“Not Vanishing: Contemporary Expressions in Indigenous Art, 1977 – 2015”

Note: this post is dedicated to the Colvillle Indians who have just had a devastating loss of timber from this summer’s forest fires

The title “Not Vanishing: Contemporary Native American Art 1977-2015, curated by Gail Tremblay and Miles Miller at the Museum of Northwest Art in La Conner, Washington, obviously turns on its head the cliché of “vanishing races” applied to native groups from the turn of the 20th century. Edward Curtis embarked on his well-known photographic project of preserving them through photography at the time when assimilation and extermination were the ongoing policies of the US government.

This ambitious exhibition (lasting only until January 3) includes 78 works of art by 49 artists from 23 tribes in the Northwest, extending North into Canada and Eastward to Idaho and Montana. We are invited to look closely and think carefully at the many trajectories of the art work that point to layers of meaning and interpretation.

Featuring both well-known and emerging artists, the exhibition fills the Museum on both floors and embraces us with many voices. I can only touch on a few artists and ideas here.

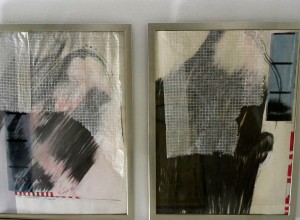

At the top of the post, and here, is the work of Rick Bartow, an intense expressionist multimedia artist. This painting, called Going as Coyote, is carefully described by curator Tremblay in her essay:

“one immediately notices the way the artist divides the picture almost in half, the right side, dark, and the left filled with color and light. To the left of the center, the artist’s body leans forward toward the light and seems almost illuminated against the dark half of the drawing. . . .. He draws his own face with mouth open and teeth revealed. The top of his head transforms into a dark coyote face, also with teeth bared. The coyote’s ears are light and brightly colored.

“The artist portrays himself as a dancer, and carries the two dance sticks that define the front legs of an animal when one performs the role of that animal in a ceremony. In this drawing, he portrays the tension of existing in two different realities.

“In front of the artist is the dark shadow of an arm reaching into the light. It does not carry a dance stick but reaches like a third appendage into a space filled with hand and finger prints that as they rise transform into coyote tracks so the human marks of the dancer visibly merges with coyote, as dance and coyote face a space illuminated by all the colors of day …”

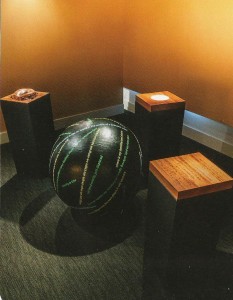

Tanis S’eiltin’s installation, Territorial Trappings, 2012 epitomizes the theme of the exhibition, the mixture of indigenous perspectives and contemporary art, native values and pressing environmental issues that affect us all. S’eiltin’s theme is Native ties to the fur trade that continued right into her childhood.

Fashions such as fur hats made from sea otters, or fur jackets from lynx hides directly benefited the livelihoods of indigenous peoples, but also impacted their traditional relationships to the natural world. The ambiguity of this economic trade-off is suggested in the gallery with a neon sign reading “Trade” backwards.

John Feodorov has always been fascinated by the role of white “spiritual” practices that co opt native spirituality, as well as recognizing contradictions within native culture itself. He describes his installation Domi-Nature:

“Domi-Nature is comprised of 12 white-washed Teddy Bears kneeling and praying silently before a projection of the three smoke-stacks from the Navajo Generating Station, a coal-fired power plant located on the Navajo reservation. The bears genuflect as if before a vision from heaven. This is an updated version to an earlier installation I created in 2001, just before the terrorist attacks on 9/11. Since then, this piece has taken on a more serious and tragic association for me, particularly with recent environmental tragedies such as the BP Oil Spill and the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima Japan.”

These two installations address environmental concerns from sharply contrasting perspectives, but both refer to the artist’s sense of urgency as well as the complexity of the relationships of native artists and the environment. While Indigenous artists and activists are taking a lead in protesting environmental destruction and climate change, others are working for those companies or encouraging and inviting power companies onto their land for desperately needed jobs.

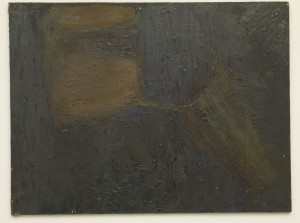

Another artist who is acutely aware of these contradictions is Joe Feddersen. As a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes, in Eastern Washington and Southern Canada, Feddersen brings together stunning technique with subtle, but strong statements ( this image does not do justice to his exquisite work, the black verticals are a reflection of the photographer!). He worked for power companies earlier in his life, and you see on some of his work the geometric abstract form referring to those giant electrical transmitting towers. At the same time, those same towers carry energy from the Grand Coulee Dam, which destroyed many fishing grounds of the traditional Colville during its construction and subsequent flooding.

That tale is narrated from the perspective of his own family in Lawney Reyes’ book B Street. How the building of Grand Coulee Dam Changed Forever the Lives of One Indian Family and Devastated an entire tribe.” (University of Washington Press, 2008) A “Dreamcatcher” by Reyes is included in “Not Vanishing”, and an outstanding example appears in Seattle on Yesler and 32st as an homage to his sister and brother (the famous activist Bernie Whitebear).

The exhibition purposefully includes a range of media that range from weaving, beadwork, and carved cedar boards (here in John Hoover’s beautiful Loon Dance) to non native traditions of printmaking, acrylics, glass and bronze. These standing guardian figures by Joe David and Preston Singultary are made from blown and sand carved glass.

Often the works mix traditions and aesthetics, as in the entire room of extraordinary glass work by well known artists Joe Feddersen, Lillian Pitt, Preston Singletary, Caroline Orr, Susan Point, and others. That room epitomizes the cross cultural sophistication of these artists, as they work in a non traditional material but imbue it with both indigenous references and forms, as well as contemporary issues.

For example Lillian Pitt’s extraordinary Shadow Spirit in the Grass, draws on both indigenous meaning and contemporary ideas with cast New Zealand lead crystal and metal. Part of a series called “Shadow Spirits,” it is, as Tremblay writes, “cast by making a mold around a clay sculpture she created for the purpose.” Embedded in the clay are natural materials; here the imprint suggests a navel that “marks the connection between humans and the generations that precede them and make their lives possible.”

One of my favorite younger native artists included in “Not Vanishing” is Wendy Redstar. Her work humorously plays with the clichés about Indians, even while she makes a deeper point. At the time of the Seattle Art Fair this summer, Redstar installed numerous life size hunting decoy animals in Volunteer Park, a witty comment on one aspect of our contemporary interaction with nature. In this exhibition, her small car with the long title in two languages, iilaalée = car (goes by itself) + ii = by means of which + dánniiluua = we parade plays with contemporary perspectives on ceremony and indigenous identity.

Gail Tremblay and Miles Miller, the curators of the exhibition, fortunately included their own work as well.

Gail’s Exploding Star created by the painful technique of weaving with metal thread, refers to environmental issues as well as mythic traditions. In fact, in her introductory talk to the exhibition, Gail explained the work in terms of historic myths, but in her wall statement she spoke of “ materials we have ripped from the Earth who sustains our lives.” In other words, she connects the ancient and the contemporary in both the imagery and its significance.

Miles Miller, best known for his beadwork, here contributes two large prints “The Traditionalists” that speak of the Lewis and Clark expedition and its absurd misunderstanding of the native tribes that it met on its way West. He enumerates both their invented place names, as well as the anguish of the natives perspective.

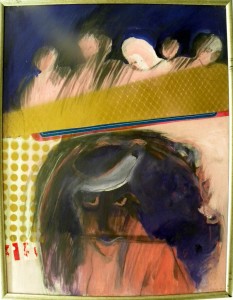

“Not Vanishing” can also be analyzed from the perspective of mainstream art history styles: expressionism in drawings and paintings by Rick Bartow, James Lavadour, Jaune Quick to See Smith, and Sara Siestreem’s John Day Narrows here,

affiliations with Robert Rauschenberg in

the provocative imagery by Corky Clairmont, here, in his Split War Shield made from cast handmade paper that looks like tire tracks.

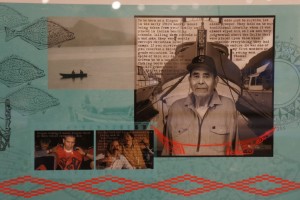

or the references to “pop art” in the amazing tribal masks from automobile parts by Larry Beck, to minimalism by Joe Fedderson in his reductive geometry, to realism in Larry McNeil’s poignant homage to his father

as well as the photographic realism of Matika Wilbur’s project redoing Edward Curtis (see my previous blog post about her work). And then, of course, there is the fact that Native artists practiced abstract art for centuries before it was “discovered” in Europe and the “American Abstract Expressionists.”

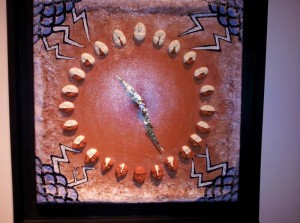

Erin Genia’s Blood Quantum Countdown affiliates with conceptual art as it poignantly points to why these artists so urgently sustain their cultural heritage in the midst of their immersion in the contemporary world. She explains: “Blood quantum originated during a historical period of the U.S. when Native Americans were viewed as a vanishing race. Today, it enjoys widespread use by tribal and federal governments as a legitimate method of determining whether a person can be considered an American Indian. This piece warns that continuing its use inevitably leads to a countdown to our extinction. . . Our survival as a people is based upon a whole spectrum of qualifying factors, from lineal descent to connection to our tribal communities, to protecting, preserving and revitalizing our tribal cultures. It’s time to reassess the viability of the blood quantum system.”

Indeed, the theme of “Not Vanishing” is exactly that, these artists in many ways are demonstrating the complexity of contemporary Indigenous art. The exhibition provides us with a window into what might be possible if the history of American art could be more truly inclusive. Like the exhibition “Our America” that focused on contemporary Latino/a art, this exhibition exposes a rich history of contemporary art that does not surface in the mainstream of art history except for token examples.

Living in the West, in the midst of dozens of contemporary tribes, all of them producing contemporary culture, I am acutely aware of this omission. When I go to DC a visit to the National Museum of the American Indian, right on the mall, is often at the top of my list. But when I speak of that museum to other art historians living there, they have never been there except perhaps to eat. This tells us a lot about marginalization.

Unfortunately, there is no printed catalog of this exhibition. There is a lot of written material which I understand will be posted on the website of the Museum of Northwest Art. Gail Tremblay’s powerful essay provides an historical trajectory for both traditional attitudes to indigenous art (heavily ethnographic), the stimulus of the 1930s Indian Arts and Crafts Act, as well as the Institute of American Indian Art, and one source for contemporary art history in the Northwest at the Sacred Circle Art Gallery in Discovery Park in the 1990s. At that venue, curators Steve Charles and Merlee Markstrum created a series of strong exhibitions by contemporary native artists. As a critic, these shows introduced me to several of the artists included in “Not Vanishing”.

The exhibition in La Conner, unfortunately rather distant from Seattle, ought to be at the Seattle Art Museum, or travelling to a major city. The fact that it is in a hard to reach museum, and has no published catalog, demonstrates that the struggle to integrate contemporary American art has a long way to go.

This entry was posted on November 24, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, indians, Indigenous activism, Indigenous Art, Photography, teddy bears, Uncategorized.

Nato Thompson Seeing Power, Art and Activism in the 21st Century

“My hope is that this book will help readers take stock of the capacities and resources of everyone involved in order to construct worlds collectively. Building new worlds requires patience, compromise and conviviality. It is a process of working in the world and with people.” Nato Thompson in Seeing Power, Art and Activism in the 21st Century, Melville House, 2015, 165 pp.

In this brief book, almost a manifesto, Thompson leads us to concepts that enable artists to intervene in the capitalist system without being co-opted. He starts with Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer (the conservative elitists of the Frankfurt School) who warned against mass culture (Thompson does not mention that their impetus was their horror with Hitler’s success in using mass media.) Adorno’s ideas were familiar to Clement Greenberg’s in New York City in 1939, as he was formulating his “avant-garde and kitsch” essay that obliterated the socially engaged, politicized and revolutionary culture of the 1930s. Thompson’s reference to Adorno sets the stage for his concern that capitalism co- opts culture. Of course, Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht also from the Frankfurt School, were offering the opposite argument, that mobilizing the masses to revolution could be realized through mass culture. We have certainly see that today with social media!

Thompson touches on the historical background of 19th century materialism and industrialization as the foundation of the culture industry, the production of products to be consumed, and its implications for the production of art, then turns to his crucial theme: the long running critical debate on art and politics. Thompson comes up with two terms “ambiguity” and “didacticism” as a way of delving into the issue. One can translate these terms into aesthetics and politics, of course, but ambiguity and didacticism suggest the problem more obviously, that artists who rely on aesthetics avoid direct statements, and artists who rely on direct politics alienate us with preaching.

Of course the whole argument is a red herring, in my opinion, if you take the position, as I do, that all art is political. The question is what is the engagement of the artist with the issue, is it superficial, self-aware, or profound? For example, Thompson went on the road with Jeremy Deller for his “Conversations about the Iraq war.” (Although not acknowledged, the piece was sponsored by Thompson’s Creative Time organization). Deller is a white British artist. He knew a lot, he engaged Iraqis and US veterans in the project. He became known in the first place for a film that recorded a recreation of a miner’s strike. But his primary interest is spectacle itself as clearly revealed in his pavilion at the 2013 Venice Pavillion.

Thompson provides a breakneck overview of the second half of the twentieth century, including Guy Debord and the Situationists, as well as the Beat generation. He omits at this point the radical revolution in art produced by artists affected by AIDS as a primary moment when the shift to political art began (he does mention it finally near the end of the book as an example of political art that “gained momentum by the sheer political imperative: friends and lovers were dying.” A newly opened exhibition at the Tacoma Art Museum, “Art AIDS America” examines in depth the ways in which art about AIDS shifted the trajectory of formalist American art. I will be reviewing it shortly on this blog.

Thompson identifies two types of production that connect art and politics successfully “social aesthetics,” based on personal relationships and “tactical media” which recognizes “power in every aspect of life” and “disturb[s] political structures.” He groups Judy Chicago, Suzanne Lacy and Meirle Laderman Ukeles together as second wave feminist examples of “social aesthetics,” the only reference to feminism in the book. The example for “tactical media” is the Critical Art Ensemble, who moved outside the art world to larger systems of power. The Yes Men are, of course, another great example. Paul Chan’s project in New Orleans “Waiting for Godot,” (also sponsored by Creative Time) is discussed at length by Thompson, as an example of successful “social aesthetics.” That is the only time that African Americans are given a voice in the book.

While many chapters recount all the ways in which capitalism and the culture industry make it difficult for artists to act outside that system, his conclusion focuses on the idea of creating space for actions, such as occupations that address the issues that concern us, “ rent control, housing, minimum wage, child care…” His citation of Trevor Paglen as a model of this emphasis resonates with me. Paglen as a geographer who also holds an art degree has long been a radical pioneer in intervening in public spaces, both conceptually and through photography.

Nato Thompson’s book documents the capitalist morass that confronted him as an elite young white curator of the 1990s. At some point, he woke up to the possibilities for art to intervene in systems of power. But, he carefully avoids specific political ideologies entirely or even their terminology, such as revolution, class, dialectics, or even Marxism, Communism, Socialism, Anarchism. Perhaps he was afraid of being “didactic.” He also fails to explore the work of artists of color, which is intensely political. Instead he quotes well-known theorists like Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Antonio Gramsci, and Slavoj Žižek. His call to action, cited at the beginning of this review, calls for “patience, compromise and conviviality,” terms that are pretty weak as a means to realize the power of art to change the way people think. His more productive idea is in the preceding sentence, the idea to “construct worlds collectively.”

When Thompson states on p 23 that the activism of the WTO ‘”ended” during the Bush years, I was surprised. I have written an entire book on the subject of Art and Politics from 1999 – 2009, and barely scratched the surface. It was, in fact, an era of passionate oppositional art that specifically addressed political issues. It actually died when Obama was elected, but happily, it is now returning to the fore, and might even be said to dominate the art world. Creative Time itself has also evolved into a dynamic and exciting place to consider art and politics. What could have been more confrontational than inviting Amy Goodman to be keynote speaker at their recent conference in Venice.

What we really need, and we are getting closer to it all the time, is to stop even discussing “problems” with politics in art and support artists, who, creatively frame condemnations of capitalism, globalism and war. With climate change a reality, we can’t afford to be “patient” or “convivial” anymore. I am not as concerned about capitalism corrupting art, as I am concerned about capitalism ending the world as we know it.

Artists are already contributing to making that reality visible. Our critical responsibility is to make sure their actions are acknowledged and supported that they are encouraged to be understandable as well as aesthetic. Art and politics joined together offers a vast range of possibilities to confront the system.

This entry was posted on November 5, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, democracy.

A visit to the home of contemporary Turkish Artist Tomur Atagök

During my recent trip to Turkey, I was fortunate to spend several days in the home of the contemporary Turkish artist Tomur Atagök. By immersing myself in her environment, and living with her art, I gained new insights.

She had recently reinstalled the art in her home, following her major retrospective exhibition this spring.

While I was there, we heard in detail about the intense migration from Turkey to Greece, as well as nationalists burning several offices of the HDP ( Halkların Demokratik Partisi -People’s Democratic Party), and much more from the perspective of both Turkish newscasters and others in Europe and elsewhere in the Middle East. We interspersed intense news with popular culture, classical culture, and nature programs, in a parallel to her own art, which combines intense concern for current issues engulfing Turkey with commentary on popular culture, particularly as it affects women, and agony over the destruction of the environment.

Tomur lives in an idyllic compound in what used to be far out in the country, but which today is increasingly threatened by development, both government sponsored and local high end condominiums sprouting up in her small village.

While the compound where she lives still maintains an immersion in nature, we sometimes heard the not so distant boom of dynamite blasting away hills.

Since moving to Kumsuyu in the 1990s, her work has included references to the fragility of nature. She deplores our lack of respect for the natural environment, and sadly, that is only becoming more obvious each day, as the megalomaniac plans for the new airport, its highways, its storage facilities, and the third bridge destroy many acres of formerly protected forests along the Bosphorus, the only remaining forests near Istanbul, “the lungs of the city.”

What struck me, living with her art on every wall, and waking up inches from these two paintings, was her extraordinary sense of traditional lush brushwork, color and paint that she has chosen to imbue with strong contemporary references to political issues, literature, feminism and nature. I can only touch on some of her work here. Gray Nature here combined painting with sticks to suggest a fragile, disintegrating balance.

Her references to women range from Neolithic goddesses to the wives of military dictators to contemporary pop singers, sometimes all in one painting. One theme is ‘ordinary women” . In this series in her staircase, called ” Open the curtain slowly,”fabric covers the subtle reference to a woman

Born in Istanbul, she grew up in a family that was part of the secular military, but she also has ties to what she calls the matriarchal traditions of the Caucasus. She attended art schools in the United States during the late 1960s where she intensely responded to Professor Dale McKinney at Oklahoma State University and quickly grasped the principles of abstraction through the lens of Hans Hofmann’s well known theory of push-pull. She initially painted in dark tones as in this work, Shadows on the Wall of 1960.

She went on to study art at the University of California, Berkeley in the midst of the free speech movement and flower children, where her palette began to brighten, then on to the University of Washington, finally returning to Turkey in 1973 where she began moving beyond abstraction to become a pioneering feminist artist (as well as an historian of women artists in Turkey.) In 1985 she created this work, Followers, commenting on the situation for women after the military coup of 1980. This painting was on the staircase also as a prelude to “Open the Curtain Slowly.”

Since the 1980s she has filled her paintings with references to pop stars and contemporary women, as well as to the corruption of nature with plastic and other trash.

And perhaps her best known theme, the ancient Anatolian goddesses,

as an historical counterpoint reference point for women today.

All over her house were simple gestural art works that incorporated nature as well as the trash we leave behind. This series was called Framed Nature. Her training in abstract gestures is now materialized as gestures created by sticks, wire, and other natural materials. These works hung in her living room.

In the hallway were “art boxes,” large boxes with an assortment of trash that she has picked up.

She often combines collage, textiles, sticks, bugs, spent bullets, in small free standing sculptures and boxes. I found a huge dead fly that she added to her collection for another artwork.

This impulse to make collage extends into thousands of “diary pages” made from the wrappers and tickets of her own life,

as well as textile collages created from fabrics that are personal to her life. She generously gave me two. Here is a detail of those textile collages, note the antique collar at the top of the right hand collage. The piece below that is actually gold fabric, and below that a hand embroidered antique fabric.

Here it is installed in my living room in Seattle (with the antique collar visible on the top left).

Tomur has created hundreds of art works in her prolific career, works protesting war, honoring important writers, celebrating popular culture. But the dominant theme of the works installed in her home today is nature, as it is outside her window, and as we are acting on it with all of our carelessness.

This entry was posted on October 19, 2015 and is filed under Contemporary Art, Feminism, Turkish Women Artists, Uncategorized.

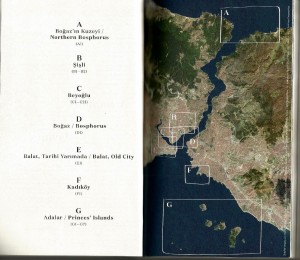

“Tuzlu Su” “Saltwater” Istanbul Biennial 2015

Against the backdrop of Turkey’s intense political realities, horrifying bombings at peace rallies, and other acts of violent nationalism, as well as an urgent migration crisis (as it opened, we witnessed on television thousands of desperate refugees leave Bodrum on the coast of Turkey packed onto rubber rafts for a four hour trip to Kos and Lesbos, (nearby Greek Islands).

“Tuzlu su” “Saltwater: A Theory of Thought Forms,” the 14th Istanbul Biennial, appears innocuous. It features mysterious venues that cannot be seen, installations in obscure cisterns, former bank vaults, and about to be torn down garages and houses, as well as trips to the Sea of Marmara Princes Islands and up the Bosphorus to simply view a lighthouse with a Lawrence Weiner graphic image and a Cold War radar antenna.

Under the Sea of Marmara, entirely invisible to us, Pierre Huyghe’s “Abyssal Plain. Geometry of the Immortals” located near the inaccessible island of Sivriada, is a “concrete stage …around existing rock formations on the bottom of the Sea of Marmara….over the next few years it will become a platform for objects taken from the surface, production left over from the history of the Mediterranean region, including the artists own production.” Through the power of natural currents, the existing creatures of the sea will join the human artefacts on the “stage.” More about those currents soon, they are a major feature of the Biennial.

Not invisible but inaccessible was Fusun Onur’s fishing boat with loudspeakers with a recording of a woman reciting passages from the Odyssey. As you see below, Füsun Onur’s house is almost in the Bosphorus, and her entire life has been spent very close to it, so she has always had a relationship with it unlike any other.

The Istanbul Biennial this year is an exhibition of cloaked intent.

Just as the Bosphorus itself hides histories of wrecks, and unimaginably early settlements only recently discovered, so this Biennial hides its urgent politics and radical thinking. Only by close attention and excavation does the urgency of the exhibition become clear.

The Biennial includes a total of 1500 artworks in 36 venues; it was impossible for anyone to visit all of them. I chose to view the larger exhibitions, and a selection of art on display in houses, galleries, boutique hotels, and other venues in the center of the city, all of them privately sponsored spaces, a significant aspect of the cloaking of the Biennial from government scrutiny.

The intent of the organizer, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, who refers to her role as drafting a “Composition,” takes on the metaphor of saltwater as a synonym for “transformation and change on the planet . . .It is a theory of life. “ Christov-Bakargiev does not believe in separating art and science, of creating boxes for different types of thinking. Flow of water is equated in her mind to flow of ideas, waves to waves of resistance and outrage, knots to arrested movement. She sees art as an empathic political statement in conflict with art as capitalism. (Here come the cloaked politics.)

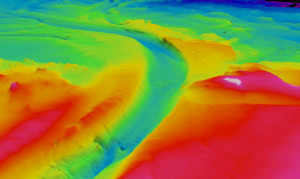

As a result, she included physicist William Irvine who explores knots inside water, and oceanographers Emin Özsoy and Jeffrey Peakall who study underwater rivers as part of “The Channel,” a segment of the Biennial located in the Istanbul Modern Museum.

A stunning video of the Bosphorus, taken by a submarine, demonstrates the enormous power of an underwater river flowing into the Black Sea, in the opposite direction from the surface flow. For this Biennial it stands as a metaphor for a powerful, but hidden, form of resistance to the surface of society. The deep grassroots activism of artists can change the course of the social forces of society in the view of Christov-Bakargiev. She believes that all art is political.

Christov-Bakargiev erased as many borders as she could, media, time, place, genre, political, aesthetic.

She is inclined to the mystical as well as the scientific, particularly to those who make the invisible into abstract expressions, so she included drawings such as the familiar “thought forms” of Anne Besant and Charles Leadbetter, as well as images created by physicist Giovanni Anselmo,

neuroscientist Santiago Ramon y Cajal (above) , the mathematician Fredrik Carl Mulertz Stormer, then continuing to the present with Lawrence Weiner’s calligraphic gesture and Liam Gillick who painted the formula known as Bernoulli’s principle that as pressure decreases, speed increases on the outside of the Modern Museum.

Visual work by writers, like Orhan Pamuk’s notebooks with watercolor sketches, also crossed media boundaries. Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, another Biennial site, literally materialized his novel of the same name, displaying artifacts of the lives of 1950s and 1960s elites, organized by the chapters of his novel and obfuscating fiction and reality. The entire collection inside, randomly collected by Pamuk was attributed to the fictional family of the novel. As he collected the artifacts, it also stimulated what he wrote.

“The Channel” galleries of the exhibition, near the entrance, encapsulated the flow of metaphors in “Tuzlu Su” as a whole “representing both the Bosphorus and the ‘sodium channel of our neurons, a passageway in the membrane of these cells that lets only sodium ions pass through.”

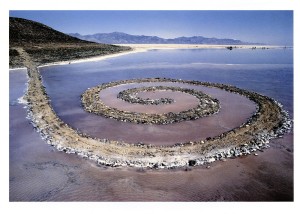

Tacita Dean’s “Salt(A collection)” greeted us with a good sized ball crystallized in potash, a wonderfully physical manifestation of salt, and painted over postcards of the Salt Lake, all referring to her attempt to visit Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty in 1997. The original “Spiral Jetty” film is at the very back of the exhibition marking a primal inspiration for the exhibition as a whole. It partners with an unlabeled video in the Channel of Christov-Bakargiev visiting the site of the Jetty.

As explained long ago by the wonderful art critic John Coplans, Smithson’s sees geology and human thought as aligned. The spiral is relates to entropy and irreversibility, “ a spiral vectors outward and simultaneously shrinks inward – a shape that circuitously defines itself by entwining space without sealing it off.”

The themes of time, entropy, and the return to the earth of what we make are central to Smithson’s thinking,and make it a perfect starting point for the Biennial itself. On the other hand, when I viewed the dinosaur like back hoe creating the jetty in the film, it felt destructive and aggressive. Smithson turned shortly after Jetty to reclamation rather than construction, to working with the land, rather than on it. To working to remediate the destruction of industry. How much we need him today!

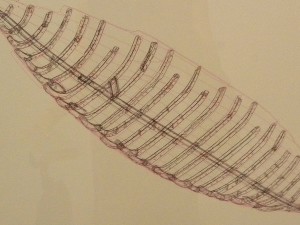

Also at the entrance of the Channel was Emin Özsoy’s scientific photograph of currents in the Sea of Marmara, and beside it

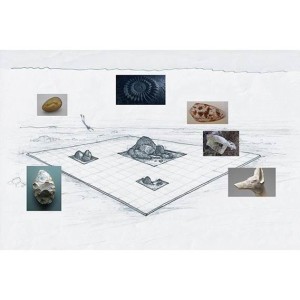

Ufuk Kocabaş’s 3d digital print based on one of the 37 Byzantine shipwrecks found in the bottom of the Bosphorus during excavation for a tunnel. We move on to a book by Darwin “On the various contrivances By which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilized

by insects and on the Good effect of Intercrossing” 1862, an example of the intersections that occur throughout the Biennial.

I am enumerating all of this because it gives a sense of the flow of media, ideas, and connections that materializes the idea of waves and knots in saltwater. The aesthetics of the exhibition forms in our mind as we move from one work to the next.

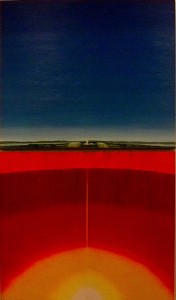

Some of course are more impressive than others, such as Cildo Meireles’ stunning two part painting with 3 cm in between “Project Hole to Throw Dishonest Politicians.” That 3 cm separates the world of bureaucracy and earth’s forces.

This Biennial honored the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide in Turkey in several ways. Michael Rakowitz installation in the former Greek Primary School, a casualty of the declining Greek population in Istanbul. His installation included casts of patterns created by Armenian architects on many buildings in central Istanbul. He used crushed bones to create the casts of the fragments based on still existing molds. The bones came from the dead livestock of an Armenian village, and from dogs from the island of Sivriada where 80,000 dogs were sent to die in 1911 in an effort to modernize Istanbul, the first holocaust of the twentieth century. Cultural artifacts here are architectural pentimenti of tragedy. You can still see these ornamental patterns on many buildings in Central Istanbul.

Rene Gabri and Ayreen Anastas referred to the endangered position of Armenians today: they created a Center for Parrhesia for the Society of the Friends of Parrhesia “one who speaks the truth ” or “free speech” at the foundation created in the offices of the Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, murdered in 2007. Their space is intended for “thinking how to become worthy of what we inherit as ‘history and to what happens to us. “ As a center for free speech, it is, of course, unfortunately dangerous in contemporary Turkey. Erdogan has been jailing journalists, taking over opposition newspapers, and repressing freedom of speech in an escalating campaign to control what is said in Turkey

But aside from the theme of saltwater, waves and knots themselves, the Biennial takes on their metaphors as well such as Resistance as a knot. That is documented by including the Arabic translation of Trotsky’s 1928 text, the Real Situation in Russia, aggressively rebutting Stalinism. It is owned by Christov-Bakargiev. In 1929-33 Trotsky was in exile on the island of Buyukada, without a country. Trotsky’s socialism is important as suggested in Christov-Bakargiev’s comments on the conflict of art that engages issues and the commericialism of the art world. But one might also think of the current situation in Turkey in terms of Stalinist-like repressions by the government.

Perfectly appropriate then that the now- ruined house where he stayed for several years on the Princes Island is a destination for Biennial visitors (along with various installations inside other houses and hotels, as well as a boat, none of which I was able to get to see.)

Camouflaged references to the Gezi uprising of 2013 appeared in various ways if you knew where to look. One room at the Istanbul Biennial included Artiksler Kolektifi’s video documenting the 2010 workers resistance in Ankara.https://bak.ma/

It faced a copy painted by Taner Ceylan of a very large 1901 painting of The Fourth Estate by Giueseppe Pellizz da Volpedo. It is described in the catalog as “a key image for socialist and democratic movements worldwide. A peaceful but energized crowd of protesters in a rural town advances towards the viewer in the morning light of a rising sun. They form a wave and they are full of confidence. They come for their rights. “ An indirect reference to the Gezi uprising?

In the same gallery with the Volpedo and the Artiksler Kolecttifi video was the historical work by Michelangelo Pistoletto Venus of the Rags from 1967, a vivid confrontation of the elite and disenfranchised. Making the Gezi connection explicit, Tunca Subasi and Cagri Saray, in their studio buried deep on the Asian side of the Bosphorus, exhibited a collage of Gezi Park footage created by Ozge Celikasian and Alper Sen (also viewable online at https://bak.ma/.)

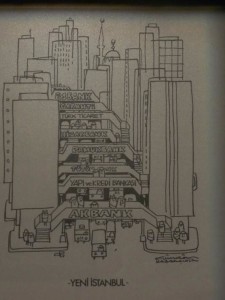

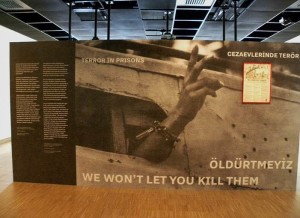

Amplifying the references to public protest , the gallery SALT Beyoğlu in central Istanbul created an archival exhibition “Nerden Geldik Buraya? (How did we get here?)” focusing on 1980s resistance to the military coup, along with protests about unfair imprisonment ( below, “We won’t let them kill you”, urban development “Yeni Istanbul”, the environment and free speech issues of those years. It charted, as the curator stated “the origins of the current context of Turkey at this turning point, in relation to the recent past and via elements of popular culture and social movements that took hold after the coup d’état in 1980.”

One striking newspaper article from the Nation featured a letter by Arthur Miller visiting Turkey stating international support for imprisoned journalists. Would we could have contemporary celebrities calling attention to the many journalists and academics currently detained in Turkey

Arthur Miller article in The Nation “Dinner with the Ambassador” as he visited Turkey to support imprisoned journalists

.

Once we recognize the cloaked resistance we can see resistance and opposition as well as grassroots collaboration in many works in the Biennale. What begins as a ferry ride to appreciate salt water, becomes an intense layered reference to art as resistance to capitalism and the status quo. This Biennial, like the Bosphorus itself, hides itself in layers of references.

Many resonant works contributed to these layers. One of the more disorienting in the Istanbul Modern, Grace Schwindt’s installation Little Birds and a Demon captivated me. A voice precisely narrated the nightmarish condition of birds caught in an oil spill, as we viewed her seemingly unrelated off kilter installation: two irregularly geometric salt “carpets,” a table with one leg on the salt. On it are a copper cauldron filled with what is called “used-pointe-ballet-shoe-soup” and a ladle, soup bowls, a stack of silver spoons, two chairs.

Nothing makes sense, it entirely disrupts our sense of the rational and how to connect it to oiled birds? Their lives are overturned, like the bourgeois setting of the installation? Schwindt caustic comments on the corrosive effects of capitalism: “There is a very limited possibility of freedom in capitalism, because you never reach promise, and that’s my point.” So perhaps lack of predictable action is both for the oiled birds and the residents of the room. The assymetrical salt shapes represent the mining of the earth resources that kills or maims the people living on it.

Near the installation by Scwindt, a roomful of roughly carved stone heads Silence of Stones by Sonia Balassanian. These twelve partially carved heads evoke erasure and suffering, through their unfinished surfaces and somehow through the way they are placed in the space. There is separation between them that seems to prevent any connection. Balassanian again connects to the Armenian genocide, the stone is from Ani, a town in Armenia, but the subtlety of the carving suggests a universal, almost classical angst, like Michelangelo’s late works.

Lebanese artist Marwan Rechmaoui’s 14 ruined towers of concrete “Pillar series” immediately speak of war and destruction: improvised from what appear to be remnants of buildings, the textures and patterns carefully drawn from believable architectural motifs, but at the same time they exist as aesthetic supports created out of desperation, creating a type of concrete garden that recalls the words of Vita Sackville West quoted at the beginning of the exhibition: “Small pleasures must correct great tragedies, therefore of gardens in the midst of war I bold tell.”

Nikita Kadan’s, the Shelter, also called Untitled (Political Natural History Department) makes provocative reference to destruction of museums of natural history during the Ukrainian war. Kadan states “In this period of Ukrainian life, the position of a citizen, a normal citizen, and the position of an activist have become very close . . . To be a conscious citizen means to be a social-political activist now.” His two part work features (seemingly disoriented) artificial deer who have emerged from their dioramas into the street, behind them are the rubber tires used as barricades in Kiev, and below, cases growing celery in the dark, suggesting subsistence survival.

Speaking of surviving social structures, the installation by Senam Okudzeto Glossolalia no 12, part of an ongoing project called “Portes Oranges,” celebrates women’s economy, particularly through the sale of oranges, and the sculptural displays created in Ghana.

Also addressing positive outcomes was the amazing group of Australian aboriginal paintings that demonstrated ownership of the land and sea.

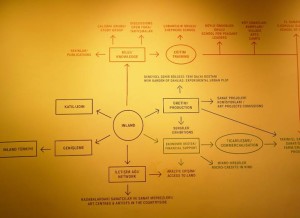

In another venue an installation by Inland diagrams their connections to artists, farmers, intellectuals,rural development agents, policymakers, curators and art critics,amongst others. In Istanbul, it joined with rural groups in Turkey Alternatif Uretim near Diyabakir and Ularca (Soma).

Theaster Gates “Three or Four Shades of Blue” inspired by Iznik pottery was a “store” where he created bowls made of dust taken from resonant sites in the city. Gates interacted with the public , you can just see him sitting on the floor in the background.

(upstairs were videos of jazz singers).

At the end of my trip, I had the opportunity to travel up the Bosphorus to the Black Sea, although my experience was quite different from the intended relaxing ferry rides on salt water. From the land I saw the devastation of acres of precious forests caused by the construction of the controversial Third Bridge, new airport, and superhighways, even including the boom of a dynamite blast that sent a cloud of smoke into the air.

I saw families who had braved hours of traffic jams to enjoy a very hot afternoon wading in the Black Sea, and

I experienced the high rises of contemporary Istanbul. This is the reality of Istanbul today, a long way from the languorous ferry rides and borderless utopian world imagined by the Biennial.

Perhaps for that reason my favorite work was a video by Pelin Tan and Anton Vidolke A science fiction fantasy Episode 2 The Fall of the Artists Republic. In the intentional contradictions that filled the Biennale, it was shown in a cistern under a boutique hotel in the center of old Istanbul.

The video itself was filmed in an abandoned dome building in Beirut that is part of the former Rashid Karami International Fair Complex designed by Oscar Niemeyer from 1962 – 1974.Five people with dog, chicken and horse masks, as well as a human, recited the story of the Fall of the Artists Republic. It recounts a great people’s uprising that led to remaking the world; they made “art so beautiful that people became animals.” Feeling became the economic resource, but the great utopian experiment failed, leaving only these few creatures inside an abandoned utopian structure.

The Biennial’s originality, complexity, and refusal to settle for predictability, made it one of the best international exhibitions I have seen in many years.

This entry was posted on October 15, 2015 and is filed under Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul Biennial 14, Turkish Women Artists, Uncategorized.

QUIET INSIGHTS INTO STRUGGLE AND JOY AWAIT YOU AT THE WING

A tall canvas house looms over us in the first room of “Constructs: Installations by Asian Pacific American Women.”

Lynne Yamamoto’s Whither House honors Japanese-American farmers who could never put down roots. With no windows and doors, the house stands insecurely on log rollers. Up until 1952 “alien land laws” targeted Japanese farmers, preventing them from owning or even leasing land if they were not eligible for citizenship. Many lived in tent houses, tilled land, made it productive and then were forced to move on. And of course, after Pearl Harbor, in the spring of 1942, they were sent to internment camps, where they made even that inhospitable land productive. This simple white tent house that feels so large in the gallery, speaks to that history.

Kaili Chun, Janus, detail, 2010. Steel cells, locks and keys, MP3s, audio speakers. Photo by Toryan Dixon Courtesy of The Wing Luke Museum

We pass into a narrow gallery, on its walls a row of small double locked cages containing a speaker. Kaili Chun‘s installation, Janus, requires us to open the door and to listen. As an Indigenous Hawaiian, Chun deeply feels cultural colonization, both in history and in contemporary agriculture and tourism.

Decontextualized indigenous artifacts from her past survive mainly in museum display cases. As we juggle the two keys and unlock the cage, we listen to the fragments of sounds (or silence), experiencing the disruptions of a trapped culture: waves or birds, or wind, or rain or people singing childlike songs. Some are silent. We feel the oppression as we relock the cages.

Yong Soon Min’s installation LIGHT/AS/IF subtly evokes the elusiveness of memory directly connected to the artist’s own traumatic loss of language and memory from a cerebral hemorrhage. On a wood plank, the artist carved tiny braille letters, quoting from Rumi “The Wound is the Place where the light enters you.” Then, in the artist’s own words, “Invisible wounds are the hardest to heal. They throb with buried memories, telling me that the past is real and that I’ve survived. Of the visible scars, some are unbelievably seductive, as if turning a blind eye to the pain that was the source.”

Braille, which the artist does not read, refers to the way she feels. Loss of sight, like loss of memory, alters our perception of our place in the world, present and past, a frighteningly disorienting experience. Nearby, another wooden plank holds a porcelain bowl of water. As the water slowly evaporates, it marks the passage of time, a metaphor for the slow extended time required for healing. A third piece, a wooden “tree wound” carved by a digital router, also echoes Min’s situation, one step removed from the creation of the work, one step removed from her former reality. A huge ball with texts referring to loss/wounds/healing rolls around in the midst of these subtle pieces, an uncontrolled game with unknown rules, much as life can be for those who lose their memory and the ability to speak.

After Min’s meditative work, Tamiko Thiel and Midori Kono Thiel, mother and daughter artists offer us exhilaration and adventure. Midori Kono Thiel’s Japanese calligraphy becomes abstract art as she writes each stroke of a character on overlapping transparent sheets. Tamiko Thiel, with two engineering degrees, superimposes the calligraphy on an actual place viewed through a tablet or smart phone. In addition to the museum installation, Brush the Sky floats words written in Japanese calligraphy at seventeen locations in Seattle. We can go, for example, to Pike Place Market, the Panama Hotel, the Japanese Garden or the International Fountain, hold up the tablet and read a Japanese phrase that pertains to the site. Each site has personal significance for the artists. At the International Fountain, for example, the calligraphy reads “ Astonishment/Past Present Future.” Their friends Kazuyuki Matsushita and Hideki Shimizu designed the fountain as homage to our efforts to explore outer space at the time of the Seattle World’s Fair. The words float over the site, and “augment it” as we see it on the tablet. A brochure in the gallery includes the Japanese and the translation of each site along with the bar codes.

Terry Acebo Davis, In Her House … Tahanan … Her Room, detail 2015, Bamboo, tyvek, family photographs, wallpaper, found objects, mirrors, bronze, bedroom furniture, banigs (traditional woven mats) Photo by Toryan Dixon Courtesy of The Wing Luke Museum

Almost unbearably intimate, Terry Acebo Davis’s In Her House…Tahanan . . .Her Room honors her mother, as well as the experience of dementia. She asks us to take off our shoes and sit on the bed beside a pink bathrobe and a telephone receiver, suggesting an incomplete connection. A large photograph of her mother as a beautiful young woman hangs above the bed with family photographs on a nightstand nearby. A reversed clock suggests her dementia. As in Yong Soon’s work, we are looking at fragments, references to missing pieces, the sense of the coming apart or the inability to put together, the real. In its place are mementos, photographs, scraps of writing.

Each of these installations invites us to participate: we walk around the house and smell its wood, we open steel cages, we touch the wood carved braille, we wander in the midst of the calligraphy and bring it to public sites, and finally we sit on the bed of an aging mother. We can explore and feel emotions we rarely have the opportunity to experience in an art museum in this subtle exhibition of interactive installations.

While you are in the Museum, you can also visit the “Bojagi: Unwrapping Korean American Identities,” in the downstairs gallery. “Bojagi” is a cloth made “Bojagi” is a cloth made of many pieces. It provides the metaphor for a multimedia and multisensory exhibition, with references to visual art, music, theater, dance, writing, education, and much more.

Finally in the corridor outside, several panels address immigration and deportation, the physical part of the exhibition “Belonging: Before and After the Immigration Act of 1965,” expanded online with a community digital exhibition with visual art and poetry. You can see that without leaving your home.

What you are shortly going to hear about from the Wing is the Bruce Lee exhibition, opening October 4. But before that razzle-dazzle, spend a quiet hour with “Constructs” (which is up until April 17, but don’t wait )and then visit “Bojagi” which closes on November 15.

THE WING LUKE MUSEUM OF THE ASIAN PACIFIC EXPERIENCE

719 S. King St, Tues to Sun, 10am-5pm, (1st Thurs until 8)

This entry was posted on September 24, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Feminism, Uncategorized.

I GRIEVE FOR SYRIA, VICTIM OF CULTURAL GENOCIDE

Guest Post by Henry C. Matthews

When I traveled in Syria in the spring of 2006, I found a hospitable people with hopes for the future that appeared plausible. Although people I met there deplored and feared the Assad regime they expressed optimism that the situation would improve. Lacking economic resources, the nation was poor, but, having achieved a high standard of education, it was rich in human capital.

Today I feel intense grief for the Syrians, their culture, their ruined cities and their lost architectural heritage.

Syrian Refugees blocked from boarding trains at Budapest Station

Syrian refugees in Jordan

The horror of the current Syrian refugee crisis, coinciding with the destruction of the two thousand year old Temple of Bel at Palmyra, intensified the pain that I have felt ever since Bashar al-Assad ordered police to attack peaceful protesters with live bullets in the spring of 2011.

Victims of police murder ordered by Bashar al Assad, spring 2011

The Temple of Bel, Palmyra (32 CE)

Tower Tomb of Ehlahbel (103 CE)

I saw these temples in 2006. they were destroyed by ISIL August 30 and September 2 2015

When I made my plan to visit this country, I was drawn, as an architectural historian, to archaeological sites from Ugarit which produced the world’s first alphabet in the fourteenth century BCE to the imposing Roman city of Palmyra, the significant Early Christian churches, the great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus and crusader castles.

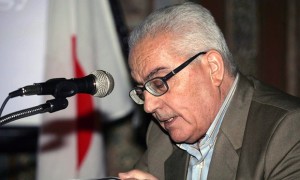

Bassam Kahaleh, translating my lecture at the University of Damascus

Damascus

But, wanting to meet contemporary Syrians, I contacted Bassam Kahaleh who had been my teaching assistant at Washington State University many years earlier. Running a leading architectural practice, he had become the president of the Syrian Order of Architects. He invited me to lecture both at the University of Damascus and at the Professional Society. This opportunity enabled me to engage with faculty and students.

When I look at the faces of my audience at the university or the group of students who joined me for conversation afterwards, I agonize over their present situation. How many of them are still alive? Are they scattered through refugee camps, attempting to flee to Europe, or still in Damascus?

Although Bassam translated my lecture, many of the students asked questions in excellent English. One of them told me that their passion for contemporary architecture forced them to learn English so that they could study books unavailable in Arabic. I found the faculty progressive, and articulate. Women outnumbered the male students in the school of architecture.

Bassam showed me around Damascus, invited me to his office and to his home, where I met his delightful family and enjoyed a memorable lunch. I hope that he and his family are safe.

Hama

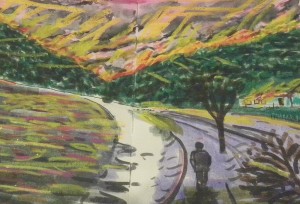

The water wheel at Hama, Syria painted by Sameer Tenpor

Traveling through Syria with a small group I saw many inspiring sites. At Hama, I marveled at several ancient water wheels, known as norias, successors to devices that have raised water for irrigation from the Orontes River since the Byzantine era. I visited the nearby studio of an artist Sameer Tenpor, talked with him for a while and bought the watercolor shown here. He used coffee as his pigment. Of course, every time I look at this painting, I wonder what has happened to him.

In Hama, protestors suffered the consequences of courageously sticking to their principles. The water wheels survive today, but many citizens died or suffered serious bullet wounds.

Aleppo

In Aleppo I had the honor to meet with the architect Adli Qudsi at a significant moment in his career. The next day Aleppo was to celebrate its designation as the Islamic City of Culture for 2006, a tribute to his years of work as leader of conservation efforts in the old City. In 1975, distressed by deterioration of the area surrounding the al-Madina Souq and appalled by a master plan that threatened to drive straight roads through the historic area, he appealed to the government in Damascus to apply for World Heritage status for the city. Thanks to his efforts over many years, this was granted in 1998. When I visited his office, he told me of his strategies for preserving the historic core. It seemed, then, that with funding from the Aga Khan foundation, his well-conceived proposals would be implemented: historic Aleppo appeared to have a future.

Aleppo Citadel 12th -14th centuries CE and Adli’s niece, the director of restoration

The next day Adli’s niece who was directing restoration at the citadel took me on a tour of it. In this formidable urban fortress, dating from the 13th century I witnessed large scale reconstruction work. She showed me lavishly ornamented residential spaces and a beautiful hamam, as well as the fortifications.

In recent years ,the Syrian government has revived military use of the Citadel and used it to bombard rebel held areas of the city. Since no observers have been allowed to enter, the condition of the interior remains unknown. But on July 12 2015, a bomb in a tunnel beneath the fortifications exploded , bringing down a long stretch of the walls.

Bomb Damage to the Citadel

Fighting in Aleppo resulted in the destruction by fire of the Al-Madina Souq, one of the largest covered markets in the Islamic world, essential to the life of the community. This loss robbed thousands of people of their livelihoods and their heritage

The Al-Madina Souq, Aleppo 2006. Now destroyed.

I cannot even imagine the anger and disappointment and heartbreak that Adli Qudsi and his niece must feel. Not only are the physical buildings in ruins, cultural places in which generations of people lived, worked and conducted business are lost forever.

Early Christian Churches

Church of St Simeon Stylitis

I was particularly excited to see the architecturally ambitious Early Christian church of St Simeon Stylitis (c.470), a cross shaped martyrium with four long arms, each one like an individual basilica, meeting at a vast octagonal crossing. Only the walls stand, but the architectural detail survives to animate the ancient structure in an inspiring way.

I was relieved to read, today, that although this church was at one time captured by rebels, who might have destroyed it, the site was subsequently liberated from them undamaged. However, the 5th century church of Saint Sergius at Raqqa, near the River Euphrates has been completely demolished by ISIL. When I stood within these arcades with their subtle rhythm and exuberant capitals, I felt a deep connection with the people who built it a millennium and a half before. Now it is nothing but dust and rubble.

Early Christian Church of St Sergius Raqqa. (c.570 CE)

Palmyra

The pomp and splendor of Roman architecture has never appealed to me, but, since Palmyra stood out as a superb example of the Roman imperial city, I was eager to see it. Today we do not worship the fire god Bel for whom the destroyed Temple of Bel was built, nor do we revere the Emperor Trajan in whose reign it was erected. But this architecture offered powerful evidence of history.

Dr. Khaled Al Assad

On August 18 2015, in the Roman theater, child soldiers under the command of ISIL, executed Dr. Khaled Al-Asaad who had been the director of antiquities at Palmyra since 1963. His ‘crime’ was refusing to divulge where archaeological treasures were hidden. They beheaded him and hung him upside down from a column. This unspeakable murder and the destruction of Syria’s architectural heritage rank as heinous war crimes.

The theater at Palmyra where Dr, Al-Asaad died

Armenian Genocide Memorial Deir Ez-Zor

Exhibit of an atrocity at the Armenian Genocide Memorial, Deir Ez-Zor

The church and Museum destroyed by ISIL in 2014

An unforgettably poignant experience on my journey to Syria was a visit to the church and memorial to the Armenian Genocide at Deir-Ez-Zor. Having made a pilgrimage seven years earlier to the tenth century Armenian church of Aght ’Amar on an island near Van in Eastern Turkey and learned what I could about the genocide, this visit in Syria meant a lot to me. I was horrified to discover recently that this symbol created by survivors of the genocide and their descendants had fallen prey to ISIL. As if the Armenian community had not suffered enough already, they dynamited it on December 21 2014.

Supported by weapons supplied by Vladimir Putin and other outside forces, the Assad Regime may hang on to power even after further death and destruction. But Syria, as millions of Syrians knew it, and I experienced it briefly, is lost forever. Much of the surviving, well-educated middle class has already left the country. Some of the great architecture that attracted thousands of tourists and contributed to a rich national identity has been obliterated.

ISIL, which emerged in a Middle East destabilized by the disastrous Iraq war, tragically continues to wreak destruction and perpetrate its ignorant version of religious oppression.

I grieve for Syria, for her people, her culture and her architecture.

On September 8, Annette Groth, member of the German Parliament and spokeswoman for human rights for the Left Party. talked to Amy Goodman on Democracy Now .She just returned last week from a trip to Hungary, where she saw thousands of migrants stranded at the Budapest train station. “What is the root for this massive migration?” Groth asks. “It is war, it is terror, and it is the former U.S. government who is accountable for it.”

School Children in Damascus

School children outside the Museum in Damascus. Where are they now?

This entry was posted on September 16, 2015 and is filed under Syria, Uncategorized.

After Midnight: Contemporary Art in India At the Queens Museum of Art

Pioneering Mumbai gallerist and curator Dr Arshiya Lokhandwala rejects predictable clichés about art from India in ‘After Midnight: Indian Modernism to Contemporary India 1947/1997’ at the Queens Museum of Art. The title, refers, of course, to Salmon Rushdie’s novel Midnight’s Children, about the nightmare of the Partition of India and Pakistan. In this exhibition, though, the primary theme is dialogue, the dialogue among artists in India and between those artists and global art, during two eras, that of the ‘Progressive Artists Group’ who emerged after Independence in 1947, and that of a generation who emerged 50 years later in the midst of globalization.

The two generations overlap, of course: many of the older artists lived into the 21st century. The project of this exhibition is to demonstrate that continuity and conversations with global art is a continuing project in India.

The first generation of modernist artists reacted against the nationalist traditions in India created primarily by the Tagore family in the context of the Indian Independence movement. They embraced international modernism. The first gallery of ‘After Midnight’ presents some of these works by artists such as V.S. Gaitonde (recently the subject of a stunning retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim), Tyeb Mehta, Akbar Padamsee and F.N. Souza. The works came mainly from private collections in New York, resulting in only token representation of these major artists.

Experimental films, photographs and archival catalogs enriched the presentation of the ‘Progressive Artists Group’. Several of these artists worked in New York City in the late 1960s on Rockefeller fellowships.

From this era are three films, a completely abstract work by Adbar Padamsee, Syzgy from 1969–70, a film in which the artist animates his abstract drawings. In stark contrast, Tyeb Mehta’s film Koodal immerses itself in physicality, the killing of a cow in a slaughterhouse along with mobs of people in the streets of Bombay. Finally M.F. Husain’s film Through the eyes of a painter presents the physical reality of India, but as an aesthetic concert of images that embrace visual contrasts of the land articulated by a soundtrack of Indian music.

These three films present the first stage of avant-garde filmmaking in India. All three pursue distinctly different approaches from the realism of modernist cinema giant Satyajit Ray, for there is no story, no actors, no dialogue, only imagery. The archival materials document the artists’ active professional life in India, notably with the gallery Chemould Prescott Road, which still supports avant-garde art in India.

The second half of the exhibition expanded unpredictably almost like a treasure hunt: a few works occupied three traditional gallery spaces, then the show sprawled out across vast walls in a central atrium, erupted under a staircase, with a work by Asim Waqif using recycled packing cases, then moved to the observation walkway for the 1964 Panorama of the City of New York. It concluded in three more traditional gallery spaces. The contrasting spaces disrupted the usual continuity of one square gallery after another and likewise our thinking. It reminded me of being in India, where scale shifts drastically from, for example, the human scale markets in Old Delhi to the overwhelming scale of Edwin Luytens’ late colonial city scape.

In one small gallery, a two-screen video, Strikes at Time, by the Raqs Media paired the interior of a bus with mythical guardians on one screen, and night-time views of a worker going to his job on the other. We experience the ordinariness of the worker’s life, unpredictably animated by the magical and the supernatural.

Destuffing Matrix, a video by CAMP, addresses globalization. In four simultaneous projections of loading and unloading global products, interspersed with documents, bills, and lists of contents, it tells the story of global commerce, of consumerism, of perpetual movement of goods. Sharmila Samant’s Mrigajaal – The Mirage focuses on the local in a single channel: a water diviner locates water, and exposes unequal water distribution between rich and poor neighborhoods in Mumbai.

Subodh Gupta

Continuing the theme of boats and water, a traditional South Indian fishing boat filled with pots and pans, as well as bundled possessions, suggests a life in transition in Subodh Gupta’s What does the vessel contain that the river does not? The title invokes a poem by Persian Sufi mystic Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī that suggests that the universe is contained in a single soul. Placing the boat in a gallery monumentalizes the ordinary and suggests the universality of everyday experience. It enshrines a way of life that is disappearing.

Jitish Kallat

Also in the atrium is Jitish Kallat’s Public Notice 2003, recording the inspired words of Nehru’s ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech delivered just before independence. But the stencilled letters of the words of the entire speech, written in glue and then burned on rippling mirror panels, evoke both the hopes of that moment, and their ruins, as Independence led to so much violence. They are barely readable.

Placing videos of the urban performances by Nikhil Chopra on the walkway above the New York City Panorama created an inspired intersection. As we watch Chopra as Yog Raj Chitraker in New York City or on a 15-mile traverse of Mumbai, during which he changes his clothes from impoverished to aristocratic according to his surroundings, we understand that the urban experience is that of observation of the other.

Sheela Gowda

‘After Midnight’ was framed by two major sculptures/installations. In the entrance lobby Sheela Gowda built Blanket and the Sky from tar drum sheets. The metal sheets get flattened for road paving in India, then are recycled as the material of temporary shelters. As we thrust our heads into the opening in Gowda’s columnar structure, we see cut-out square huts and cavities of the same metal, a squatters’ village. We are giants looking at the small people, the centre looking at the periphery, the oppressor looking at the oppressed. The darkness inside is lit only with pinpricks of light.

At the end of the exhibition, Atul Dodiya’s Three Brothers consists of three empty wooden cabinets, painted with squares of color that suggest Suprematist abstraction, each with a photograph: a victim from the Nazi holocaust, a person in the agony of the Partition, and a ghostly, faceless worker, a representation of a late painting by Malevich at the tragic time when Stalin was cracking down on the avant-garde in the Soviet Union at the end of the 1920s. Above the cabinets are framed photographs of skeletons – humans, dinosaurs and animals – in museum cases (the ‘skeleton in the closet’).

Dodiya frequently comments on the process of museum viewing in his work, but rarely so specifically. In Three Brothers, he emphasizes that museums freeze horrific catastrophe as relics.

A photograph,, on the back of Three Brothers, shows a businessman plummeting to his death on 11 September 2001, silhouetted against the modernist stripes of the tower. The destruction of the World Trade Center has led to thousands of deaths not only at the time, but also continuing to the present in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East. Dodiya here equates it to the Holocaust, the Partition and the death of the avant-garde in the Soviet Union. He expertly layers politics, metaphor, and formalism.

‘After Midnight: Indian Modernism to Contemporary India 1947/1997’ presents the reality of the sophisticated dialogue of contemporary Indian artists with global ideas of modernism, postmodernism and contemporary issues from the late 20th century to the present.

This entry was posted on August 28, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.

Joy in Greece in the midst of Crisis: Constellation

I am happy to present a Guest Blog by Henry C. Matthews

As the economy of Greece collapses and the people suffer serious deprivation, counter cultures are taking action. Barter systems and volunteers offering essential services satisfy some practical needs, but creative young people are also attempting to fill a cultural void. One endeavor on a remote Cycladic island celebrated its third year from 17-28 June 2015. Constellation of Amorgos, offered free entertainment every evening in a variety of inspiring milieus.

Here is the dynamic team of organizers

While donors have provided ferry tickets and accommodation for the performers, the artists, some of them internationally renowned, have donated their own time and talent.

The festival opened with traditional music in a quai-side café at the harbour of Aegiali, After processing to the “Skopelitis” a small inter-island ferry, the musicians played all the way to the port of Katapola at the other end of the island.

A party developed on board with dancing and libations of psimeni raki by the light of the setting sun. The festivities continued until 11:00PM that night at a cafeneion, when a bus transported participants back to Aegiali.

Other events included a dance performance by Anna Lianopoulou in an ancient cistern in the village of Potamos; a poetry reading by Elena Mpei and George Antzoulakos in a chapel at Katapola; acrobatics on the beach at Aegiali; story telling by Sofia Papanikandrou about “the Myths of the Stars” in a village south of Katapola and a performance of eighteenth century music on lutes and mandolins by “Plectrum Lab”.

They gave this peaceful concert at Drys, a beautiful spot in in a gorge below the mountain village of Langada where, for generations, the inhabitants fetched spring water. As one might expect, on a Greek island, the twelve days of performance ended with feasting, music and dancing from noon until late at night.

A highlight of the festival occurred beside a tiny church by a ruined Hellenistic tower at Richti, down a steep path from the road leading from Aegiali to Chora, the main town of the island. For spectators crowded onto steep steps above them, the internationally known “l’Anima String Quartet” played recent works by six contemporary Greek composers: Dimitris Sikias (String Quartet 2 / Fomalhaut – the mouth of the Southern Fish), Lina Tonia (Mnemonion), Fani Kosona (Views, 7 small pieces for string quartet), Apostolos Paraskevas (Aegean Fire),

Thodoros Antoniou (String quartet no4), and Panos Liaropoulos.

Panos Liaropoulos, introduced each piece to the audience in English. His contribution, entitled “Lament”, composed specially for this concert, showed that avant garde music could resonate, as well in this wild landscape as in the concert halls of Europe and the USA. This inspiring concert was dedicated to the memory of Iannis Xenakis, the famous composer and architect.

This festival is a fabulous example of the Greek spirit of creativity in the arts that dates back thousands of years. It survives today, in the midst of all of the stresses of Greece.

The website www.amorgosfestival.gr give more details and offers a chance to donate. So if your heart bleeds for Greece, a land of music, dance, art and wine, you can help future festivals to flourish.

This entry was posted on July 7, 2015 and is filed under Greek Festival, Uncategorized.

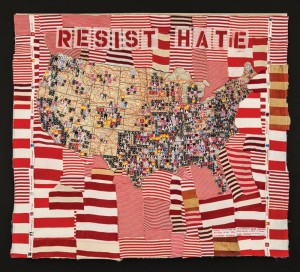

“Migration” the exhibition until July 5

Where does one begin to talk about migration to the US from the Global South? Do we begin with the racism embedded in the Constitution at the founding of the United States that designated only property-owning white men as citizens? Do we begin with the history of US intervention in Latin America, our innumerable coups from 1798 to this day that over throw any government that we consider antithetical to our economic interests or which even considered enacting programs to help ordinary people? Do we begin with Free Trade Agreements that are bankrupting the small farmers of Central America and Mexico? Do we begin with the Drug Wars, the mafia, the violence, also fueled by US dollars? Do we begin with the detention system first set up to target the families of Chinese railroad workers in the 1880s? Or perhaps with the Immigration Act of 1965 which extended regulation to the Western Hemisphere? Suddenly migrant laborers without papers were counted as illegal aliens. I hope to create a book that will include art about all of these issues.

For this blog post, I will focus on the many issues raised by three artists, a poet and a community activist, in the exhibition “Migration” in the Columbia City Gallery Seattle this June.

Let us begin with Tatiana Garmendia‘s video work “New Colossus” which alters the original message of the poem inscribed near the Statue of Liberty. As we watch her sorting coffee beans more and more rapidly (an activity she was forced to do while in detention in Cuba as a child), she repeats some of the famous words of the poem “The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus:

“Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

But as the beans are sorted faster and faster into four piles, white, and shades of brown, the Lazarus poem is increasingly overwhelmed by another set of statements:

“Send me your well to do,

your educated,

your engineers,

your doctors,

your Europeans,

your light skinned,

your well fed,

your rich with many homes,

your refugees with money

your middle class with suitcases full of loot . . .

Lazarus wrote her poem in deep sympathy with Jewish immigrants pouring into this country as a result of pogroms in Russia. As it is altered in Garmendia’s “New Colossus,” it reflects our vastly changed economic and social migrations of the early 21st century. The reference is also personal, for she remembers her mother crying as she read the original poem as they entered the US for the first time.

This video is part of a series that the artist calls “The Triumphs.” For the first time, Tatiana Garmendia confronts her own childhood experience of detention and immigration. Born in Havana, Cuba in 1961 to a family of active supporters of socialism, they greeted Castro with delight. As a doctor, Tatiana’s father joined the army and worked in rural communities. But, not long after, political conditions became convoluted and he fell into disfavor. Tatiana’s family went into a detention camp in 1966 where they remained for almost three years.

As a young child, Tatiana witnessed atrocities and rape while in the detention camp. Her father was tortured and disabled. They finally reached the US in the fall of 1969.

In this exhibition Tatiana honors her father with a photograph of a blanket sewn with words that describe the methods used to torture him. It is a document of a ritual that she performed over many months.

For the artist, it was profoundly traumatic to be confronted with the reality that the US uses these same techniques at Guantánamo, and in other detention sites all over the world. The public exposure of that fact has made the depth of our hypocrisy on human rights unavoidable.

Tatiana has only now been able to begin to explore these painful memories. She draws on references to the Tarot and Santeria as a way to access her feelings. Santeria is a syncretic religion that grew from the slave trade in Cuba. It is also known as La Regla Lucumi and the rule of Osha.

Two works explore the contradiction of Castro’s charisma and the realities she experienced as a child in detention. In Fuse, we see a fusion of her own face with that of Castro’s expressing various emotions. The concept is that Castro’s mystique can actually inhabit her spirit, and those of others around the world.

In a second piece exploring Castro’s charisma, Mi Fidel, the artist takes on Castro’s mannerisms and turn of phrase; in the background are photographs of young soldiers, audiences, a soviet missile, flimsy boats of refugees trying to escape, and protest marches.

These two pieces embody the painful contradictions of multiple realities. On the one hand the charismatic leader, on the other, the suffering of many Cubans. It is believed in Cuba that Castro has a magical protector, a spiritual guardian that protects him, rides other spirits, and takes possession of them. The artist feels this as she takes on his identity, even as she knows “ in her body” as she dramatically stated, that he created great pain and suffering.

In La Patria Querida, My Dear Homeland, the artist dances with a skeleton, invoking a childhood memory of a youth who entertained herself and other children in the detention camp with a performance for which he was later tortured.

She refers to human trafficking using her own body in Border Crossing. The artist lies almost naked face up, with eyes staring, as we hear a partially coherent series of phrases “the mouth of the border has nothing to say; my border is a mouth; you crossed with nothing to say; why did you cross my home,” and many more variations on these words. These are hallucinations of a desperate woman who is either in a trance like near death state or already dead.

The motionless body is spotlighted from above, as though a surveillance airplane has found her, and at the end of the haunting soundtrack by the band Rachel’s ironically titled “wouldn’t live anywhere but here” there is the sound of a helicopter. Eerily, we realize that the woman is indeed dead in the desert, trying to cross the border, the passport stamps on her body implying it is legally entering, but she has reached the dead end of the last border crossing.

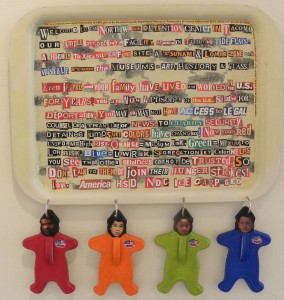

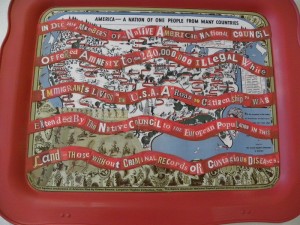

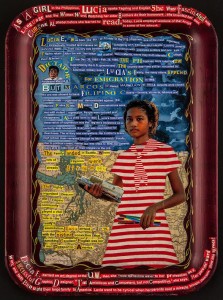

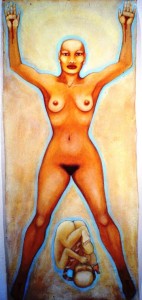

Cecilia Alvarez also addresses violence against women at the border in her larger than life painting of a nude woman, with stigmata, “Los Eternos Sacrificios, Eternal Sacrifices.”