Lake Atitlan, Chichicastenango, and Antigua: Dreams and Realities

Lake Atitlan is one of the most beautiful lakes in the world. It has two volcanoes perfectly situated to create a picturesque or even sublime appearance (ie, the difference between simply attractive and actually uplifting, according to 18th century English categories of landscape.)

Naturally a beautiful place like this attracts a lot of people who like beauty in the traditional sense of the word. It is kind of like the National Parks in the US, chosen for their spectacular features, like Yosemite, Yellowstone and Glacier. It makes many people happy to see this view.

But of course, that is not my particular obsession as the author of this art and politics blog. I have to look under the surface of the beautiful and see what is really there.First of all as we arrived to take the boat to our beautiful Villa Sumaya yoga retreat location we saw raw sewage running into the lake at the boat dock! Wow.

Then we learned that the lake had pollution problems: algae blooms shore to shore last year was one big problem. Also in the last year the lake water level rose dramatically flooding out houses on the shore. It is not clear whether this was simply caused by larger than usual rainfalls or blocked exits to the lake, or cosmic energy (apparently the lake is an energy nexus). But the result was a lot of people lost a lot of property into the lake.

But aside from these ecological issues, the human ecology was provocative as well. There were many gringos living along the shore ( many healers tapping into the cosmic energy, as well as hippies from the last century still there). During the Civil War the communities around the lake were decimated, almost all the men were killed. It was a dire situation, perhaps the reason why I still felt a sense of heavy sadness in the spirit of these people.

And of course poverty. The Maya mostly lived up higher on the hills surrounding the lake. The shore is the lusher area, obviously more accessible and inviting. Further up the land is really steep and dry and inhospitable, but it is there that Maya are trying to farm. We didn’t see a lot of terracing, but we did see fields planted and growing. There were exceptions to this struggling life though.

We visited San Juan La Laguna, a dymanic, proud and very clean community along the lake. It had an art cooperative, murals on many walls along the street, a women’s textile cooperative using only botanical dies to create amazing fabrics, a coffee cooperative producing shade grown coffee that is very sweet because it is grown in lower elevations (up higher the coffee gets more acid). There was a medicinal plant center, and a thriving school. We saw a center for women who are victims of violence. We took a little Tut Tut around that was really fun, with an educated driver who said he was a software engineer making a little extra money.

So that was all positive.

There are more pictures on my flikr site. and here.

But then as we went around on the public boat we saw very very young girls with babies, some of the babies looking sickly. Apparently the teenage pregnancy rate here is really high, partly because of fundamentalist missionary groups who ban discussion of contraception.

But again, there are groups who are trying to make the situation better like the Amigos de Santa Cruz, who emphasize education and training for youth to enable them to have a better life. It was founded 14 years ago and they are still going strong.

Villa Sumaya where we had our sojourn in paradise at a yoga workshop is committed to this program as well as employing many local residents at the villa itself. As we worked at warrior 2 and downward dog, they cleaned the pool and served the meals. It felt pretty colonial actually, but then we couldn’t avoid the reality of being incredibly privileged, fortunate people.

Villa Sumaya is also committed to ecological balance and they had a great program that they participated in for non recyclables. We stuffed them in a plastic bottle, and the bottles became material for building. I loved that, as the trash that we generate every day is one of my obsessions.

One day we went to the market in Chichicastenanga. It was absolutely overwhelming, hundreds of textiles for sale. And lots of amazing artisanal pieces like bracelets and key chains made of beads. Apparently beadwork was introduced to the women in this area during the depths of the Civil War in the 1980s. The sense of color was fabulous.

Chichi, as it is known, was also the center of Maya history: nearby many of the events narrated in the Popol Vuh, creation story of the Maya, took place. Even today, the Maya come in from the hills and practice their own religious rituals right in the middle of the Catholic Church. This is a wonderful sharing of beliefs, the result of a priest who at some point started reading the Popol Vuh in the church. More images on flikr.

Finally, we went to Antigua which was in the midst of holy week processions. Immensely heavy larger than life carved realistic figures of Christ, Mary, Joseph etc, were carried through the city by 100s of people (sometimes children) for many hours, clearly as an act of penitence. But at the same time there was a festive atmosphere of food, balloons, and a general sense of excitement. Antigua is the old colonial capitol which had lots of ruined churches because it has been leveled by earthquakes over and over. Most of the buildings today are one story. There were tours of the ruined churches with stories of episodes like nuns being shut off from the world entirely. Today they are often used for weddings.

During our brief visit to Guatemala we met many, many people on “missions”, for a week or two or six weeks. Lots of US people down there doing a project to make life easier for the Guatemalan people, many but not all were religiously affiliated. Of course, life would be a lot easier for them if we just quit being a military bully there. Legalizing the passage of drugs would free up money for education, health care and other good things.

This entry was posted on May 4, 2012 and is filed under Guatemala.

Tikal A Few Thoughts by a Non Specialist

Tikal. Thousands of unexcavated sites, but Temple I, the icon of Guatemala, does not disappoint. A “mortuary pyramid” not a temple, it is elegant, grand, and spectacular. Pretty much invisible today is the seated sculpture of Jasaw Chan K’awiil on the top.( 734AD). It was first discovered in 1882 by Alfred Maudsley. The king was buried underneath with an enormous collection of jade, mirrors, pearls ceramics, and other objects including intricately incised bones. Today we can climb wooden stairs up some of the structures ( this is Temple II) , not the challenging steep stone steps.

Tikal, one of the great mesoamerican sites in Central America, still emerges from deep jungle in the lowlands of Northern Guatemala. It is at the center of a large biosphere, but actually a lot has been clear cut (Various Europeans starting in the 1890s : the British logged for mahogany. The sites emerged as the logging occurred.) This jungle biosphere is the home to 60,000 people. Five days walk through the jungle would have taken us to El Mirador, another huge site. Next time!

We stayed at the Tikal Inn at the site, an amazingly beautiful little hotel, with a swimming pool, and comfortable rooms. We felt really decadent, compared to previous visitors as recently as the 1990s, while the Civil War was still going on and the government was not able to have the luxury of catering to tourists. Although we had electricity for only two hours, we never missed it.

Right at the lodge were all sorts of beautiful birds, like this oscellated turkey,and it was easy to walk to the site.

We took several tours with guides,all of them well-informed on various topics, history, geology, ecology, birds, engineering, religion, dating systems. Here is a guide pointing out the dating system on an onsite stele.

The most exciting tour was getting up at 4am to walk through the darkness and hear the jungle awaken from the top of Temple IV. It started with a single howler monkey, then a conversation between them, then the birds began, first a single one and then a chorus of many different birdsongs. I am a novice birder, but they were whistle like, sharply repeated, and some faster some slower. In the background the howlers continued, like the bass in an orchestra. The original music. As the mist lifted, the monkeys subsided and the birds got more varied and louder.According to one expert guide, there are 400 species of birds here, including 65 migrating birds. I saw about 20 including the Toucan, known as a flying banana because of his big yellow beak and the Red Lored Parrot.

Apparently quite recently the howler monkeys were almost extinct, according to a guidebook written in the late 1980s.

The small coatimundi was everywhere, an anteater like small creature which had the run of the site as soon as the people left.( I think they may be overbreeding).

We also saw leafcutter ants who have an extraordinary division of labor.

By far the best experience was spending a day in the jungle exploring, Temple VI: I was helped up by a steel armed worker for the National Park. Above another Park employee is taking a picture of the big rain god mask on the upper part of the temple.

Then Complex G, an amazing complex of buildings with lots of corbelled arches.

and the Central Acropolis where one of the excavators, Teobert Maler, set himself up from 1895 – 1904. It is a multi courted series of buildings on different levels and with many plans. Fascinating to explore. This photograph doesn’t tell you much.

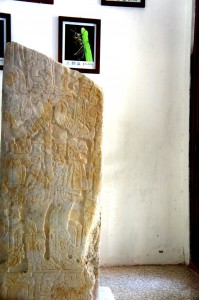

The central area of Tikal has about 200 stone monuments including stele and altars. Most of them are now in the two on site museums, one called the Ceramic Museum, the other the Stone Museum, although the Ceramic museum also has Stele including the most famous no 31. This photograph is pretty impossible to see

(taken illegally), but it represents the ruler Siyaj Chan K’awiil ( Sky Born K’awiil) 411- 456 AD flanked by portraits of his father Yax Nuun Ayiin with enormously complex symbolic regalia. and a representation of him in the headress emerging from a split in the sky.

Altar no 5 was in the Stone Museum, and a painting of it was on the wall of our hotel dining room. Two rulers Jasaw Chan K’awiil and another leader are conducting an exhumation ritual with the bones of a high ranking lady between them.

An amazing item in the Stone Museum, aside from the many stelae, was a wooden lintel from Temple 4 ( I think it is a replica). There were a lot of wooden lintels on these temples, many of which have been taken off to museums in Europe, with amazingly intricate representations of various rulers. Many more objects from burials are also to be found in the National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (the old guidebook I have written by William Coe of the University of Pennsylvania mentions several jade pieces stolen from the Tikal museum in 1981).

Apparently the site was occupied and temples and other structures were built over a period of 1100 years. Starting in the Preclassic which is about 600 BC, then a Classic Period 250-900 and the Post Classic. Most of the structures date from 550 – 900, the so called Late Classic, but underneath the visible structures are layers of earlier buildings, as well as burials. Under Temple I the burial had 8 kilos of jade objects.

The construction of Temple I appeared in a model at the Popol Vuh museum.

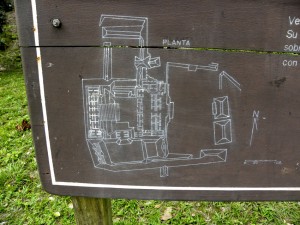

Leverage and ropes were used to move the colossal blocks (exactly the same system was used for the John T. Williams commemorative totem pole raised in Seattle Center in 2012.) Who were the laborers? Were they devout, were they slaves? Who were the designers, the engineers? It was evident as we visited the site, that the Maya were brilliant engineers, particularly with stone buildings and organizing water supplies. This sign suggested the complexity of underground tunnels used for transporting water.

They separated fresh water supplies in various categories.

The technique of making quick lime to hold the stones together was also explained, difficult and time consuming. We saw kilns that survived as well as underground storage areas for chocolate, maize and nuts. Human waste was used as fertilizer.

The so called “Mundo Perdido” had several amazing structures. East of its main pyramid are three smaller structures that serve to mark the point on the horizon where the sun rises on the solstices and equinoxes. Behind us is one of the pyramids that show the influence of Teotihuacan design.

The surviving (all but 4 destroyed by the Spaniards) codices from the Maya contain predictions and knowledge about planting, weather, and cyclical patterns that relate to the purpose of the “Mundo Perdido.”

We tried to imagine how Tikal would have looked, swarming with people and the temples brightly painted.The sculptures showed clear evidence of the arrival of people from Teotihuacan in the design and the sculpture (and representations of Tlaloc, the rain god, who is all over Teotihuacan).

They arrived in 389 AD according to new understanding of the dating system. Thus much of what we see at Tikal is a blend of Mexicana and Maya styles. And of course we are looking at the culture of the elites. There were many ordinary houses, but they have all disappeared. Apparently they dispersed into small communities in the jungle when the large city complex fell, but today there is still an active sacred alter near Temple I in the Central Plaza.

One theory of the decline of Tikal as a grand empire center is that there just wasn’t enough land to cultivate or water to support the population as it expanded. But the decline was also probably because of warfare among different Maya, just as today, we are squandering our resources on warfare and despoiling the environment. But what will be left of our culture in a thousand years ? Maybe piles of rusted military equipment that accidentally survives.

According to one guide (on Temple IV at dawn) these temples had small chambers in which elites ate magic mushrooms and snorted various leaves that made them very high a lot of the time.

And of course the Maya survive until today, despite all the efforts to obliterate them and ongoing taking of their land (see previous post). The elegance and dignity of the people is remarkable given what they have been through over the centuries. According to the National Museum of Archeology brochure there are 24 different ethnic Maya groups in Guatemala today. But it declared “Guatemaltecos somos todos.” Creativity wins!

This entry was posted on May 3, 2012 and is filed under Guatemala.

My May 1st

I arrived at Westlake around noon on May 1, the sun was shining. Youth Speaks was performing amazing songs and dancers were breakdancing on the concrete spontaneously. It was a joyful sense of celebrating creativity, resistance, and talent. I was particularly thrilled with the voice of a young man named Lorenzo. The sign behind the dancer says “Decolonize”

I arrived at Westlake around noon on May 1, the sun was shining. Youth Speaks was performing amazing songs and dancers were breakdancing on the concrete spontaneously. It was a joyful sense of celebrating creativity, resistance, and talent. I was particularly thrilled with the voice of a young man named Lorenzo. The sign behind the dancer says “Decolonize”

I was surprised there weren’t more people there. Suddenly a lot of people arrived who had been marching a few blocks through downtown. The change of mood was immediate. They looked shaken and angry. A man on the stage spoke of what had just happened, but the group was still going forward with the demo. One friend I talked to said, oh yes some tear gas. But I felt the sense of dark anger. Later I learned that as I was enjoying creative expression in Westlake, the “black bloc” had broken windows and aroused the police to tear gas. Who is this black bloc???? Supposedly they are “anarchists” but the anarchists I talked to said they had nothing planned like that. Are they skinheads mascarading as anarchists??? It certainly seemed like that, in spite of their “anarchist websites” sited in the paper.

The result was anger among the other marchers, but certainly their spirit was not broken at all. The Occupy will continue to be non violent. I was impressed that the news media actually distinguished these people as vandals that weren’t from Occupy

So then I went onto the immigrant rights march which started at Judkins Park at 5PM. I went with a young woman who is out on bail from detention, having been held because of an expired license. Her family managed to raise the enormous sum of $5000. And she was reunited with her small daughter after three weeks, but deportation hangs over her head if the police decide to question her for any reason at all. She doesn’t even have to have done anything. She was told to stay at home. She can’t work because she doesn’t have a work permit (which she is trying to get). They took away her drivers license, so she can’t drive. Veracruz, where members of her family live, is riddled with gangs, and incredibly dangerous. She has lost cousins who have been murdered.

We looked for groups at the march who might be interested in her situation (she is fortunate to have legal help also). She wants to be public about it, which is incredibly brave. All of a sudden the march was very real. It was a protest, but also a lot of people fighting for a life with work, family, and hope for a future. Simple ideas. Simple hopes. But in the last few years, the immigrant situation has deteriorated severely. Deportation has escalated . 46,000 people were deported last year who have US children.

The mood of this march compared to the first one I went to in 2006 was somber, resistant to giving in, full of chants “the people united can never be defeated.” It was large, several blocks long.

When we reached downtown on Union street and headed west toward the federal building, a huge crowd joined us! It doubled the size of the march. Probably they were from #Occupy and the Westlake area? It was exciting even as it started to pour down rain.

Unfortunately the news was dominated by the “state of siege” downtown, lots of reactions, boarded up stores etc, rather than the important messages of these two groups of people: resisting corporate power, and standing up for a life free of surveillance and pursuit. But really, the people who were in these events felt the strength of numbers, felt the power of the people, and I personally felt the joy of creativity among the dancers and singers and art making that I saw at Westlake at noon.

This entry was posted on May 2, 2012 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Guatemala Part I Museums in Guatemala City

On the day we arrived in Guatemala, staying at this very pleasant hotel near the airport, President Otto Perez Molina announced that he wanted to decriminalize drugs and drug trafficking through his country. Other Latin American and Central American leaders also support reform of drug policies like President Santos of Colombia and Laura Chinchilla of Costa Rica. What a good idea!

But of course the US opposed it at the Summit of the America’s regional Latin American meeting in Cartagena Colombia, offering instead more money for “security”, our main export guns. The escalating violence in Central America and Mexico is related to the Plan Columbia that was like according to Greg Grandin, a “tsunami” just as those countries were coming out of years and years of devastating civil wars (also fueled and equipped by the US). In addition CAFTA ( Central America Free Trade Agreement) and NAFTA are destroying markets for local farmers, leading to a void filled by the drug market. Finally, as Grandin pointed out along with Ethan Nadelmann on Democracy Now, there are powerful forces in the US who benefit financially from the “drug war”.

But it gave the first day of our trip to Guatemala a positive feeling.

Two weeks after we came home we learned of a march by 15,000 campesinos and peasants who were demanding approval of bills that would protect their livelihoods from mining companies and other multinationals who were forcibly evicting them from their land and having protestors arrested.

So against those two bookends I will speak of our trip to Guatemala which was intended as a break from my continuous exploration of art and politics. I went there for the unusual purpose of a Yoga Workshop on Lake Atitlan with my exceptional instructor in Seattle, Douglas Ridings.

Before the workshop we went to five museums in Guatemala City, the Popol Vuh, a beautiful collection in a contemporary building that draws on motifs from Maya Temples, and paired with it the Textile Museum, which would loom large in our experience of Guatamala ( a fact we didn’t know on our first day). For more photos of the artwork inside the museums see my flikr site.

The next day we went to the National Museum of Archeology and Ethnology which had a mural by a modern artist in the lobby and a special exhibition about the site of Waku in Peten, School children were having a special event there also and were looking at their history.

At the National Museum of Modern Art/Carlos Merida, we saw some excellent painting and sculpture from the 20th century

and the Museum Miraflores

in the incredibly upscale Galerias Miraflores shopping mall which is on part of the site of the ancient city of Kaminaljuyu that thrived for almost 2000 years.

All of these museums were beautifully installed and full of information about Mayan culture. Popol Vuh (named after the Mayan Creation Story) included artifacts from two underwater sites from the bottom of Lake Atitlan and the nearby Lake Amatitlan.

The Textile Museum next to the Popol Vuh traced the history of textiles back to 5000 B.C. and the development of the back strap loom, still in use today. The Spaniards introduced sheep wool, silk and linen, and in the end of the nineteenth century chemical dyes were introduced.

Many changes have occurred since the 1970s including machine made embroidery, and the use of synthetic fabrics like rayon, but as we witnessed, the textile tradition today in Guatemala is still thriving.

Textile patterns are symbolic, one of the reasons the Spaniards feared this art expression. That may explain why in contemporary fabrics the arrangement of colors is always random as is the repetition of patterns. A motif is always varied by size, color, and other small details. But the sense of color is stunning. The basis of the colors is in botanical colors from plants, but the desire to create these beautiful textiles is an inherent aspect of Mayan culture for centuries (in neighboring Honduras everything is black and white) . It is wonderful to see these traditions still thriving after so many years of slaughter in the 20th century and during the years of Spaniard rule.

The countering of violence with art is stark in Guatemala.

The National Museum of Modern Art reflected the region’s deep roots in brilliant colors and abstract patterns: artists were making extraordinary sculptures and paintings in the modernist tradition throughout the 20th century. The best known is of course Carlos Merida,

but in addition there were artists Roberto Ossaye.Calvary, from 1953 is only one of many strong paintings from this era.

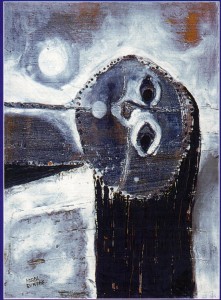

This is the work of Rodolfo Abularach The Shock 1956.

And then recent artists like Roberto Cabrera, This piece had a lot of found metal parts attached to it. It is called Transfiguration and it was created in 1969.

Efrain Recinos Grand Music 1970. The massive sculpture of wood was a combination of organ, tank and Mayan temple. I had to take the photograph on the sly and it was in the back of the museum, so the photograph doesn’t do it justice. He is a major contemporary artists in Guatemala.

Erwin Guillermo has the piece in the foreground above called Que Pasa 1951. Margot Fanjul’s crocodile with small figures on its back and in its mouth. It seemed like a Holy Week icon processional icon, but in honor of Guatemala instead of religion. But it suggested a lot of struggle.

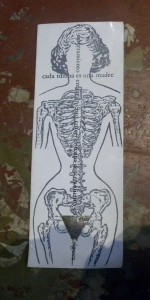

Magda Eunice Sanchez expresses the agony of the Civil War in Guatemala. Indeed Sanchez’s affecting image Girl with Her Hair in the Wind suggests the frozen fear of the ordinary person during this war that lasted from 1960 – 1996:

it killed 200,000 people, 83% Maya. 40,000 to 50,000 people disappeared and one and a half million were driven from their homes. It was later identified as a policy of genocide. Human rights violations were perpetrated particularly against women amidst the culture of violence, by Guatamalan army soldiers trained by the US. The US involvement goes back to 1953 when CIA forcibly removed Arbenz Guzman from office in 1954: from 1944 – 52 liberal economic reforms had strengthened civil and labor rights of the working class and peasants. Works in the museum suggested some of the agony of those years.

It is hard to imagine the horror of the Civil War after the horror of colonialism, slavery, slaughter. How did anyone survive. “Socialism” from 1944- 1952 was the only period when rights of the people were even considered.

And today, we have the people marching as they are being evicted from the lands by a new wave of multinational mining corporations. .

\

This entry was posted on April 30, 2012 and is filed under Guatemala.

Rabih Mroué The Pixelated Revolution

” Syrians are filming their own death” – that is how the Pixelated Revolution begins- with this text. A few images are available on this photostream. Rabih Mroué is seated on a bare stage in front of a table with a computer. A large wall looms behind him. The projection combines succinct quotes about the “rules” of pure film which he has altered to make more pertinent to Syria: “Shoot from the back and do not show faces in order to avoid recognition, pursuit and subsequent arrest by security thugs ” with live footage from cell phones held by citizen journalists in Syria that he has downloaded off the internet.

” Syrians are filming their own death” – that is how the Pixelated Revolution begins- with this text. A few images are available on this photostream. Rabih Mroué is seated on a bare stage in front of a table with a computer. A large wall looms behind him. The projection combines succinct quotes about the “rules” of pure film which he has altered to make more pertinent to Syria: “Shoot from the back and do not show faces in order to avoid recognition, pursuit and subsequent arrest by security thugs ” with live footage from cell phones held by citizen journalists in Syria that he has downloaded off the internet.

The footage is carefully selected to focus on the extraordinary fact that as Syrian citizen journalists are recording the horrible violence in Syria, they are themselves being shot and often killed. The recent case of Rami al-Sayed, who posted over 900 videos on the Syria Pioneer site His cousin Basil al-Sayed also a citizen journalist was shot and killed in late December; had been filming in Homs before he was killed, posting on the same site. The piece that Mroué focused on the most was an 83 second clip of a “double shooting”, a man holding a camera phone is filming a sniper, and then the sniper takes aim and shoots at him. We do not know if he died.

The drama of this exchange, why didn’t the photographer move away from the sniper, the fact that he must have felt invisible, although he wasn’t, the point blank shooting, are all subject of discussion in Mroué’s piece. In Beirut where it was shown there were other issues raised as well, issues also raised by Mroué’s piece shown at INIVA last spring, “On Three Posters, Reflections of a Video Performance”, only it is much more intense in The Pixelated revolution. The three posters refer to three “takes” of a suicide bomber’s video -” Reflections” are Mroué’s analysis of whether he is exploiting the videos for his own ends.

In selecting and downloading footage taken by citizen journalists in the ongoing horror of the Civil war in Syria, Mroué is doing something even more questionable according to the art critic Kaelen Wilson-Goldie:

” Should they be making art in their studios or joining protesters on the streets? Should they be agitating as artists, activists or day-to-day citizens? If artists have already been dealing with subjects such as corruption, injustice or social inequity for years, then how can they avoid having their work co-opted by the new fervor for revolutionary fare? And if they decide to take on and work through the uprisings in their art, then how can they do so without coming across as naïve, belated, opportunistic, callous or crass?

“For me these are very intriguing questions,” says Mroué, “and they’re also a kind of trap. One of the things we always say is that art needs distance, and that art needs a kind of peace. But at the same time, with the revolution in Tunisia, or the revolution in Egypt, or the violence in Syria, when are we allowed to talk about it? How long do we have to wait before we can make a work? I think there are no limits, no defined times.”

So the immediacy of these works is overpowering, and yet we see these dramatic videos in the safety of a performance space in Seattle. Is the artist making a shallow exploitation of violence? He has said that he is not an activist, he only wants to “provoke himself” not other people. So does that mean that his distance reflects neutrality, a cold intellectuality.

Definately not, it is a stance that protects him from despair and enables him to respond to a tragic ongoing nightmare in the country right next door to his own. Damascus is closer to Beirut than Portland is to Seattle. And keep in mind that civil war raged in Lebanon for a very long time, and he lived through that first hand. How would we be responding to such murder and mayhem that nearby, by fleeing, by remaining mute, by speaking? Mroué has chosen to speak, but with a formal framework loosely ( and sometimes even humorously) based on ten rules of “unvarnished cinema” the so called Dogme 95.

So the fact that he can take on Syria at all is an indication of the depth of his commitment. The use of immediate documentary is part of a now established tradition in Beirut that began during the 2006 Israeli bombardment as discussed in another Wilson-Goldie article “The War Works, Videos under Siege, Online and in the Aftermath, Again” in Art Journal Summer 2007 (apparently not available online.) But in that case it was the artists themselves as well as the citizens of Beirut who were filming their own war. In the case of Syria, Mroué is looking from the outside.

Mroué pointed out that there have been virtually no outside journalists in Syria ( that was not quite true- recently several incredibly courageous journalists smuggled themselves in and have been both shot and killed. Jon Lee Anderson has just published a piece in the New Yorker based on his courageous interviews with both sides of the conflict.

The footage that we see on syria pioneer is a lot of bombing and gunfire, as well as terrified and injured children, women, men. It is very hard to look at, hard to assimilate. So Mroué has done us a favor, he has created a distance from which we can understand and think. We are introduced to thinking about what is happening.

That is a crucial first step. Mroué has said he doesn’t “want to be a martyr for the sake of art” but the reality is that he does succeed in giving a news ignorant US audience one dimension of the nightmare that is going on for the average person in Syria. The “Syrians are filming their own death.” Very sadly, on the very day that I was writing this 13 activists were killed smuggling one photographer, Paul Conroy, out of Syria.  Paul Conroy was with Marie Colvin when she was killed in Homs.

Paul Conroy was with Marie Colvin when she was killed in Homs.

This entry was posted on February 29, 2012 and is filed under Art in War, Rabih Mroue The Pixelated Revolution.

Art in Cuba Now Part II Espacio Aglutinador

Espacio Aglutinador was founded in 1994 by Sandra Ceballos and Ezequiel Suárez. The title means a space that helps people and events come together ( a root word here is gluten) . It is the oldest ongoing independent art space in Cuba that is entirely independent of the government. Because it is a private home, events cannot be interfered with by the police.

The initial impulse for creating an art space was the censoring of an exhibition by Ezequiel Suárez called The Bauhaus Front in which the artist painted images on cardboard of various prominent people holding signs that declared for example “ The Museum of Fine Arts is shit.” It was an act of defiance against the official art venues in Havana. This Dada spirit of the Bauhaus inspired many multimedia events and exhibitions in Espacio.

The spirit of defiance and revolution against expected actions persisted inside this intimate space, even as outside the strange fluctuations of oppressions, contradictions, and successes abroad for Cuban artists continued.The social interaction is intense and powerful.

From the beginning, major critics Orlando Hernandez, Gerardo Mosquera, and Eugenio Valdes Figueroa, to name only three, have been writing catalogs and articles about the Espacio.

Espacio Aglutinador has created more than 90 events in collaboration with various artists and collectives. Many of these artists are now famous, and often the work they showed in this space was fundamental to their later fame or brought them out of eclipse.

The main principle is that it is a space that welcomes everyone, it is democratic, including young and old, trained and untrained, famous and undiscovered, living and dead. “It is a cultural space, nor a boutique, nor a foundation. It does not intend to be elitist or avangardist, populist or backward looking. … It is not a project, nor is it a beautiful idea on paper. ..Aglutinador is an event… The possibilities for error are infinite.” The artists that were shown there in the 1990s were chosen by Sandra Ceballos and Ezequiel Suárez. Some of them had been neglected, some had been censored, some were simply artists that they admired including US based Ana Mendieta and Coco Fusco.

One example is Angel Delgado who was actually put in prison because he did a performance piece in an exhibition called “The Sculptural Object” in which he defecated in one of the galleries on a copy of the Communist newspaper Granma. He was put in prison for six months: he took everything he had used while in prison in a wooden box, including 102 drawings and stories and sculptures of soap, drawings on hankerchiefs (techniques learned from other prisoners), and opened it for the first time for an exhibition at the Espacio Aglutinador in 1996. Orlando Hernandez wrote asking for his pardon: “ I see in your exhibition not only a harrowing testimony to your sadness, of your revulsion, . . . but also our own shamelessness, our weakness, and guilt.” The postscript to this work is discussed on this blog, in which the writer declares that Delgado has made a successful career from this work inpsired by prisoners media, without ever taking up there cause himself.

Another artist who had an installation there was Tania Bruguera. Her performance piece Cabeza Abajo in late 1996 included 20 participants who lay on the floor tied up. The artist as a ghost like figure walks over them, suggesting oppression, the experience of collective death, a ritual landscape full of sacrificed ideals.

By 2000, as the Cuban art scene was rapidly changing, Eugenio Valdes Figueroa wrote “ in the midst of the tensions provoked by censorship on the Island, Aglutinador offers a space for projects that have little possibility to satisfy the commercial trends stimulated by the demand for Cuban art from the outside. . . Amidst the proliferation of easily saleable formulas . . . and banal themes . . . “ it was an institution that spoke to forbidden themes and mined the uncertainties of local themes. (Espacio Aglutinador 1994 – 2004,un lugar de emergencia, p 62). Starting in 2003, a second phase of Espacio began that was even more revolutionary, without curators, without any restrictions.

One example was the exhibition “Curators Go Home” which included the piece on censorship by Celia/Yunior and friends described in my previous blog. That piece can still be seen in the Espacio Aglutinador drawn on the wall behind the work of other artists.

Sandra Ceballos, the ongoing director of Espacio Aglutinador, is a radical both in her life and in her art. She attended the Academia de San Alejandro in the early 1980s, a productive period of Cuban art, but she herself was defiant and feisty of art school norms and was expelled for behaving as an existentialist, not a worker.

But she went back and graduated, but chose not to attend the Istituto Superior de Arte (ISA). In the early 1990s she received a prestigious prize for her art and was given a one person show, but she chose once again to be defiant and showed radical feminist body art.

She has said that her ongoing radical activities and art have barred her from showing at any government sponsored spaces, and the one work by her in the National Museum is not on display.

She has worked in series, one series was focused on the fragility of human existence, the limits of our mortality in a hospital environment, another series is about the fanaticism of ideology using Fidel’s speeches as a point of departure which she wrote down frantically as though demented. Her discussion of her work and her space are on this excellent video interview. In one amusing comment she describes the space as a send up of the pomposity and seriousness of the Museum of Fine Arts in Havana. In her small house, the art is shown in the kitchen, in the garden, even in the bathroom, as well as the tiny living room.

Two other examples of radical artists who showed in Espacio Aglutinador are Colette Rodriguez and Carlos Garaicoa. Rodriguez’s work was described as hyperrealist and the catalog that accompanied her exhibition had a triangle of what people thought was pot attached to it.

Carlos Garaicoa created a series of conceptual diptychs of crumbling Havana buildings paired with austere pyramids, invoking the Tower of Babel in his title. Such an analogy was particularly apt for the strange contradictory environment of Havana, full of principles in the air, and disappointment on the ground.

Ceballos continues to sponsor radical art collaboration and events at Espacio Aglutinador. It is an incredibly important place for Cuban art as both a concept of absolute artistic freedom in the Dada tradition, and as a space that celebrates a spirit of collaboration and mutual support even as the forces of capitalism drive artists toward pursuit of individual monetary success and compromise.

The history of Cuban art and Cuba is frought with deep contradictions, strange slogans, rapid reversals from freedom to oppression, unpredictable promotions, and commodification of its own story, but the Cuban artists that I met continue to produce thoughtful work which successfully brings together art and critique with intelligence and subtlety.

This entry was posted on January 3, 2012 and is filed under Espacio Aglutinador Havana Cuba.

Art in Cuba Now Part I

Art in Cuba December 2011

Gerardo Mosquera: “For the third world “primitive” is not a matter of resuscitating pre capitalist solutions which correspond to a state when internal evolution was interrupted by Eurocentric expansion of capitalism. It is a matter of making Western art in the (Third World) way and for the “(Third World) benefit. ”

( as quoted in Louis Camnitzer, New Art in Cuba, 2004.

While little that I saw in Cuba was referring to the primitive, an important fact in itself, this wonderful quote by a foremost Cuban art critic, suggests the complexity of the art in Cuba. I met with about thirty artists and was able to witness the vast differences of accessibility to international connections, money, and materials. They ranged from individual artists based in beautiful homes to artists working collectively and collaboratively and getting by on four jobs. They were all highly trained in the government supported art schools, the high school Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro and the Istituto Superior del Arte.

On the first day we met a young graphic artist at the Taller de Grafica Experimental named Alejandro Sainz Alfonso. I bought a print from him: a Greek warrior carrying a paper airplane on his shoulders. That seemed like a great introduction to the unpredictable week ahead. The Taller was founded in 1962 and 150 artists have passed through it over the years. Today it has about 20 – 30 members. The printmaking is traditional media: woodblocks, linoleum, lithography, etching.

Most of the artists I am going to write about do not have websites. Access to the internet is limited in Cuba. Think about how that changes your view of the world. Artists who have married foreigners have more access, mobility and possibilities to create websites. They seem to also have more money. One example is Reinaldo Ortega Sardiñas who is married to a Spanish wife and recently returned from two years in Spain. His work is sculpture, multimedia installation. He gave me a CD of his work (in itself an indication of resources) and told me (in English) that he does have access to the internet. His work involves some impressively expensive materials and his multimedia installations are large scale but provocative, as are his photographs.

I was struck by the photographic series, images of people entrapped by what appears to be a net made of plastic at first sight until you discover that it is made of knives or scissors. His multimedia installation was accompanied by a dance performance by the group Danz Abierta, also with funding from abroad and an enormously creative family. Danz Albierta are even on You Tube: they have performed in NYC at Jacob’s Pillow. The performance that we saw, Mal Son ( bad song – a reference to the traditional Cuban Son music), was intense: dancers abruptly walking around three short walls of a small space, with loud repetitive music– it was claustrophobic, and entrapped, like the large photographs by Sardiñas. On the back wall were filmed images of the dancers repeatedly climbing stairs. The version performed in the US was very different, as seen on these You Tube videoes: the stage was larger, so the feeling of claustrophobia was less.

For me the most provocative artists that I met were the collaborative pair Celia /Yunior, as they are known (Celia González and Yunior Aguiar). These artists work with contemporary Cuban social structures, regulations, and boundaries as they are rapidly changing. This image is from a piece filmed in a formerly elegant swimming pool, now surrounded by jagged chunks of concrete and completely unmaintained. The two artists brought some blow up rafts and floated around as if it was a luxurious place to be. Their work frequently turns on the contradictions of public and private realities.

One of their works, Bojeo, (Coasting), 2006 – 2008 involved a grant to go to Trinidad and Tobago where they played at being tourists with tourist cliché photographs, as they called Cuban hotels to inquire about their facilities. The law at that time was that Cuban residents could not stay in their own tourist hotels unless they had a foreign residence permit. So as they went around the beautiful beaches in Trinidad and Tobago, the sound track is a series of phone calls to resorts in Cuba as learned about all of the incredible eco resorts in Cuba, but in the end they were told they could not stay at any of the hotels in Cuba. The law has since changed, but the atmosphere toward Cubans in tourist hotels is still uncomfortable. For example, they are often asked for identity cards for no reason, or they are made to feel unwelcome. The piece beautifully captures both the beauty and the clichés of the Caribbean tourist life, the amazing resources that Cuba has as an ecotourism destination, and an example of the arbitrary oppression of Cuban citizens.

Another piece by Celia/Yunior called Habana 15 segundos (Havana 15 seconds) is simply recording the replacement of a Soviet era air conditioner with a Chinese one. At the moment of exchange we see through the hole in the wall to the street outside. The exchange was meant to provide more energy efficient cooling, but of course the basic reality didn’t change much.

Another piece by Celia/Yunior called Habana 15 segundos (Havana 15 seconds) is simply recording the replacement of a Soviet era air conditioner with a Chinese one. At the moment of exchange we see through the hole in the wall to the street outside. The exchange was meant to provide more energy efficient cooling, but of course the basic reality didn’t change much.

A provocative work that Celia/ Yunior created in collaboration with a group of friends is En Medio de Qué as part of an exhibition called Curators Go Home 2008. Their collaborators are Javier Castro, Luis Gárciga, Renier Quer and Grethell Rasúa. They invited friends to write on a wall about when they had been censored, either partially or completely, as well as who was the person or institution that censored them. The result was a picture of constantly changing, serendipitous censorship, dispersed information that could not be predictably mapped or even verified. The fluidity of the relationships between artists, institutions, curators, and the “system” in Cuba is its primary characteristic.

The piece became more intense when it emerged that someone from the US Interest Office had been invited to the exhibition, and the Cuban government ended by accusing the artists of being “traitors of the motherland,” a shocking experience for them. They were able to successfully defend themselves against the charge. The work exposed both the convoluted character of censorship procedures, and the ever present threat of an oppressive regime that took any exposure seriously.

This piece was created in an independent space, El Espacio Aglutinador, run by Sandra Ceballos, with various collaborators since 1994. The space is in her private home, which means that what she does cannot be censored or stopped. I will talk more about her work and space in the next installment.

“Private” home until just a month ago was not quite an accurate term, as Cubans were not allowed to sell their homes, only trade them for equivalent value. They could will them when they died. Recently though the law has changed to allow Cubans to sell their homes. Since no one has any capital to do that, one can’t help but wonder if the multinational banks are circling for new prey for their mortgages. We shall see. Up until the law was changed, though, the only piece of land that a Cuban citizen could legally own was their cemetery plot. So Celia/Yunior made a piece about that in Reserve in 2010 by digging out Celia’s back yard with an area of the same size and projecting onto it the words “Derecho Perpetuo.

The title refers to the fact that in Cuba if you own land you have a perpetual right to it, but if you don’t develop it, it reverts to the State. Of course you will always have the right to your grave! When you are dead all your rights are permanent.

This entry was posted on December 22, 2011 and is filed under Cuban Art 2011.

The #Occupy Movement: Conversations

This blog marks my exciting experiences with the early stages of the Occupy movement, before the police in the service of the oligarchy started using pepper spray and obliteration tactics. You can see I look really happy here. I was on the road lecturing on my book and I was able to visit five Occupy sites, each one has a different personality. Accidentally, I missed the mass marches, and arrived at odd times of days, spending time talking to small groups of always extremely diverse individuals. The spirit of the movement is certainly about conversation among people, among people in public, something that is unheard of in the U.S. for a long time. Although I am an ongoing activist, the amount of conversation I have had in all the Occupy sites with complete strangers from all walks of life, is thrilling. That is one of the core signficant aspects of the movement. We are all so insulated in our corners of the world with our work, our families, our busy lives. Suddenly, “#Occupy ” allows us to break out of it and share common concerns.

We are joined together, we respect each other. The people united they cannot be defeated!

The second experience for me was to feel the synergy among different causes. I have written already about Seattle and its intersections with various rallies that took place while the group was based in Westlake Park in downtown Seattle: anti war, anti police brutality, abolish Columbus Day, no genetically modified foods, and the list goes on.

In Des Moines Iowa I was there before and after a big march, the

people were friendly, and informed about all sorts of different issues, from economic justice to lesbian and gay rights. They told me on a Monday morning, that most of them were at work.

In NYC the energy center of the movement, I was overwhelmed by the thrilling intersections of so many different people, their statements, their poetry, art, politics: support for political prisoners at the General Assembly, Tibet, brutality and illegal detention in Colombia, libraries, old, young, school children doing a project for social studies, the energies are many, stoic, resistant, calm, angry, it is an “Occupy” not an occupation an elderly black gentleman reminded me when I asked for directions in downtown NYC.

SYNERGY

I am constantly amazed that people think that the Occupy movement has no demands. The demands are many and clear. I picked up the manifesto in NYC and it is a sweeping statement about all the ills perpetrated by corporations. That is the right target and the right message, all messages, anti war, detention of immigrants, black sites, environment, all come to the same problem, the corporations spending money for immoral purposes, making bombs, private prisons, surveillance.

So the conversations were real conversations.

In Northhampton, Mass, there was not one, not two, but three different actions going on in the center of this small town, an Occupy, an anti war demonstration that has been there for years, and political signs for the upcoming election ( this was November 5). The anti war protestors were at the center, the Occupy in a park not so visible, but there were anti war people included. Both included people of various ages, older, younger, children. And the Anti War people were handing out flyers about Occupy activities.

In Hartford, in the middle of a sunny Tuesday morning, I dragged my suitcase up a muddy hill when I was changing buses, and talked with the people who were awake. They had just had a big march, but they were there and I cheered them on and was happy to meet them.

As a journalist and art critic, I have photographed as many signs as possible, recording the people’s poetry pouring out on these signs. In Seattle they were short and to the point, in NYC there were really long long essays on signs!

We also know that all the Occupy Sites have libraries. I have donated my book Art and Politics Now, Cultural Activism in a Time of Crisis to three of them.

This is a video of the poet Michael O’Brian reciting his amazing poems at OWS, Occupy Wall Street. It has good footage giving a sense of the diversity of the activities going on there. I have more photographs on my artandpoliticsnow flckr photostream and videos on my artandpoliticsnow YouTube channel:Drumming at Zuccotti Park NYC with other protestors

The videos include the flags waving, the sense of so many different people standing up for what they believe in.

Even the statues!

I didn’t photograph a union ironworker whose sign said he was employed and angry. When I talked to him he said he was actually lucky becuase he had work, but he was still pissed off.

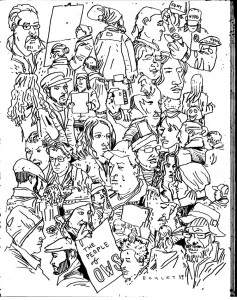

This is a general shot of the encampment. And below is the work of Joshua Boulet, an artist drawing sketches at OWS. I really like his work. Buy some of it at his website.

So poets, musicians then and now, visual artists, and everybodyas a writer, artist, poet. That is another signficance. Making signs is bringing out the creativity of every person and demonstrating the words and images are available as tools in changing the world.

As the Occupy movement is entering its new phase in mid November, it is important to hold on to the joyful connection and energy as well as the anger and discontent that is fueling this nationwide ongoing protest against the invasion of corporations into government. Here is a live stream to NYC.

One of the most succinct statements of where the country is going was made by Dorli Rainey interviewed on Democracy Now after she was pepper sprayed on November 15.

She said in response to the Mayor’s apology to her

” We spoke very briefly, and I told him that he is not in charge of what is going on, that our politicians really have lost control, and this sort of brutality is now endemic all over the United States and is being controlled by Homeland Security, by the FBI, and by the military against the war on terrorism. And it has nothing to do any longer with what individual mayors may want or not want to do.” This was reiterated in Oakland when bloggers pointed out that it was the retail oligarcy in downtown Oakland that put pressure on the Mayor there to eliminate the protestors.

The current horrifying sight of police in paramilitary gear spraying, beating up and arresting peaceful unarmed protestors is evidence of the fear that this movement has put in the elite. My image of the day is that all the police will suddenly realize that they are, indeed, also part of the 99 percent and take off all that gear and join us. The live stream today showed a police captain holding a sign ” police stop being mercenaries for the wealthy” !

I wonder if the copy of my book Art and Politics Now, Cultural Activism in a Time of Crisis that I donated to #Occupy Wall Street was trashed when the camp was destroyed or it was among the books that survived. In any case my spirit is there with the demonstrators

This entry was posted on November 19, 2011 and is filed under #Occupy movement, Uncategorized.

Sopheap Pich “Compound”

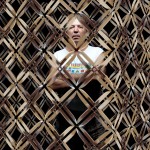

Sopheap Pich’s installation Compound at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle is an oasis of peaceful structures that can evoke anything from bombs ( according to the artist) to fish traps, chicken coops, cages, high rises or fantasy playscapes (I thought of children crawling underneath and through these light weight structures.)

There is a lot of information about the Sopheap Pich on the website of Tyler Rollins because Sopheap is having a simultaneous one person show there. It features Morning Glory made of the same rattan and wire as Compound. Morning Glories for the artist refer to a survival food in Cambodia during his childhood, when the Khmer Rouge controlled Cambodia.

He escaped with his family to a refugee camp in 1979 and then to Massachusetts in 1984. The story of the escape of many refugees with experiences in common with him is the subject of an astonishing play by Mark Jenkins, Red Earth Gold Gate Shadow Sky. The play is directed by Victor Pappas with all the actors Asian Americans, most of them Cambodian born and many who endured similar traumas as those presented in the play. There will be more performances next weekend at High Point Community Center in South Seattle.

The play is a reading and pantomine that includes Cambodian singing ( by a pop star in Cambodia) and Cambodian dancing ( by two young people), as a play within a play, performed at a refugee camp. The play begins with the American bombing of Cambodia (remember that in the winter of 1970) and it follows the disruption of one agricultural family to the city, back to the country side, taken by the Khmer Rouge in 1974, forced to produce food they could not eat for the Khmer Rouge, escape into the jungle, bare survival, escape to refugee camp in Thailand, several years of terrible treatment, sponsorship to US, placed in ghettoes here, gangs, difficulties ( Part II will treat the forced return of some of these people as a result of the new immigration laws, there is a photographic exhibition about some of them after they return to Cambodia that is devastating). The period has been presented in the 1984 film by Dith Pran, The Killing Fields and there are also books with memories of other survivors. This production is a collaboration with Don Fels, Seattle based visual artist, Sopheap Pich who has created “visual framing” for the project, and others.

Sopheap had many of these same experiences: like so many other Cambodians he went through repeated traumas. In 2003 he returned voluntarily to Cambodia. He found his current medium, the material that comes from his childhood as the son of rice farmers, the traps of fishing and of other agricultural implements.

It is a cheap material, he harvests the wood himself. His sculptures are made from the trees, split , boiled and shaped, the wood is made into a mesh with fishing wire meticulously wound at hundreds of intersections – the wire made from metal recycled from left over war materials that were carted to Vietnam and then brought back as resusable materials. This detritus of war was the foundation of construction material until recently.

But now Cambodia is having a huge and ecologically destructive development surge, particularly around the capitol. Sopheap’s studio was on a lake, a cabin on stilts. The entire lake is being destroyed for development, shown in a few photographs that accompany the sculpture.

“Compound” can be a prison or a fantasy city. It is built out of the cheapest material, it can be an allegory of the new Cambodian economy, the new cities being built as most Cambodians still live on a dollar a day. They are a compound and an imprisonment, as well as a dream and a fantasy. They invite you to enter but prevent you from doing so.

Sopheap has rearranged the bomb like shapes to be towers of this city, in previous installations they rested underneath the city. Bombs into towers, war into development, but development built on air with the work of the peasant. These simple structures suggest all of this, even as the artist has declared that they are abstract. He spoke of creating a peaceful environment in his studio, an oasis of calm with his team of workers as they build the rattan with its intersections connected by wire.

Calm and peace. Coming out of the traumas of his past. It makes a lot of sense. In his previous work ( see the website above for his other work) he created organs, body parts out of rattan, he made reference to the war traumas more directly in his statements. Now he has moved to a less specific expresssion, and he specifically stated that he was not a political artist, no doubt coached by the international art scene that being “political” is not an accepatable concept. But abstract, allegorical, metaphorical though his work is, it is deeply political as well.

Peace is a political concept.

As part of the events in Seattle, Boreth Ly, a brilliant Cambodian academic based in Santa Cruz, discussed Sopheap’s work as well as that of other contemporary Cambodian artists, You Khin, Chakra Oeur, Sarith Peou, Aragna Ker and Seckon Leang with the theme of the trauma of memory and displacement, “home” and identity. Unfortuantely the nightmares of the past are still visited on the present, not only in their dreams, but also in present day Cambodia which is being destroyed by development. Cambodian American Aragna Ker’s image of a Superman Zarathustra provides one way forward!

This entry was posted on November 12, 2011 and is filed under Sopheap Pich.

The Istanbul Modern : Hayat ve Hakikat Dream and Reality Modern and Contemporary Women Artists from Turkey

The exhibition “Dream and Reality” at the Istanbul Modern Museum provides an overview of modern and contemporary women artists from Turkey. Since women constitute many of the leading artists in Turkey, the exhibition is a valuable survey of modern and contemporary art beginning in the early twentieth century and continuing to the present.

Jointly curated by Levent Çalikoğlu Chief Curator at the Istanbul Modern, Fatmagül Berktay, Zeynep Inankur and Burcu Pelvanoğlul, the exhibition offers an opportunity to look at an important chapter of contemporary art history.

The title of the exhibition is based on the title of a novel co authored by Fatma Aliye and Ahmet Mithat. But Fatma was initially identified on the cover only as “a woman.” Fatma was also the author of an 1891 essay on Muslim Women (Nisvan-ı Islam) defending women’s rights. Although women in the late Ottoman era ( note mainly urban, upper class women)were actively promoting women’s rights, this famous first female novelist (the novel was a “Western” genre and new to Turkish writers at this point) was unnamed on the cover of the book. The position of women in the late 19th and early 20th, right before the Republic, is important to pinpoint as privileged freedom within the limitations of traditional Ottoman customs and Sharia law. ( read Reina Lewis Rethinking Orientalism for one account of some of these negotiations.)

Educational reform in the Ottoman society led to a demand for the rights of women. The first essay in the excellent catalog for this exhibition by Fatmagül Berktay outlines the relationships of women and society in the Ottoman era and early Republic. They published magazines and newspapers, and participated in meetings and charity organizations. There were by the end of the nineteenth century 40 women’s magazines and 300 books that examined the relationships of men and women. They also began to struggle for their rights. After 1908 “they began to force the limits of Sharia law and go out into the public space, to expand the means of education and to earn the right to work in the public sector, in short to bring down the walls that separated them from society.” ( p. 33) A University of Women was opened in 1914; a School of Fine Arts for Girls in the same year, although the first art school for girls had opened as early as 1864. Men and women studied together by 1921 even before the founding the Turkish Republic.

An interesting omission from the new catalog that appears in the pioneering exhibition by Tomur Atagök Cumhuriyet’ten günümüze kadın sanatçılar (Women Artists from the Republic to the Present Day) (1993) as part of the Women in Anatolia Series in honor of the 75th anniversary of the Republic, is that women’s equality in modern Turkey can be traced back much further to the nomadic cultures of Anatolia. More specifically, as Atagök summarizes women “played a central role in economic life in rural Anatolia” and produced much of the embroidery, dressmaking, carpet weaving and other handcrafts. (p.12) The tradition of sequestering women during the Ottoman years actually was an inheritance of Byzantine culture. But the “new woman” of the early Republic was still part of an oppressive, patriarchal society.

Today, as one country after another in the Middle East is throwing over dictators, the spread of Islamist ideas is rapid. Knowing how women resisted Sharia in Turkey at the turn of the twentieth century might be of use today as the new Libyan government immediately declared that it wants to institute Sharia, and Iraq has stepped back to the dark ages in its treatment of women. Afghanistan women outside Kabul are still wearing burkas as we saw in the PBS series Women, War and Peace .

“Hayal ve Hakikat” begins with benchmark historical artists, among whom the most famous is Mihri Müşfık,(1886-1950?) the first significant women oil painter in Turkey (oil painting, like the novel, was a “western” import, see Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red) . In the painting Mihri Hanim documents her assertive attitude, as well as her negotiation with the rules of the veil. Her dark veil is completely transparent. Mihri Hanım together with Müfide Kadri (1890 – 1912) led the way for women as part of the artistic culture of the late Ottoman society. There is a detailed discussion in the catalog by Burcu Pelvanoğlu of these early years. Many of Mihri’s students became prominent professional artists such as Fahrelnissa Zeid and her sister, Aliye Berger included in both the exhibition of women artists and in the main display in the Istanbul Modern. Sadly Mihri Hanim herself died in poverty far from home.

Hale Asaf, Mihri Hanim’s niece is also a major figure in the early period. More modernist, and cubist, she represents the next era of oil painting in Turkey. But the really spectacular painting in this exhibition from the mid twentieth century is by Aliye Burger, Sun Rising, 1954 that embraces expressionist colors in a stunningly near abstract composition.

Jumping to the late twentieth century, Canan Beykal honors Mihri Hanim in her piece Mihri Hanim’s Column,1993 a small doll sculpture that reinvokes the artists self portrait in three dimensions. It inhabits the gallery, imbuing the present with the past.

Tomur Atagök’s own painting and installations are an important connection from the latetwentieth century to the present. In the work in this exhibition, Plastic Paradise, or Don’t Soil,(1987) ( see beginning of blog) she works on steel panels with an expressionist style dominated by shades of pink and red. Her theme at this time was the contradictions of society for women: as the women on the right are enjoying themselves, a man with a knife threatens them. But her work also addresses environmental concerns about the planet in both the title and the suggestion of the empty landscape on the left. Atagök mixes popular culture with expressionist references to political events.

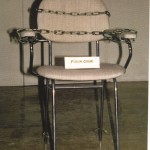

Füsun Onur also spans the late twentieth century to the present with spare conceptual art that is both playful and full of threat, as in Untitled, 1993, a chained up chair with her name on the seat. The chair is a symbol of power, property and social status ( catalog p. 130), she undercuts their function with the chain ( or in other works soft gauzy fabrics).

Nur Kocak has used a pop art aesthetic paired with photo realism to make searing comments on some of the ironies of women’s position in Turkish society. In this work she is addressing the impact of fame on Turkey’s first female director Cahide Sonku during the 1930s.

A few pioneering artists began to show conceptual art in the late 1970s. Starting in the 1980s and particularly in the 1990s, the Turkish contemporary art scene has flourished. Of the 74 artists in the exhibition, 50 of them are still active, born in every decade of the twentieth century from the 1930s to the 1980s. Ahu Antman’s essay in the exhibition catalog analyzes the relationships between these artists and larger trends, particularly feminism, in twentieth and twenty-first century art. She touches on the emphasis on empowering women in the Republic, but primarily she examines the ways in which these artists explore a wide range of contemporary approaches to media, subject matter and content, much of it explicitly relating to women in society.

Among the artists shown, the selection of the particular art work does not always stand as an indicator of the artist’s primary contribution to contemporary Turkish art. Gülsün Karamustafa’s Postposition, (1995) five quilts found in a bazaar and framed with gold gilt fabric, are an indicator of the contradictions of kitsch taste and the conservative ideology of those who buy it, only indirectly suggests that artist’s position as a major contemporary artist. Her work encompasses many themes, migration, orientalism, prostitution, women in popular culture, and much more.

The work of Hale Tenger is a crucial early installation by the artist in which she evokes potential violence in society with a great vat of red colored liquid and dozens of swords suspended above. It is not a feminist work, but it addresses the threat of violence which includes women. “The School of Sikimden Aşşa Kasımpaşa (I don’t give a fuck anymore)” 1990, was prompted by a letter bomb that killed a female professor and other acts of violence. Tenger addresses social issues, but cannot be considered a feminist artist; she does not focus on women specifically.

Among benchmark artists is Inci Eviner who has always gone her own way in terms of materials and content. Her current medium is video, but eccentrically. Fluxes of Girls in Europe. ((2010) superimposes videos of almost 70 moving female bodies on a satellite image of Europe. The women are small scale, although large on the map of Europe. They are accompanied by a text with words that describe their actions, “tear,” “stab” (catalog p.159). These women seem to be trying to break free, but failing to do so.

Many of these artists have been prominent for decades. They adopt a wide range of media and subjects, suggesting the real depth of art by women in Turkey. For example, aside from those mentioned, there are several generations of conceptual art (Ayşe Erkman, Canan Beykal, Azade Köker, Gul Ilgaz, Nancy Atakan) , social activism (Nil Yalter, Esra Ersen, Selda Asal, Ipek Duben), references to folk art or history (Selma Gürbüz, Handan Börüteçene), classical art (Candeğer Furtun,) environmental issues ( Neriman Polat, Elif Çelebi, Canan Tolon), and a combination of several of these ( Aydan Murtezaoğlu).

I will focus on a few artists with whom I was not as familiar. Şükran Moral’s provocative video Bordello, 1997, in which the artist herself plays a prostitute, is a wonderful challenge to traditional attitudes . It was actually performed in a brothel on which she hung the sign “Museum of Modern Art” and held a sign declaring that she was “for sale.” ( catalog 174). Nilbar Güreş’ video Undressing (2006) was a delightful send up of the veiling controversy in Turkey and elsewhere, as well as a compelling social commentary. The artist began entirely covered, and step by step took off one head covering after another, each one identified with a name of a specific person, but each one also representing a different social or cultural identity in Turkey. Her work underscores the oversimplifications with which this issue is often defined. Another pair of videos by Aslı Sungu’s Just Like Mother, Just Like Father (2006) also spoke about attitudes to women and what they wear, but here in the context of parental approval, as the artist kept changing between outfits that reflected different identities.

Kezban Arca Batıbeki’s installation from her Cage Projects 2 Kitsch Room Project: “Where To?” was rich with meticulous details that accumulated into a reference to the same urban migration culture that Gülsün comments on.

Güneş Terkol sews images that address identity through dress as well . Gözde Ilkin accumulates, also mainly working with fabric, a serendipitous collection of objects from everyday life. Ilkin is part of a collective called Atılkunst which created an audio tour of the exhibition which brings us back to the beginning of the story in the early twentieth century.

The exhibition with its excellent catalog essays documents the major role that these artists play in contemporary art in Turkey. Many of them are not politically affiliated with feminism per se, but, as suggested in this brief discussion, many of them address topics that engage social issues that concern women. Of course, with any exhibition of this type, there is always a question of why this group was chosen, and other well-known artists ( like Suzy Hug-Levy and Şirin Iskit, just to name two) were omitted. On the whole though, the exhibition is a major contribution to literature on contemporary art in Turkey.

One of the biggest ironies of the exhibition though was the introduction by Emine Erdoğan, the wife of the Prime Minister and the juxtaposition of her attire- elegant, but extremely conservative, with a thorough head covering with the ultra chic and contemporary Oya Eczacıbaşı the wife of the director of the Eczacıbaşı foundation.

This entry was posted on October 26, 2011 and is filed under Turkish Women Artists.