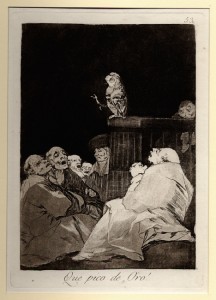

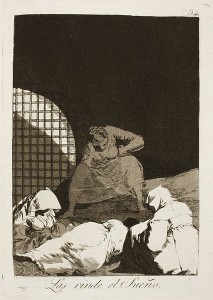

Goya’s Las Rinde el Sueño (Sleep Overcomes Them) and Que Pico de Oro (What a Golden Beak)

I have just acquired two prints by Goya from his Los Caprichos series. “Las rinde el Sueño” (Sleep overcomes them) and ““Que Pico de Oro!”( What a golden beak). According to the Davidson Gallery brochure, these prints are part of the fifth edition printed between 1881 – 1886. It is astounding that the gallery made them affordable. The thrill of having two real Goya prints in my life inspires me to write about them.

Los Caprichos relates to the idea of “sights,” as in Italian landscape conventions. In most cases Los Caprichos has been translated as “follies,” a more specific characterization of what Goya is representing.

Goya described the series as depicting “the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual.”

But these foibles are frequently represented by imaginary monsters or grotesque looking creatures and people. At the time that Goya created Los Caprichos, (1793 – 1798) he had just recovered from a grave illness that left him entirely deaf. Although he continued as the prominent court artist that he had been since 1789, he could no longer hear. While we might like to think that this heightened his observation of behavior as acted out by postures and clothing, Goya’s postures, as well as grotesque physiognomies, are emblematic of moral states: the artist declared that ” he has neither imitated other works, nor even used studies from nature . . . the artist may… remove himself entirely from nature and depict forms of movements which to this day have only existed in the imagination.”

“Sleep overcomes them” includes four women in various awkward positions. One women lies on the ground, and appears to be sick unto death, while the other three are keeping vigil (one is praying over her, the other about to cover her).

As Fred Licht has commented so brilliantly, the blackness above them does not suggest sky, the light does not give light, these are formal qualities that are imaginary; they enhance the emotional tenor of hovering between life and death. We do not know if these women are inside or outside, that ambiguity is also essential Goya. This print, like so many of Los Caprichos hovers between dream and reality, sleeping and awake, consciousness and unconsciousness. ( Fred Licht, Goya, Abbeville Press, 2001 and Goya, The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art, 1981.)

One analysis of the Caprichos suggests that there are four aspects to the series, condemnation of society’s traditional vices, deceit in relationships between men and women, protest against abuse of power, and satirical comments on poor education and ignorance.

Sleep Overcomes Them would connect to these themes. The vice here is one we are familiar with today, the desperation of the poor who lack sufficient housing, food, and love. The seated woman is the center of the print, she has firmly planted her feet conveying her strength and endurance, but her upper body suggests, at this moment, almost surrender to defeat, both in helping the woman lying on the ground, and in overcoming her own adversity and poverty and exhaustion.

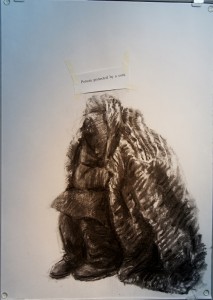

The only drawings I have seen of homeless that somewhat echo the subtlety of Goya are by Olga Chernysheva, a Russian artist. Her drawings reflect the legacy of figurative training in the old Soviet Union. She suggests survival based on a single luxury that enables life to continue typed in small letters on a piece of paper attached to the drawing, a coat on the left, a smoke on the right. Chernysheva spends a lot of time walking the streets and observing the people left behind in the new capitalist Russia, but as with Goya, these postures convey more than factual observation.

Long before Marx, Goya recognized that the wealthy sit on the backs of the poor, that the privileged are essentially the monsters and hypocrites that we see in Los Caprichos.

The dialectic partner of Sleep Overcomes Them is my second Goya, Que Pico de Oro! (What a Golden Beak). We see a parrot sitting on a podium like box, gesturing as in giving a speech. Surrounding him are men in various stages of consciousness. The image evokes a courtroom scene, with a single figure behind the parrot, and the others clustered below him. The figure in the foreground seems to be in a worshipful position, others have raised their heads and opened their mouths as though entranced. Another man looks dubious, two others look like collaborators, evil smirks on their faces.

How can I see this and not think of the Trayvon Martin trial, (only one random reference, there are hundreds of course) whose verdict today let off George Zimmerman from any wrong doing. What but a golden beak and and half conscious magistrates would fall for any argument that let off a man who had pursued a young unarmed black teenager in a car and then on foot, then shot him dead in the heart. Michelle Alexander has explained the deep racism of the Criminal Justice System in her book The New Jim Crow. If you have read the book, the verdict is not a surprise, but it is still horrifying.

But What a Golden Beak also speaks to me of our government, with its golden tongue, particularly of President Obama, who spins webs with his speeches, deluding and lulling us with his words, even as his deeds are leading directly to the death of so many people as well as the planet

itself.

To return again to Fred Licht , Goya is the “first spokesman of a modern view of man that despairs of our intellectual capacity, has lost its faith in the essential nobility and purpose of our destiny, and stands bewildered within a dark universe in which law, order and dignity are no longer visible or attainable ideals.”

That is pretty powerful and of course I myself am an activist, and believe resistance and outrage is essential as have thousands of people this week in response to the Trayvon Martin verdict. We were sleeping in a myth of progress on civil rights, and now we awaken, but to what state, to what future? That is for us to determine.

This entry was posted on July 19, 2013 and is filed under art criticism, Goya.

Art and Politics at the Seattle International Film Festival

There were powerful politics in many of the films at the Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF). The back stories for the making of the films as well as the politics of their release are frequently almost as dramatic as the films themselves, filled with politics, protest, government suppressions and creative courage. All of the movies exist in various relationships to documentary, fiction, real life, and real world events.

Part I A World Not Ours directed by Mahdi Fleifel

I think the film that affected me the most was A World Not Ours shot from the inside of a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon that the filmmaker, Mahdi Fleifel, had lived in as a child. Many members of his family are still there.

I just re read the program notes and I could hardly believe that it was the same movie I had seen. It is characterized as “funny, nostalgic and uniquely engaging.” Actually it was depressing, claustrophobic and deeply revealing.

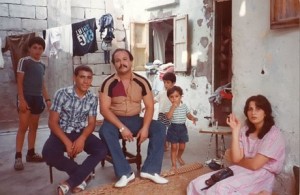

The film was shot with a hand held camera. The filmmaker’s father, and mother “escaped” ( they are still refugees) into the middle class because his father had a job in Dubai, where Mahdi and his brother were born. It is not clear how his father managed to leave, but the filmmaker’s uncle and grandfather are still there. The family has a tradition of home movies, so in making this film Mahdi Fleifel was able to draw on those early films, both in Dubai and in the refugee camp, Ain El Helweh, where he lived as a child.

We have all heard about Palestinian refugee camps. But never had I gained such a sense of what it is like to actually live in one, be trapped in one, unable to work or leave. This one has 70,000 people in one kilometer. It has been in existence for 60 years. The people have small homes, but what really depressed me was the fact that so many young people are not allowed to work, leave, or do anything. This fact was conveyed through the filmmakers interaction with his friend Abu Eyad, the real star of the movie. We see his life up close, we see his story, we hear his words, we understand what it means to be a perfectly competent young man and unable to get a job (he has a job with the PLO part time, but he quits it in disgust with Arafat at a certain point).

II Closed Curtain directed by Jafar Panahi

Also conveying a sense of being confined was Closed Curtain. Film director Jafar Panahi is under house arrest in Iran. This is the second film I have seen that he has made since he was put under house arrest. The first was This is Not a Film (smuggled out of Iran in a cake). The Iranian director is currently under house arrest, convicted of “making propaganda against the system” and banned from writing scripts or shooting pictures for the next 20 years according to the Guardian newspaper. The first film was simply his daily life in his apartment, the second film, set in his seaside villa, suggests isolation, paranoia, and melodrama. The filmmaker who was almost the sole actor in This is Not A Film, here arrives late in the movie, and the characters that precede him are then understood to be figments of his imagination.

The curtains are closed for most of the movie, the sense of oppression and claustrophobia is everywhere. A subplot is a pet dog and the careful removal of his litter on a regular basis; Panahi takes the trivial act and makes it into state resistance: the dog is also in hiding because of the government policy of killing pet dogs.

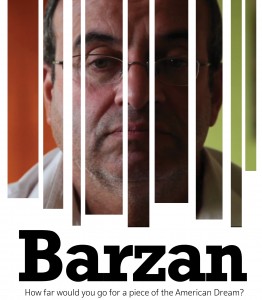

III Barzan directed by Seattle Globalist

Also making reference to confinement is Barzan a film by Seattle Globalist, a University of Washington Department of Communications program (separately funded). Barzan was the nickname for a man who was living in Bellevue. Because of the complexity of the story I will quote description from the Globalist website

“Barzan is a film about a man who simultaneously embodies two fundamental myths of 21st century America: the American dream of peace and prosperity and the bloodthirsty terrorist bent on destroying that dream.

Sam “Barzan” Malkandi, an Iraqi refugee to the US and beloved father, was working toward his piece of the American Dream in a Seattle suburb. But a footnote in ‘The 9/11 Commission Report,’ connecting him to a high-level Al-Qaeda operative through his childhood nickname, changed everything.”

The film is also about detention and deportation. The procedures that Malkandi goes through once he is accused and detained are extraordinary: he appeals before a judge ( immigrants in detention do not have access to the jury system because it is a civil procedure not a criminal procedure, although the detainees are treated like criminals as we saw clearly in the film. Visitations are behind glass separation barriers. And the health rules for criminals are not followed, re diet, healthcare, outdoor time.

IV Dirty Wars directed by Richard Rowley

I saw Dirty Wars as part of the festival, but it is now in theaters and it is an extraordinary film. Jeremy Scahill is the leading actor, the director is Richard Rowley and the film score is by the amazing Kronos Quartet. Scahill narrates the story of his investigations of atrocities and we follow him as he visits families with suffering and tragedies that the US has caused by its mistakes and its intentions. Scahill starts in Eastern Afghanistan in a small village, then he moves on to Yemen and the killing of two Americans. These are stories of the massacre of innocents and the US disregard for human rights, international law, or any normal concern for human life, but the flavor of the film is a mystery, and what he uncovers is truly evil. I had the good fortune of hearing Jeremy Scahill speak about the film during SIFF. He is modest and understated. How he can have so much courage and persistence is unbelievable. The book is huge, but we should all buy it to support him.

V After the Battle directed by Yousry Nasrallah

With Egypt erupting once again, the film After the Battle is all the more timely. It follows a story of one of the men from the tourist trade at the pyramids who rides his camel into Tahrir Square. He is ostracized by many people for the initial act and further because he was pulled off his camel and beaten. His children are bullied and mocked in school. A liberal young woman working for an NGO becomes infatuated by him and his family, and the complexities of his story emerge. It is a story of class, economics, and power relationships. The movie was shot in real time, and near the end, the film making is actually caught up in a Tahrir Square protest. The female lead was verbally abused. Here is another analysis of the film from a film critic’s point of view. The film critics found the movie less than compelling, but I found the class and political intersections riveting. The director Yousry Nasrallah has made a documentary, a fiction, and a story of individuals as he says “refusing to be victims of large social issues.” Actually though, that is not quite true of the camel driver Mahmoud.

6 Coming Forth By Day directed by Hala Lotfy

Another film from Egypt Coming Forth by Day is by a new female director Hala Lotfy . She follows a mother and daughter as they carry for their paraplegic husband/father. They lovingly try to feed him and nurse him. The film is excruciating to watch because the pace is very slow, we feel we are in the small house also caring for this helpless man, but the result is a rare glimpse into the struggles of ordinary people. But I couldn’t help feel that the young woman who wandered around Cairo on her own and even spent the night outdoors, was a little unrealistic. In no country would a woman sleep outside without concern for her own safety. In Egypt where we know that women are frequently attacked in public, it seemed all the more improbably.

7 The Attack

Finally The Attack brings us back to the Israel Palestine crisis. The film is an original take on the situation, a wealthy and successful Arab Israeli doctor discovers that his wife is responsible for a suicide bombing. His journey to his own roots in the West Bank and to the reasons for her actions are riveting. The film by Lebanese director Ziad Doueiri based on a novel by Yasim Khadra has been banned in Arab countries as well as in Israel. Both Arabs and Israelis accuse him of favoring the other side. But that is the strength of the movie. We see both sides.

SIFF really outdid itself this year in terms of showing international films with substance. And of course, I am only writing here about a fraction of the total. They had a special grant for the movies from Africa.

The films I saw constituted a virtual Middle Eastern film festival in themselves. Film is a crucial medium for revealing stories beyond the clichés of the news: we meet people of compassion, courage, and tragedy. We can learn a lot about the damage that the US is causing in the world, as well as the toll that power politics takes on both artists and other people by seeing films such as these.

This entry was posted on July 10, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in Beirut, Art in War, Art of Democracy, Film, Uncategorized.

Eleanor Harvey’s groundbreaking exhibition The Civil War and American Art

Eleanor Jones Harvey exhibition “The Civil War and American Art” is a fundamental reinterpretation of American painting. As we are marking the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, and the eve of the Fourth of July, it is a fitting moment to honor this amazing work of scholarship. Here is Timothy O’Sullivan’s photograph of the Battle of Gettsyburg “A Harvest of Death”. There are no heroes here.

When I saw the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in early June, I was astounded at the new perspectives I gained on paintings I have known and looked at for decades. In addition, the book that accompanies the exhibition, which is entirely written by Eleanor Harvey rather than a collection of essays by various scholars, is a beautifully written tour de force of insightful analysis of the art. The sumptuously reproduced images give us the opportunity to look as closely as the author.

In this review I will emphasize the theme of landscape, although in the exhibition abolition, slavery, and racial relations are all included.

The text uses only writing contemporary with the war as sources. So for example Frederick Church’s painting of Icebergs, was retitled The North, on the day after the war began, in order to suggest that this landscape was associated with the unsullied moral stance of the North.

Harvey, in a lecture which you can view here Part I and here Part II online, reveals that she has been working on this exhibition for thirty years. I am not surprised. Her careful study of the works as well as the nineteenth century sources has yielded an invaluable contribution to our perspectives on nineteenth American art, our understanding of the relationship between art and war, the relationship between artists and national turmoil, that completely up ends former interpretations. The cliché was that artists, especially landscape artists, “took a pass” on the war, as Harvey succinctly puts it. But a second look at this painting of A Coming Thunderstorm” by Sanford Gifford tells a different story. The thunderstorm is about to descend on the land. This painting was actually owned by Edwin Booth the brother of the man who assassinated President Lincoln very shortly after the end of the war. So in this case, the painting has even more portends of disaster.

Harvey makes no mention to any recent war (her most recent reference is 9/11 comparing its impact on the American psyche to that of the Civil War), she mentions Bosnia briefly, but not the perpetual wars of today and the effect that they are having on our national psyche. The perspectives of artists and poets and intellectuals in general caught in the midst of a national trauma in the midst of the Civil War is crucial to our understanding and an example for artists working today.

In a way, these artists had an easier time than today’s artists in how to go about representing a traumatic period in US history. There were widely accepted metaphors, generally accepted ideas among a fairly small class of elite cultural leaders and their audience. These are the metaphors the Eleanor Harvey has explained in her exhibition and in more detail in her comprehensive book.

She calls her endeavor a “forensic exploration” of how artists “absorbed” the war, and dealt with it as it was going on. She includes only works done when people did not know what was going to happen, art in the moment in the midst of the war. She starts with a painting of a meteor, and quickly links that to the language around John Brown (of Harper Ferry fame) as the meteor and the portent of war. She comments that people of this era were trained to look at multiple meanings, unlike today.

The thunderstorm or the volcano as references to slavery, were often repeated references.

The Aurora Borealis, which made a spectacular appearance on the East Coast in 1859, was also an apocalyptic event. So while there were multiple meanings, they were widely repeated meanings that everyone accepted and understood. There was also a narrative of North and South, whichever side you were on, the reason for the war was clear, it was about economics, with slavery as the looming, terrifying face of those economics.

Harvey’s exhibition includes artists who were soldiers, artists who were journalists, and war photographers. Very few of them stayed out of the battlefield. Jones found artists from both the North and the South to include, and, in particular the photographs of George Barnard showing the devastation of the major cities (she points out that he chose to settle in the South after the war.) This photograph emphasizes the overwhelming disaster by including a passive figure in the foreground.

Harvey’s exhibition opens a big door for us to think about artists and the current trauma of our society. Her thesis that everyone was affected by such national traumas when applied to today might be difficult to determine if future scholars try to rely on contemporary sources. The record of today’s traumas and trivia is on Facebook, Twitter, and Fickr and it is quickly crowded out by the next event. Where will that material be in fifty or one hundred years? Archived digitally? Or vanished into the ether.

Where do artists today go to represent our current national crisis.

Harvey’s introduction reminds us that the American landscape was anointed sacred by white settlers and their elite writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson; it was seen as a Land of Eden. The Civil War destroyed that Eden, the battles were fought in fields that were ravaged, their crops now dead bodies. But afterward almost all of the artists went out West and discovered a new Eden ( of course Native Americans would see all this very differently).

Now we have the new stage of destruction of the American land from East to West, as energy companies pursue ever more ferocious extractive practices for short term energy goals.

We are in a huge crisis on every side. We need artists to speak about our collective national trauma once again. While individual artists are doing so (see my book Art and Politics Now), we need large collective discourses (the Occupy Movement was that briefly), we need all artists, poets, writers and intellectuals to create new metaphors. Right now.

Here is an idea for a place to start: the redefining of genre painting

(of everyday life) when the Civil War exhibition ends.

Winslow Homer’s Veteran in a New Field on the left is analyzed by Harvey as a soldier who is actually trapped in the wheat field, with a dense field in front and his exit closed in by the wheat he has cut. His hat barely breaks the horizon line. It speaks of a land and people without a way forward.

Homer’s Cotton Pickers on the right, according to Harvey’s analysis, suggests one woman as continuing with the old ways, and the other looking beyond to the future.

Of course in both of these cases, the real sweat and pain of the work

(especially for cotton picking) is no where in sight.

But these metaphors of change, of challenge, of obscured vision, can perhaps be applied to today’s situation. Here is Edward Burtynsky’s “Mine” the present landscape of the earth. The link is to his paintings of the production of oil. He speaks to where Eden has gone.

This entry was posted on July 3, 2013 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, Art in War, Civil War, Uncategorized.

Sopheap Pich revisited

In November 2011 Sopheap Pich came to Seattle for a one person exhibition at the Henry Art Gallery. He also created designs for a play about the experience of Cambodian refugees. I wrote about these in my blog.

Although at that time he was already having a one person exhibition in New York City, he has since become a star, showing in Europe at major international exhibitions, and most recently, in a one person show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a second one person show in NYC at Tyler Rollins.

Sopheap Pich fascinates me with his balance of abstracted, but easily recognized, form, material, and content. He has detailed labels for his work which means that we cannot mistaken the deeper meaning of the work, even as we experience his sense of beauty, a beauty that is forged through his great suffering as a child and young adult and that of his fellow Cambodians.

Even as we are deporting Cambodians who came here as children with their parents, because of a minor teenage offense for which they have already paid their time, ( as seen in the film Sentenced Home), Sopheap courageously chose to return to Cambodia in 2003. He went through a major transformation of his work and rediscovered his ancestral heritage, working with rattan and bamboo.

His success means that he can employ people to help with his work:the skills that he uses along with his helpers, are traditional skills, harvesting, boiling, cutting, weaving. He is keeping those skills alive, transforming their purpose, and telling the world about Cambodia, its history, its poetry, its sense of nature based abstraction, the scars of its wars both visible and invisible, and now also, the scars of greed and development.

As we look at his work, we sense all of those aspects, but in no work more than in his exquisite Buddha 2, 2009. The Buddha has only a head and shoulders, the body is unformed and the streams of rattan hang down to the floor, their tips dipped in red. The Buddha is in a gallery with historical Buddhas of Cambodia, it seems to be carrying on a conversation with those Buddhas, to be speaking from today to the past, to be saying, I am scarred, my form is disintegrating, but I still survive. The artist’s wonderful idea to embed his works in the historical galleries of Cambodian art is nowhere more resonant than in this room. It made my heart stop for its beauty and its tragedy.

He spoke on the label about living as a child in Battambang near a Buddhist temple that he passed with water buffalo he was taking to a rice field. Inside of the temple he saw bloodstains, from the violent murders of the Khmer Rouge. At that time his family were still living on their own, not long after they were forced to move to a Khmer Rouge camp, where they did forced labor. I was stunned that a person could experience so much trauma and change in their life and survive to create this great art. From herding buffalo to an art exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but also staying true to himself, at the same time that he is a celebrity in the art world.

The Morning Glory of 2011 sprawls across the floor of the Metropolitan. It seems lazy and lush, somnolent almost. The artist explains that this was a primary source of nourishment during the Pol Pot regime, and therefore a time of starvation, as morning glories have no nutritional value. It also represents a false glory, it blooms and quickly dies immediately, The sculpture includes a blooming, a fading, and a budding flower. It draws on the artist’s knowledge of the plant from the inside out.

Another piece, the double stomachs, also speaks of not only an organ, but also an indirect reference to starvation and the bloated stomachs of undernourished children. These swelling forms seem to dance in the gallery, in a strange partnership of swollen shapes.

Junk Nutrient represents an intestine( made of woven ratan and rubber detritus) stuffed with trash that is spilling out the end. It was trash taken from a lake where Sopheap had his studio, but in this vivid image it refers to the pollution of the body and the mind, as people are transformed by “progress” and development.

The tower of Upstream, based on the fish trap from his family’s traditions, inserts itself as a peasant tradition into the high art of an ornate ceiling.

And finally works that appear as minimalist grids, but which are made from beeswak, tree resin, dirt, and make reference to the destruction of a beautiful valley by development based on greed. We can feel the scarring, burning of nature in these subtle reliefs.

These current pieces address present day Cambodia. The grids are abstractions, but here too, we can be fooled into simply seeing them through our trite Western cliches. Oh grids, yes, minimalism, but actually there is a long tradition of abstracting from nature in Cambodia.

( this is a detailed close up view)

The roots of these abstractions are deep in Cambodia’s past. We like to think that US artists, or European artists, discovered abstraction, but we know that it is an old old tradition. The artist makes clear that the materials are specific to this location and speak to his own sense of loss at the destruction of the land.

At the end of the exhibition at the Metropolitan was a short video showing the way in which the artist gathers the bamboo and rattan from the forest and, with his assistants, make it usable for art. We in the West know rattan and cane chairs, but the material has been used for centuries for practical purposes. Sopheap takes those original forms and transforms them into contemporary sculptures that speak to everyone. It is sad and not surprising that all the reviews of this exhibition emphasize the artist’s process and materials, his forms, his abstractions, with no reference to his content. The artist himself has declared he is not a political artist, and he was contrasted to other more political artists in a recent Art in America article.

But I see this work as deeply political, in the sense that it is telling us so much that we don’t know with his materials and form. These sculptures are pure poetry, but poetry with a point, a point about war, hunger, starvation, greed.

Another exhibition about Cambodia at Asia Society by Vandy Rattana called “Bomb Ponds” was also poetic and moving. Photographs of apparently bucolic scenes of ponds in the midst of rural farmlands are actually something quite different.

A series of videos interviewed contemporary farmers about the holes left by bombs from 1970s, their toxicity, their damage to the land, their ongoing presence, their dangers.

As the US has long since forgotten our Cambodian carpet bombing, the scars of that war live on in the land.

These long range environmental aspects of war are rarely addressed by contemporary artists. Sopheap Pich uses the metal recycled from left over war materals to make wire that holds together his rattan structures. But much more often this detritus is simply a toxic presence in the land for generations of people who are the innocent victims of war.

This entry was posted on June 22, 2013 and is filed under Art and Ecology, art criticism.

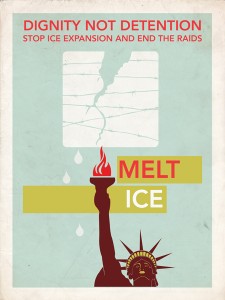

Art about Detention and Immigration as a terrible new law makes its way through Congress

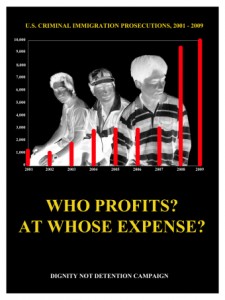

The Detention and Deportation system in the US is already out of control. The average population of detainees has escalated from 5,000 in 1994 to 33,000 in 2010.

The bill under consideration is mainly about defense contractors making money with more fences, drones, and other equipment.

Only 8 out of 350 detention facilities are operated by the federal government. The rest are run by private corporations like Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) and the GEO Group, Inc who are making billions of dollars. They charge us, the taxpayers, about 170. per day per detainee. Detainees are treated like criminals with jumpsuits and chains, but they don’t even have the rights of criminals to a lawyer or due process.

This process is almost invisible to the US public, although Detention Watch Network is working hard on changing that. They have a “Dignity not Detention” campaign, that includes videos and posters.

In the Northwest, we held a vigil/rally at the Tacoma Detention Facility on Mother’s Day that brought in the Backbone Campaign and the Raging Grannies, as well as more than 100 people.

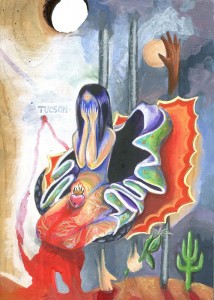

In Arizona an exhibition specifically about ICE detention included some crucial statements by the artists. I am looking forward to finding more artists who address this issue. Simon Arizpe’s work is outstanding for its subtlety and sophistication, even as it presents us with a very specific and horrifying practice. He is intentionally creating something that appears to be a beautiful object that draws us in, even as he then tells us what we are looking at.

Simon Arizpe

For many detainees the first right that is stripped away from them is control of their bodily fluids. A common practice for interrogators is to deny the person water for long periods of time or conversely, to give them water and then restrict their ability to urinate.

To illustrate how politics can overshadow the basic human right of having a working, healthy body I will look to a practice used by illegal border crossers in the Sonoran dessert. These travelers are able to thwart dehydration by filtering their own urine through a simple process of two cup evaporation. I will use this same technique, which is talked about but rarely seen on this side of the border, to put into perspective the humility and isolation people go through when detained.

I will build a large-scale two-cup evaporative system 3′ x 3′ x 2′, mounting it in such a way that it appears as a beautiful design object and a working evaporator, instilling it with the weight and magnitude that the object has when it makes a life or death difference for detainees and refugees.

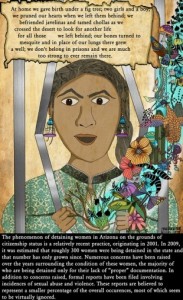

Shloka M. Ettna, “Women in Detention”

At home we gave birth under a fig tree. Two girls and a boy. We pruned our hearts when we left them behind; we befriended javelinas and tamed chollas as we crossed the desert to look for another life for all those we left behind; our bones turned to mesquite and in place of our lungs there grew a well; we don’t belong in prisons and we are much too strong to ever remain there.

The phenomenon of detaining women in Arizona on the grounds of citizenship status is a relatively recent practice, originating in 2001. In 2009, it was estimated that roughly 300 women were being detained in the state and that number has only grown since. Numerous concerns have ben raised over the years surrounding the condition of these women,the majority of who are being detained only for their lack of “proper “ documentation. In addition to concerns raised, formal reports have been filed involving incidences of sexual abuse and violence. These reports are believed to represent a smaller percentage of the overall occurances, most of which seem to be virtually ignored

Amy Hagemeier on the experience of women caught up in the immigration dragnet:

“The Shame” explores the unique space women occupy in immigration and incarceration. Not only do immigrant women deal with racial and economic inequality, they must also confront gender violence. This compounds the amount of abuses to their bodies and their spirits- to be separated from children, to be sexually assaulted.

“The Shame,” through the hands in the background, also acknowledges that incarceration could be extended to include the economic system that has determined what roles we are to play (ie. economic refugee), leaving us with no viable alternatives.”

Wesley Creigh

There is a desperate case for reforming the way ICE conducts their detention of migrants. Women migrants in particular make up a large, unseen population on the outskirts of our communities whose specific medical, emotional and familial needs are not being met. As women continue to be subjected to these indefinite and non-criminal incarcerations families will continue to be separated and children will continue to be caught up in the equally bureaucratic and convoluted CPS (Child Protective Services) system. The trauma that occurs from these separations and imprisonment is long lasting and severely damaging. Yet this is something that we are ignorant about because we do not have to face it at all. ICE has made sure this population is virtually invisible to us. The more we can inform ourselves the more we can begin to struggle for reform.

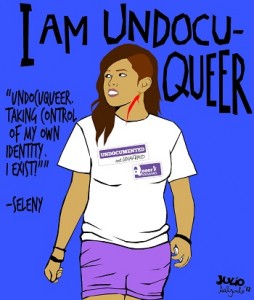

Julio Salgedo has created a series of posters that demonstrate a sophisticated graphic aesthetic as well as a clear statement of the issues

Here is another “Why I travel” ” I am here for the families who are afraid to leave their house.” This is part of the nopapersnofear campaign.

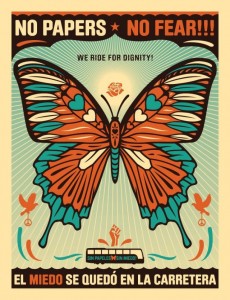

“Fear is left on the road”

The monarch butterfly that migrates throughout North America from Mexico to Canada is the symbol of this movement.It is an ancient symbol of freedom

It has caught on with many people. Here are some children from May Day march in Seattle

The description below of the current disastrous bill is from the Detention Watch Network website where there is a wealth of useful information.

“Rep. Gowdy’s SAFE Act Will Lead to Massive Detention Expansion (WASHINGTON) – The House Judiciary Committee is expected to begin markup of Rep. Trey Gowdy’s (R-SC) Strength and Fortify Enforcement (SAFE) Act legislation, H.R. 2278, on Tuesday, June 18.

If enacted, the SAFE Act will dramatically increase detentions and deportations and create an environment of rampant racial profiling without fixing the immigration system’s fundamental problems.

The SAFE Act would do the following:

Authorize excessive spending increases to build and expand detention facilities across the country. (H.R. 2278: Title I, Sec. 107)

Undermine individuals’ due process and equal protection rights under the law by allowing for indefinite detention and significantly increasing the number of immigrants subject to mandatory detention without the right to a hearing before an immigration judge. (H.R. 2278: Title I, Sec. 108, 111; Title II, 301, 310; Manager’s Amendment)

Undo hard-won progress to improve conditions for immigrants in detention by reverting to minimal U.S. Marshals Service custody guidelines. (H.R. 2278: Title I, Sec. 108)

Funnel more immigrants into the detention and deportation system by expanding the grounds of deportability and by authorizing states and localities to create and enforce their own immigration laws.

“The SAFE Act resurrects the much discredited Sensenbrenner bill from 2005 and proposes an extreme departure from existing immigration law. If passed, the SAFE Act would be disastrous for the bipartisan efforts to enact just immigration policies,” said Andrea Black, Executive Director of DWN.

“Not only will it expand detention, it will result in the prolonged and unconstitutional incarceration of thousands of people, under inhumane conditions, without any safeguard of their civil and human rights.”

Detention Watch Network calls on Congress to vote against the SAFE Act and instead to repeal mandatory detention and reduce the unnecessary, inhumane, and wasteful detention of immigrants. Until immigration reform is enacted, DWN calls on President Obama to put a moratorium on detentions and deportations and stop the unnecessary separation of thousands of American families.

This entry was posted on June 20, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism.

Under my Skin Artists Explore Race in the 21st Century

Mary Coss in collaboration with teenagers who wear hijabs. The wire sculptures are images of the girls, the work included their art work and their conversation about wearing hijabs

What a difference a decade makes. In 2004 the Wing Luke Museum held a pioneering exhibition about racism called “Beyond Talk: Redrawing Race.” It was catalyzed by the racism,particularly against Arabs, that burst into the open following the World Trade Center attacks,. It included 12 artists showing twenty artworks, with educational and interactive components for every work in the exhibition; each work also asked for our responses in a journal nearby. It also was an early example of an art exhibition with an internet component that teachers and the general public could access easily. It encouraged book clubs, discussion groups, library gatherings on race, and many other specific actions. Southern Poverty Law Center was a partner and the website included their program ” teaching tolerance.”

I analyze this exhibition in Chapter 5 “Exposing Racism” in my book Art and Politics Now, and compare it to the exhibition organized by Coco Fusco and Brian Wallis “Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self.” I suggest there that the Wing Luke with its community based model was far more effective in penetrating the deep ignorance (among white people) about racism and how it operates. They moved beyond simply representing racist images, and into engaging the audience in their own perspectives.

Now the Wing Luke Museum returns tothe topic of racism with “Under My Skin, Artists Explore Race in the 21st Century.” The catalyst today seems to be exploding (or exploring) the myth of the “post racial” society, And of course, post race does not mean post prejudice. This exhibition is less interactive than the 2004 exhibition, but in some ways it is even more affecting, because of the intensity of the art works.

But it is not at all a reprise of the previous exhibition.

First of all there are twice as many artists, and consequently a larger range of topics and media. There is also less emphasis on the national and global political and cultural environment and more on personal experiences.

Another striking difference is the fact that two artists refer to loss of identity as a person of color, First there are the paintings by Laura Kina whose white-appearing daughter is the signature work of the exhibition. She represents the fifth generation in the artist’s family in which successive marriages altered skin colors.

A ceramic work by Native artist Erin Genia charts the dilution of racial color as though on a clock face with faces losing their color as you progress around the clock. Genia is refering to the blood quantum rule for racial membership in native tribes. The federal government declared that a native person must prove 25 per cent native blood with documentation. Obviously over time, fewer and fewer people will qualify.

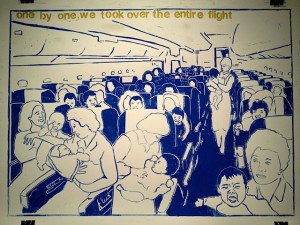

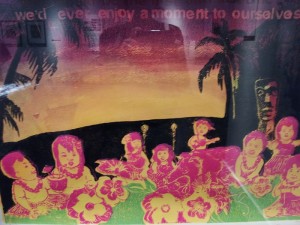

A second and related theme, is cross cultural adoption or interracial families, as explored in the stunning prints by Darius Morrison, a young man adopted as a baby from Korea. He re imagines the flight of the babies from Korea even giving them a party in Hawaii a wonderfully creative approach.

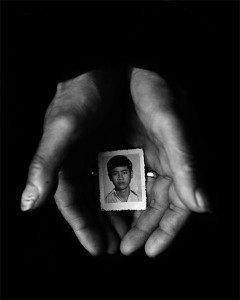

The poignant photographs by Canh Nguyen suggest the emotional distance that occurs when someone is far from their cultural roots. His black and white photograhs include this work of his father’s hands, holding the only photograph of himself as a boy that survived his trip to the US after the Vietnam war. He raised three children a a single parent. Another artist Minh Carrico suggests the distortions that occurred in his childhood, raised by a Vietnamese mother and a white (Vietnam Vet) father in Arkansas: he digitally adds frightening masks on top of his childhood photographs.

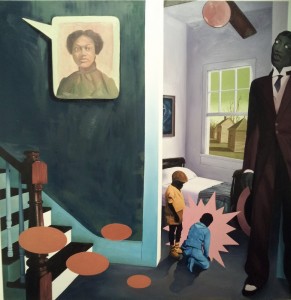

Two artists appeared in both exhibitions: the wonderful painter Ronald Hall who frequently bases his work on intense moments in African American history. His painting has become more complex and layered in the ten years since the previous exhibition. The topics addressed confront us immediately, but then the horror of them sinks in. They really need no explanation.

Polly Purvis, a white artist who has been living with and documenting the Swinomish Tribal Community for ten years. Here she includes both photographs of a Powwow and its opposite, racist kitsch that stereotypes Indians.

There are other historical works, referring to the Japanese Internment, in the sculpture woven or rose branches by Fumi Matsumoto, and Kathy Budway’s video which combines historical footage from the Civil Rights movement and students in her ESL class who explode the popular media stereotypes of African Americans by studying outstanding African American historical figures.

Speaking of students, two other works were the result of working with children or young adults. Mary Coss encouraged Somali girls wearing hijabs to talk about their experiences ( see her wire sculpture portraits of the girls at the top of the blog) .

Kathleen McHugh invited children to identify themselves beyond skin color in a large collaborative drawing with a single tan color

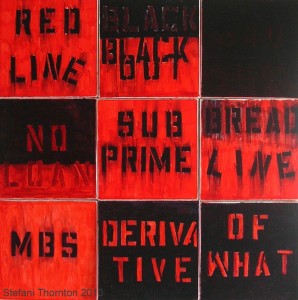

So what else did we find in the exhibition? Real estate: red lining in confrontational paintings by Stefani Thronton.

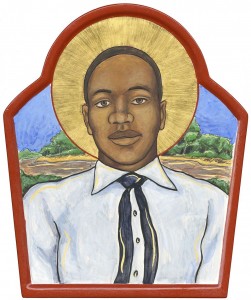

urban violence in the icons by Jasmine Iona Brown.

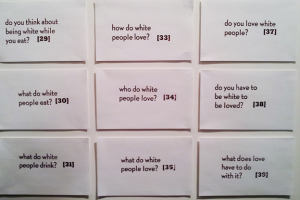

Naima Lowe turns the tables on white people with her 39 questions for white people that consist of all the dumb questions people of color are asked.

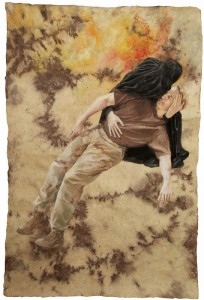

Violence against women is the big topic in the work of Tatiana Garmendia, whom I have written about before here. Her installation also includes works from another series called Lamentation. These surprising images of a woman covered in black cradling the body of an American soldier suggest that mourning is a universal process that has nothing to do with race or culture. Everyone has the same feelings when someone dies.

Garmendia has a global perspective, although her opposition to violence against women is based in a personal experience: she witnessed it as a child in a Cuban prison shortly after the Communist revolution. She has carried a terrible memory of that with her and only now is able to refer to it in her work.

In looking at a show like this, the tendency is to stay outside of the issues represented, but actually, all of these works touch everyone. We are all part of a society that practices racism in so many ways, we are all perpetrators, whether consciously or unconsciously, we are all prejudiced. So the exhibition includes a discussion area that allows people to talk about racism and prejudice.

Near that comfortable place are large photographs that were displayed in the Central District in an empty lot by Inye Wokoma working in collaboration with Jenny Asarnow and NKO. The images present a few of the people who live nearby. They are large photographs, each person is dignified and self sufficient. Accompanying this work is a series of interviews with people talking about the neighborhood.

There is also an online facebook, youtube and audio as part of this project.

Conversation and familiarity is one key to ending prejudice and racism.

This exhibition was very personal, there was no reference to larger reasons for prejudice, like the “war on terror,” or our immigration policies, that are locking up thousands of people in detention and deporting them across our country. There was no reference to capitalism as a means of dividing people, creating terrible economic disparities and unequal access to education and a leading cause of urban and domestic violence; there was no reference to our enormous privatized prisons that are operated for profit by private companies ( as are the detention centers).

But personal as it was, the exhibition does offer a way forward: understanding experiences that are based on cultural difference, learning of the difficulties that people face because of their racial identity, helps to develop at least awareness. One on one dialogue is where we can start. It is those big generalities about terrorism and war and “the other” that create unconscious fear. Fear leads to a desire to protect ourselves, and that is the basis of prejudice and discrimination.

I feel fortunate that I grew up in New York City, where I was immersed in a great mix of people not only of different racial backgrounds, but also different economic backgrounds, religious backgrounds. It gave me a good preparation for understanding that we are all simply human beings.

Don’t miss this important exhibition, and plan to go more than once. Here is another review on the website of the Seattle Globalist. I haven’t seen any other press coverage.

This entry was posted on June 16, 2013 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Feminism, indians, Racism, Uncategorized.

Beyond G(u)ernica and Bilbao: Contemporary Culture in the Basque Country

Many leaders of the contemporary art scene in the Basque country came to University of Reno, Nevada, last week to speak at the Center for Basque Studies in a symposium called “Beyond Guernica and Bilbao Relations Between Art and Politics from A Comparative Perspective.”

Artists, curators, critics, theorists talked about their work, the institutions that they lead, the exhibitions they have curated, and the relationships between art and politics in that area. It is hugely complex.

Of course the point of departure was Guernica painted by Pablo Picasso in 1937. This iconic painting of the bombing of civilians in the sacred Basque city of Gernica holds a perhaps unique position in that it is highly regarded by art historians and art critics as well as by political activists and the masses, a perspective presented at the conference by French sociologist Nathalie Heinich.

This painting was offered to the Basque government by Picasso, but they refused it at that time. Now they want it back above all else. It is currently in the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, after about 35 years in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, following its display in New York City under the auspices of the American Artists Congress in 1939. The Congress was a leftist Popular Front group of artists who worked together on highly political exhibitions in New York City mainly in the late 1930s. For more information on that see my book, Art and Politics in the 1930s.

The fascinating fact about the Basque country with respect to Bilbao, the other focal point of the conference, is that this area of Spain has maintained its own independent treasury since the Middle Ages. Bilbao was an aging industrial city when Thomas Krens approached them about building a Guggenheim franchise there. Ever other European country that he had approached had turned him down, with good reason. They were supposed to pay for it. The Basque government accepted Krens’s offer. They did so with no consultation with local cultural actors, and particularly no consultation with the long time advocate and promoter of a contemporary art space for Bilbao, Jorge Oteiza (1908-2003).

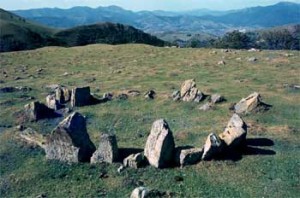

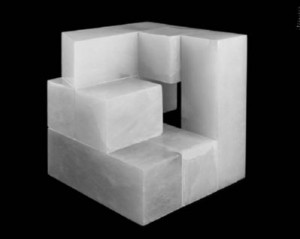

Oteiza’s story is fascinating. As a sculptor he explored new ideas about space and form in both his work and his writing. His theoretical articles follow directly on the early utopian ideas of the Russian avant-garde and predate the late modernist writings of Donald Judd. They are exactly at the point of intersectionof those two perspectives. In his writings he analyzes the pre-Columbian sculpture of the Andes, the work and ideas of El Greco, Velasquez, Goya, and Popova, Malevich, Anton Pevsner, Henry Moore, and the theater spaces of Bertolt Brecht as well as the Neolithic circular Basque cromlechs and the medieval funerary stele of the Basque country, and much more.

He makes surprising characterizations of modern art in contrast to the cromlechs: “Every work of art is either an activity of forms occupying a space, or it is space that has been emptied, disoccupied. In every formal occupation, the space in conjunction with the time of reality produces the expressive tendency . . “ (324 Oteiza’s Selected Writings)

At the same time, he pioneered a minimalist aesthetic in sculpture that won the grand prize in sculpture at the Sao Paolo biennale in 1957. His minimalist forms were geometric but open, they explore stillness, immobility, and empty space.

Then, dramatically, he gave up making sculpture. As Joseba Zulaika, Director of the Center for Basque Studies, explain in the introduction to his invaluable Oteiza’s Selected Writings “Oteiza did, however, stage a second career for himself, as ambitious, conspiratorial, and influential as the first one, but now as a writer, urbanist, architect, and cultural agitator. ‘I moved from sculpture to the city.’ He would declare. “ ( 41)

Zulaika explains that it was Oteiza “the unknown artist whose visions and furies made possible the resistance to and acceptance of the Guggenheim Bilbao Museum.”

The interpretations on Oteiza as the most innovative thinker of modern Basque art history and modern theory are still multiplying. One speaker, Juan Arana, spoke of him as practicing “revolutionary artistic sacrifice” in contrast to the Bilbao which was “totalitarian artistic entertainment,” a thesis that was argued by several members of the audience.

Prominent artist and critic Txomin Badiola gave an articulate overview of the 1980s in Bilbao, particularly the New Basque Sculpture, of which he was a member as a young artist. Their action “mimicking the forms of violence” in removing Oteiza’s Homage to Malevich from the Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts and giving it to the town of Bilbao was rendered irrelevant as these young artists were confronted by the very real violence from 1984 by the ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna Basque Homeland and Freedom) separatist movement. Txomin describes walking through burning barricades, surrounded by violence between police and workers.

The New Basque Sculpture only lasted for four years, but the workshop of Arteleku provided a focal point for intense exchange of discussion. It continues to the present.

Aranzuzu

Another perspective on the topic of the conference was provided by Adelina Moya and Jesus Arpal, an art historian and a professor of Philosophy and Sociology, who contrasted Aranzazu with the Bilbao as centers for Basque culture. Aranzazu is a Jesuit Sanctuary which during the years of 1950s and 1960s provided major commissions for contemporary artists, architects and painters in the midst of the reactionary and oppressive environment of both Franco’s Spain and the reactionary Catholic Church. Some of the sculpture was censored.

But this center and the artists who worked there led in the 1960s to a new awareness of Basque art and its roots and stimulated many major artists including Chillida.

The talk contrasted this organic patronage to the implanting of the Guggenheim Bilbao in the Basque country, but subsequently the Guggenheim did begin a program of exhibiting Basque art that continues to the present day.

Yet another perspective on Basque culture was offered by Zoe Bray who discussed an art center in French Basque country called Haize Berri, (“new wind”) in the village of Izura in the Pays Basque of Southern France. This small grass roots cultural center lasted for an amazing thirty years until 2009.

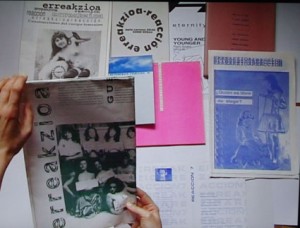

There were two speakers on Feminism, the artist Azucena Vietes, founder of a feminist art group called Erreakzioa-Reaccion in 1994.

She is a conceptual artist who recently held an exhibition at the Reina Sofia in Madrid. Azucena creates activist, feminist, queer projects, as well as workshops with children.

Erreakzioa- Reaccion has published magazines, zines, videos, and other records of the work of feminist artists both in Spain and in a feminist network that reaches internationally.

Zabier Arakistain (Arakis) spoke of Montehermoso a feminist institution that he helped to organize from 2008 – 2011. He identified himself as a feminist curator and art critic. This center showed the work of women artists, with a focus on feminist ideological development. It was the center of lively intellectual debates.

Aimar Arriola, a young curator and researcher, spoke of Pepe Espaliu, an avant garde artist who participated in various collective activities in the 1990s, and who died of AIDS in 1993. Arriola is rethinking the usual framing of his identity as the public face of AIDS through his work in the recently available artists’ archives.

This small area of Europe has an astonishingly compelling and unique history. Its cultural vitality reaches back centuries and continues to the present day. The language of the Basque country, called Euskara, is the last remaining language of pre Indo European languages. Its origins have never been known. The Basque area remains a rich cultural area, stimulated by the Bilbao Guggenheim, as well as the many cultural communities. Badiola emphasized that the sense of community continues to the present day.

This entry was posted on May 15, 2013 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Feminism, Uncategorized.

Out [o] Fashion at the Henry Art Gallery

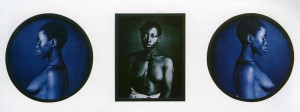

Carrie Mae Weems Sea Island Series

“Out [o] Fashion: Embracing Beauty” at the Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, changes the way we see photographs. That is a big statement! But it is really true. The very title disrupts us before we even see the show, that missing “f,” those brackets! What does it mean? It means that we can’t assume fashion or beauty as fixed ideas, but as subjective constructs embedded in social contexts. After seeing this show I saw familiar images as if for the first time, and unfamiliar images with sharpened insights about the ways in which photography constructs beauty. A photograph is a dialogue between the photographer and the subject. It is also a conversation with a viewer. Even in cases of ethnographic images, in which the subject would seem to be simply a category, we could see oppressive constructs subverted by a self-aware subject.

Professor Deborah Willis, eminent artist, art historian, New York University Tisch School of the Arts, Professor, and MacArthur “Genius” Award Recipient, curated this provocative exhibition as the first resident scholar at the Henry Art Gallery, a wonderful idea initiated by Henry Art Gallery Director Sylvia Wolf. Professor Willis selected the exhibition from the extensive photography collection at the Henry that extends from the 1860s to the present, as well as from the Special Collections of the University of Washington Libraries. She spoke of how unusual the collections were because of their inclusiveness, particularly of both studio and commercial photography, apparently not a usual approach in collections on the East Coast.

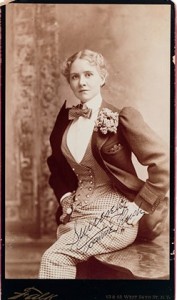

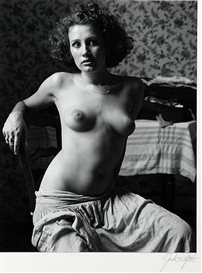

One of my favorite examples of commercial photography was Benjamin Falk’s Portrait of Miss Rush, the Actress, (1892/1897) actually a cigar advertisement, but the elegant actress in her three piece male attire complete with bow tie, all in contrasting patterns, stuns us with her aplomb. She eyes us directly. In the catalog that photograph is provocatively juxtaposed to Jack Welpott’s Sabine, Arles France (1973), a photograph of a half-clothed prostitute who looks off to one side, much less sure of her place in the world. There are many examples of such juxtapositions, as well as multiple perspectives on one subject, such as the prostitute (of which there are three photographs that are wildly different).

The exhibition is divided into three themes, “Imagined Identities,” “Fashioning the Body,” and the “Speculative Pose.” In the very first gallery we are immediately confronted by Carrie Mae Weems’ work based on 1850s daguerreotypes of slaves. The slave has been stripped to the waist (like Sabine above, also pointing to sexual domination) but here the lacerations of slavery scar the breasts. When commissioned by Louis Agassiz, the famous professor of Natural History, the intent was to create dehumanized specimens. Weems has enlarged, reframed and developed the original photographs adding in this example, a blue tonality and two profiles. In the process we see this woman as a victim, and as a record of brutality, but also as a survivor whom we honor. (Carrie Mae Weems has a major retrospective exhibition that includes the series from which this work comes, Sea Islands (1992) at the Portland Art Museum until May 19.) Clearly, both the original photograph and Weems reinterpretation, as well as our own responses, are all “imagined identities.”

Willis catalyzes that dialog in her exhibition as well as in the catalog. Near the Weems’ photograph in the exhibition is a work by Edward Curtis, not of a native American, but of an African American woman whom he has dressed up (her breasts barely covered) and called African Queen (1898)! Nearby, photographs of Native Americans also surprise us. Fred E. Miller, who worked at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, married a half-Shawnee woman and was known as a friend of the Crow, took sensitive images like Crow Woman (1898/1912 printed 1985), a profile of a young woman in a patterned dress with long hair streaming down her back.

The second gallery of the exhibition “Fashioning the Body” again includes work by well known photographers, like Diane Arbus and Cindy Sherman, next to lesser known works like the surprising book art of Tamar R.Stone, Dress versus Woman (Plain Words for Plain People 2008). Stone embroidered in a small book and on an actual whalebone corset an amusing and also astonishing commentary on fashioning the body. The corset, of course, forced the body into dangerous constrictions of the internal organs. (The violence of foot binding is a parallel example of painful shaping for the sake of beauty, although that was not represented in the exhibition).

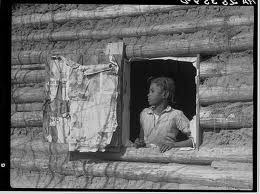

The biggest surprises for me, though, were the ways in which the exhibition enabled new seeing of familiar images, particularly in the third section “The Speculative Pose.” About Dorothea Lange’s “Waiting for the Relief Checks at Calipatria, California (1937), Professor Willis commented on how these men had put on hats and jackets to maintain self-esteem as they stood in line. About another Depression era photograph by Arthur Rothstein, Girl at Gees Bend (1937), she pointed out the contrast of this young girl’s poverty framed in a log cabin window to the image in the newspaper of a glamorous white woman that would face her inside when the window closed.

© Arthur Rothstein Girl at Gees Bend, 1937 on exhibit in Out [o’] Fashion, at the Henry Art Gallery. This image was taken as part of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) project in the 1930s.

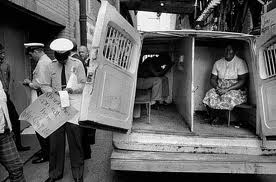

Willis’ analysis of Bruce Davidson’s Black Americans (1963), from the Civil Rights era opened up layers of seeing. An arrested protestor, dressed in a flowered skirt and white blouse sits inside a police van; she is framed by its small compartment (her head reaches the roof). Her hands are folded in her lap and her eyes are looking outside the van to the right, away from the police, toward freedom. The door has not closed on her yet. At the left of the van, a policeman holds her sign, “Khrushchev can eat here Why Can’t We?” This extraordinary moment of capture and resistance, all contained in the woman’s calm posture, speaks volumes about the individual actions that led to massive change in the United States during the Civil Rights movement.

© Bruce Davidson Black Americans 1963 from the series “Time of Change: Civil Rights, 1961- 1965” on exhibit in Out [O’] Fashion, Henry Art Gallery

Another familiar artist, Lisette Model, is represented by Famous Gambler, Nice (1934 printed 1977). A large, well-dressed woman sits with her back to us on a verandah, a pot of tea in front of her. We experience in that wide back (her face is obscured) an enormous strength and presence. In spite of the cane that leans against a nearby chair, we know she is a woman who is confidently acting out her self-fashioned identity. Model is well known for her clandestine close ups in 1930s Nice; in this photograph, her subject dominates the photograph entirely.

Go and see this show and enjoy the famous artists (Weegee, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Imogen Cunningham, Marsha Burns, Irving Penn, Cindy Sherman, Lewis Hines), the famous people (Frederick Douglass, Robert Mapplethorpe, Bella Abzug, Martha Graham, Andy Warhol), even the contrived photograph of a traditional beauty (Cecil Beaton’s Marlene Dietrich).

Look at the details and you will start thinking in entirely new ways about photography, image making, construction of identity. Buy the catalog and think some more; it is a second exhibition: The ultra elegant Lady Diana Cooper by Cecil Beaton is opposite the African Queen by Edward Curtis in the catalog.

Deborah Willis has led us into a carefully cultivated garden of images that open up a world of possibilities for thinking about how we perceive beauty, how we perceive others, and how we frame ourselves. Nothing is “Out [O] Fashion” here.

This entry was posted on April 6, 2013 and is filed under Arican American history, Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism.

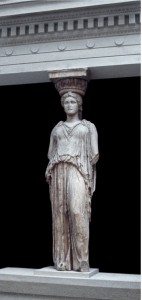

Contemporary Art and Archeology in the Middle East: Crying Caryatids, Flooded Histories, Graffiti, and Puppet Shows

inside the ancient bridge at Hasankeyf

Contemporary art and even the study of archaeology in the Middle East are deeply embedded in the dramatic economic pressures and political stress in that part of the world.

To start with the most surprising topic, contemporary study of archaeology as a practice, “Indigenous Archaelogies of Ottoman Anatolia: Decolonizing Spolia” presented at the College Art Association Conference by Benjamin Anderson of Cornell University was a clearly argued lecture calling for consideration of the indigenous point of view on archaeological objects and sites, not just the interests of economic and intellectual elites.

A current example is the battle to save Hasankeyf (above) on the Tigris River, about to be flooded by a new dam along with 600 other sites on the Tigris. In 2009 there was a big effort to make it a World Heritage site, but the Turkish government refused to support it. The village has been an active settlement for 12,000 years. Below we see the villagers protesting the plans to flood it. The dam is built though and the floodgates will open any day. It is part of the GAP project, the massive Eastern Anatolian development that is meant to make Turkey energy independent ( while it destroys history, cultures, massive tourist destinations and natural habitats for rare animals.)

Spolia is the re-use of archaeological remnants in later architecture, but its roots are in the word “spoils” based in the Italian word, “spogliare” to strip. Archaeological spolia enter a second history when they are part of a new fabric; in some cases they have a spiritual or even mythic meaning to local people entirely different from the original significance of the work.

According to Ben Anderson’s recounting, it is told that people heard the caryatid maidens from the Parthenon cry as one of their sisters was removed by Lord Elgin!

In the removal of ancient sculptures from sites there is frequently (even today) collusion between elites, archaeologists and the government, and a complete disregard of the feelings of the people in a local community where the object is embedded.

The removal of pieces to European museums was rampant in the 19th century. Apparently the first law to prevent this was passed in 1869. We are all familiar with the ongoing repatriation campaign particularly for the return of the Elgin Marbles to the Acropolis Museum. Now we have another reason for them to return: the crying maidens and maybe the grieving gods of the tympana as well. But no amount of crying is going to survive the drowning about to happen at Hasankeyf.

“Submerged Stories on the Sidelines of Science” a presentation by Laurent Dissard at the University of California, Berkeley, also talked about the “others” of archaeology, in this case people living at the site of what became the Keban Dam on the Euphrates River, built between the 1964 and 1977 in Eastern Anatolia. As teams of archaeologists came to rescue sites about to be submerged, they paid scant attention to the local people who lived and worked the land in the villages near the dam (162 villages and 50 hamlets were flooded). These people did not own their land so they received no compensation. They lost everything, but they are barely mentioned in reports and barely visible in the photographs. These are the “marginalized others” such as Kurds, Armenians, and Alevis that Dissard attempts to bring back to life from their erasure.

And of course his thesis relates directly to the situation at Hasenkeyf where dozens of marginalized histories are being destroyed in order to deliver power to the center (both literally and metaphorically)

“A Revolution in Art? The Arab Uprisings and Artistic Production” presented by the Association for Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World, Iran and Turkey (AMCA) at the College Art Association was also full of dramatic revelations, particularly about revolution graffiti in Libya and Egypt.

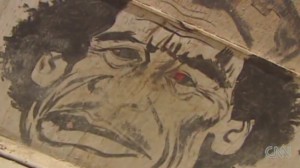

In her talk “’King of Kings of Africa’: Racializing Gaddafi in the Visual Output of the 2011 Libyan Revolution” Professor Christiane Gruber of the University of Michigan, a specialist in Islamic culture,

spoke of a particular type of street graffiti. the street imagery specifically in Benghazi, where African mercenaries (Tuareg from Mali who have been revolutionaries for decades in their own country) killed many Benghazis as part of Gaddafi’s mercenary forces.

Gaddafi was a big financial supporter of various countries in Africa and was elected President of the African Union of 53 states in 2009. He had been proposing a United States of Africa as a way to stability (one wonders if this is why we were so eager to do him in). In 2008, 200 African Kings endowed him with the title of “King of Kings” of Africa in Benghazi. He declared “We want an African military to defend Africa, we want a single African currency, we want one African passport to travel within Africa.” Kings all dressed in traditional royal clothing and gold crowns came from all over the continent, including Mozambique, South Africa, Ivory Coast and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

During the Revolution, Benghazi cartoonists, particularly the artist Qays al-Hilali, poured out their anger at the oppressive society in Libya. Qays transformed Gaddafi from the King of Kings to the “Monkey of all Monkeys.” (I did not find those images available online)

The monkey in local culture, according to Gruber, is a sycophant, hypocrite and trickster, as well as representing cunning. She pointed out that the language of the cartoons’ epithets was a street Arabic specific to Benghazi.

The caricatures emphasize his afro hair and “ape-like” feature. Qays al Hilali was killed during the uprising, intentionally it would seem, because of his explicit cartoons.

Although there has been a flowering of murals in many places in Libya, only in Benghazi is are the references so explicitly targetting Gaddafi as “King of Kings.”

Professor Gruber concluded her presentation by providing analytic tools for thinking about what she called “conflict aesthetics”. The concepts she listed were incongruity, metaphor, stereotypes, and turning the morally objectionable into a joke. These works she said violated predictable conceptual patterns. These are definately concepts to think over. Very few people ( including myself) take a step back from street art to try to analyze it aesthetically.

Jennifer Pruitt speaking on “Painted Discontent: The Role of Street Art in the Egyptian Revolution” discussed the changing dynamic of street art over the course of the uprising in 2011 as murals were created, altered, painted, over, effectively switching sides day by day. Martyr paintings were vandalized by pro Mubarek forces, then repainted.

Ganzeer is by far the best known of those artists. He has even been featured in Art in America as part of “The New Realism.” He painted 18 martyr portraits, some of them viewable online with a map to locate them at cairostreetart.com

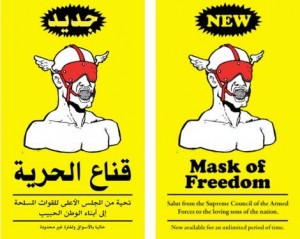

He plastered this ironic and frightening image around Cairo at the height of the uprising.

Ganzeer here is painting one of his most famous murals. Below is the full mural, the encounter of the tank and the bicycle with the person carrying bread. It was later painted with streams of blood under the wheels, as well as being painted out. But much graffiti survives online. This virtual catalog is invaluable as a record of the specific images and sometimes their changing conditions.

The tank and the bicycle. Note the sad panda ( the artist called himself Sad Panda) on the far right by a different artist. This mural went through many repaintings,echoing the power struggle in the streets

Last night, at the University of Washington, I heard a third talk on culture in the midst of uprising: “Ideology and Humor in Dark Times Notes from Syria, Memos to the President,” by Professor Lisa Wedeen sponsored by the Jackson School at the University of Washington. Her main theme was that a neoliberal autocracy and consumer culture had created an affluent culture in Damascus and Aleppo that had little interest in the uprising initially. Neoliberalism created sites and images that constructed and served a wealthy society of privilege. And, the people killing the revolutionaries, the “regime thugs” were frequently hired by Assad from low income areas. The privileged said, according to Professor Wedeen, “It will resolve itself.”

As the situation worsened, the youth of the privileged joined the uprisings, and of course, today, nobody can ignore it any longer. The battle has been taken directly to Aleppo and Damascus. We heard about certain popular culture soap operas like “A Forgotten Village” actually supported by the regime even as it was making jokes about the surveillance society. These consumer oriented products of entertainment were examples of pressure valves organized by the regime. So they stood in a complicit relationship to the Assad government.

Such a situation of co-opting a critical voice has a long tradition in Syria as pointed out by miriam cooke (She writes her name in a lower case) in Dissident Syria, making oppositional arts official, Cooke discusses performance art, visual art, films, and “prison literature” as a negotiation between the State’s controls (this is under Assad’s father Hafiz), and their desire to be in opposition to its policies, while not ending up in jail. Even more complicated to think about is the idea that “the state that controlled and sometimes silenced them also needed them.” (4)

In the last two years, there are also contemporary dissident voices in Syria who are not at all part of the consumer or official culture. The puppet show “Top Goon Diaries of a Little Dictator” by the collective Massasit Matti has produced two Seasons and 17 episodes of comedic critique of the government. I would love to read an analysis of it in the context of the history of puppetry in the Middle East. Season 2, No 17 and the last episode, is chillingly pertinent, it ends with the Assad puppet placed in a coffin and the cover closed on him. This puppet show is easily viewable on You Tube. It was partially funded by money from abroad giving it a very different relationship to the regime that commercial soap operas.

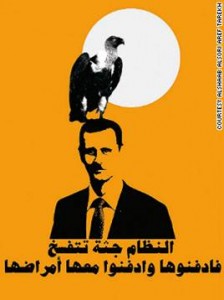

Ali Ferzhat is a famous cartoonist who was formerly supported by the regime, but now criticizes it. He was attacked by the regime, some of his fingers were cut off. He now works from outside the country. There are others as well like the poster collective that made this poster.

Culture is always embedded in politics. It can be sacred objects shipped abroad from archaeology sites by colonial elites or villages drowned under water by economic development; it can be street graffiti finally free to lampoon a hated leader in Libya or militarism in Egypt, it can be carefully crafted online videos that document protests in New York or DC, it can be theater that protests injustice in historical contexts that are still resonant, it can be writers and poets who say one thing and mean another (I remember meeting a filmmaker from Croatia who spoke of how everyone could read between the lines under socialism), it can be producers of soap operas in Syria who are protesting the government oppression with the government’s support.

It can be a blog that tries to explore all the possible ways of thinking about art and politics.

This entry was posted on February 23, 2013 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art in War, Contemporary Art.

“Idle No More” and other Protests

The massive Climate Change protest in DC brought together Indigenous leaders from Canada and the US as well as African Americans with the usually dominantly white movement. In Seattle, sadly, we had two separate demonstrations, one on Saturday and one on Sunday, the first organized by Idle No More the Canadian based Indigenous protest of violation of treaty rights-such as removal of environmental protections from hundreds of tribal lakes and lands- they have been holding huge actions all over Canada. Here in Seattle there was a demo based at Gasworks Park.

The second by the Sierra Club at Golden Gardens, a rally, photo, and short march. As far as I could see there were lots of white people (probably because of the location.) Mayor McGinn gave a speech. This is Backbone’s Snowflake nuzzling a bullet train carrying people as an alternative to coal train.

The Sierra Club rally focused heavily on the coal trains, I wish it had also officially embraced the issue of tankers with tar sands oil negotiating through Puget Sound, as well. as fracking. The tankers are already in Puget Sound, but there is a planned escalation from 5 a month to over 30 a month. The Grim Reapers got it right ( a protest in Olympia on inauguration day that I joined)They included all of the disasters.

According to Carlo Voli, climate activist, all the refineries in Washington State are already processing tar sands oil, we are already using it in our cars. I drove to the rally with much guilt ( far away from downtown core), how many fossil fuels are we using as we protest. Harpers Magazine author Richard Manning, writing on the devastation in Bakken, North Dakota from fracking for oil told us at the end of his article exactly how much fossil fuel he used to write his article. We should all be thinking that way.

A show at the Burke Museum Plastics Unwrapped manages to tell it all in a compressed space : 1500 disposable plastic water bottles used every second in the U.S., 3,000 plastic bags every quarter of a second,

170 pounds of e waste discarded every second in the U.S., 9 million pounds of marine debris removed from beaches last year.

Only 7 percent of plastics are recycled each year, ghost nets left in the ocean kill thousands of marine mammals, seabirds, fish and other creatures. On the plus side the show talked about recycling!

Of course, not using plastic in the first place is a better idea. It is impossible though. Trader Joe’s is hopeless on packaging. When buying any product think about re-use vs waste, like all cellophane (petroleum based) bags go right into the landfill, but a nice glass jar can be re used over and over. Our local Madison Market Co-Op has fantastic bulk items. I keep discovering new ones, most recently, bulk frozen peas (which unfortunately are delivered by the truckers whose strike is being smashed by Whole Foods). If you bring your own container or bag you are on a plus side with the trash problem.

So when I travel on an airplane (one trip equals driving an SUV for a whole year and I make a lot of trips), I make my tiny effort by bringing my own water bottle and tea so I don’t generate trash on the plane