West of the Caspian Sea “Love Me Love Me Not” Azerbaijan in Venice

On the West side of the Caspian Sea, in Azerbaijan, Baku is the showpiece of contemporary life in the country. “Love Me, Love Me Not, Contemporary Art from Azerbaijan and its Neighbors” was commissioned by Yarat, a contemporary art space in Baku that sponsors extensive exhibitions and programming. Yarat is led by the youthful and talented Aida Mahmudova.

Baku has been a prosperous oil city since the early 19th century and that oil was a prize much sought after by both Stalin and Hitler during World War Il, and by superpowers ever since. A massive pipeline was completed in 2005 carrying oil from Baku through Georgia to the Turkish port of Ceyhan. The pipeline was of course loaded with international power politics. It couldn’t go through Iran because the US said no, it couldn’t go through Armenia because of long standing tensions, so it had to go UPHILL through Georgia. Revenues from the pipeline have been enormous as has the impact on local ecologies and communities as presented in Ursula Biemann’s video Black Sea Files.

The area around Baku is literally soaked in oil and has been for many decades. Some of the local people see the oil as healing or sacred ( in the spirit of Zoroastrianism water and fire are sources of ritual purity). The reality is that the area is full of toxic wastes.

Some of the huge oil revenues have found their way into support for contemporary culture. The seventeen artists in “Love Me, Love Me Not,” primarily come from Iran and Azerbaijan, but also from Georgia (Iliko Zautashvili) and Turkey (Kutluğ Ataman). Iran has more Azeris than Azerbaijan, but Azerbaijan and Iran are also long time rivals, so their coming together in Venice is significant.

Dina Nasser-Khadavi, a curator originally from Iran, declares that this region is not part of the so-called “Middle East.” It is also not simply Trans Caucasian. Azerbaijan and its neighbors have a common history as part of the Ottoman, Persian and Russian empires.

Nasser-Khadavi declares “this show does not take a political stand, nor is it aimed at making a statement.” Obviously this is one of those disclaimers that assumes that politics can be removed from the art and the exhibition just by saying so. But the statement itself also reflects the close connections between the government and support of contemporary culture. Obviously,criticism of the government is not going to happen in this exhibition.

The exhibition is intended to enable Euro centric viewers to correct their ignorance about this region, an ignorance based on,among other factors, media-generated stereotypes. Media simplifications are referred to in Nasser-Khadavi’s essay with the example of Ben Affleck’s film Argo.about the 1979 Iran hostage crisis. Media information is a deliberate political campaign, so countering it with complexity, as this exhibition strives to do, is clearly a political act. Under the guise of aesthetics, the works shown here subvert clichés.

The title of the pavilion, aside from reference to the familiar children’s game, was adapted from a work by the group Slavs and Tartars, Love Me, Love Me Not/ Changed Names, 2010, which refers to the changing names of cities in the region. As they articulately state, “[it] celebrates the mulitilingual, carnivalesque complexity readily eclipsed today by nationalist struggles for simplicity and permanence.”

Indeed the complexity of language in this region is mind boggling.

As this region changed imperial affiliations over the course of a century, the written script changed as well, from Arabic, to Latinized Turkish, to Cyrillic and now Latin. Various former Soviet republics have followed different paths following independence from the Soviet Union. In Azerbaijan, speaking Russian is still considered a mark of the elite but written Azeri is Latinized Turkic, with its vocabulary, grammar and structure based in ancient Turkic , a different language branch than the modern Turkish of Turkey.

Lost in Translation… This Too Shall Pass, is a projection piece by Rashad Alakbarov in which words written in all of these scripts dangle from the ceiling in mobiles that turn in response to the air and

appear and disappear according their relationship to the light source.

Mahmoud Bakhshi’s Mother of Nation, directly refers to oil and its mixed role as source of wealth and source of destruction, in a sculpture that resembles a ziggurat built of gold blocks. At the top is a baby pacifier. This sardonic reference by an Iranian living outside of Iran, certainly has several layers of meaning.

The Tree of Wishes by Rashad Babyev refers to consumerism as much as ritual by its use of designer silk scarves instead of the rags of traditional wishing trees.

Ali Hasanov’s Masters, is a pile of traditional brooms made of bundled twigs, traditionally used for cleaning, now discarded, become a reference to the role of simple functions performed by ordinary people that are being ignored.

On a similar theme, the well known Kutluğ Ataman provided a section of his large scale multimedia installation, Mesopotamian Dramaturgies. Here it features a column of forty two television sets with close ups of dozens of villagers from Eastern Anatolia, all silently standing against a wall of old stone or concrete. The wall is the only signifier of where these people are living, but their silent gaze looks back at us, forcing us to see them as individuals. They are the people on the ground, affected by larger geopolitical forces ( also addressed in Ursula Biemann’s work)

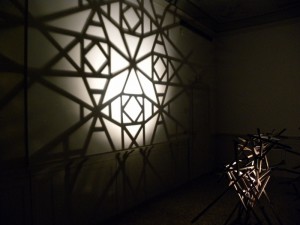

Farid Rasulov’s creates traditional stained glass designs embedded in chunks of concrete to address the juxtaposition of the traditional and the contemporary.( see also image at top of post). It is a direct reference to the city of Baku, which juxtaposes brutal modern and post modern skyscrapers with preservation of historic sections. The historic buildings in Baku become a type of fantasy of the past, accessible for tourism like a Disneyland, in the midst of the skyscrapers.

Orkhan Huseynov collects interviews from his peer group about “Bruce Lye”‘s films. The films imported to Azerbaijan were actually imitations, by an impersonator, Bruce Lee, who was imitating Bruce Li. The entire sequence plays with the idea of authenticity, fantasy, and shared cultural experiences. We sit in period furniture as we look at the videos of these young men recalling what the films meant to them, now knowing it was all an imitation.

Fashad Moshiri creates carpets with reproductions of the covers of contemporary fashion, film, and gossip magazines, also a reflection of the cultural moment. In his case, he is crossing between the lowest common denominator of magazines, and the high art of silk carpet weaving. Here he creates a “kiosk” of hundreds of carpet/magazines, also playing with idea of consumerism, media stereotypes, and tradition.

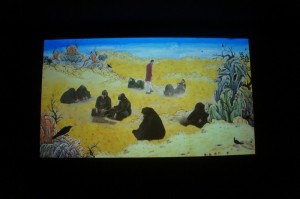

“King of Black” by Shoja Azari brings together poetry, film and miniature painting. The story follows from one section of

“Haft Paykar” (Seven Beauties) a twelfth century poem by the Azerbaijani Poet Nizami. the mythic story follows the King of Black as he searches for the reason a city is in constant mourning. It extols the virtue of patience. The animation is lush: the star walks through the elaborate landscapes of miniature painting.

Azari is Iranian, but as her name indicates she is ethnically Azari. The metaphor she has chosen may be a subtle reference to the Northern Iran area separated from its Azari roots.

All the artwork addresses various traditional cultural practices, overlaid with pointed references to the contemporary world. The question of the role of “craft” traditions in contemporary Azerbaijan permeated many of the works.

The celebration and reinvention of traditional craft is central to works like Recycled by Aida Mahmudova, which reuses ornamental window grates, or Afruz Amighi’s woven plastic and plexiglass with motifs from traditional Venetian glass and Islamic brass (on the left of the image above). Faig Ahmed takes off from carpet weaving to create an abstract design in thread.

Similar concerns appear in the official Azerbaijan pavilion

“Ornamentation,” which includes two of the same artists, Rashad Alakbarov and Farid Rasulov whose imitation carpet pattern work opens the installation(above)

The pavilion is sponsored by the Hedar Aliyev Foundation in Azerbaijan, the Foundation of the wife of the President. It simply celebrates the fact that the “history of the country is encrypted in its carpets, stone sculpture and embroidery.” The statement mentions the interweaving of “Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and ancient art traditions.” (and Islamic?) and suggests that these motifs are the real alphabet of Azerbaijan as contemporary artists draw on them to create contemporary conceptual art.

“Ornamentation” emphasizes the rich craft traditions of Azerbaijan and nearby areas, traditions that have passed through many changes and date back many centuries ( way before all of those empires). Crafts were banned during the Soviet era as bourgeois. Now they are co- opted for nationalism and tourism. But those deeply held traditions are also a rich source for this provocative group of contemporary artists.

It is a straightforward idea that is easy to understand in the rush of Venice Biennial pavilions. But the visual and intellectual impact of the pavilion, compared to “Love Me Love Me Not”, is more haphazard.

Alakbarov’s wonderful sculpture stands out: it becomes a readable pattern on the wall when a light is shined through it at just the right angle. It is an immediately understandable work, giving us the insight of the fugitive nature of material reality.

The Yarat pavilion goes further, not only geographically, but also conceptually, arguing for layers of meaning that include hybridity, nostalgia, memory, and the role of culture in general. As regards the geographical concept, I have not discussed the Russian and Georgian artists here, who touch on these themes as well.

But one of the wonderful aspects of the Venice Biennale is that a region that is so distant geographically from Europe and the US is brought up close for us to think about and reflect on. It is fortunate that the government of Baku and its urban elites have the wealth, intellect, and inclination to support contemporary culture.

From that patronage, we cannot expect to see art about the dark underbelly of Azerbaijan, but these exhibitions present some intriguing artists, as well as information about a major center of contemporary art in Baku.

This entry was posted on December 10, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Venice, Venice Biennale.

HONORING ANTHONY CARO 1924-2013

I saw Anthony Caro’s exhibition at the Museo Correr on the Piazza San Marco in Venice on September 29 and he died on October 24 in London, so this exhibition is one of the last for which he supervised the installation (which he did with great precision.See the video of Caro installing his work at the Tate Gallery in London and talking about it.)

Caro, for me, is a reminder of my roots, my early career, as a believer in the idea that abstraction is an end in itself; that it is full of utopian meaning.

Caro was creating expressionist clay works under the influence of Henry Moore, although reacting against his smooth surfaces, when he came in contact with David Smith and Clement Greenberg in the early 1960s and entirely changed his vocabulary to abstract metal planes painted in bright colors, like Early One Morning from 1962.

Clement Greenberg’s ideas dominated my graduate studies in contemporary art in the early 1970s. I completely believed in Caro’s spare metal planes and space filling pieces as meaningful cerebral aesthetic statements .

Having giving little new thought to Caro during my many years of teaching, I was shocked when, in 1999, I saw his Last Judgment in Venice. It changed my perspective on Caro entirely. It was the antithesis of everything I thought I knew about him. Content heavy, mixed materials, full of the horrors of war. The material is a combination of stoneware, steel, cement, ceramic bronze, brass. It was spiritual, rather than religious, iconographically still abstract.

Now this spare exhibition in Venice. Nothing distracts from immersion in space and material. There is no explanation of metaphor, context, or significance. I am back to the early ideas of form in and of itself, and, surprisingly, because he is a consummate sculptor, he rivets me.

I know from his Last Judgement that Caro has many layers.

When you look for metaphors or meaning on his website, you will not find them: all the work is organized by materials and size. So I will simply give you some images and brief ideas here. There is a strong classical, expressionist, spiritual dimension in these abstract works.

It seems his own choice is to primarily give people an experience that is outside of time and place as in the Venetian exhibition. It is a utopian experience, we become absorbed entirely in the work, the use of industrial materials that create different textures, weights, directions, often overcoming gravity to float in the air. These issues become the only thing in the world. It is odd to go back to thinking this way and feel at the same time a strange sense of euphoria, as I realize that each sculpture is many sculptures, according to where you stand, that each sculpture is actually shaping our experiences, freeing us to think outside the here and now, into some sort of perfect world, where people don’t kill each other. Here is River Song above and below at two different angles.

At the Museo Correr, Caro sculpts space with his work. His work does not simply exist in space, it defines space. The early drawings show us his roots in Cubism, and specifically Picasso, pulled apart. He sees figures in space as strong straight lines.

The exhibition touches on every decade of the artist’s career. Hopscotch 1962 of corrugated aluminum, jumps up in steps like a pick up sticks game, rising against gravity. Red Splash, 1966 is one deep red color, 4 tubes and a mesh, also during this 1960s period when he was definitively moving away from Henry Moore’s bronze solids and toward open floating planes, under the inspiration of David Smith.

Garland 1970 is green curved steel creating a landscape.

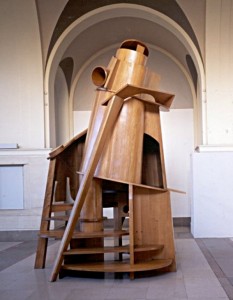

Child’s Tower Room of 1983 – 84 has a different quality, perhaps because it is made of wood, actually a special wood, Japanese oak. It has more solids, a spiral inside to a platform, but no one can actually go up, there is a discontinuous stair. It points to the future in a return to more solid forms.

Dejeuner sur L’Herbe 1989 is rusted steel reaching out from a horizontal plane, the appearance of casting, but found shapes, and subtle patina: no color. Caro can build up density without clutter, he multiplies forms to a point where we can’t take it in in one look.

In the Triumph of Caesar, 1987, waxed steel, the two sides go vertically up from the plane, creating an angle like a pediment

Suddenly at the center of the exhibition are subtle paper sculpture made in Obama Japan in 1981 with Washi tissue.

Duccio Variations 1990 2000 an obvious choice for Venice with its examination of Duccio’s space (this is one in a series)

And in the last room, Venetian, 2011-12, with red plexiglass. It glows with the red of Venice and changes radically according to the light, as does the city itself. As my friend Pamela Allara said, she felt her eyes had been cleansed by the end of the show. I felt my brain had been cleansed as well and only my eyes remained.

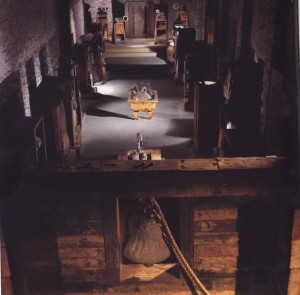

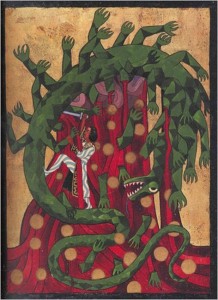

The Last Judgement is exactly the opposite, it is heavy, weighted with the cares of humanity, its sins and suffering. The installation has 25 separate “episodes” beginning with Dante’s boatman, Charon. It continues on the left with Without Mercy, Greed and Envy, Shades of Night, Prisoners, Hell is a City, Flesh, Civil War, Jacob’s Ladder. On the left side are Confessional, Unknown Soldier, Torture Box, Teiresias, Tribunal, Judas, Elysian Fields, Poison Chamber, Salome Dances, and The Furies In the middle is the Bell tower entrance, Door of Death, still life with skulls and sacrifice all culminating in the four last trump[et]s leading up to the final Gate of Heaven. The topics mix literary, classical, biblical, legal, and religious ideas.

The 1999 brochure accompanying the display links it to the artist’s disgust and horror with the “so called ‘ethnic’ cleansing in Bosnia, Rwanda and most recently with the worsening conflict in Kosovo. As a Jew he has been asked more than once to make a sculpture commemorating the Holocaust but has felt unable to undertake it as the subject is too terrible, too enormous to do justice to. However in 1992, working with the ceramicist Hans Spinner in the South of France, Caro made some ceramic pieces which resembled heads. When they were shipped back to his London studio they became the basis for his Trojan War sculptures, which were shown in the form a battlefield . . In a sense the sculpture is nothing less than Caro’s own Guernica . . . .It is fitting that with a century that began with the Gates of Hell of Auguste Rodin should now close with the Last Judgment of Anthony Caro. “

This material appears nowhere online. In researching Caro’s Last Judgment I only found one description linking it to World War II! Why is that? It is because these powerful, misshapen forms redefine all of his work: they bring together his deep sense of material and space with a specificity and direct sense of tragedy. Each sculpture is purposefully enclosed in a rectangular box, physically containing the tortured themes. The abstracted forms evoke direct associations with the history depicted. It is as though Caro, after a lifetime of efforts to create utopian spaces on earth, is now acknowledging here (as well as in his Trojan War series, )that what we have is the opposite.

The weighty catalog provides context, but no interpretation of the work itself: there is art history “’The Last Judgement’ in Western art, as well as essays “When Art Meets Politics by Nadine Gorimer, “Violence Between Individiuals Groups and States,” Robert Hinde, poetry by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, and potent quotations accompanying stunning close up photographs of the installation.

Perhaps the reason so little appears online is because the Last Judgement is in the collection of the Kunsthalle Wurth in Künzelsau, Germany, a small town near Heidelberg in Germany, that opened in 2001. From the website it is not clear if it is on permanent display, but the Wurth Museum co- sponsored the display in Venice with the British Council and the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation.

It was shown in the Antique Granary in the Giudecca, the spare industrial space enhancing the overall sense of horror of the individual pieces. Collectively, the pieces point toward The Gate of Heaven, as the climax of the path through the darkness of human actions. The Gate is an open door, as though it is enticing us to pass through, in spite of the sins behind us. But it is ambiguous if anyone is actually going to be admitted, there is no judge, there is no Saint Peter, there is no sense of salvation. Only an open door surrounded by sculptures that make reference to four trumpets that play at the resurrection

(one can’t help but think of Handel’s Messiah). So in the end Caro’s message is to offer the possiblitiy of salvation, just as his abstract nature based sculptures offer the possibility of utopia. The choice is ours which way we choose to go.

We have lost one of the greatest sculptors of the twentieth century.

This entry was posted on December 5, 2013 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, Contemporary Art, Modern Sculpture, Venice Biennale.

“A Mad Dash through the African Pavilions at the Venice Biennale” by Pamela Allara

I am thrilled to offer you today my first Guest Blogger

African Art Specialist Pamela Allara, Ph.D. with an overview of

the African Art Pavilions at the Venice Biennale

This year’s Venice Biennale was one of the best I have ever seen, and I have gone intermittently since 1964 when the U.S. pavilion, featuring Robert Rauschenberg , won the Golden Lion award. Since at least 1907, a major section of the highly-regarded survey of contemporary art has been exhibited in pavilions representing individual nations. With the exception of the U.S. pavilion, the nations were European, and the exhibition as a whole completely Eurocentric.

When at last in 2007 Simon Njami and Fernando Alvim introduced contemporary African art for the first time, the exhibition was unfortunately continent-wide, reinforcing the regrettable mind-set that Africa is a single country. On the upside, national African participation has grown since then, and this year, for the 55th Biennale–“Il Palazzo Enciclopedico” (June 1-November 24, 2013)–one could encounter diverse and sophisticated exhibits in five African national pavilions: Angola, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Zimbabwe and South Africa. Moreover, one of the first-time participants, Angola, won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation.

One strategy adopted by the Biennale’s Director, Massimiliano Gioni, was to create a series of exhibitions so vast as to demonstrate his central thesis that no one intellectual or spiritual system could possibly hope to encompass the vast diversity of the world in which we live. The result was that the visitor was required to run an art marathon, dashing through individual installations and pavilions that were various approaches to the encyclopedic theme, in a desperate attempt to take in as much as possible.

In the rush, I made a number of facile judgments, one of which was a negative assessment of the Angola’s “Luanda: Encyclopedic City,.” (see top of post). Housed in the splendiferous Palazzo Cini, normally closed to the public, the installation of stacks of photocopied street photographs by the young artist Edson Chagas created a marked contrast with the gorgeous, gold-framed Medieval and Renaissance paintings on the walls. Initially, the juxtaposition evoked the inevitable cliché the national pavilions in the Giardini had for so long reinforced: the extraordinary achievement of Western European culture vs. the pitiful backwardness of African society. In addition, I did not find the concept of purchasing the photographs for one Euro each especially original; and at least in the past the stacked papers in various exhibits by the Cuban-born artist Félix González-Torres (d. 1996) could be carried home for free.

However, after returning the States, I reconsidered my initial impressions of the decisions made by curators Paula Nascimento and Stefano Raboli Pansera. (Their interview on the Biennale website is well worth a visit here. Rather than a clichéd contrast between the ‘West’ and the ‘Third World’, one could consider the installation a demonstration of the entanglement of richer and poorer nations in the global capitalist system, with its vast dispersion of people and goods. In that context, it was fitting that viewers were invited to participate by parting with their own money. And kudos are due to the curators for selecting a young, relatively unknown artist for this first venture onto the Biennale’s international art stage.

In the photographs in Chagas’ Found Not Taken series (fig. 2), abandoned objects are repositioned within public spaces, encouraging the viewer to imagine potential narratives for the discards, while acknowledging that the potential stories of those objects could be endless.

Zimbabwe pavilion with drawing by VIrgina Chihota on the wall and two parts of an installation by Michaele Mathison called Landscape

As for the other pavilions, I will provide only a brief summary here: Zimbabwe avoided that nation’s harsh political realities by including in its very professional installation five outstanding artists whose concerns were primarily spiritual: Rashid Jogee, Portia Avavahera, Virginia Chihota (above, the drawing), Voti Theve, and Michele Mathison ( the installation).

Another first-time exhibitor, the Republic of the Ivory Coast, was also impressive. Curated by Yacouba Konaté, “Traces and Signs” led the viewer into its representation of this West African nation with the familiar but always delightful work of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, who was also included in the main exhibit in the Arsenale. However, this viewer’s ‘prize’ went to the sculptor Jems Robert Koto Bi, whose ambitious sculptures were so evocative of emigration and displacement.

A bit of context is needed before turning to Kenya. A secondary theme of the Biennale was the negation of its founding concept of art as expressive of a national culture, the concept enshrined in the Giardini’s national pavilions. In response to the globalism of contemporary art, France and Germany decided to switch venues, inducing immediate shock in the viewer. (France in the echt Fascist architecture of the German pavilion???) Moreover, Germany’s untitled exhibit in France’s pavilion contained only one German artist. South Africa’s Santu Mofokeng was included, with a strong selection of his haunting landscapes, as was Ai Wei Wei and Danita Singh. So, just as a handful of African countries were finally granted their own national pavilions, the exhibit as a whole was undercutting the very idea of nationhood.

Unfortunately, the Kenyan pavilion fell afoul of that internal contradiction. Perhaps in an attempt to appear forward-looking and sophisticated, the curators decided to jump on the ‘global’ bandwagon; in the exhibition, “Reflective Nature,” 8 out of the 11 artists were Chinese, and only two were Kenyan. With no context provided for the curious curatorial decisions, the exhibition was completely incoherent, generating much negative commentary on the internet. In Kenya’s defense, it is important to recognize that the idea of a national pavilion for non-western countries was a losing battle from the outset. The Giardini pavilions represent ‘the West’; set in back of the Arsenale or scattered around the city, the other, small, hard-to-find national pavilions were ‘the rest.’ It will be interesting to see what happens at the 56th Biennale.

Because my area of curating and writing is South African art, I will close with some brief observations about the exhibition, “Imaginary Fact: Contemporary South African Art and the Archive.” Initially, it was one of disappointment. As curated by Brenton Maart, it examined the trend in contemporary art to re-write history through re-presenting and reinterpreting existing archives. Obviously, this effort is especially pertinent to South Africa, where the examination of historical records, both written and material, is crucial to the process of creating new histories by unearthing overlooked or censored materials. The great variety of approaches found in the works of the 13 artists and one trio of collaborators from South Africa tended to dilute this concept, or at least suggest its increasing trivialization over time.

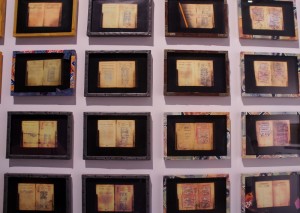

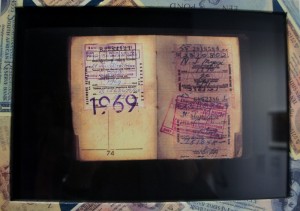

One of the first, and now iconic, archival investigations, is Sue Williamson’s For thirty years next to his heart, created in 1990, the year Mandela was released from prison, (fig. 4). With a grouping of 49 color laser prints, Williamson reproduces every page of Mr. John Ngesi’s dompass, the ‘dumb pass,’ required of non-whites for proof of residence, clearance for work, and taxes. Donated to the artist by Ngesi, it is now part of Williamson’s personal archive of apartheid, and it remains a powerful witness of the warping of identity by an oppressive bureaucracy,(fig. 4 a).

Around the corner from this riveting if familiar work was an installation by Joanne Bloch, currently a doctoral candidate at the Centre for Curating the Archive and The Archive and Public Culture Initiative at the University of Cape Town. (The curator is in the same program). In Hoard, (2012-13; fig. 5), the artist stocked a glass museum case with simulated rare objects such as the miniature gold Mapgunubwe scepter together with a recreated wooden block from her childhood; the juxtaposition attempted to “throw into question the categories of ‘real’ and ‘fake;…and take a stab at disturbing established or expected systems of classification.,” according to her artist statement. I found the installation obvious to the point of being facile, but to be fair, time constraints did cause me to rush to judgment.

If Bloch’s examination of the idea of the archive did not “allow the artist to create work with the potential to change the course of our contemporary world,” according to the curatorial essay, the contemporary archive created by documentary photographer Zanele Muholi indeed has demonstrated that potential. Her Faces and Phases series consists of black and white portraits of the LGBTI community in South Africa, and have been exhibited in major exhibitions globally. Installed salon-style along a narrow corridor, the viewer was confronted with individuals whom one could neither enumerate nor typecast. In that constricted space the viewer was denied a distanced gaze, and encouraged to feel a sense of solidarity with a group that has been “so far violently and blaringly erased,” in the artist’s words. Last year, Muholi’s flat was broken into and 20 hard drives containing over six years of work were stolen. But by now her very personal archive is sufficiently public—both in museums and online—that it cannot be erased.

Although the compressed space worked to Muholi’s advantage by briefly including the viewer in her community, it put much of the rest of the work at a disadvantage. One exception was the sculpture of Wim Botha, who was provided with a sort of mini-retrospective of work from 2009 to 2013.

One installation, humanoid figures constructed from books, and battling in mid-air, summed up the controversies over meaning that have characterized South Africa’s post-apartheid investigations of identities and histories. In an enlightened decision, the excellent catalogue has been made available for downloading from the exhibition website.

This cursory introduction will not be the last word on the African pavilions at the Biennale—at least I hope not. More time is needed to digest these exhibits. The Biennale itself was so sprawling that it has spawned ‘discussion groups’ in my greater Boston neighborhood where we share information, and hopefully, insights. That we would meet and debate in such post-exhibition sessions is indicative of something I can’t quite articulate: was this the Salon des Refusées of

- the 21st century?

This entry was posted on November 25, 2013 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Uncategorized, Venice, Venice Pavilion.

Sarah Sze “Triple Point” The US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

We could feel our expectations shifting as we approached the pavilion from the back, from the Czech pavilion, instead of front and center facing the traditional classical portico. We could see trails of stones on the ground and little piles of stones in alcoves and on ledges. Is this part of the exhibition?

It is clear that they are as soon as we reach the front of the pavilion, where the building looks as though it is under construction, and in a state of emergency: a high ladder with its steps covered with stones, pieces of wood, and plants, leads to a high platform, but the access to it is blocked by a two by four, supporting a stack of concrete blocks. Long aluminum struts reach into space and precariously construct another jerry-rigged support system that looked like it was about to collapse. Reaching up to the roof of the classical pavilion are more rods and on top what looks like a huge rock, barely balanced there. Looking closer there are more rocks at other points on the edge of the roof and stacks of what appear to be concrete paving stones.

This sense of impending collapse, or disaster, of jerry-rigged constructions, improvisation and making do is the perfect metaphor for where the US is today. Of course, no reviewers are touching that idea. They settle for enumeration of just a few of the dozens of found objects and materials that Sze uses in her installations. And it is an overwhelming exercise to name even a few of the hundreds of tiny things, both “found” ( I suspect not accumulated over time, but more like ready-mades from the store), and constructed.

Inside the pavilion the sense of disintegration continues. In every room, the artist began by drawing in black tape on the floor, the compass in marble that is set in marble in the entrance foyer of the pavilion. But instead of providing a sense of purposeful order, the compass is the basis for overwhelming complexity.

The title of the pavilion, Triple Point, is a term in thermodynamics that refers to a moment when, according to the exhibition brochure “all three phases of a substance (gas, liquid and solid) can exist in perfect equilibrium.” That sense of transformation of solid into air, of air into liquid, liquid into gas permeated the exhibition metaphorically, everything is in transition, is suspended in a state that is improbabe, optically inpenetrable,and mentally stimulating.

Rising above our heads in the first room is an outline in curved wood of part of a globe, cut across by a black metal geometric structure that evokes a staircase. There is also the sense of a burst of energy like an exploded tree with the branches reaching out (from a green center), attached to a fragment of a network (geodesic?). Below are fragments of pictures of landscapes arranged as though in an amphitheater. The structure is supported by various props including large empty cans of paint. It seemed like science fragmented, reminding me of one of those works of art of the 1960s, like Tingueley’s that were meant to be destroyed, but in this case there is no destruction, only a limbo of parts that are suspended in an improbable relationship to one another. There are interdependent in a profound, but fragile way, that is the same that can be said of human existence. Given the destruction of the planet currently underway, I could not help but see a reference to that here.

The next room was more intimate, like a laboratory with multiple stations, but this laboratory has holes in the tables; it is non functioning. Even as we look closely, we feel tricked by the spaces and voids. Black stones taped with blue are scattered around the edges of these strange work stations. Are they the future of life, are they the past of life? On some level, we know they are both and neither.

In the entrance foyer is a big rock sitting on that compass in the marble floor. But this, like all the large rocks in and on and above the pavilion, we now realize, is not a real rock. It is based on a photograph of a rock that has been projected onto a plastic material and wrapped around an aluminum armature (ecological Sze is not). The rock in the foyer is on a real compass, but our sense of order based on the compass is disrupted by unexpected obstacles that are not what they seem to be.

The next room is like an amphitheater in which objects are lined up like spectators; these spectators are the infinite array of Sze’s objects all sorted by size, color, material, to create what appears to be a rational order for the first time in the exhibition. But again, there is the sense of suspended animation, of something about to change, for these are the materials of her art, of our consumer culture, of our rubbish overrun planet, they are all going to be trash shortly, when the exhibition is over. But for this brief moment, they are arrayed, viewing the empty arena before them. (I can easily read it this way because when I was a child, my father used to array inanimate objects in parades through our New York City apartment).

Finally, there is the artist’s studio, in which she shows us her tricks, the rocks made from paper, wrapped around armatures, the collections of colored paper that stand in for nature.

The game of solid and transparent, of fiction and reality, fantasy and fact, is the theme of the exhibition. But I felt strongly that the real issue here was the breakdown of those barriers, the breakdown of the rational solution, the traditional belief system, the decomposing of reality, of expectations, of predictions into a triple point of ideas, objects and transparencies.

This entry was posted on November 18, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art of Democracy, Conceptual Art, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized, Venice, Venice Biennale.

English Magic

Jeremy Deller’s Pavilion for Great Britain at the Venice Biennale includes a lot of disparate elements, none of which the artist made. He does not paint, sculpt, photograph or draw. Rather he assembles objects and images (giving credit to those who make them).

By calling the pavilion “English Magic” he is off the hook on making a point, magic is of course sleight of hand, illusion, based on practice, but not substance. It is hard to tell what he is passionate about in this pavilion. He gives us several issues, but there is a Warholian detachment about the sum of the parts.

Andy Warhol was apparently a profound inspiration for Deller who mostly studied art history in school. Perhaps that is why he made a categorical statement that “good art shouldn’t try to do anything useful” to Emily Stokes of the Financial Times (Aug 2, 2013) and added, just to be sure we understood his position that “art gets co-opted by politicians to solve social problems.” These kinds of ideas would be the direct heritage of the modernist tradition of art history: its formalist emphasis for many decades (including those when he was studying), excluded social and political context from the meaning of the work. Fortunately that has entirely changed now.

Here are the various issues Deller presents, none of them necessarily related to one another, in the order in which we pass through them in the UK pavilion.

In the first room is a large banner photograph of a hen harrier hawk carrying a range rover in his talons, with a narrative that the rare hawk was purportedly shot by Prince Harry ( his car being carried off ?) and a friend on the Sandringham Estate in October 2007;

There are also a lot of neolithic arrowheads and axes actually displayed throughout the pavilion.

Opposite the hen harrier is a photographic mural and a narrative of a burning village representing the destruction by an angry crowd of an off shore tax shelter in the future (2017 easy to miss that) and banners of the structures for hiding wealth from tax collection.

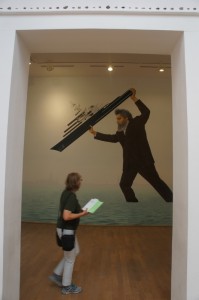

In the second room William Morris heaves the yacht of billionaire Russian Roman Abramovich into a lagoon in Venice in retribution for blocking the view in Venice in 2011 ; opposite are authentic William Morris fabrics and on a side wall is a collection of certificates of privatization in post USSR Russia.

So far so good, anticapitalism seems to be the theme.

In the third room are drawings invited from prisoners in the UK (who have committed crimes since returning from the Iraq war) of the Iraq war, as well as David Kelly who committed suicide because he questioned a weapons report on Saddam Hussein. This might be a subtle way of critiquing the government.

In the back garden is a tea room.

Next is a video that includes children playing on an inflatable Stonehenge,

stunning photographs of birds of prey, and the crushing of automobiles into junk.

The last room has a black and white photographic display of David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust tour of January 1972 paired with the youth of Northern Ireland being shot on Bloody Monday, the day after the tour began.

About half way through the video, I began to feel the pavilion lost its path. Here is why.

Deller loves public spectacle, both popular entertainment and demonstrations, protests and parades. In that sense he is a true Warhol descendent, he equally embraces public actions, musical performance, he even celebrates the Queen as a great performance artist. He is of the middle class that he presents.

Deller himself holds an anti-capitalist stance, he does not make art for sale, so works addressing the corruption of capitalism such as the abstract diagrams for “transfer pricing” for off shore tax shelters, would seem to be where his heart lies. He admires William Morris, who though he is known as a socialist , and opposed big government, was a middle class artist who loved medieval art and encouraged craftsmen and small businesses. Deller, like Morris, also cares about the corruption of government as in the lies around the Iraq war, and asking prisoners to draw pictures about it. Morris was interested in birds, and so, it seems is Deller, with the stunning footage of birds of prey included in his odd video.

Other writers declare that Deller is celebrating the good (tea drinking and David Bowie)and the bad (wars and tax shelters) of Great Britain.

For me the most fascinating moment of the exhibition was holding a “Neolithic ax”- see photo- and being told that this stone was not datable and therefore not valuable, while those on the walls of the pavilion were all authenticated and therefore priceless. The arbitrariness of the value of objects was obvious here, in front of the mural of a burning community that provides a tax shelter. That aspect of art, its absurd valuations, seems to be close to the artist’s heart. But he keeps his cards very close to his chest, and himself pursues a type of public performance persona as well (dressed in a type of British safari outfit in Venice for one critic.)

I, of course, always want to feel that artists are willing to take a stand, that they cannot afford not to, given their privileged position in society, their access to power, their role as court jester, their possibility for changing minds. Deller, on the other hand, wants to melt into the crowd, to be anonymous, to give equal time to public voices. Of course, while he is doing that, he is selecting what to present, and in this pavilion, he provides us with a particular cross section of Great Britain, history, music, birds, money, wars, and tea with just a small dose of the dark side of public protest (Bloody Monday) and royal privilege.

To one reviewer he commented that the Bowie fans and the people killed in Northern Ireland were all youth of the same age. But he didn’t take it further to analyze why some had the luxury to escape into music, and some died protesting their lack of civil rights. He didn’t seem to want to actually highlight the differences, they were all public spectacles. That type of non analytical thinking is, in the end, shallow. His inspiration for addressing popular culture and music and politics,

Warhol, pretended to be non analytical and deadpan, but in fact, his position was outsider and deeply felt.Warhol was of the working class, and therefore came to his imagery of stars and politics from a different, much less entitled, perspective.William Morris is the real mentor for Deller, also middle class, privileged, and idealistic, but scattered in many different directions. But Morris clearly had passion for what he believed in. Deller seems detached from the issues he presents.

This entry was posted on November 4, 2013 and is filed under art criticism, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.

Obsessions in Venice

Here is the logo for the Venice Biennale.

Small blue arrows going in and big yellow arrows going out of a brain represented by red and white concentric circles.

I can testify that this Biennial definately gave everyone a lot of penetrating arrows going in and out of our brains. We all know that artists are obsessive, but this exhibition showed that trait carried completely over the top, and with astonishing and mind stretching results.

Massimilano Gioni’s point of departure for Il Palazzo Encyclopedico/The Encyclopedic Palace, the vast central exhibition at the 2013 Venice Biennale, is his concern that the ability to imagine is threatened in today’s culture of digital media, instant news and communication.

His exhibition is named after the eponymous “Encyclopedic Palace of the World ” by Marino Auriti. While his structure was never built, Auriti imagined it as a place to order all the knowledge of the world in a single place. This is the type of megalomania and obsession that Gioni has located in the artists he selected to be shown in his own encyclopedia of the imagination. Most of the artists are working in the twentieth century.

Gioni is challenging contemporary artists and thinkers with the question: Is it still possible in the twenty first century to pursue this level of obsessive creativity?

An encyclopedia of knowledge stems from Diderot and the age of Enlightenment (also the age of colonization), when Europe thought it could organize the world better than it could organize itself:

“Indeed, the purpose of an encyclopedia is to collect knowledge disseminated around the globe; to set forth its general system to the men with whom we live, and transmit it to those who will come after us, so that the work of preceding centuries will not become useless to the centuries to come; and so that our offspring, becoming better instructed, will at the same time become more virtuous and happy, and that we should not die without having rendered a service to the human race in the future years to come.” —Diderot Vol. 5 (1755)

Such utopian paternalism is obsolete today (although political leaders and many others, are not necessarily aware of that). But Gioni has assembled hundreds of works by artists with encyclopedic bodies of work based on personal obsessions. He creates striking intersections between contemporary and historic art, famous and obscure, highly trained modernists and self-taught outsiders.

The artist, Rosella Biscotti, recorded the dreams of the women detained in a prison on Giudecca, evoked by this structure, dreams are the only means of escape for the inmates of this detention facility designed for life imprisonment.

Held in a psychiatric hospital for five decades, Arthur Bispo do Rosario created 800 tapestries, sculptures, and lavish ceremonial garments in prepartion for Judgement Day. Made from discarded materials in the hospital such as sheets and uniforms

The exhibition included art by the insane, the imprisoned, the displaced, the autistic, the deaf, the blind, people who exist outside of “normal” society, outside of the usual social structures, who are under great physical restraints. But all the artists, whether outsiders or not, had one common characteristic: they are obsessively possessed by images that they pour out in hundreds of drawings, sculptures, paintings, and journals.

These artists embrace vast amounts of knowledge ranging from the esoteric to the minutiae of science; they meditate on the supernatural, and try to depict their own hallucinations, to visually capture their own nightmares and dreams; they probe the microcosm, the inner workings of the body or the mind itself; they produce detailed observations about the natural world, or invent a new language. They explore memory, recover history or reinvent mythology. They create new cosmologies. They reimagine nature.

Is this not the definition of creativity: the act of moving outside the known, the easy, the predictable, the understood, to embrace another vision of the world?

Few artists survive into the historical record to be even acknowledged, much less respected. Yet, artists persist in believing in themselves by creating thousands of works of art, dozens of written pages. They construct their own reality as a way to order the universe in any way that they decide whether it is in room size installations or tiny journals kept for dozens of years.

From my perspective as a writer, I was most excited by systematically maintained journals that respond to intense writers like Jorge Luis Borges (Christiana Soulou), so intimate they are hard to reproduce,

and Franz Kafka (Jose Antonio Suárez Londoño)

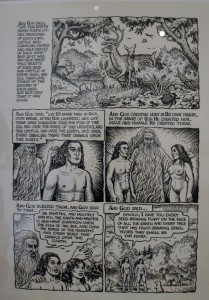

or even the Bible (Robert Crumb).

Carl Jung, obviously someone who actually succeeded in changing the way we think in a profound way, is the first artist in the main venue in the Giardini. His concept of the “collective unconscious,” the idea that all cultures share similar mythic impulses, is still an exciting idea. The fact that he spent years illustrating his own hallucinations as a means to reconnect to a mythic past that he felt had been lost in the twentieth century, demonstrates obsessive creative thinking as well as an unwavering faith in himself. His stunning watercolors, illustrations for his Red Book, filled a room with their glowing colors and eccentric imagery.

Now, you might ask, what does all this have to do with art and politics, the theme of my blog. Well, in my opinion, it is a political challenge to the dominant culture to celebrate imagination, to explore reordering what we know through dreams and hallucinations. As we are increasingly consumed by material goods in the here and now, as we are destroying the planet because the extractive industries cannot imagine an alternative, as we continue to wage war just like tribes and clans from centuries ago, as we continue to allow a few people to exploit the many, all of these calamities are the result of a lack of willingness to risk a more imaginative solution.

Imagination and creative thinking is threatening to the status quo. That is why music and art are considered frills to be eliminated from schools. Much better to have an ill informed public dosed into submission by the drug industry and fed shallow pieces of information. Rapidly disappearing are the obsessive outsider artists and home hobbyists of the past. Today we have instead, obsessive digital game players.

Enter the artists of the Venice Biennale as inspiring examples of artists who explore, think, read, record, and speculate about the world. That is a radical act in itself.

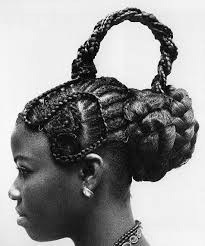

In the first Arsenale gallery the photographs of J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere fill the walls around the model of the Encyclopedic Palace at the center. Ojikere took 1000 photographs of the elaborate hairstyles of Nigerian women, of which only a fraction are on display here. These stunningly elaborate hair styles marked identity, social position, and cultural changes over 40 years starting in the late 1960s, an exuberant period of independence. So his project signifies a larger political reality, at the same time that it records timeless actions with significance rooted in tradition. Of course, it would have been more meaningful if each hairstyle had been explained in that context, rather than presented as simply a sequence of forms.

In the next gallery, the sculpture of Roberto Cuoghi stands as the dialectic opposite to the rationally constructed palace by Auriti: its bulging organic shape is unstable and incomprehensible. It was created not from stone but from a 3-D printer, and it suggests the collapse of lucidity and the world order as we know it; its bulk stretching into space as a strange new life form.

Such a dialectic appears repeatedly in the exhibition, the rational and irrational, the geometric and the amorphously organic.

Danh Vo’s installation combines references to an imposed religion (that is in itself irrational), and its rational artifacts, with irrational acts of cultural destruction. He has brought to Venice the wooden framework of a colonial church (from Hoang Ly, Thai Binh province Vietnam) that combines sturdy vertical columns inspired by European architecture with Vietnamese decorative elements.

The installation also includes evocative brown velvet wall hangings which formerly held icons and crosses, but now show only random darkened shapes, pentimenti, of those sacred objects.

A former icon crammed (we know not when or why) in a carnation milk box appears to be a torso of a saint, now become an inanimate but haunting piece of wood that yet speaks of its past identity. The objects and absence of objects hold the echoes of an imposed religion, a practiced religion, a past that has been destroyed, a lost culture that preceded both the recent past in Vietnam and colonization. But the whole is much more than the sum of its parts as we walk through the installation. We feel the whispers of old practices and the shouts of recent devastation in these quiet understated objects.

Repetition of infinite variation within a consistent format appears frequently in the Encyclopedic Palace. Yüksel Arslan, for example, creates all his drawings with paint made of blood, urine, egg whites, bone marrow, potash and honey, giving them a consistent brownish hue that belies the vast and complex details of his work.The homemade medium combined with the detailed exploration of the body compels us to look closely and plunge into his world. In the series here he outlines various mental and physical conditions such as cancer and schizophrenia,

creates a map of Europe out of crustacea and pays homage to John Cage, just for starters.

The esoteric and the spiritual was everywhere, starting with the theosophy movement in the late nineteenth and turn of the twentieth century. Of the artists who actually participated only a few were included – Hilda af Klimt and Rudolf Steiner for example. Steiner broke away to form his own Anthroposophy and af Klimt’s best work came when she liberated herself from the group (and Steiner’s) influence. In the early twentieth century such artists as Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian ( not included here) were crucial advocates.

Notably, theosophy combined Eastern and Western esoteric traditions and that thread of a European view of Eastern mysticism continues in Venice. The grand desire to re order and rethink cosmology is a popular obsession.

The European Surrealists with their embrace of the irrational, are an obvious reference point. The most striking example is the work by Ed Adkins using footage of Andre Breton’s collections that have now been dispersed. As we see the camera panning over an astonishing combination of modern art by fellow surrealists, African artifacts, and a fascinating collection of books, we feel we are looking directly into Breton’s mind. The only surrealist paintings in the Encyclopedic Palace are by Dorothea Tanning, perhaps because she died in 2012 and she is a link (with Max Ernst from the early 1940s) between early surrealists and later artists.

As a person who believes in assertive action in the public arena, I have trouble with mysticism and esoteric phenomenon. I have always tended to dismiss the entire sphere as trickery and delusion. On the other hand, the artists represented here have produced amazing art spurred by their esoteric beliefs, their synthesis of spiritual ideas.

Such a crucial historical figure as Rudolf Steiner

juxtaposed to contemporary artists like the dancer/movement artist Tino Seghal, here with very young Italian children mesmorized by his performance.

I was surprised to see my old friend, the ceramic artist Ron Nagle, included in this particular Encyclopedia. Nagle is a musician as well as a stunning artist. I have always admired his small geometric works in clay for their subtle color. The fact that here he is responding to his dreams is a real change of pace. But these works are still small, intense and subtle. Only now they are also unpredictable.

Ron Nagle

Another important aspect of the mind is memory and its physical manifestation, memorials; many works emphasized that including the huge mosaic 9-11 memorial by Jack Whitten.

There were dozens of other riveting artists. It is impossible to really review this show and do it justice. So lets return to the theme: can such obsessive creativity still happen in the 21st century?

A possible answer is posed by Ryan Trecartin. Difficult to watch, his videos (in collaboration with Lizzie Fitch) are based on the aesthetics of reality tv, sports, game shows and You Tube videos. Trecartin creates these works, their sets, their costumes, and he and his friends act in them, exaggerating their ghastly aesthetics as well as their sadism, the blend of reality and fantasy (we can no longer distinguish them). He nails the vacuity and cruelty of today’s online culture. It was frightening to see young children avidly watching them. But, undeniably, this work was crucial to the exhibition’s premise. Juxtaposed to the virtual retrospective of the giant of avant garde film, Stan Van der Beek, made the question of where are we going all the more evident.

Gioni displays the obsessions of artists to remake the world, to rethink spirituality, to order knowledge. He combines in a single overwhelming exhibition, the extent of artistic obsession and aspiration in a way I have never seen before. He celebrates the enormous output of artists who follow their creative passions.

Moving forward, with the obsolescence of all of the material culture from centuries of creativity, with books used as material for sculptures, rather than as documents of knowledge, where do we go from here?

I do not agree that imagination is threatened with extinction. Today, it is possible, even necessary, to imagine a new future. Even in the midst of our flood of consumerism, ossified political thinking, and innane digitized visual culture, many artists are doing just that. They are often also perceived as outsiders to the capitalist world, they are seniors, they are people of indigenous cultures, they are “dreamers”(term for undocumented youth brought to US as children). I would like to see those committed visual artists in the next Biennial. Like the artists from the last century, they too are taking on the world, they are taking on the tired belief systems of the past, and creating new synthesis, new ideas, or exposing the bankruptcy of old ones.

For examples you can read any of the other posts on my blog or my book Art and Politics Now, Cultural Activism in a Time of Crisis

This entry was posted on November 2, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art of Democracy, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized, Venice, Venice Biennale.

“Here is Where We Jump,” El Museo del Barrio’s La Bienal 2013

This astonishing work in El Museo de Barrio’s La Bienal 2013 “Here is Where We Jump” is described as follows:

“The black robe used in this work is called “the Knighthawk.” It is meant to be worn by the security officer within the hierarchy of the Ku Klux Klan. It was purchased online from an anonymous merchant in Upstate New York and then embroidered by a group of undocumented workers in Chinatown, New York. Chinatown is historically known as a neighborhood for counterfeit products as well as a place of employment for immigrants. The total number of stitches adds up to approximately half a million, a number that also represents the significant demographic of undocumented workers currently present in New York City.”

This cross-ethnic work by Ignacio Gonzàlez-Lang immediately provokes us. We see the KKK robe in a gallery focusing on young artists in the “post race” era and we think what is that doing here?? But with the additional information we know we are looking at an act of assuming power over fear. The other surprise is, of course, that we associate the KKK with oppression of African Americans in the South and this is a Museum connected to Spanish Harlem, but Gonzàlez-Lang extends its associations to make it a symbol of ignorant aggressive terror toward any “other.”

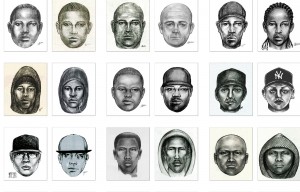

Gonzàlez-Lang’s Guess Who confronts us with our profound racism. The image here is a detail of a large group of police sketches, composite images based on public descriptions of people sought by the police for accused crimes. They are posted online and easily downloaded, which is what the artist did. He has grouped them to demonstrate how similar they can be.

The Bienal ‘s title is taken from one of Aesop’s fables, The Braggart, which challenges someone to jump: “jump here, jump now, here is where you jump.” In this context, it represents the act of a young artist jumping outside of the limitations of traditional art practice to try something radical – La Bienal seeks out emerging artists. The “jumping” theme here has a lot to do with process and experimentation with materials.

Where are we now with ethnicity? Only a few artists could be “labelled” immediately as Latino, as working with icons or topics or even materials that could be matched to the rich material traditions of Latino culture. The work of Alejandro Guzman stands out, with his vividly colored constructions of recycled materials. They are props for his performance art, but stand alone as sculpture (I would have liked to know more about the performance component).

Yes, it is color that seems to be almost missing from the exhibition, that visual feast of color that embraces us when we cross the border into Mexico and continue South. But there is also a strong history of modernism all over Latin America. We forget that what we characterize as “ethnic” is grounded in folk art traditions. Modernism as an elegant international style has been practiced all over Latin America by the educated elite for decades. That is the direction present in the subdued work of much of the exhibition. There are even several artists who are intentionally addressing US modernist abstraction, as in the works of G.T. (Giandomenico Tonatiuh) Pellizzi. In spite of his stunning name, he is painting fields of monochrome color on plywood that intentionally honors a work by Barnett Newman that was slashed some years ago.

Some of the artists address history: Christopher Rivera’s “Paradise is an Island and So is Hell” looks at imperialism by Theodore Roosevelt in Cuba. Aside from the vintage cartoons, the rest of the installation is experimenting with new materials; for example, implements that appear to be corroded. Are these the debris of capitalist invasions?

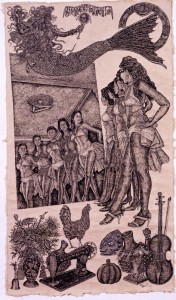

More traditional and straightforward, but impressive are the large ink drawings of Manuel Vega, which engage some familiar iconography of Latina art, although in an original way.

Another artist who taps into a folk art aesthetic, as well as street art are the brightly colored and pointedly explicit, paintings by Cuban born, self- taught artist Bernardo Navarro.

An entirely different type of work by another Cuban- born artist is by Pavel Acosta: he worked with scraps of paint in Havana, out of economic necessity, and because Havana is everywhere full of buildings with peeling paint. So we have a material that is a metaphor.

Acosta scraped the paint off the sheet rock wall in the gallery of the museum and used those scraps to replicate a painting in the museum’s permanent collection (see image below) as a line drawing (the lines are the negative spaces). His tour de force is a reflection of the extensive training that Cuban artists receive, they are technically and conceptually very sophisticated.

The painting in the permanent collection that he replicated by Manuel Macarulla, Goat Song #5: Tumult on George Washington Avenue, 1988 is a carnival scene in Santo Domingo. It indirectly refers to the role of the US in imperialist adventures in Santo Domingo and elsewhere in the title and the Washington Monument in the background ( which actually exists in Santo Domingo)

Accosto’s pale reflection removes the color and makes the subject hard to see, perhaps suggesting that the same shadowy operations are still going on, but more invisibly (or not? has it become only process?)

There is a partnership with artists from Brazil: Jonathan de Andrade uses video to tell us about disappearing history: the loss of Bolivia’s coastline to Chile in a war of the Pacific of 1879-84.

Paula Garcia presents two intriguing performances, in one she is covered in magnets as volunteers attach scrap metal until she looks like a strange monster; in the second, horses, hippos and monkeys emerge in surveillance footage of Oscar Niemeyer’s famous modernist pavilion. As the camera sweeps through the empty pavilion, the animals seem to be repossessing a lifeless space.

The dance performance by Sara Jimenez and Katilynn Redell is intentionally avoiding sexual and ethnic markers. Their movements inside the stretchy bright red fabric are visually stunning as the shape seems to ooze and stretch over a rock. Their work intersects with modern dance as well as modern art and performance art, but in exploring the hybrid body, they become actually the modern body with a few new possibilities.

Julia San Martin paintings evoke the feeling of terror from the period of the dictatorship in Chile through brief figurative references in a canvas that is a black and white semi abstraction. The mood of the work is nostalgic, terrified, and protective. One could say that the house motif is familiar, but here the reduced color and the scale bring the work off.

There are many other works in the Bienal: it is designed to encourage young artists, and in that goal we can see why the works sometimes have unrealized potential.

The tour de force video by damali abrams imitating self help shows presents us with the young artist for 365 days taking on a multitude of identities and issues. The problem is that we mainly notice she is really young and her topics are a lot about her appearance, clothes, and other trivial issues. Of course that is what self help shows are about , so she is drawing that large.

Another media action is Eric Ramos Guerrero Cortez Killer Cutz Radio The pirate radio station is taking off from Columbia University’s frequency in the middle of the night. I haven’t actually heard the broadcast, but any absconding with hegemonic communication seems like a good idea.

Finally there is Hector Arce-Espasas Welcome to Paradise. THis piece to me had that valuable quality, the synthesis of provocative materials and content. We see the unshapely vessels ( ceramic but they simulate silver pineapples) on a pile of crates. The assymetrical stack is unstable. Silver and pineapple, are immediate signifiers of colonialism, exploitation. Arce-Espasas captures that idea without any narrative.

So ethnicity, like sexuality and gender, is now difficult to mark, to identify, to characterize. Everything is about hybridity. At least in the exhibition. Modernism is still wielding its powerful force of materials and aesthetics as an end in themselves. It is important to think about the fact that artists have spent the last generation escaping the limitations of modernism. We seem to have come full circle.

Almost all of these artists are living in the US, but their family origin and often their birth place is in cities all over Central and Latin America, from many many different cultures; what most of them share is the act of immigration to the US, yet there is nowhere a reference to that in the work selected, with the single exception of Ignacio Gonzalez-Lang mentioned above.

Given the current rabid racism and prejudice against immigrants sweeping the country, I was disappointed not to find that some of these young artists engage that issue. Focusing on materials is a class issue, really, modernist abstraction and emphasis on process are both long standing approaches in Latin American art among the wealthy elite. The immigrants coming across to work in the US out of economic desperation are not stopping to focus on abstraction and materials. They are lucky if they can get a job.

Many of these artists, regardless of their own personal trajectories or the nightmare politics that they left behind in their own countries and in the US today, have taken on the privileged position of an apolitical modernism. We have no idea how they came to this safe landing, but certainly the emphasis on process in the interpretation of the theme “Here is where we jump,” encouraged that direction. Ironically, it could have led to something completely different, thinking about fence crossings. But perhaps NYC is too far from Mexico to be thinking about that possibility.

This entry was posted on September 21, 2013 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Ethnicity, Latino Art, Uncategorized.

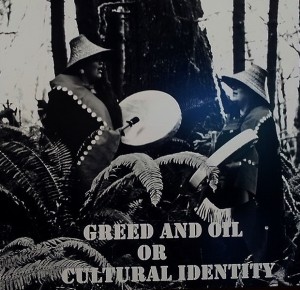

Part II Haida Gwaii: Thanks, But No Tanks

Through the windows of the Haida Gwaii Cultural Center, the beach and sea and sky and birds beckon us to embrace the stunning land that belongs to the Haida people today and for the last ten thousand years.

Although their traditional communities were decimated by small pox in the late 19th century, and by 1900 the Haida were reduced to only 300 people concentrated in two villages Old Masset on the Northern end of Graham Island and Skidegate on the Southeast, these villages today are active centers of Haida culture.

In 1985 Bill C31 enabled First Nations peoples in Canada to regain their status, and Skidegate welcomed people to return. This summer everyone was thrilled with the raising of the Legacy Pole in honor of twenty years of joint management of the islands “from the bottom of the sea to the sky”with the British Columbia government.

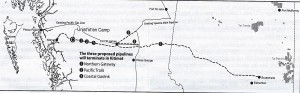

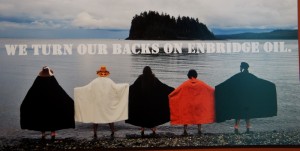

In the windows of the Haida Gwaii Cultural Center, curator Nika Collison has placed a succession of quotations from the hearings by the Joint Review Panel Hearings about the Enbridge Oil Company Northern Gateway proposal to pipe bitumen ( heavy tar sands oil, diluted by toxic chemicals imported from China) from Alberta and send it by giant tankers through these delicate shorelines and seas. The hearings were held all over British Colombia as well as on Haida Gwaii in 2012.

Tribal leaders testified eloquently, pointing out that the project failed to accurately measure the risks: “Northern Gateway does not appear to understand the responsibilities that flow from being inextricably linked with the natural environment.” (as quoted in the Haida Lass, Newsletter of the Council of the Haida Nation.) If you want to see the propaganda for the project from Enbridge you can read it here. They even have a link titled benefits for aboriginals, which gives them a ten percent share!

Hereditary Leaders at Enbridge Hearing on Haida Gwaii Image courtesy of Haida Laas newsletter of the Council of the Haida Nation

Collison alternates quotes between tribal leaders and other opponents with the words of the oil company. In this particular setting we can sense the absurdity of the oil companies’ perspectives to their fullest. We can understand the deep divergence of the two mind sets, one offering “jobs”and “economic opportunity” the other saying the land, sea and sky’s health is more important.

The quotations provide the entrance to “Thanks, But No Tanks,” 25 striking works of photography, animation, cartoons, paintings, and sculpture by both native and non native artists that all protest the pipelines and tankers.

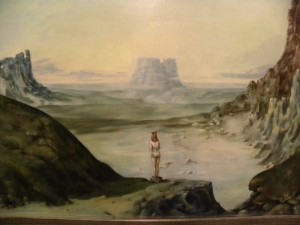

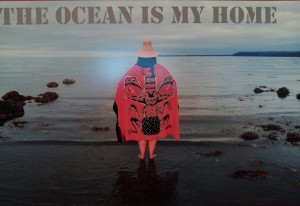

A young woman named Michaela McGuire was so affected by the hearings that she decided, as an amateur photographer, to make images about the significance of the threat of the tankers to Haida culture. The result was a series of staged photographs (developed in a collaborative workshop) with Haida youth, men and women wearing traditional regalia, standing by the sea or in the forest, with a brief text which brings home the meaning of the destruction of these lands for Haida people. ”

In addition, McGuire created a potent self portrait of her oil-soaked hand reaching out toward the camera, her screaming face visible through her fingers.

As curator Collison told me: “the strength of the photos catalyzed the show.”

Another dramatic response to the threat of the tankers came from Janice Tanton who had supported herself comfortably with sales to patrons from the oil community. When she came to Haida Gwaii for a residency, she completely changed her mind, and chose to oppose the project.

Her striking painting of “everyman” gazing out over Alliford Bay is one result of her distress. As she crossed Alliford Bay on a small ferry she was crossing over not only physically, but also emotionally and mentally, to another way of understanding the world. It is easy to understand this change: these islands exert a magnetic force.

Hanging from the ceiling in one room, is a paper mache head of Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper. It is one prop for a multimedia video called “Haida Raid 2: A Message to Stephen Harper.” an animated video that includes a rap song performed by JA$E El-Nino that begins:

“I met a Native man that did a span in Afghanistan

He even toked hash with a clan of the Taliban”

The animation by Haidawood includes Raven reprogramming the computer so that the oil is redirected into Stephen Harper’s face.

The curator also included a 1977 cartoon book Tales of Raven, no1 No Tankers, T’anks . Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas and John Broadhead

created it to oppose a previous disastrous project bringing the Exxon Valdez oil through Hecate Straits (the body of water between the BC mainland and Haida Gwaii- aptly named after the Greek Goddess associated with crossroads, entrance-ways, fire, light, the Moon, magic, witchcraft, knowledge of herbs and poisonous plants, necromancy, and sorcery.)

That protest successfully moved the Exxon Valdez project to Alaska, and we all know what happened next, an oil spill that has still not been cleaned up. Leaking tar sands out of old tankers could never even be cleaned up at all, so thick is the tar coming from the Alberta fields.

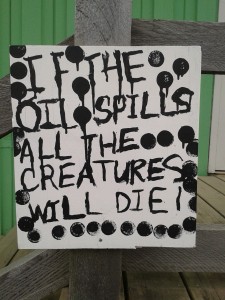

Among the many hand painted signs all over Haida Gwaii protesting the tankers was this one

Kayoko Daugert was accustomed to making joyful watercolors of nature, so this dark subject was a challenge for her. Catching Swarms of Invasive False Promises is a delicate watercolor that appears to be lighthearted until you look closely and see that the children are picking up globs of tar from the beach.

Photographs by Natasha Lavdovsky looked at underwater life, Pierre Leichner created tableux of toy soldiers in a delicate marine environment, possibly futilely trying to clean up, or suggesting that the tankers are like a war on the world under the sea.

Betsy Cardell’s hanging felted wool appears to have been eaten away by toxins; a big multimedia sculpture created collaboratively by 11 artists suggests all the forms of life under the sea :”The forest and ocean conceal little known secrets. While we sleep a symphony of cacophonous life explodes – if we don’t hear it, does it exist? Invisible, palpable, ruckus, rich . . . ”

One of the striking works in the exhibition is by Gwaai Edenshaw.

Hollow Promises: Two Hundred Years of Pain and Exploitation is cast of a fragment of a face mounted on a rusty oil can. Edenshaw’s work addresses the theme of prostitution: oil boom territory leads to a 600 percent increase in transient workers and transient prostitution. This ragged face exposes those ravages. I also read the piece as a reference to the renewed threat to the Haida from the tar sands tankers. It is accompanied by a short poem:

A hollow torn form smudged with greasy fingers.

A worn soul under the heel of “away from home”

The price of money . . . we cannot bear it.

The price of oil we will not carry it.

The irony is that at the same time as the exhibition, the Haida were creating the legacy pole honoring twenty years of cooperative management protecting Gwaii Haanas from the bottom of the sea to the top of the sky. Gwaai Edenshaw, was an assistant along with Tyler York, on the Legacy Pole with lead carver Jaalen Edenshaw. At the dedication, the Haida declared their “responsibility to conduct ourselves in a way that honors our ancestors.” Since those ancestors have recently offered fierce and successful resistance to destruction of their land, we know what to expect next if Enbridge continues.

Greeting resistors to Unist’ot’en Camp established on the line of the Northern Gateway pipeline 2013

Already there are mainland first nations camping on the route of the pipeline.

The plan is to fight in the courts because the First Nations have never given up their lands in treaties in Canada and they still have title to their land. But Stephen Harper, as Prime Minister, is doing everything he can to turn back the clock and take away indigenous rights, while talking as though he is providing economic progress. Raven’s action in turning the pipeline programming so that the tar sands squirts right in Harper’s face is a great idea. But Haida will be fighting with their bodies, minds and spirits, as will other First Nations groups, alongside US based tribes and many other groups who are also fighting the tankers and tar sands pipelines across the continent.

Stephen Harper is trying to “reset” the relationships with First Nations, meaning apparently to revoke their rights under cover of providing increased “opportunity.” The absurdity of these opportunities, to allow the complete destruction of the land in return for some temporary jobs in a toxic environment, is obvious from the vantage point of Haida Gwaii.

This entry was posted on August 28, 2013 and is filed under Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, ecology, economic imperialism vs democracy, First Nations Art, Gulf Oil Spill.

Buster Simpson// Surveyor

Buster Simpson arrived in downtown Seattle in 1973 only four years after Lucy Lippard came here to create what is now known as the first ever exhibition of conceptual art. The catalog for that exhibition, a stack of index cards, is part of the Seattle Art Museum permanent collection. and on exhibit in Minimal Art and its Legacy, at the moment.

Conceptual artists opposed the marketing of art and the separation of art from life. That led them to explore ordinary life and materials as art; they also believed in calling attention to the abstract systems and structures of art.

(For a few more specifics see my blog on a recent show in Athens.)

Liberated by the open ended ideas of conceptual art, Simpson, in collaboration with other artists and community activists living downtown, began to intervene in the fabric of the city. The work of these early activists eventually transformed thinking in the city. Today we have urban gardens everywhere, we have a variety of trees, we have bus shelters with seats (sometimes), all of these were unknown in the Seattle of the early 1970s.