier, Alberto Giacometti, and Joan Miro ( see top of post for Miro).

But Germain Richier’s savage and aggressive The Devil with Claws 1953 dominates the room.

Two intense groups of work are by Japanese artists. Shomei Tomatsu photographed people in the aftermath of the dropping of the bomb on Nagasaki, a place he revisited repeatedly during the American occupation : “What I saw in Nagasaki were not only the scars of war, but a never-ending postwar. I, who had thought of ruins only as the transmutation of the cityscape, learned that ruins lie within people as well.

Small etchings by Chimei Hamda, include Elegy for a new Conscript: Landscape 1953 (above) hard to look at in its immediacy. They reverberate with the artist’s memories of the horror of a soldier’s death in the desolate landscape of Northern China during the Sino Japanese war 1937-45 in which the photographer served as a conscript when he was a young man.

An intensely precise drawing by Mexican Francisco Dosamantes honors a dead soldier in the Spanish Civil War.

The show falls apart for me in the Shaman section, when it settles for East Coast based artists who are pulling from Native American spirituality. There are no native artists included, only one African American (Romare Beardon). Another artist who definitely did not belong was Henry Darger, one of my least favorite artists who seems to be so exciting to so many people. He creates private fantasies that have little to do with the heavy realities that the best work in this exhibition address. He is, not surprisingly, in the shaman section as well.

The strange inconsistencies of the selection are echoed in the subtitle of the exhibition, with its reference to the Second World War, in spite of the fact that several of the works predate it or refer to other wars. Why not the Figure and War, making the same point more emphatically, and skip the later shamans. The first two rooms of the exhibition are stunningly installed, selected and create a strong statement. I don’t understand why the exhibition didn’t stay focused on artists’ responses to the nightmare of the human body violated by war in the mid twentieth century.

Still, the number of expressive works that convey the horrors of war confirms that the museum no longer settles only for aesthetics. It wants to be responsive to our contemporary nightmares and demonstrate that artists have a role to play in revealing it, very much in the tradition of Alfred Barr. Rather than disrupting a tradition, the museum is actually reclaiming one. Barr favored the “Neue Sachlichkeit” artists and the grotesque until he became the director of the museum at the tender age of 27. In the 1920s Barr had already moved beyond Picasso’s cubism (and so had Picasso of course).

In 1936 under the duress of Hitler’s attacks on modern art, Barr invented the history of modern art with his “Cubism and Abstract Art Exhibition” and his famous chart, omitting all of his early digressions into grotesquerie.

The current impulse to disrupt returns to Barr’s young inclinations, before he was shaped by patrons, his own institution and politics. These shows, drawn entirely from the permanent collection, document a new willingness to disrupt genealogy as well as to embrace contradictory impulses.

The Pollock exhibition, all from the MOMA collection (and not all of what they have by any means), included many benchmark works, but again we see new perspectives. The Curator chose to give more in depth treatment to the forties ( this one untitled 1945), the transitions as they are called, allowing us to see the bizarre hesitations, rather than simply settling for a grand progression to the final drip paintings. Also the ongoing of Thomas Hart Benton’s principles of organization are obvious if you know what to look for. Pollock always said he rejected Benton, but it isn’t true.

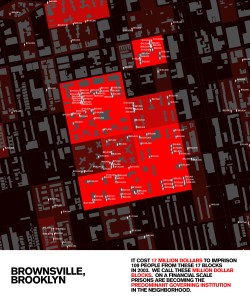

Likewise In “Scenes from a New Heritage” the reinstallation of the contemporary collection, some surprising work pops up, particularly “Mapping Justice. ” by a team of artists based at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture that documents the 17 million dollar cost of imprisoning 19 people from 17 blocks in Brooklyn, so called “Million Dollar Blocks.”

Nalini Malani’s Gamepieces layers mythology with contemporary violence, in her trademark circling acetate spheres, painted with figures that move like an early movie across the wall. Camille Hernot’s film Grosse Fatigue tells the story of the creation of the world juxtaposing contemporary technology and historical archives, playfully, provocatively, tragically. Huseyin Alptekin’s photographs of cheap Istanbul hotel signs made sense to me because I have known his work for many years, but I doubt anyone else got his larger point of class and power issues.

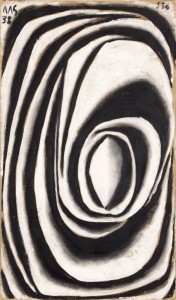

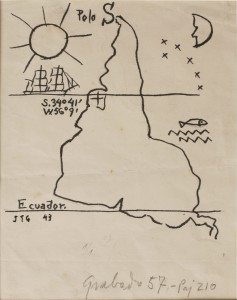

I can’t leave out the Joaquin Torres-Garcia retrospective, since it is the first showing of this great modernist’s work since I assisted with a retrospective in 1970 in my first job as curatorial assistant to the late great curator/director Daniel Robbins. A lot of Torres Garcia’s work burned in a fire in Brazil in 1976, not long after our exhibition, but thankfully the Museum of Modern Art curator, Luis Pérez-Oramas has been able to put together another stunning show of this pioneering artist, teacher and philosopher. This Uruguayan artist influenced artists all over Latin America. The fact that he is not mainstreamed in art history is ongoing eurocentrism. This exhibition is a glorious retrospective including his earliest street art and peculiar murals in Barcelona, his books, his toys, his constructive sculpture. His brilliant inverted map of South America proclaimed Latin America as a center of culture.

Finally, that crazy Katerina Fritsch sculpture in the garden parodies Rodin’s Burghers of Calais, but not just to be funny. Take a close look and you see some scary ideas. MOMA this January was really a disruptive place and I loved it.

Photo Credits:

Edward Burra, Dancing Skeletons, 1934, gouache and ink on paper, 78.7 x 55.9 cm, Tate Collection.

Shomei Tomatsu (Japanese, 1930-2012). Hibakusha Tomitarō Shimotani, Nagasaki. 1961. Gelatin silver print, 13 × 18 3/4″ (33 × 47.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist © 2015 Shomei Tomatsu

Laura Kurgan, Eric Cadora, David Reinfurt, Sarah Williams, and Spatial Information Design Lab, GSAPP, Columbia University. Architecture and Justice from the project Million Dollar Blocks (detail). 2006. Digital prints and Powerpoint file with images generated from Esri ArcGIS (Geographic Information System) software. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designers, 2008. © Laura Kurgan, Spatial Information Design Lab, GSAPP, Columbia University

Nalini Malani (Indian, born 1946). Gamepieces. 2003/2009. Four-channel video/shadow play (color, sound: 12 min) and synthetic polymer paint on six Lexan cylinders. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Richard J. Massey Foundation for Arts and Sciences, 2007. Photo by Thomas Griesel. © The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Joaquín Torres-García (Uruguayan. 1874–1949). América invertida (Inverted America). 1943. Ink on paper. 8 11/16 × 6 5/16″ (22 × 16 cm). Museo Torres García, Montevideo. © Sucesión Joaquín Torres-García, Montevideo 2015.

Joaquín Torres-García (Uruguayan. 1874–1949). Forma abstracta en espiral modelada en blanco y negro (Spiral abstract form modeled in white and black). 1938. Tempera on cardboard, 31 7⁄8 x 18 1⁄2” (81 x 47 cm). Private collection. © Sucesión Joaquín Torres-García, Montevideo 2015. Photo ©2015 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Christian Roy

All other photos by Susan Platt or Henry Matthews

This entry was posted on February 20, 2016 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Uncategorized.

Abounaddara and Syria Freedom Forever: Making visible the ongoing tragedy of Syria:

I am reporting here on two online sites that are actually speaking from the ground in Syria, the receivers of this tragic onslaught. The statement just above is an excerpt from Abounaddara‘s manifesto.

To begin with, here is just one post from Syria Freedom Forever detailing a recent attack that makes what is happening in Syria specific and real:

“On Sunday the 13th of December, 2015, Douma and surrounding towns were subject to 59 indiscriminate aerial attacks, as well as a large number of cluster bombs. The preliminary death toll is 38 civilians, including 9 children and 5 women, according to figures provided by the Syrian Network for Human Rights. This number is likely to increase as crews continue to search for victims under the rubble. Schools in Douma and Zamalka, as well as a medical centre were targeted in the attack. This, in an area which has become almost devoid of medical care due to constant shelling.”

Syrian videographers and grassroots activists communicate to the world how they are living and working in the midst of the relentless Civil War that has them surrounded by violence on all sides.

The news media here repeat over and over that “we” are “fighting” this “terrorist threat” and that “everyone” is “terrified”. The reality is that most of us are not terrified, we are going on with our comfortable, well fed lives. The people who are terrified are the people on the receiving end of the hundreds of bombs we are dropping. That is terror.

Drawing of bombs falling down from five countries, Isis to the right beheading someone. One child is holding a Syrian flag and the other has a thought balloon says “freedom”

When Paris and San Bernardino experience a terrorist attack, that is truly frightening, but the people in Syria, in particular, experience that constantly from our bombs, from the Syrian government, from Isis, from other gangs of thugs in Syria, now also

from Russia and Great Britain.

At the same time they are continuing to resist oppression, sending us information, holding marches, speaking out. This resistance is not reported in the media and not supported by any outside assistance.

What Justice? still from film, speaker sits for a full minute in silence and then says “He has to die.” He is not even an animal, they kill in a noble way.”

Abounaddara is a collective of anonymous videographers who post 4 minute clips every Friday. Each clip interviews an individual revealing their personal perspective, or follows someone in their home, or reports on a concert or some other act of creative resistance. In speaking with individuals they reveal the complexities of the situation.

For example in “No Exit” a young filmmaker speaks first of the participants in the revolution bringing together very disparate people, and particularly in prison real criminals are thrown together with children, truck drivers and political criminals. Then he speaks of the contradictions of both Isis and Assad tolerating people who oppose them, until they decide one day not to and kidnap or kill them. There is no clear line of right and wrong, of good and bad, of winning and losing anywhere in Syria.

Abounaddara has recently been praised by the art world, and included in the Venice Biennale.

This Fall, the Vera List Center for Art and Politics in New York gave Abounaddara an award, an exhibition and a symposium.

They are a sophisticated group of artists, theoretically literate who are tired of what they call “televampirism” of the news, the representation of victims and its perpetrators.

The grizzly images of dead bodies become what they refer to as “the banalization of evil.” (Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase) They feel that “television can inform while respecting human dignity.” They resent anonymous social media with “low informational value” gobbled up by the international press. Abounaddara believes that those taking these images are motivated by “revenge” and provide a “voyeuristic” view of violence.

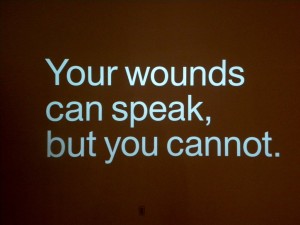

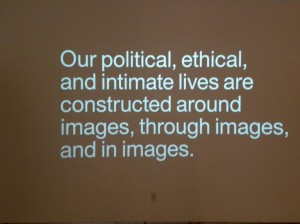

They claim “The Right to the Image” they seek to “Stop the Spectacle’. They believe that “The persons whose humanity is suppressed in images from wars, mass violations of human rights and other similar situations are not allowed to speak. Their humanity stops at the rights of bystanders to freedom of expression . . . Your wounds can speak, but you cannot.”

I was fortunate to see the last segment of their exhibition in New York. While all of the videos are online to view, the curated selection in New York juxtaposed three videos at once on different walls of the gallery. Surrounded by the large projections in a public space magnified the experience.

The videos sometimes had little or no dialogue, only actions, frequently it was a single person speaking. The political positions of the speakers varied, Alevi, resistance fighter, ordinary person, government prisoner, ISIS detainee, sniper, musician. In each case, as the person spoke, or moved about their home, or described their experience, or stated their opinion, they spoke with dignity. It was deeply moving.

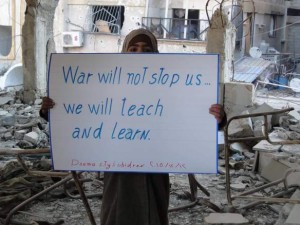

Somewhat similar in intent, although less embedded in theory, are the tactics of the resistance blog

We see individuals on the ground holding signs and drawings about their situation. They are communicating directly with us. As more and more countries decide to bomb Syria, and more and more people leave, these are the people, men, women, children, elderly, who are still there, on the ground. They are surviving, but they want our support. The support I am giving today is to write about their condition.

Schools are bombed, bakeries are bombed, civilian homes are bombed. Markets are bombed.

These two projects enable people in the midst of the Civil War to speak for themselves.

And then we have the issue of refugees and our hostility in the US to giving shelter to those who are trying to escape. As of November 17 there were 4.3 million Syrian refugees. Turkey as over half of them. Lebanon another million, Europe 680,000. Canada is welcoming them. Obama has suggested 10,000, as ignorant politicians encourage people to refuse them.

As the media, across the political spectrum, (with the exception of the non commercial Democracy Now and a few other alternative sites), repeat over and over, that we are afraid, we are concerned about terrorism, it fans the flames of the fear of all Muslims, all others. Racism toward all nonwhite people is escalating.

Lack of gun control is obviously the single most lethal source of danger in the US.

But, in reality, if we were to allow people here to speak for themselves, as individuals, as Abounaddara does in Syria, we would discover many more complex feelings than simply “fear”.

If the images from Syria Freedom Forever were posted every day on the front page of newspapers, or blogs, everyone would agree that more aggression toward the Middle East is useless, cruel, and obscene.

This entry was posted on December 16, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art in War, Syria, Uncategorized.