@Large Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz

@Large Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz honors people who are detained around the world for political reasons. In some cases, many of us do not even know about these struggles.

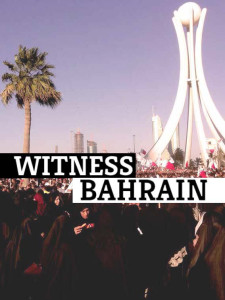

For example, Bahrain, which rose up against oppression in 2011, and continues to do so, is not on the world media radar. But fifteen brave activists from that country are included in Ai Weiwei’s homage. Recently, an outstanding documentary film by Jen Marlowe about Bahrain’s ongoing resistence to oppression has been released called Witness Bahrain.

Ai Weiwei was detained for almost three months in 2011, ostensibly for tax evasion, followed by house arrest, and he is still under surveillance and can’t leave the country. He has though, been able to continue to create work all over the world in absentia. In one venue at the Venice Biennale in 2013 he installed a group of six boxes each five feet high, the measurements of his cell, and recreated inside of them the repressive experience of detention which invades every aspect of daily life. Reading Orange is the New Black by Piper Kerman gave me insights into that dehumanizing process survived only by the strength of the human spirit. Mahamedou Ould Slahi, still in detention in Guantanamo, details the torture he survived in the incredible Guantanamo Diary Another recent publication that describes both revolution and detention as well as torture is Diaries of an Unfinished Revolution, Voices from Tunis to Damascus.

As we approach Alcatraz Island on the ferry, full of tourists who have no idea of the installation, we see its present and its past. You first see “Indians Welcome” behind the sign for the penitentiary from the 1969 – 71 occupation led by Mohawk activists.

A surveillance tower still stands, but most of the buildings themselves, are now in ruins. They were occupied by the families of the guards before the prison closed in 1963 and it was creepy to read about their dances and social events.

As we enter the first massive space, we are immediately confronted by a dragon, his mouth wide open, his long teeth threatening. Symbol of imperial power, this dragon expresses both rage and futility. Made of dozens of kites hand painted in China, it lunges at us, suspended from the ceiling, its body weaving back and forth through the columns of the enormous space. But it is trapped. It cannot move.

The space, the “New Industries Building” served as a vast laundry room where inmates manufactured army uniforms under close guard and for a pittance (their work organized by a company that still continues to do this in US prisons to this day).

@ Large was created under the sponsorship of the FOR-SITE Foundation led by Cheryl Haines in collaboration with the National Park Service and the Golden Gate Conservancy. She thought of the idea of an installation on Alcatraz, then happened to meet Ai Weiwei in China, just after his release in 2011. Ai Weiwei wanted to broadcast injustice inside and outside China: it was a perfect fit. But it took a lot of diplomacy to gain support: it is the first time any art event has been held at Alcatraz.

Near the dragon are “bird kites” that reference countries holding political prisoners. These threatening, unmovable birds emphasize the contradiction of their “detention” with the freedom of the many birds on Alcatraz Island, now designated as a bird sanctuary.

Ironically, the kites are titled “With Wind,” suggesting what would happen if they were able to fly, and underscoring its absence.

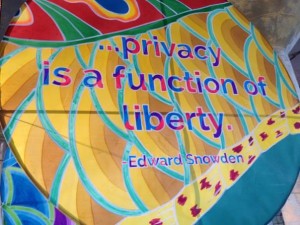

Some of the kites that form the dragon have quotes from human rights activists who are included in “Trace,” installed in the second vast room of this former industrial factory.

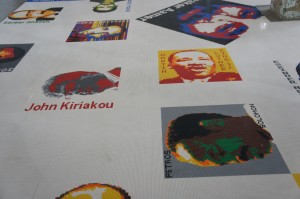

From looking up at kites, we look down to the floor at portraits of 176 people imprisoned for political beliefs in 33 countries. The portraits are constructed in small Legos, with various sizes and colors, meticulously composed by means of grids. They are arranged in a pattern set in a white (Lego) ground; we can see them as individuals, linked by a common grid of restraint.

Ai Weiwei figured it all out from China. He is also an architect, so he was able to work with models and dimensions. He understood and experienced the confinement of his detention cell (another work seen in Venice and in a travelling retrospective recreated the exact dimensions of his detention cell). His work has frequently addressed our relationship to architectural spaces and its components.

Before I went I was dubious about the use of Lego, but actually, the digitized portraits perfectly express the barely visible condition of most of these prisoners. Volunteers in San Francisco matched the legos to templates, a demanding and complex process. Five large segments were put together over three weeks by 90 volunteers following patterns (does it echo the virtual slave labor that took place in this building?).

A few of these portraits honor past heroes like Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King. At the very front are Edward Snowden and John Kiriakou.

The 38 Chinese prisoners form a single huge segment on the floor, the only group that was assembled in China. As we move through the vast room we look at faces and names.

(We can’t walk on the Legos, so we see them from an angle, again appropriate for these disappeared detainees). In a book on a pedestal, as well as online we can read each of their stories.

The artist worked in collaboration with Amnesty International to select the names to include, and of course these are only a fraction of who might have been included.

For example, for the United States, there are only six names. Where is Mumia Abu Jamail? Why only one prisoner from Guantanamo, Shaker Aamer. I expected to see Mahamedou Ould Slahi. There are in fact still 122 prisoners at Guantanamo, 56 of whom have already been cleared for release. Those prisoners, like many of the political prisoners in @Large are all victims of a profound violation of human rights and falsely accused of actions which they did not commit.

We view a third installation in the same immense building, “Refraction” from a narrow passageway looking down through broken windows. Originally, armed guards stood here watching prisoners work; we take their position. “Refraction” suggests the wing of a huge downed bird. Made from giant solar panels used in Tibet as solar cookers, it again represents immobility. On top of some of the panels are teapots or small pans referring to their original use, as well as perhaps the human spirit rising above adversity.

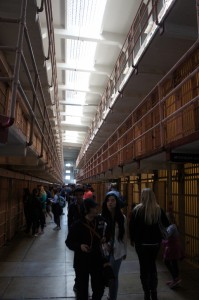

From the New Industries building, we descended down the hill to Cellblock A, part of the public tour of Alcatraz. Ai Weiwei had to argue to get permission to use it.

Inside these old fashioned and crumbling cells built before Alcatraz was a federal prison, we sit on a small stool in each of twelve cells and listen to “Stay Tuned,” songs, poetry and speeches by people or groups, imprisoned for their creative expressions. They speak in their native languages. Outside the cell is an English translation. It includes familiar names such as Fela, Pussy Riot, and Martin Luther King, obviously making the statement accessible to the general public who have no idea that @Large exists, and have come simply for the standard Alcatraz tour. It is a haunting emotional experience.

Even more penetrating are two sound installations, “Illumination”, in the psychiatric isolation units of the adjacent prison hospital. Buddhist monks and Hopi Indians (who were imprisoned at Alcatraz for refusing to send their children to government boarding schools) chant, separately, in windowless spaces.

In the rest of the hospital, another installation, “Blossom,” consists of hundreds of white porcelain flowers which fill derelict sinks, toilets and bathtubs almost to over flowing. As one of the art guides said, “Porcelain is strong, but fragile, like free speech”. Putting them into plumbing fixtures suggests they could be flushed away at any time. The flowers also reference the artist’s father’s own experience in the 100 Flowers Campaign in China, when intellectuals were invited to critique Mao, only to be sent into exile. Ai Weiwei’s father was a famous poet, who was sent to clean toilets in the Gobi desert.

The final installation “Yours Truly” appropriately placed in the dining hall of the prison, offers an opportunity to correspond with political prisoners: post cards are pre addressed to the people featured in “Trace.” We can tell them directly that we are thinking of them. It is surprisingly moving to reach out personally to those imprisoned, and know that even this simple act of communication can break through the devastating isolation of those lost in a prison or detention system.

Set inside the infamous Alcatraz prison, in the middle of the overwhelmingly beautiful San Francisco Bay, with cormorants and gulls flying around us, intensifies the experience of @Large as it calls attention to the huge injustice of politically motivated imprisonment worldwide.

Alcatraz itself had its share of political prisoners as well. In addition to the Hopi, conscientious objectors from World War I went there. Alcatraz is mainly famous for the prisoners who arrived after it became a federal prison for the “worst of the worst” in 1933.That is what the tour seems to emphasize.

Ai Weiwei, with the help of an unusual coalition of public and private organizations, has pulled off an enormous coup in @Large. The installation layers image and symbol, fact and metaphor, freedom and detention; it includes history and the larger contexts of imprisonment and human rights. The media of kites, and Lego and porcelain, as well as music, poetry and chants, underscore the fragility of freedom itself. Ai Weiwei has had his passport revoked by the Chinese government, but his outspoken protest of unjust imprisonment and detention and his stand for freedom cannot be contained.

“Any artist who isn’t an activist is a dead artist.” Ai Weiwei

This entry was posted on May 18, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Contemporary Art, Detained, dragons, global justice, Uncategorized.

Rameschwar Broota and Nalini Malani at the Kiran Nadar Museum in Delhi

On our first afternoon in India, we started with two world famous sites, the stunning Humayun Tomb (1565), the forerunner of the Taj Mahal and two newly restored nearby tombs, all part of an extensive necropolis in that part of Delhi. Then we went on to the Qutb Minar (1190), a minaret surrounded by a mosque made of recycled Hindu temple pieces.

But I was most excited to visit director and curator, Roobina Karode at the spacious Kiran Nadar Museum.

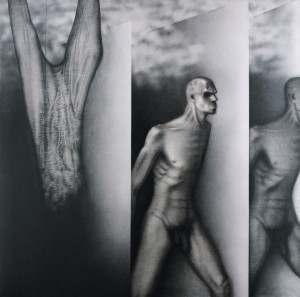

There we immediately immersed ourselves in the large scale paintings in the career retrospective of the work of Rameschwar Broota,”Visions of Interiority: Interrogating the Male Body 1963 – 2014.” In person, Rameschwar is soft spoken and understated. As he took us through the exhibition, he described his work in a quiet voice that belied the extraordinary experience of the works themselves.

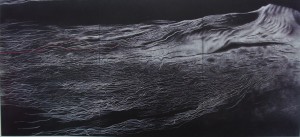

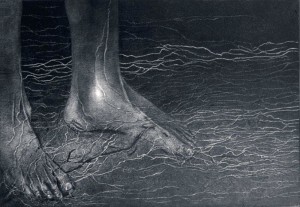

The first paintings we encountered seem to swell and flow on the wall, water, bodies, landscapes (I wish this was a bigger image, I am offering you a detail also here). But the undercurrent is both beautiful and threatening. Because of the large scale, and the subtle emergence of the body only in parts, in white lines on a dark ground, I felt unmoored, as though these works were creating a new world of which I was not a part, but which might envelop me.

Aside from the scale and imagery, the meticulous process that Broota has invented to create these works requires enormous physical stamina and discipline (some of them refer to principles of yoga, a practice he follows). He paints many transparent layers of close valued paint, silver,sepia, blue, black on the surface, then draws the imagery by scratching with an ordinary razor blade. The thin white lines emerge from the darkness and coalesce into the eerie flows.

The sense of continuity between the liquid coursing through veins in a body and the water flowing in the sea was unnerving. These works for me suggest the impending and ongoing ecological crisis of the planet. Its details emerge clearly, a foot, a body within the flow, but the overall scale is beyond us, beyond the canvas, stretching into a larger world. These works are referred to by the artist as “Traces of Man” or “Metamorphosis” in which the human figure is part of a huge environment.

Broota focuses on a vulnerable male body. Much of the art in India is based on the female figure, heroic males or mythological creatures. These works are explicitly male (except for one based on his wife). In another series called “Runners” from the 1980s we see a lonely man separated from the world, seemingly existentially running or standing, or hanging upside down. “Prisoner of War” somberly presents an anonymous and generic prisoner.

Earlier work by the artist is more explicitly political. One series from the 1970s refers to politicians by using apes, in various amusing and cynical postures, as in “The Same Old Story.” Still large in scale, these satiric apes perfectly represent the political process in its self serving and and self referential narcissism.

The curator states:

Broota’s ‘Man’ in his primeval presence goes through the ambivalence of body and being, spirit and matter, fragility and resilience. With the trepidations of age, time, death and disintegration, one encounters the presence of male vulnerability in Broota that pushes the heroic male to often acquire an anti-heroic position.”

Broota, together with his wife Vasundhara Tewari Broota are both long time art teachers at Triveni Kala Sangam, the historical Delhi art school, founded by Sundari Shridharani in 1950, and designed by Architect Joseph Stein . Today it still has free classes. Rameschwar has been Head of the Art Department there since 1967.

Vasundhara is also an outstanding feminist artist. I was able to visit her studio on the following day. Here is an example of one of the paintings. She has recently shifted from small figures to very large ones. This painting of her daughter titled “Eye of the Tiger” 2012 suggests the emotional turmoil of adolescence. Its off center composition and layers of different moods are a stark contrast to her earlier work of women practicing centered yoga poses. But looking at her facebook, it appears that taking chances with many different types of images is characteristic of her work.

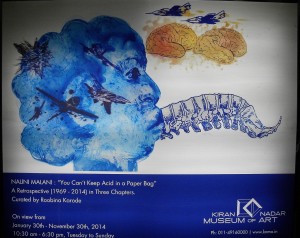

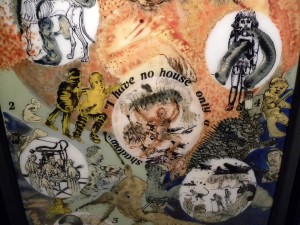

At Kiran Nadar, we also saw the last part of Nalini Malani’s retrospective “You can’t keep acid in a plastic bag.” This section’s title referred to her often referenced mythic women “Twice Upon a Time: Cassandra, Sita, Medea.” Malani seems to also follows science fiction: this image with its huge centipede like creaturecoming out the mouth reminds me of the symbiot people had inside them in the tv show “Stargate.”

Malani’s pioneering medium, reverse painting on mylar, here displayed in five adjacent and interconnecting panels (more usually on rotating cylinders with lights shining on them so that they project moving shadows) creates an unsettling presence, her work cannot be seen as material, the imagery seems to be changing before our ideas. Malani layers many literary and visual sources including pre Mughal frescoes from Rajasthan, Greek mythology, Western art, Indian history, Chinese art, evocative but unidentifiable botanical and biological creatures, (Nalani’s earliest drawings and watercolors were inspired by biology and botany ), her invented monsters, and much more.

For decades Malani has engaged deeply disturbing social issues through the representation of the human body such as in the “Mutants,” series about the horrifyingly deformed babies born after the Bikini Atoll nuclear tests.

In “Twice Upon a Time” monsters lurk, the earth seems to be enclosing many crawling creatures that suggest centipedes and worms or skeletal animals; oversize and overweight male figures, human or subhuman, occasionally dressed in a suit, suggest violence. Airplanes threaten pilgrims.

Andreas Huyssen, one of my favorite critical thinkers describes them thus

“It emphasizes the fragmentation and debasement of human form, but it does not suggest a currently fashionable anti-or post-liberating escape… there is no romanticization here of some otherness… nor is it… a take on the once fashionable Western exploitation of the abject. It is rather a way of registering and visually transforming the real violence and mutilations of the human , in specific historical and by now global contexts, without ever violating what once could call an ethics of the gaze on violence.” ( Nalini Malani In Search of Vanished Blood, Hatje Canatz documenta 13, 54.

In other words, Malani never loses her own direct emotional response to what she is representing and neither do we. We deeply feel the disintegration, disruption, deterioration of the planet, of the human condition as we look at her work.

Malani herself became a refugee from Pakistan, when she was only a year old at the time of the Partition of India and Pakistan, but it was not until the 1992 attack on the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya by Hindu mobs that she returned to that memory.

“In Search of Vanished Blood” a poem by Faiz Ahmed Faiz quoted by the artist conveys the nightmare of violence that leaves no trace. Here is a short excerpt:

“There is no sign of blood, not anywhere.

I’ve searched everywhere.

The executioner’s hands are clean. His nails transparent.”

This poem is one point of departure for her astonishing work of the same title at Documenta 13. Another reference point for this work is Cassandra by Christa Wolfe. The voice of Cassandra speaks in the sound track of the installation which creates an immersive environment of rotating mylar cylinders that create a frightening shadow play.

For many decades, Malani has addressed violence, political and personal, as well as cultural. Recently she has been horrified by the manipulation of Gandhi’s philosophy for political power and violence by the now Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi (who allowed the riots to rage unchecked in Ayodhya and even to encourage them.)

I first saw Nalini Malani’s work at the 2003 Istanbul Biennial installed in the huge underground Roman era cistern, a fitting place for her work, with its shadowy distances punctuated by heavy columns and eerie lights. I remember the moving mylar cylinders with mythical references that projected on a wall like a shadow play: As I wrote at the time:

“Nalini Malani’s work in the Yerbatan Cistern was magical. Her rotating circular acetate discs projected overlapping sequences of the shadows and reflections of fantastic beasts interspersed with guns and skulls on the wet floor, wall, ceiling. Projected against this was footage of the bombing of Hiroshima during World War II. Malani’s work took time to penetrate. The first impression was soft colors, light, and music. But as the bombing interrupted it, the fantasy world was psychically invaded by death and destruction.”

Malani’s embeds her work in deep philosophical roots. One of those roots is based on her formative years in Paris in the late 1960s when she came in contact with Simone de Beauvoir and other major thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Luis Althusser, and Roland Barthes.

Malani is acutely aware of her privilege created at the expense of the backbreaking labor of others, a situation so obvious in India where the medieval and the contemporary still exist side by side, the oxen pull the plows, as the wealthy drive the cars. As she has put it “I had a studio in a wholesale electric bazaar, and for me, the anomalies were that a lot of high tech instruments were being carried by porters on their heads. These people made homes without walls on the pavement, and during the rains they used the packing material that came from the boxes of high tech computers and sound systems to protect themselves from the rain.” ( 18 In Search of Vanished Blood)

Nalani provided a cover illustration for Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence, Voices from the Partition of India, (Duke 2000) one of the most intimate and revealing studies of the devastating impacts of the Partition on women, children and families. That silence is the foundation of consent and amnesia. The Partition is a blatant example of the power of arbitrary political decisions to cause death and trauma. But its after effects have only recently been exposed, unlike our ongoing wars everywhere in the world.

Malani and others are breaking that silence by actively creating space for us to begin to understand not only that atrocity, but also other nightmares that have resulted from political violence. That she uses mythic sources such as Medea and Cassandra, as well as Sita, all women who suffered at the hands of men, emphasized the global oppression of women. Mythic sources come out of cultural sources, emerge from society’s subconscious.

Broota and Malani both confront us with large ambiguous spaces and unsettling imagery that does not allow us to peacefully experience their work. They embed their art with different aspects of the vast Indian history and philosophy, but their art also joins the current global conversation on the state of the earth and whether we will continue into the future.

This entry was posted on March 25, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Contemporary Art In India, Feminism, Feminism, Uncategorized.

A valuable conversation of past and present: Three Special Exhibitions of Indigenous Art in Seattle

Last night I went to the Duwamish Longhouse just south of Seattle for a poetry reading that included Sasha La Pointe, the granddaughter of Vi Hilbert, the great savior of the Lushootseed language, whose portrait hangs in the lobby of the longhouse. Sasha has a lot of presence. What a proud history she has to draw on as a poet!

We are richly endowed in the Northwest with contemporary Indigenous artists working in all media. Fortunately we have two art museums here with a significant commitment to presenting their art. Currently, both the Seattle Art Museum and the Burke Museum are offering a valuable conversation between past and present Indigenous artists. As with all conversations, the complexity of these relationships emerge only gradually.

In spite of all of our efforts to brutally obliterate them in every way possible, indigenous people survived along with a few of their artifacts such as the magnificent work in the The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection on loan to the Seattle Art Museum from the American Federation of the Arts. Historic works like these along with their mythic stories handed down by word of mouth, as well as such surprising sources as Edward Curtis, enable contemporary Native artists to honor, revitalize and reinvent their past. The variety of media, content, and layers of history give the works both a compelling presence.

Sometimes those traditions have been re excavated only since the 1980s as in the case of the Yup’ik people of Alaska. Sometimes the artistic and cultural traditions have been known since the turn of the 20th century, when even at the height of cultural oppression, a few artists continued to work, such as Charles Edenshaw.

Figure (Pendant?), 3rd–13th centuryAncestral Columbia River people, Washington State or Oregon Antler 10 1/8 × 3 × 1/4 in.Diker no. 529

Courtesy American Federation of Arts

A few of the works on display at the Seattle Art Museum are amazingly early, such as this piece from the Columbia River Basin. Look for the other Columbia River partner piece from the 19th century that has a “she who watches” image on it, taken from the painting on rock near the Dalles from thousands of years ago, and a major theme for contemporary artist Lillian Pitt ( not included in the exhibition)

In other cases, much has been completely lost, but contemporary indigenous artists find ways to save what they can and re interpret it, as in the annual canoe journeys that have recently allowed tribal groups to gain a new sense of communal identity.

Preston Singletary

The rattle that sang to itself, 2010 Blown, Hot sculpted and Sandcarved Glass, Steel Stand 19 X 11 X 6 Inches, Photograph by Russell Johnson Courtesy of the Artist

Preston Singletary transforms a raven rattle from wood into glass, adding his own interpretations that are steeped in respect for tradition as well as contemporary life. (The piece illustrated is similar to the one in the exhibition.)

Reverence for the natural world has led many indigenous people to the activism necessary to save us. Happily, white environmental activists are now joining with them as never before

Mask, 1916-18

Yup’ik, Hooper Bay, Alaska Wood, pigment, vegetal fiber20 1/2 × 14 × 8 in.Diker no. 788 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

In the first gallery of the Seattle Art Museum’s “Indigenous Beauty: Masterworks of American Indian Art from the Diker Collection.” wooden Yup’ik masks from Alaska honor each creature that had been killed during the hunting season. They were given away each year, unlike so many other works in the exhibition that were made specifically for sale to tourists.

Organized as clusters of different media ( and do take note of the extarordinary range of different materials here), the exhibition includes works from the Western Arctic through to the Woodlands of the East Coast.

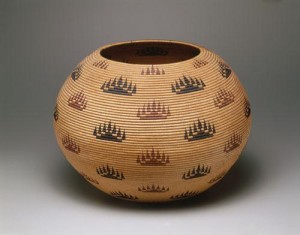

Some are quite familiar to us such as baskets from both California and the Plateau tribes, but we dramatically see the impact of white traders in the increased scale and new designs. Best known is Louisa Keyser who successfully pioneered large baskets with new motifs and new combinations of materials at the turn of the twentieth century.

Louisa Keyser (also known as Datsolalee, Washoe) Carson City, Nevada

Basket bowl, 1907

Willow shoots, redbud shoots, bracken fern root 12 1/2 × 16 5/8 in. Diker no. 326 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

Katsina dolls made by the Hopi were meant to be very personal to an individual, and only with persuasion did the Hopi create Katsinas for sale to tourists. This ogre Katsina is one of them. Since the original purpose of Katsinas is to provide an individual with guidance on how to lead a good live, this obviously was not made for that purpose.

Qötsa Nata’aska Katsina, 1910-1930 Hopi, Arizona

Cottonwood, cloth, hide, metal, pigment

18 1/2 × 6 × 10 in.

Diker no. 831 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

Beaded regalia which began after contact with white traders was taken in elaborate directions in both design and color by the Plains and other Indian groups such as here the Nez Perce from Idaho. This shirt would have been made before we started chasing those tribes North and stealing their land in the 1870s ( at the same time that Yellowstone National Park was created).

Man’s shirt, ca. 1850 Niimiipu (Nez Perce), Oregon or Idaho

Hide, porcupine quills, horsehair, wool, glass beads, pigment

32 11/16 × 60 2/3 in. Diker no. 666 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

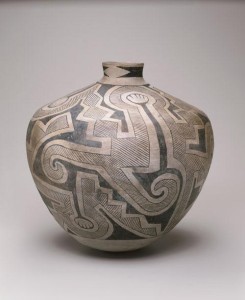

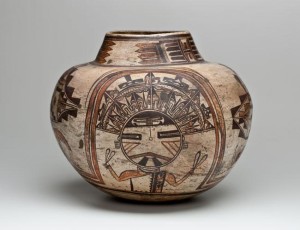

Historical continuity mixes seamlessly with innovation. An exceptionally large pot by Hopi artist Nampeyo from 1900, was built with coils rather than on a wheel. It features a mixture of archeological references and contemporary inventions. Nearby is an anonymous water jar from 1150 painted with a large hand in the midst of abstract patterns, an absolutely unique object.

Water jar, ca. 1150 Ancestral Pueblo, New Mexico

Clay, slip15 1/8 × 15 7/8 in.Diker no. 313 Courtesy American Federation of Arts

Nampeyo (Hopi-Tewa) Hano Village, Hopi, Arizona

Water jar, ca. 1900 Clay, slip12 × 13 1/2 in.Diker no. 824Courtesy American Federation of Arts

The Seattle Art Museum partnered the visiting Diker collection with “Seattle Collects Northwest Coast Native Art” which is also filled with surprises. Look for the unique argillite piece collected by Bill Holm, the eminent and groundbreaking art historian of Northwest Coast Indian Art.

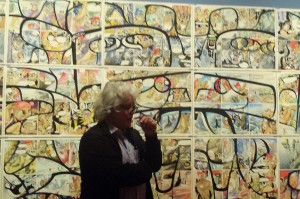

The large painting by Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas stands out in “Seattle Collects.” It combines Japanese Manga style and native Haida art motifs. Yahgulanaas dynamically explained his work in terms of form, history, and storytelling ( Red: a story of the punishment that results from a life lived for revenge). The artist is also one of the original Haida to resist logging on ancestral lands in the 1960s.

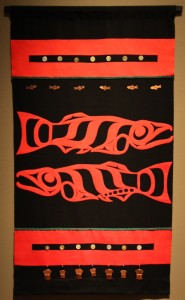

Unknown artist Tsimshiam, yellow cedar, operculum shell, paint 19th century Burke Collection 2252 Purchased from George Emmons and David Boxley Tsimshiam, Feast Dish yellow cedar, operculum shell, paint on loan from the artist

Equally provocative is the Burke Museum’s “Here and Now: Native Artists Inspired ”subtly installed by the museum’s designer Bridget Calzeretta. Based on the unusual concept of a living museum collection in which contemporary artists are encouraged to interact with specific objects, the exhibition marks the 10th Anniversary of a program at The Bill Holm Center that provides financial support for native artists to visit the collections. They don’t just look, they handle the art works, and they feel their energy transmitted to them. As Alison Bremmer put it “I was hit by the energy I got from the piece. I think the artist who made it would be really proud to know that it still carries that feeling all these years later.”

The Burke discovered that, after their visit, the artists’ work changed. In a dramatic demonstration of the impact of a program, they are pairing the work that most inspired a specific artist with a corresponding contemporary work. The result is a subtle and fascinating conversation between traditional art and contemporary arists. The contemporary works include close copies of older works in order to keep the traditions alive, creating a contemporary art work with the same materials and making a contemporary painting that directly connects to our culture.

David Boxley did a copy of a Feast Dish (see above). He declares “The original artist was really really good. It’s always been an inspirational piece for me . . . we all follow the same two dimensional design rules and what makes one artist different from the next is how he interprets his style into that strict set of rules.”

Lou-ann Ika’wega Neel created a contemporary art work of felt, suede, copper and abalone buttons, all traditional materials, inspired by a traditional wool cloth, one of the earliest acquisitions of the Burke Museum.

Sonny Assu Ligwilda’xw Kwakwaka’wakw #polatch shades of gray, acrylic on canvas, on loan from the artist and Equinox Gallery

Sonny Assu starts from historical regalia to create an abstraction that incorporates ipods: “ Having my great-great-grandfather Chief Billy Assu’s Chilkat regalia placed on my shoulders was part of the inspiration for this painting. This piece compares chiefly nobility – embedded with the knowledge and wisdom of his years as a chief – to how we formulate social status today through consumerism, branding, pop culture, and social media. “

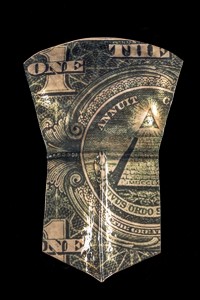

Alison Bremner based a work on the traditional copper Tinnah, an object exchanged at potlatches as a sign of generosity and status. She painted it with the “all seeing eye” of Satan from our dollar bill, marking it with the money economy that supplanted its historical purpose.

Nothing could be more apt to “Here and Now” than the original Eagle mask that inspired the Seahawks logo in the mid 1970s, borrowed just for this exhibition. The wooden mask would have been worn in a ritual dance. In the midst of the dance, it opened to reveal the ancestor of a family group. The logo connects one of the most popular rituals of our contemporary world to one of the fundamental rituals of the indigenous Northwest.

As a finale of “Here and Now” a woven work by Tommy Joseph incorporates the logo of Idle No More, the crucial environmental activist movement based in Canada.

From the Yu’pik mask, honoring the animals killed in a hunt, to Idle no More, honoring the earth by resisting its rape, this cluster of exhibitions, provides the continuity of indigenous cultures over thousands of years, its compulsions and rituals, its complex techniques, and its extraordinary creativity. They underscore that this creativity is embedded in a reverence for the interconnected spirits of the natural world that provides us with a crucial perspective. If we listen to this conversation and take part in it, we may find a way forward from our current crisis.

This entry was posted on March 20, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Contemporary Art, Contemporary Indigenous Art, Culture and Human rights, indians, Indigenous Art, Lillian Pitt.

“Permanent War: The Age of Global Conflict”

On September 11, 2001, privileged white Americans in New York City finally experienced what people of color everywhere already knew: civilian life in the US thinly masks a massive military endeavor that perpetrates death all over the world. On September 11, it backfired on us and erupted in our midst, physical and unavoidable. Likewise, the protests over police murders, #Black Lives Matter, highlighted our militarized police state, exposed and documented by smart phones.The hardware from wars streams directly into local police forces and into our lives.

Technology changes the experience of war, making it both more immediate and more detached.

“Permanent War: The Age of Global Conflict,” an art exhibition at the Boston Museum School Gallery curated by Pamela Allara, confronts us with artists who address the continuous presence of military actions past and present on the globe today. More than that, though, it focuses on the new dehumanization of war through technology.

We already know that our children and grandchildren need astute parenting to avoid being inundated by the military paradigms that penetrate every aspect of popular culture in games and toys and films and Hallowe’en costumes. Even more insidious, “war games” prepare them for the real thing. Of course, that is not new. How many of us played “cowboys and Indians” as children!

Pamela Allara states in her introduction to the exhibition: “If one is to judge from the artistic record provided by museum, human history has been synonymous with constant warfare. . . . the United States has based its economy on maintaining military dominance. However, the goals of our military interventions remain vague, as the many conflicts surfacing world-wide rarely have clear lines of demarcation between right and wrong, totalitarianism, or freedom. In addition, due to increasing mechanization, the very nature of warfare has changed, further challenging the concept of a ‘just war.’”

I am reading a history of non-violence at the moment and the author points out that there is no word for that concept in any language, except as the negative of violence. Gandhi tried to create a word, “satyagraha”(“truth forces”) but it did not gain traction. The author, Mark Kurlansky, also points out that the concept of “just war” came from St. Augustine, as an “apologia for murder on the battlefield. He declared that the validity of war was a question of inner motive. If a pious man believed in a just cause and truly loved his enemies, it was permissible to go to war and to kill the enemies he loved because he was doing it in a high-minded way” [i]!!!

The loss of a semblance of a consistent reference point for a “just war” (what Christianity used to be) underlies the ever shifting “high-minded” explanations for war today. In this exhibition, it includes Euro-US wars from the late nineteenth century to the present moment and around the world.

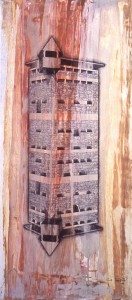

The chronological point of departure is Paul Stopforth’s Empire Building based on a stone fort from the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 – 1902. A great pun, the title refers to the European resource grabs in Africa. The technology of surveillance has not changed much since then in terms of its principles. Stopforth doubles this austere tower and makes no exit for the oppressors.

Paul Emmanuel, 3SAI: A Rite of Passage, 2008

Still from high definition digital video.

Courtesy of the artist.

Another South African, Paul Emmanuel addresses the present in that country in his video that witnesses the dehumanization of entering the military. After his head is shaved, the cheery blond becomes a frightening skin head, losing his individuality entirely. This relatively minor act of transformation signifies the much larger loss of humanity that people undergo as they enter the military.

Sig Bang Schmidt and Steve Dalachinsky, The Great War (WWI), 2002–04. Detail from the book of WWI photographs overpainted digitally (Schmidt) with accompanying poetry (Dalachinsky).Courtesy of the artist and the poet.

A collaborative work between poet Steve Dalachinksy and artist Sig Bang Schmidt, goes back to World War I for its source photography as they address in word and image the unchanged nightmares of war.That mechanized war perpetrated horrors on humans and cities beyond anything previously imagined. But from our perspective today, the “war to end all wars” seems short: 1914 – 1918, only four years. And it actually ended, albeit with a treaty that led to the next war.

Matthew Arnold, Artillery Emplacement, Bunker Z84, Wadi Zitoune Battlefield, Libya, 2012 from

Topography as Fate: North Africa Battlefields of World War II series.. Courtesy of the artist.

Recently Matthew Arnold revisited sites of World War II in Libya, and found derelict bunkers still in the landscape. Aside from the fact that we barely think about North Africa when we remember World War II, you can hardly see the bunkers in this photograph, all the more chilling as a comment on the meaninglessness of war.

Bonnie Donohue, Bunker in a Storm, Vieques, Puerto Rico, 2005. Archival Digital Print. Courtesy of the artist

Bonnie Donohue presents another site of derelict World War II bunkers in Vieques Puerto Rico, an American military base built on land expropriated from local people in 1941. Her entire project, installed in these bunkers, explores the “cultural, economic and health consequences of the U.S. Navy’s sixty-year occupation of Vieques, Puerto Rico as a military base and bombing range.” She even found a person who described the inhumane orders that forced his family to pick up and move their small shack themselves when the US arrived with its “just war,” right after the Pearl Harbor bombing. Only after massive protests, did the US finally leave Vieques in 2003.

These three works are in the section of the exhibition called “Landscape as Cemetary,” a potent description. That theme builds on American art and its tradition of land as a political site in the movement West, but with a new twist in the works of Donahue and Arnold with their lugubrious bunkers.

Another theme in the exhibition is “Living with War”which includes more recent wars and their ongoing damage.

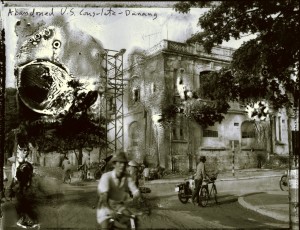

Bill Burke, Abandoned U.S. Consulate, Danang, 1994. Gelatin silver print from a Polaroid negative..Courtesy of the Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

In the 1980s Bill Burke visited men who continued to identify with their past as the part of the genocidal Khmer Rouge that terrorized Cambodia from 1972 – 1975. The former soldiers are still proud of “their weapons and terrorist strategies”. In this photograph damage in its development echoes exactly the long term damage in people’s lives and minds caused by that fruitless “domino theory” war in Southeast Asia.

Lamia Joreige, one of a group of artists who emerged in Beirut just after the long Lebanese Civil War (1975 – 1990), presents us with the repetitive damage of war under the theme “Combat as Performance”. Her three channel video based on archival photographs, reenacts a woman running on one screen, a man dying on the other, and the sea tinged with red in the center. The deadly repetition of terror and death for ordinary people caught in a war zone speaks to yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Its antecedent is Picasso’s Guernica, the first artistic representation of what is today a continuous reality, bombing from the air of unsuspecting innocents. But Joreige does not convey terror, only the repeated act of running and dying. Its unemotional re-creation echoes the detachment we have from the reality of bombing, which we so briefly experienced on 9/11.

Claire Beckett, Marine Lance Corporal Nicole Camala Veen playing the role of an Iraqi nurse in the

town of Wadi Al-Sahara, Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, CA from the Simulating Iraq Series,

2008. Archival ink jet print. Courtesy of the artist and the Carroll and Sons Gallery.

Claire Beckett presents another type of performance in a simulated Iraqi village built by the US military as training camps in a California desert. Beckett features the play acting in which veterans or out of work actors play the parts of terrorists or devout muslim women. The contrivance of these scenes as the actors break for lunch clearly exposes the arrogance and stupidity of the exercises.

Harun Farocki, Serious Games II: Three Dead, 2010. Still from single-channel video. 8 min. Color,

sound. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York.

Haroun Farocki’s Serious Games II is based on virtual reality military training tapes, under the theme “Conflict as Media Entertainment.” These eerie robotic scenes clearly manifest that “just war” is making the world safe for commodity capitalism: we see Coca Cola signs hanging in the street. The absurdity of the actions, the us and them paradigm (in this case the other is barely represented), and the final victory scenes with tanks rolling into the town, clearly convey our hubris. But Farocki’s also emphasizes the difficulty of distinguishing simulation, fact, fiction and reality as a result of the invasion of technology into war in all its aspects.

Richard Mosse, Killcam, 2008. Still from video. Courtesy of the artist and the Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Richard Mosse’s juxtaposition of veterans playing video games in a hospital with drone videos (again pirated) of actually killing people by remote control. We watch the drone drop its massive, multimillion dollar payload bomb (reduced to a puff of smoke) on a remotely observed human being, assumed to be a terrorist by someone operating the machine in Utah. Then the screen switches to the veteran with a joystick killing in a simulated Middle Eastern village.

Coco Fusco, Operation Atropos, 2006. Still from single channel video. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York. © Coco Fusco/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Training for torture is Coco Fusco’s topic: she and a group of women enlisted in an actual torture training program using techniques developed by the US military to teach soldiers to resist being tortured. Here, we have training that is all too real, but at the same time it is a performance. The women who participated felt its horror, and many of them could not complete the program, even though they had volunteered to participate. The line of reality, simulation, fact and fiction is erased when people experience the brutal methods of interrogation that have become standard in today’s military.

At the same time, the lackluster response to the recent CIA report on our standard practice of torture, demonstrates how innured we are to it. Guantanamo Diary, by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who has been detained for twelve years and is still not released, was recently published. It is a first hand account of torture hand written by Mohamedou in English that he has learned while in detention. Its heavily redacted text and years of legal actions to get it published speaks volumes about the CIA desire to prevent any first hand understanding of our technological wars. I am currently reading this riveting book. It details torture in its minutiae: day to day deprivations by heat, cold, sound, pain, hunger, insult, nudity and bodily function. Sign the ACLU petition to free him!

While some torture techniques are ancient, some, such as shocking the victim with electricity, also relates to another chilling theme in the exhibition, “Mechanized Bodies.”

We have seen mechanized bodies in the photographs of what a soldier wears today in terms of protection, armor, firepower, and vision equpiment. Ken Hruby, Adam Harvey, and Trevor Paglen take the idea in new directions ( The work by Paul Emmanuel discussed above is also in this group).

Ken Hruby, Short Arm Inspection, 1993. Detail from mixed media installation with plumbing parts Courtesy of the artist.

Hruby’s distrubing/humorous constructions called “Short Arm Inspection” suggest prosthetics, dismemberment and a subtle type of torture (the short arm is the penis, inspected by Drill Sargents in demeaning ways). Even as we laugh, we get the point of the extreme discomfort these inspections would have caused.

Harvey has created anti drone clothing that confuses heat detection technology (of course, in reality people have low cost substitutes like woven straw in Yemen and elsewhere).

Trevor Paglen, a geographer and an artist, obtained pirated video from a drone, its impersonality chilling, even as we know it is operated by a human being. He makes depersonalized drone warfare visible through its technology. But his concept reflects his training in geography, as he refers to the “infrastructure” needed for this type of warfare: “You end up developing a state within a state that has very different rules and different ways of operating than what we would think of as a democratic state.” He wants to help us “see secrecy.”

Most moving of all is Iraqi Jamal Penjweny’s video Another World (2013). I conclude with this work, as it is not simulated, it is footage of real people. Penjeweny filmed young men smuggling alcohol into Iran. It includes interviews with the men explaining the desperate financial conditions that led them to pursue this dangerous occupation. Shortly after the film was made, two of these men died. The reality of these deaths, what our immoral political leaders call “collateral damage” brings home the actual on the ground effect of war. For all our technology, the human body is subject in war to forces beyond its control and ultimately many people are dying because of that, including these young men.

“Permanent War” presents the repeated destruction and instant death of war enabled by contemporary technology. It explains our detachment from the realities that people today in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Lebanon, Syria, and so many other places (Yemen for example) live with every day, as the drones perpetually buzz, bomb, and kill. We are permeating our society with permanent military culture. Thanks to this exhibition, we are now more aware of some of its insidious methods.

Permanent War: The Age of Global Conflict” is at the gallery of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston January 29 – March 7 2015

[i] Mark Kurlansky, Non-Violence The history of a Dangerous Idea, Modern Library, 2008.

This entry was posted on February 25, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in Beirut, Art in War, South Africa, Uncategorized.

Rodrigo Valenzuela, the 13th man and the end of Utopia

Rodrigo Valenzuela’s “Future Ruins” exhibition at the Frye Art Museum aptly characterizes where we are at this moment in Seattle, and in other cities that are tearing apart their historic urban fabric in order to cater to the rich with high end housing.

Rodrigo Valenzuela

Hedonic Reversal #13, 2015

Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum and funded by the Frye Foundation

Rodrigo Valenzuela

Hedonic Reversal #1, 2015

Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum and funded by the Frye Foundation

In his large installation Hedonic Reversal, Valenzuela presents us with constructed modernist ruins, with off kilter perspectives and installed as though in the midst of a construction site with shadowy ghosts of collapsing buildings painted on the wall. Here is a short video that sets the tone as he was creating the work http://www.rodrigovalenzuela.com/

He carefully explained his process, chalk, styrofoam strips, to suggest collapsing buildings, rephotographed over and over, but that has little to do with the overall significance of the works and the installation as a whole.

We see here the end of modernism, the collapse of utopia, the final chapter in a cycle that began with the Constructivists in the early 20th century. Artists like those of De Stijl, and the Russian Constructivists believed that art could build a new society, they idealized worker housing as a humane place, scaled to ordinary people, with usable spaces and shared community.

Yesler Terrace in Seattle is based on those ideas. Yesler Terrace is a community with shared public spaces and small scale. It was the first integrated public housing in the country. It is being torn down in order to make way for new market rate housing and high rises.Several enormous towers are being built on a part of the land sold way under market value to Vulcan, Paul Allan’s company. When Yesler Terrace was built it represented a utopian principle in action. Now its destruction stands for the end of those principles.

El Sisifo, 2015

3-channel digital video Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum and funded by the Frye Foundation

The video installation titled El Sisifo (Sysiphus) films workers as they pick up garbage after a game. . Sisyphus, the well known Greek story, tells of a king who was punished for deceitfulness by being forced to roll a heavy boulder up a hill only to have it roll down again. It suggests the repetitiveness and meaninglessness of the efforts of these workers punished with minimum wage or below because they have been accused by our society as poor people, as workers, as undocumented migrants. The rich accuse the poor and the poor follow a continuous round of mundane labor that serves the rich.

They are the 13th Man, as Rodriguo puts it, after the 12th man (the fans, the public) leaves. He films up close to a single worker with his uniform for a “cleaning service” (a service industry notorious for its exploitation of non union labor). The worker conscientiously finds every cup left behind and puts it in a garbage bag. But the artist also maintains a larger context, as he films from a distance: the tiny, anonymous workers move through the empty stands almost as though choreographed.On one of the videos a worker diagrams his route through the stadium, a dizzying set of movements.

The background sound track of “Pep talks” by sport coaches create an eerie contradiction to the silence of the stadium.

Rodrigo Valenzuela

Diamond Box, 2012

Digital video with audio (4 minutes)

Courtesy of the artist

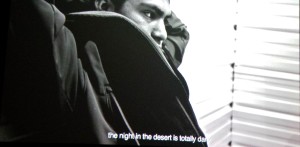

Rodrigo

Rodrigo addresses worker issues in two other works. Diamond Box films the undocumented day laborers who stand by the road waiting for work. They are filmed in an anonymous studio setting, silent, but accompanied by a soundtrack of the stories of crossing the border, and their lives here. Their words are recorded in subtitles in English. It is a moving work, as the film protects the identity of the workers, underscoring their silent place in our economy, at the same time that we listen to their unbearably painful and hazardous life. By disconnecting the words and image, by having the workers simply sit silently, we sense the distance between what we can understand, what can be documented, and what has been experienced.

Rodrigo does not hide his elite intellectual approach to worker subjects. He came here as an undocumented migrant himself, but with an art degree and carpenter skills, and he describes reading Kant at lunch as a worker on construction sites. Later, he realized that the stories of his fellow workers were extraordinary. He mentioned to me that many of the day laborers have degrees as plumbers or technicians, but they have lost all possibility of professional employment by coming here, and often live in shelters in a state of deep depression.

A third video Maria TV addresses female domestic workers (nannies and maids) in a “Playback Theater” format which is described on Wikipedia as follows:

“Someone in the audience tells a moment or story from their life, chooses the actors to play the different roles, and then all those present watch the enactment, as the story “comes to life” with artistic shape and nuance.”

Rodrigo starts the piece with an excerpt from a TV “novella” about a woman who is told to leave her child forever, a strange echo of the real tragedies of separation that women choose when they leave their families behind in order to make money in the United States to send to their children. (They always believe they will be gone only a short time, but usually stay for many years. Enrique’s Journey by Sonia Nazario is the story of one of those children coming North to find their mother and what happens after they are reunited). The actresses enact both the melodrama of the novella and the real anger and frustrations of the domestic women.

The artist declares that he is functioning at the border of documentary and fiction. His own experience of crossing the border is never told as a narrative although sometimes he seems to refer to it as in “Walk by Night” which films the desert day and night from a moving vehicle. It is not clear if the artist actually walked across this desert or is re imagining this space as one which has been crossed by so many migrants.

Rodrigo Valenzuela is attracting a lot of media attention and awards. He is well on his way to being an art star. His subject matter of the undocumented workers and their lives and (nonexistent) homes is distant from his present life in the United States (He gained citizenship by marrying).

One hopes that he doesn’t lose his soul in the glitz of art market success. The people and places he has been representing come out of the shadows of accusation, cliche, prejudice and exploitation. His success can hopefully enable him to cast an even stronger light on the human beings who stand so heavily accused in our society, but without whom our culture would collapse, to become ruins much like that vision of the future suggested in Hedonic Reversal. I still remember May Day 2006, the largest immigrant march to that date, when downtown Seattle came to a standstill as immigrants marched for their rights.

This entry was posted on February 7, 2015 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, Conceptual Art, Contemporary Art, Culture and Human rights, democracy, economic imperialism vs democracy, Performance Art, Photography, Uncategorized.

Delhi Feminist Artist Gogi addresses the 2012 Gang Rape of Nirbhaya

ALTAR FOR NIRBHAYA by Gogi Saroj Pal

“At the heart of Gogi Saroj Pal’s art is the understanding of female complexity” ( Mary-Ann Milford-Lutzker in Gogi Saroj Pal, The feminine unbound, Delhi Art Gallery, 2011)

Gogi Saroj Pal, a radical feminist artist based in Delhi, India has spoken out about the contradictions for women in India for many years. Her most recent series “Altar for Nirbhaya” is dedicated to the 23 year old victim of gang rape in 2012. Nirbhaya, meaning “courageous one” is a pseudonym for the name of the victim. She was raped on a bus in Delhi enabled by a bus driver who drove around the city for over an hour while five men raped her after attacking her boyfriend.

It is a horrifying story. Two weeks later she died. What makes the story all the more upsetting is that she had hoped to provide free medical care to the poor after she finished medical school. Her family is poor, they had worked hard to enable her to get an education.

Her story ignited rage all over the world. But now three years later, we have all stopped thinking about her. Gogi’s paintings remind us vividly of the violence of that attack and the death of the victim. The sickle at the center piece of several works refers to an attribute of Kali, the Goddess of Destruction.

The contradictions for women in India loom larger than any other country in the world. As Gogi has said

“Our mythology is crooked and so is our mentality,” says Pal. “As we celebrate Navaratri [Hindu Festival of Lights in honor of Durga the universal mother], we also kill a girl child, and as we worship goddesses for money, we continue to rape our women.”

Indeed, in India the worship of Durga is a hugely popular festival, Durga is regarded as the universal mother. Goddesses in general prominently figure in Hindu mythology and daily ritual practice: there is Lakshmi, Vishnu’s consort, the Goddess of Wealth; Saraswati, Brahma’s consort, is Goddess of Art and Knowledge; Durga ( “the invincible”) is a manifestation of Parvati, consort of Shiva, Goddess of love, fertility and devotion. Parvati’s older sister is the powerful goddess Ganges and mother of the much loved Ganesh. And on and on, there are 167 goddesses listed online most of them variations of the same principles.

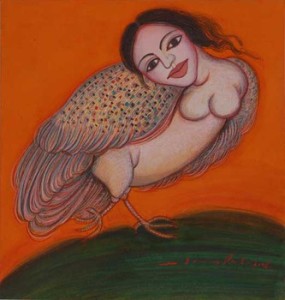

Gogi’s work has long been about the female spirit. She transforms ancient figures into contemporary forms. Rather than the obvious goddesses (although she has depicted Kali Goddess of Time, Change and Destruction), her work includes obscure mythical creatures based on early Sanskrit texts including the Kinnari ( (part bird, part female), nayika ( heroine) Kamdhenu, (wish fulfilling cow), burraq (dancing horse/human), hatha yogini ( firm, unyielding female yoga practioner). She has transformed these creatures and characters in her own way to express female power, resilience, and the contradictions of contemporary Indian society.

The only other specific historic person she has represented is Nati Binodini, a 19th century stage actress who defied conventional society, to pursue her career.

Born in Neoli, Uttar Pradesh, in the foothills of the Himalayas, where her father was a freedom fighter, Gogi also comes from a family who defied conventions. Her grandmother was the first woman to take a professional job in Lahore in the beginning of the twentieth century. She was also a pioneer in removing her outer heavy veil, leading to accusations that she was “naked”.

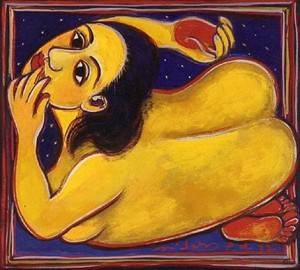

Gogi defiantly depicts all of her women as sensuous nudes who are also powerful and independent. Their big eyes examine us, challenging us to interfere with them. Sometimes they take on impossible yoga positions, or fly through the sky. Their sensuality is not only the result of their luxuriant shapes, but also the stunning, highly saturated colors the artist adopts. Still, as one art historian points out, Gogi was going against the flow of feminism as she pursued her commentary on women through naked bodies. It is partly the result of her grandmother’s act of defiance in removing the veil. Partly, the fact of the contradiction that women’s power according to societal norms, must be hidden from men behind coverings, and therefore it becomes a means of oppression.

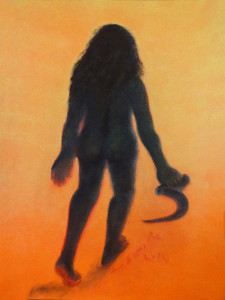

The new work for a young woman who wanted to fly through the sky, but was cut down from her dreams by a ruthless, ignorant act of violence includes a sickle, in several versions. A sickle is a traditional means of cutting, a reference here to the violence of destruction, as well as an attribute of power in the hands of Kali. In one painting, a silhouetted dark ghost of a powerful female strides away from us: grasps the sickle herself. This young woman sought to create change in society like Kali, the Destroyer of Time and Death. The painting suggests a space beyond our world. Unique in Gogi’s work we do not see her face, or her body, only a shadow.

Nirbhaya’s death as a sacrifice to social forces beyond her control, also looks back to the tradition of sati, the sacrifice of a woman on the funeral pyre of her husband, or even father, something Gogi has also represented.

But Gogi is honoring Nirbhaya, her hopes and dreams, even as she gives us the image of blood spattering over an empty rectangle, an empty life.

The ongoing violence against women in all parts of the world becomes part of the content of this group of paintings, as Gogi deeply understands both the history of powerful women and their vulnerable position in a changing world.

This entry was posted on January 27, 2015 and is filed under Contemporary Art, Contemporary Art In India, Feminism, Uncategorized, Women Artists.

American Art at the Newly Expanded Tacoma Art Museum

Tacoma Art Museum with detail of Marie Watt, Blanket Stories: Transportation Object, Generous Ones, Trek 2014, Cast bronze.

THE AMERICAN WEST: THE HAUB FAMILY COLLECTION AT THE TACOMA ART MUSEUM

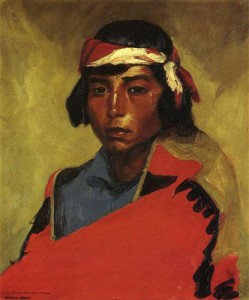

Elk Buffalo, The Monarch of the Plains created in 1900 by Henry Merwin Shrady sets the tone for the exhibition in the new wing of the Tacoma Art Museum, designed by Olson Kundig Architects. Shrady drew his buffalo in a zoo. This monarch of the plains, like so many of the Native leaders depicted in these paintings at this time, was captured and confined.

The mighty buffalo is a frequent subject in the Tacoma Art Museum’s new collection of 295 works of American art by 140 artists acquired by a generous donation from the Haub Family. In a later gallery, we are confronted by the fauve-inspired Buffalo at Sunset by Apache-affiliated artist John Nieto painted in 1996. In between is Frederic Remington’s Conjuring Back the Buffalo of 1889, filled with skulls, which marks the condition of the buffalo at the end of the 19th century: almost extinct as a result of widespread and intentional slaughter.

The effort to exterminate the buffalo failed. They are now not exactly thriving, but numerous. Native peoples also survived attempts to exterminate and assimilate them and to terminate their tribes. Today many aspects of their cultures are being resurrected and reshaped in dialog with the contemporary world. More than that though, as profound speakers and savvy activists, they play a crucial part in contemporary efforts to stop the devastating practices causing climate change.

At the far end of the sculpture gallery (its plentiful natural light carefully controlled by the architects), a conversation begins. Beside a 1978 bronze sculpture of Chief Washakie by Harry Jackson, the words of the Chief spoken exactly one hundred years earlier eloquently state the physical restraints of those years:

“The white man, who possesses this whole vast country from sea to sea, who roams over it at pleasure, and lives where he likes, cannot know the cramp we feel in this little spot…every foot of what you proudly call America, not very long ago belonged to the red man.” —Chief Washakie, 1878

By including this stirring description by Chief Washakie of the nightmares of forced resettlement, Tacoma Art Museum Haub Fellow, Asia Tail, begins the task of reframing the romanticized concepts of the art of the West on display in the Haub Collection. Affiliated with the Cherokee tribe, Tail explained, “The quotations are just the beginning of a project to integrate Native voice and presence in this exhibition.” Four compact interior galleries display a selection of 120 paintings from the Haug collection. The understated design reflects Olson Kundig Architects’ surprising philosophy that art, not the architecture, should dominate at an art museum. The new wing is meant to evoke both a railroad boxcar and a longhouse, two references to the West embedded in Tacoma.

Comments by both Haub Curator of Western American Art Laura F. Fry and native speakers appear beside many of the paintings and sculpture throughout the exhibition.

For Junius Brutus Stearns’s The Meeting of Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison at Vincennes, 1851, Laura Fry focuses on the artist’s love of ancient history: “In creating this fanciful image some 40 years after the Shawnee leader’s confrontation with General William Henry Harrison in 1810, Stearns presented the scene of an American conflict between two epic leaders in the same light as the legendary events of ancient Rome.”

But we also hear from Tecumseh himself “The only way to check and to stop this evil, is for all the red men to unite in claiming a common and equal right to the land. … The white people have no right to take the land from the Indians, because they had it first; it is theirs.”

Wanata (The Charger) Grand Chief of the Cherokee by Charles Bird King purposefully, but with somewhat pathetic results, tries to give Wanata the pose of European “grand manner” portraits. The artist never met Wanata, so he made up the portrait from someone else’s sketch. King was commissioned to paint portraits of the Native leaders who came as delegates to negotiate with the US government in 1821. The idea of a vanishing race was already creating Indian galleries on the East Coast in the 1820s.

Next to Canonicus and the Governor of Plymouth by Albertus del Orient Browere, Tail comments “This painting hints at the long history of conflict between Native American tribes and the US government. Native leaders have continued to fight, long after Canonicus’s time, to protect their people and advocate for their rights. Because of the efforts of our ancestors, millions of Native Americans from hundreds of nations are still here today.” Obviously this is a direct refutation of the prevailing ideology behind the paintings of native leaders in the 19th century, that they were a vanishing race.”

Scott Manning Stevens (Director of Native American Studies at Syracuse University) points out in his catalog essay that including the Northwest in the concept of the West integrates the hundreds of native groups practicing various ways of life. It moves beyond the limited cliché framed by Western movies that focus on cowboys and Indians of the High Plains. The catalog also includes insightful essays by Fry and Peter Hassrick (Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming) as well as color illustrations and discussion of individual artworks.

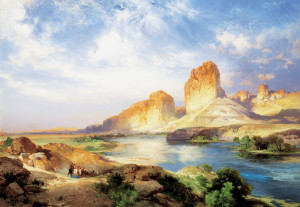

The collection includes many surprises (most of the works have never been exhibited before), including a work by Rosa Bonheur, and paintings by Robert Henri, Thomas Hart Benton, Maynard Dixon, and Taos school artists, as well as examples of landscape painting by such well-known artists as Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran.

Some people I spoke with felt strongly that the museum should work much harder to deconstruct the clichés of the West in the labels and in the organization of the display. I would have liked to see more contemporary native art.

Curator Laura Fry understands the issues. She spoke of complicating given ideas citing, as an example, the multiple racial backgrounds of cowboys. Asia Tail’s project represents an ongoing commitment on the part of the museum to expand native voices.

The museum also commissioned a public sculpture outside the new wing by Seneca artist Marie Watt: Blanket Stories, Transportation Object, Generous Ones and Trek. The artist invited community members to contribute blankets that would be cast in bronze at the Walla Walla Foundry. Each donated blanket has a story that can be accessed on the museum website. It creates a giant relaxed x shape in front of the museum, a concept that could have many meanings.

Clearly, the museum is interested in framing the collection of art of the American West in new discourses. I look forward to hearing about further programming that will introduce new ideas and voices to counter the traditional romantic perspectives in art of the Haub Collection.

This entry was posted on January 16, 2015 and is filed under American Art, art criticism, Western Art.

City Dwellers: Contemporary Art from India at the Seattle Art Museum

Debanjan Roy,India Shining V 2008, fiberglass with automotive paint, 66 x 32 x 36”, Collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan. ©Debanjan Roy, Photo courtesy Aicon Gallery.

GANDHI WITH AN IPOD!

A life size red fiberglass figure of Gandhi painted with glitzy red automobile paint and holding an iPod leaps out at us in the first gallery of “City Dwellers, Contemporary Art From India,” works on generous loan to the Seattle Art Museum from the collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan.

Debanjan Roy’s sculpture defiantly alters our image of the humble white-garbed Gandhi. We are a long way from the non-violent Gandhi, who was murdered in January 1948 in the aftermath of the extreme violence of the Partition of India and Pakistan. (See the film Earth by Deepa Metha for a potent telling of that time). The red color of this sculpture refers to that violence; the shiny synthetic material refers to the contemporary reality of India, commercial, business oriented, and materialistic: the antithesis of everything that Gandhi believed in and lived.

Scooter, 2007, Valay Shende, Indian, b. 1980, welded metal buttons, 45 x 70 x 30 in., Collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan. © Valay Shende

Valay Shende’s gold studded motorscooter is a magnificent statement that belongs also in the concurrent Pop Art exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum. It is popular culture glorified with gold. Shimmering, tactile, and seductive in its generous curves, we can visually immerse ourselves in this scooter with its mixture of the modern and the contemporary.

All of the work in this exciting exhibition plays with the past and present, upsets clichés and fixed romantic notions of India, and provides insights into where this huge and dynamic country is today. At the same time, it is clear that all of these artists have great reverence for their own history, both cultural and historical. I can’t help envy contemporary artists in India for the enormous wealth of cultural references at their disposal.

Reassurance, from the Definitive Reincarnate series, 2006, Nandini Valli Muthiah, Indian, b. 1976, color photograph, 40 1/4 x 40 x 1 in., Collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan. © Nandini Valli Muthiah

Disillusioned, from the Definitive Reincarnate series, 2003, Nandini Valli Muthiah, Indian, b. 1976, color photograph, 40 1/4 x 40 x 1 in., Collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini

Nandini Valli Muthiah places the blue-skinned Krishna in contemporary surroundings. In contemporary India, Krishna frequently appears in full size statues and reenactments in religious processions. Here we see him up close and brooding. We can see the intricate details of his costume, the painted blue of his skin, and a glimpse of his inner life. The juxtaposition of myth and reality is deeply moving. Muthiah conveys the burden and responsibility and perhaps the inspiration of renacting Krishna in these unusual photographs.

Include Me Out II, 2011, Vivek Vilasini, Indian, b. 1964, inkjet photographic print, 68 1/4 x 64 1/4 x 2 in., Collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan. © Vivek Vilasini

Vivek Vilasini photographed dozens of people seemingly standing on an historical façade of a Hindu temple in South India. If we look closely we see a catalog of contemporary Indian people from school children in uniforms to women in saris. The artist himself sits near the top in contemporary dress. Vilasini seems to have been able to pose all of these people in such a way that we are convinced they are actually standing on the narrow ledges of the temple where the gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon have cavorted for centuries. Goodbye Hindu gods, hello contemporary India

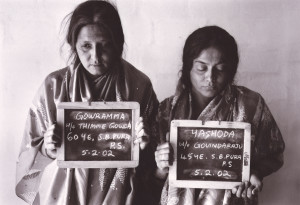

Criminals (after 2001 newspaper photograph), from the project Native Women of South India: Manners and Customs, 2000-2004, Pushpamala N., Indian, b. 1956 with Clare Arni, British, b. 1962, C-print, 15 x 22 in., Collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan. © Pushpamala N., Photo courtesy Nature Morte, New Delhi

Pushpamala N and Clare Arni perform and restage publicly available imagery from historical paintings to police mug shots and, of course, Bollywood posters. So effectively are they re-created that you always have to look twice to know that they are not the real thing. Their work is political: they are looking at female clichés, oppresions, and assumptions by foreign photographers who romanticize India. Here is a provocative analysis of her work and other artists in the exhibition.

One of the most fascinating photographs in this series is the Tamil leader who is also a film star reenacted by the artist, based on a magazine cover. So we have several layers , and a deep reflection of politics and power as a performance both by Pushpamala N and by Jayalalitha, the film star who became a Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. She was recently arrested and is just out on bail this month.

Pushpamala N., ‘Cracking the Whip (after 1970s Tamil film still)’. From the photo-performance project Native Women of South India: Manners and Customs, 2000-2004. Type C-print on metallic paper, 20 x 24 inches. Collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan. © Pushpamala N.,

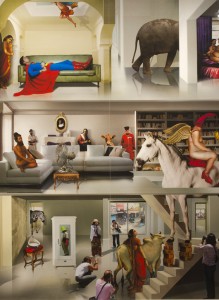

Manjunath Kamath’s amazing triptych, of which we have only the center panel here, has a dizzying array of references. Looking at it is a treasure hunt to see what we can spot. But before descending into the details the overall coherence of the piece dominates, the artist plays with perspective space in a way that corresponds to the compicated spaces of sophisticated Mughal painting that show interiors and exteriors, gardens and landscape, near and far all at once.

I can easily spot some of the cultural references: Superman, and Picasso, and tourists taking pictures. But there are other references I would like to know more about. I particularly love the juxtaposition behind the sofa of Christ, the bull and the red uniformed Chelsea Pensioner ( identified immediately by my British born husband).

Overdose, 2009, Manjunath Kamath, Indian, b. 1972, color photograph, middle panel: 95 1/2 x 72 x 2 3/4 in (one of three) Collection of Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan. © Manjunath Kamath

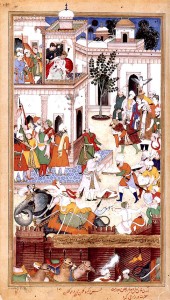

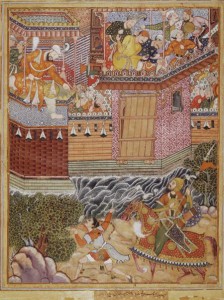

Hamza outside the Fortress of Armanus, 1567-82, Mir Sayyid ‘ali, Persian, active 16th c., opaque watercolor, ink and gold on paper, 34 15/16 x 28 3/4in. (88.8 x 73cm), Seattle Art Museum, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Richard E. Fuller, 68.160

MUGHAL PAINTING POWER AND PIETY Asian Art Museum July 19 – December 7, 2014. The dazzling exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum is paired with Mughal Painting: Power and Piety at the Asian Art Museum, a small, but intense selection of miniature paintings along with objects similar to those that appear in the paintings, such as daggers, rings, and necklaces. This dialog of two and three dimensions is provocative, and helps us to look much harder at the tiny details of the miniatures (magnifying glasses are provided). Mughal painting initially was the result of the amazing rule (1556-1605) of the enlightened leader Akbar who unified India. He embraced Persian cultural traditions, as well as reaching out to include all religions, created a huge library with books in many languages, and brought artists, scholars, translators and holy men to his court.

Although he was a Muslim, he sought unity among different traditions. Akbar altered the course of Indian history and art in a way that lasted many centuries. In a brilliant lecture at the Asian Art Museum by LACMA associate curator of Islamic Art Keelan Overton ( who also curated the exhibition which will be followed by a second installment on Decmber 9) , we learned the ways in which these miniatures were put together in albums for the pleasure of the elite. Once you start looking, you can seem seems and additions, glued together just the way we make albums today.

Akbar’s ecumenical philosophy and Gandhi’s non violence have long vanished in India. Since Independence in 1947, sectarian violence has repeatedly erupted in India to devastating results, but today, the religion of capitalism is the dominant force and focus of disruption. These contemporary artists provide us with both critique and humor. A fiberglass Gandhi with an iPod? Krishna in a four star hotel room? Makes perfect sense.

This entry was posted on November 11, 2014 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, Contemporary Art In India, Film, Performance Art, Photography, Picasso, Seattle Art Museum, Uncategorized.

The Common SENSE: Ann Hamilton at the Henry Art Gallery

“The common SENSE”

Ann Hamilton at the Henry Art Gallery October 11, 2014 – April 26, 2015

I like the multiple puns in the title of this exhibition. Common sense is a term we use for what works on the most basic level. It helps us through a lot of situations that might otherwise be difficult. (We should, in fact, think of it more often these days, when everything seems so convoluted). Another meaning is suggested by capitalizing SENSE. Ann Hamilton is fascinated by our senses: this exhibition emphasizes the sense of touch, but seeing and hearing are part of that idea for Hamilton.

A third meaning is that everything on the planet shares the common sense of touch. According to Jainism, the world is divided by the number of senses we have. The only sense that every class of life on the planet has is touch, some have only that (the pay off is that some one-sensed vegetable bodies, like the turnip, have numerous souls). One might say that touch is what we will be left with when all else fails.

That idea suggests another reference (not a pun) in this title. Commonsense is telling us that climate change is deeply altering life on the planet. Common sense says we must change.

The exhibition leads us to this idea in an unusual way.

In each gallery a shelf has been set up with pairs of metal prongs that hold stacks of a single passage of text on newsprint. We could read, and, if we chose, and even take a text with us. During the course of the exhibition, then, the texts will disappear (they are taken from a tumblr site where we can all add passages that are selected for inclusion). Some new texts will be added, but even in my two visits separated by ten days, there were many gaps where texts had been before. Gaps, that is another point here.