Venice Biennale Part 5 Bengladesh

This pavilion was adjacent to the Iraqi pavilion on Via Garibaldi also in the Foundation Gervasuti. Five artists are included. Each is using a different medium and addressing an entirely different subject. These artists are the contemporary heirs to a long tradition of art in this part of India, as explained in the curatorial statement by Mohamed Mijarul Quayes Those familiar with the history of art in the last century will be familiar with the Tagore family during the late Raj. Bengali artists turned to a new synthesis of early Indian art traditions, rejecting the academic art styles brought by the British colonizers.

The five artists in the Bengali pavilion today are far removed from those years, but they also show a willingess to depart from accepted norms, to reinvent new ways of thinking about old ideas. Perhaps most dramatic is the installtion by Mahbubur Rahman’s I was told to say the words

The installation is shocking even horrifying, you may wonder why I even included it: an image of pigs covered in the skin of cattle and goat, inside cages of barbed wire. He is addressing the attitudes to domestic animals in Bengladesh, cows are domesticated, but not pigs. The installation confronts us with a horrifying vision of animals trapped in the skin of another, the contradictions of our perceptions of one animal and another based on social or religious conventions. These animals are projections of prejudice and social acts, they are symbols of ideas that do not make any rational sense, or which cannot conform with civilized perspectives.

Tayeba Begum Lipi has two works, I wed Myself, shows the artist dressing for a wedding as both the male and the female ( I show only one side here)

The other is a room size installation of oversize bras made of razor blades. Both address gender issues and the contradictions in all societies betwen constructed identity, traditional attitudes to women and the realities of women. The razor blades are threatening anyone who encounters them, an armor of protection to any woman who wears such a bra.

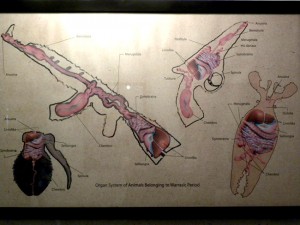

The Utoipan Museum by Imran Hossain Piplu imagined the finds of a future archeological excavation of our contemporary culture which he refers to as the Warassic Era from 1600 – 2000 AD in which all the artifacts were different type of munitions. But in his imaginary excavation the guns themselves have skeletal remains. So anyone who is reconstructing our society will recognize our main obsession with weapons, but they will also be relics of a past age. When they are discovered they will all be obsolete and unknown so the artifacts will have to be deciphered as carefully as today’s archeologists decipher the fossils of ancient geological eras. The combination of science and war with art was provocative.

These were the artists who were the most striking in the installation. In addition it included a photograph installation by Promotech Das Pulak Echoed Moments in Time, photographs of ruined sites of historical signficance in which the artist has inserted himself.

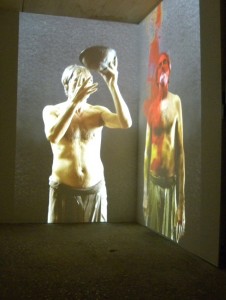

and the work of Kabir Ahmed Masum Chisty, a video, drawing installation related to the theme of Medusa

One of the pleasures of the Venice Biennale is to meet artists from all over the world. It reminds me of the fact that living in the US we are incredibly self absorbed and narrow in our daily thinking. When we think of the rest of the world it is almost inevitably in terms of war and terrorism. The Utopian Museum by Imran Hossain Piplu reminds us of that fact, while the other artists provide intersections with concerns of cultures everywhere, gender, history, and myth.

This entry was posted on June 25, 2011 and is filed under Venice Biennale Bengladesh.

Venice Biennale Part 4: The Future of a Promise Contemporary Art from the Arab World

What a wonderful name for this pavilion at this point in history. And the name was created before the Arab spring in December according to the curator Lina Lazaar. But the pavilion definitely has a sense of exhilaration in many of the works. There is no theme that ties the work together, although several of them address travel and borders. But what is obvious is that contemporary art from the Arab world can go in any direction as suggested by the signpost by Ziad Abillama with every sign pointing to “Arabes”. The artists are from many countries, and have as many trajectories. Another underlying fact is that contemporary Arab art is a hot commodity, driven by galleries and auctions, as well as collectors based particularly in Saudi Arabia, Qattar, and Dubai, and other wealthy emirates. The current exhibition is funded by a group called Edge of Arabia which is going to publish a book of the same name on the contemporary arts of Saudi Arabia.

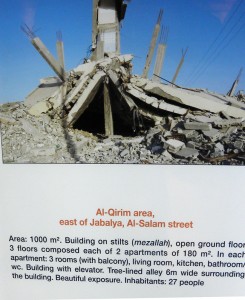

The Future of a Promise is an aesthetically compelling show, for the most part not confrontational. Two Palestinian artists make acute work about housing issues. Taysir Batniji in particular created a riveting photographic installation, GH 0809, an abbreviation of Gaza Houses 2008 – 2009 (right after the Israeli invasion of winter 2008-09). He co- opts the format of real estate advertising to present listings of houses in the Gaza strip, many of them ruined, with comments like “building on stilts… beautiful exposure, inhabitants 27 people.” His subtlety makes one aware of both the absurdity of the listing, as well as the ruinous situation in Gaza, where materials for reconstruction have been blocked (although that is finally changing following the Egyptian change in government).

Yazan Khalili’s Colour Correction adds bright colors on the buildings of the Al-Amari Refugee Camp located as he says “inside/beside/outside Ramallah City.” He speaks of the “unbearably unstable relationships between Palestinians and their surrounding landscape.” By adding day-glo pink, turquoise, purple,green, orange, on the buildings he is suggesting both the tragedy and the possibilities for a better future.

Another artist who dazzles us with an enormous work based on personal trauma and embedded in Middle Eastern culture is Lara Baladi.

As her father died of cancer, she documented the residue in coffee cups from visitors to the family in order to predict the future. Rose is a large abstract work that includes representations of six months of these residues. The large scale and specific imagery give it resonance.

Several of the artists addressed travel: Emily Jacir’s Embrace, appears to be a circular luggage conveyor that moves as you approach it, but which, in its emptiness, suggests futility; Raafat Ishak’s Responses to an immigration request from one hundred and ninety four governments.in 194 panels includes the flag of each state rendered in intentionally insipid pastels, with a summary of the repetitive responses ( or a blank if there was no response). The homogeneity of bureaucracy around the world and its ability to obstruct individual freedom is the theme. Third, and most offbeat is Manal al Dowayan’s Suspended Together. 200 fiberglass doves frozen in place in the installation. Each one is covered with the document required for Saudi women to travel (with a male relative), underscoring that no matter how powerful women become, the restrictions on their travel in the Arab world still exist everywhere. (It is intriguing that the Saudi pavilion has two women as the artists, with an emphasis on their world wide travel.)

And of course as painters, Ayman Baalbaki with his extraordinary surfaces depicting just the faces of freedom fighters wearing the characteristic keffiye and Ahmed Alsoudani’s frightening images of disaster, are entirely different in technique, but equally compelling as art.

Altogether there were 22 artists each addressing a different topic in a different medium. The real message of the show was to demonstrate the sophisticated range of art from the Arab world, carefully not called “Arab art.” Some of these artists have been expatriots for decades, others are still living in their country of origin, some are in places of conflict, others in cities of great wealth. Some are religious followers of Islam, others are Christian. All of the works are understandable to an uninformed viewer who is not Arab. Is this therefore simply contemporary art that happens to come from artists who have Arabic roots, and marketable in the international market since it does not challenge or obscure. There are many many artists who could have been included. Why were these chosen?

The curator, Lina Lazaar, poses the question “Can visual culture . . . respond to both recent events and the future promise implied in these events?” The future promise is the demands of the recent protestors in the Middle East for democracy, freedom to speak their minds, freedom to participate in their countries, to replace authoritarianism with governments responsive to the people, to have economic opportunity, even just employment. Do these works address that? Sometimes. Is the repression of those desires what lies in the future. In some cases. Is that indicated here? Occasionally.

It is intriguing to compare this to the Iraqi pavilion (and Alsoudani appears in both), in which the artists’ anguish comes through clearly as does a coherent and urgent subject, in equally successful art. The shift in the relationship of art to politics is subtle. At what point are artists willing to push us further? At the point of events such as the complete tragedies in Gaza and Iraq. At the point of the urgency of the young media artist Ahmed Basiony killed in Tahrir Square. At the point of Ai Wei Wei’s exposure of the arrests of Chinese intellectuals on social media. He has been courageously standing up for everyone else who is silent. Thank goodness he has been released. He stands as an example of what is necessary for the future promise to be realized. To stand up for what we believe in. The young workers of the Arab world have been doing just that. Let us hope that artists can be real partners in these hoped for futures as often as possible.

This entry was posted on June 23, 2011 and is filed under Contemporary Arab Art. Venice Biennale.

Venice Biennale Part 3: Egyptian Pavilion honors Ahmed Basiony Artist and Activist 1978-2011

As a direct connection to the popular surge of demand for democracy in the Arab world, the Egyptian pavilion honors young media artist/activist Ahmed Basiony ( 1978 – 2011).

He was brutally murdered in Tahrir Square on January 28th, 2011 as he was filming the uprisings. The day before he had been beaten, but had decided to return.

Basiony was a radical in his art and his politics. He was a pioneer in experimental digital media, an unusual field in Egypt because of the lack of courses and the lack of resources. He was also a tireless teacher and crucial inspiration among the younger generation of Egyptian artists

He had been filming for four days in Tahrir Square. His last postings on his facebook page are “Please O Father, O Mother, O Youth, O Student, O Citizan, O Senior and O more. You know this is our last chance for our dignity, the last chance to change the regime that has lasted the past 30 years. Go down to the streets, and revolt, bring your food, your clothes, your water, masks and tissues and a vinegar bottle, and belive me, there is but one very small step left . . . If they want war, we want peace, and I will practice proper restraint until the end, to regain my nation’s dignity.”

In the Egyptian pavilion Basiony’s footage from Tahrir Square alternated with his art work 30 Days Running in Place from a year ago. It shows the artist running in a transparent sweat suit with sensors on the soles of his shoes and his body, that translated into a visual diagram. He did this performance for one hour a day for 30 days. It expresses an incredible frustration and sense of futility. See this discussion about it. Also here is an outstanding Nafas that gives an overview of all aspects of his career.

The sense of futility and entrapment in the work, its abstract purpose, contrasts entirely with the alternating images of the crowds in Tahrir Square that he photographed in late January. On the day he was killed, his camera was taken away and has never been recoverd. His body was missing for three days. When it was finally found, it was evident that he had been intentionally shot by a sniper and his body intentionally run over. Many members of the media were killed on the same day.

So the pavilion is dedicated to this young and brilliant artist, we see the idea of his pent up frustration in his Running in Place work, and the idea of action and resistance in the footage from the square. I think his heartfelt call for action explains that he was indeed wanting the government to fall so much, for the future of his children (he leaves behind a young son and a one year old daughter) and for all the children of Egypt. Their goals were realized, the government fell. We hope that the new government will respect the wishes of the young and organized people from all aspects of Egyptian society who brought this about. It is not at all clear that they will.

This entry was posted on June 22, 2011 and is filed under Ahmed Basiony.

Venice Biennale:Part 2 US Pavilion

Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla’s multiple installations in the U.S. Pavilion featured an amusing and political conjunction of creative expression and capitalism. Outside the pavilion, a massive upside down tank from the Korean War has a treadmill installed on its right track. A USA track and field athlete runs on it priodically to make the treads turn ( and a loud noise). What is the metaphor here? Track and Field (2011) combines two of the most manic preoccupations of the U.S., war and competitive sports, both of them supersized and overcharged, run at vast expense and with nationalistic fervor. But requiring the athlete to operate the tank is also funny and subversive, suggesting the fundamental uselessness of war in its repetitive, endless, mindless, operations. The super fit USA athlete running on a treadmill on a track of an out of date tank emphasizes the futility of the operation.

Inside the pavilion are several other installations that also bring together odd pairings: Armed Freedom Lying on a Sunbed includes a scaled down replica of the statue on the top of the national Capitol in Washington D.C. lying on a tanning bed with its blinding light. The pavilion’s title Gloria, the Spanish word for “glory” evokes the feelings of the mid nineteenth century sponsors of this elaborate, Athena- like warrior goddess with its large headdress of eagle’s head, feathers, and talons. It still echoes today since the statue appears on the medals given to soldiers and civilians who serve in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Placing her in a sunbed is amusing, as though she is taking a break from her warrior goals, or it could even refer to our military might in the blinding heat of Iraq. All of Allora and Calzadilla’s works can be read in many ways, which is what makes their work so fascinating.

An ATM machine in a pipe organ, replaces the sounds made by pipes with electronic music generated by making a transaction. The creative instrument is repurposed in order to be driven by commerce, but the linear desires of buying and spending are undermined by the music that plays as a result. Finally, there are two scaled down replicas of business class airline seats on which a male and a female gymnast perform. The dancers actually perform on a balance beam that replaces the armrests of the seats. Their creative performances again render the seats unusable, undermining the status and comfort of the business class traveller. It is amusing to imagine this actually taking place in a business class cabin where driven capitalists work on their next deals as dancers extend legs and arms on adjoining seats.

Finally, three videos refer to the resistance movements to the US military exercises and environmental devastation in Vieques, Puerto Rico.

The pavilion combines humor and politics as well as simple entertainment in a way that leads us to think in different ways about capitalism, war, and creativity. IT can be deep and critical, or funny and absurd, according to our dispositions and inclinations. The element of Duchampian readymade and Cage musical humor gives the work of these two artists an opportunity to actually make strong political statements masked behind really amusing ideas.

This entry was posted on June 19, 2011 and is filed under Jennifer Allora Guillermo Calzadilla Gloria, US Pavilion Venice.

Venice Biennale 2011 Part I: The Iraqi Pavillion

I found the Iraqi pavilion at the Venice Biennale, which was located outside the Giardini and Arsenal area, to be riveting. BBC’s prestigious director Alan Yentob, a BBC filmmaker, is making a major documentary about it. Yentob is Jewish Iraqi, growing up in the UK where he came in 1948, a year in which the Iraqi Jewish community was decimated by recruitment to Israel and the founding of the state of Israel that disrupted a formerly peaceful multi cultural relationship between religions in Iraq.

His documentary on BBC, unfortunately not available online, is brilliant and thorough, interviewing each of the artists at length. I have a copy which I hope I will be able to post in some way.

Located in the decayed Gervasuti Foundation building, the Iraqi exhibition had the theme of “Wounded Water.” The theme is both absolutely pertinent to Iraq and a resonant reference point for the works in the exhibition. Each of the artists approached it entirely differently, but together they reinforce the main message, the ongoing disaster that is contemporary Iraq with a particular theme of the difficulty of finding clean water.

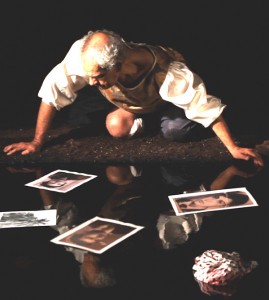

The installation in a crumbling building underscores the condition of the infrastructure in Iraq, the theme of water focuses on the most urgent problem facing everyone in the country. In Ali Assaf’s video Narcissus a man leans over a slow moving stream. The lighting is Caravaggesque, from above. Gradually detritus appears floating down the river, a box, a document, photograph, scraps, until the water is barely visible. It is a quiet slow moving piece.

The artist is from Basra a place that used to be a beautiful city. When he returned he found it in ruins, its river polluted. Assaf also has an installation work dedicated to Basra that included, when I saw it an unfinished pyramid of dates ( some contaminated with depleted uranium from the first gulf war of 1991) , family photographs from long ago, splashes of oil on the wall, and a video with a series of stills of birds caught in the Gulf Oil Spill accompanied by a childhood song about the river and birds that the artist sings in Arabic with subtitles. The intersections of oil, pollution, environmental disaster, family, nostalgia, made this one of the most compelling installations in the pavilion.

Ali Assaf, detail of al Basra with video of oil soaked birds of Gulf Oil Spill accompanied by children’s song

In Azad Nanakeli’s Destnuej (Purification) has two adjoining images, a man is pouring water over himself as at a hamam on the left and gradually being engulfed by blood and then oil on the right.

Nanakeli also made a second resonant work called Au, Water. It is an installation with three oversize traditional water spiggots, and underneath a sea of plastic bottles. Dimly lighted, the water bottles at first look like a crystalline structure, then are revealled for the rubbish they are.

By far the most amusing in a deadly way is Adel Adibin Consumption of Water, a two room installation, one sparsely furnished with a filing cabinet and a chair, and a video of the sky, the second with a video of two business men who enter into a duel to the death using long neon lights as swords.

Walid Siti’s Beauty Spot animates the waterfall that is illustrated on an Iraqi bill, a waterfall that no longer exists since Turkey built a dam north of Iraq on the Tigris river and cut off the water. He also had a stunning installation of the dried up Great Zab river, a tributary of the Tigris, made with red mylar, that filled the entrance hall at the beginning of the exhibition.

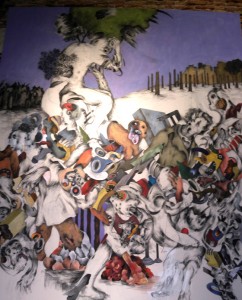

The painter Ahmed Alsoundani, appears in several other exhibitions at the Biennale. His turbulent compositions cascade on the surface of the canves, revealing horrible scenes of carnage, death and destruction. Here is an interview with him about the pavilion and his work

Alsoudani’s statement was intriguing. He went to graduate school at Yale and it was clear that he had been told that he had to be “universal” and not too personal. His statement reiterated this art school language, even as his art is wrenchingly specific once you look at it closely. Although he does make reference to other art work, such as holocaust photographs and Goya, it is also strikingly original with almost the all over surface quality of a carpet. It depicts an Iraqi holocaust without any equivocation. His art is not specific to the theme of the exhibition as were other artists, but it is certainly pertinent to the theme of disaster in Iraq.

This was a brilliant pavilion, with art grounded in extreme anguish. It addresses one aspect of the environmental disaster of Iraq. For one part of the human disaster see my previous post on the monument to murdered Iraqi academics by Dia al Azzawi.

For more commentary on the Iraqi pavilion see the very complete coverage here.

This entry was posted on June 16, 2011 and is filed under Gervasuti Foundation, Iraqi Venice Pavilion.

RABIH MROUḖ at INIVA London

Rabih Mroué─The People are Demanding

Rabih Mroué withdrew a work from his one person exhibition at INIVA in London, and left this label instead.

“The work I, the Undersigned” was supposed to be here. It is an installation which consists of two monitors and one wall text that draws attention to the intentional disregard of those responsible for the Lebanese civil wars and their refusal to give any apology to their people for all that they committed during the wars ( 1975 -1990) Beside this text one monitor shows my personal apologies for what I did during those years, and another monitor shows my face staring at you.

“I decided not to show this work today due to the radical changes, struggles, conflicts, revolutions and turmoil of a geopolitical and sociopolitical nature that are going on in my region. These changes pushed me to change the title of this exhibition from “I the undersigned” to “The People are Demanding “ From “I” to “We” as I believe that I belong to the people. But “I” seems to me not to be changing while “We” is changing very fast. Between that “I” and this “We” there is a big red question mark. ”

In the window of the exhibition is a series of verbs, extracted from the statements of protestors , lines and lines of verbs ,”to switch, to itch, to pitch, to gain, to win, to pin, to sin, to sight, to light, to smoke, to consume, to conserve, to feast, to enjoy, to demolish, to possess, to wipe, to escape, to flee, to clear, to know, to gossip, to whisper, to sneak, to seek, to yell, to turn, to overturn, to stop, to finish, to reborn, to do, to undo, to redo, to fail, to nail, to past, to last, to ice, to dice,” are the last two of eight columns of verbs.

So the verbs are the demands, but they are also acts, as we have seen in the last few months. We don’t know where these verbs will lead, but that moment of speaking and demanding is the foundation of this exhibition.

In the exhibition itself are four other works. Old House, 2003, On Three Posters, Reflections on a video-performance, 2004, and two new installations, Je Veux Voir, 2010 and Grandfather, Father and Son, 2010. Finally there is a piece inspired by Rabih Mroué’s way of working from fragments of serendipitous archives called “Possible Damage: The Inivators in collaboration with Tania El Khoury,”that constructs the student protests in London in the spring of 2011 against tuition increases, with fragments, arbitrary objects found at the time, the detritus of protest, like a fire extinguisher and a pair of googles, and blurry images of three protestors who disappeared.

So where does this exhibition fit in the work that I have written about before by Rabih Mroué, most notably his live performance at Lift Theater in 2004 “Looking for a Missing Employee” which I also discuss in my book Art and Politics Now, Midmarch Arts Press, 2011, and at Oxford in 2006 “Make Me Stop Smoking.”

Mroué is still dominant in all the works and, except in the work in the window of INIVA, We the People Demand, his presence is strong as a narrator, as a subject. He deconstructs what he is doing as he presents, always analyzing, self aware, contextualized within his own work. In the earliest work in the exhibition, Old House 2003 a video shows over and over the destruction of a building and in reverse, its return to normal. Mroué declares in a similarly looped idea: “I invent what I have forgotten on the basis that I have remembered it. After an indefinite time, I retell it to make sure I have forgotten. .. I ‘m betting on death in order to rediscover everything anew.”

On Three Posters, Reflections on a video-performance, 2004, is an analysis of a suicide bomber’s video as well as an analysis of his own actions in incorporating it into a performance piece of his own, On Three Posters in collaboration with Elias Khoury in 2000. The source video was made by a leftist martyr. He did three takes, and Mroue’s long analysis considers those three takes as identifying himself as actor, martyr and politician. Mroué wonders why he did three takes, whether he thought about how he presented himself in the three takes, what were the suicide bomber’s motivations for “getting it right”. Did it suggest hesitation, or self consciousness, or self reflexivity? Then Mroué wonders if he was exploiting him in including his video in his own performance art, would the suicide bomber wanted his video to be used in that way?

In the new installation, Grandfather, Father, Son, the artist presented the index cards of his grandfather’s card catalog for his library.They have become meaningless, without categories, just markers of an obsolete systemizing. His grandfather was a religious scholar then a Communist and the author of a book on “dialectics in Islam.” “He was assassinated when starting to work on its third volume”. Also included are manuscript pages of the never published mathematical treatise on the Fibonacci series written by his father during 1982, the year of the Israeli occupation of Lebanon and the height of the civil war. The intense abstraction of mathematical analysis in the midst of war suggests the key to why Mroué is so self aware. He understands the terror of bombs falling on his own home, and killing members of his family, but he is part of an intensely intellectual family that can see their personal disaster in a larger context, and can consciously reject or embrace pieces of that bigger picture.

Finally there is a short story that the artist wrote in 1989 that was published in a Communist newspaper. The story has eerie premonitions of what actually befell his family. The artist reads the short story in 2010 sitting directly in front of and close to the camera in his grandfather’s library.

Another new piece Je Veux Voir [ I want to See] ( 2010) also refers both directly and indirectly to his own family’s experience in the midst of war. On a large freestanding two sided billboard, he includes photographs of old posters and graffiti from Bint Jbeil, the destroyed village from which his family came, The graffiti imagery, and elusive code numbers, as well as an excerpt from a film of the same title made by Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige in which he and Catherine Deneuve walk around the destruction of the village. The gallery is filled with her repeated call for him. In the film she calls only a couple of times and he answers)

It is just a brief moment of a fairly long film during which she and Mroué as her chauffeur have various situations to deal with, stopping the car in a forbidden place, taking a wrong turn on a road that is landmined, walking on a short road near the Israeli border, with their military vehicles driving by in the distance and finally, the loud noise of Israeli airplanes on simulated attacks. Cumulatively we can experience the increasing sense of oppression, anxiety and threat. When they actually reach the village, the reality of destruction seen in the film, the reality of loss, is constructed from pieces that do not describe, but actually tell us that what is lost is gone and cannot be brought back. Mroué cannot even find where his grandmother’s house was, although he spent many summers there as a child.

Mroué is always provocative: drawing on theater, film, television, his deliberately deadpan persona dramatizes his Brechtian use of real life and real people, people that in the new works in this exhibition are himself and his family, his village, and his city.

That Brechtian awareness led him to move from I to We in this exhibition, recognizing the obsolescence of the I in the current political climate. “We the People are Demanding “responds to the new realities of the Arab world, the awakening of youth throughout so many countries, the new aspirations, the new slogans, and new desires being openly expressed. It gives this exhibition a different flavor entirely. It speaks directly from the “we” of now. The installation by the Inivators also speaks to that now.

In expanding his art to embrace the “we”, Mroué’s detachment, and even his own personal suffering are deeply altered. It is as though he has joined the world, the world of the Arab spring.

For a description of the piece omitted from the exhibition, which was shown in Utrecht from April to August 2010, see here.

Bonus Section:

I wrote about his performance in Oxford Make Me Stop Smoking in 2006, it was cut from my book, so I include it here.

Rabih Mroué’s performance in Oxford, “Make Me Stop Smoking,” addressed the artificial constructions of art production as well as history. Mroué began with titles, and the Arabic saying “a letter is understood by its title” He declared that he collected titles that were “light, but intellectual” “deep, but catchy”, an amusing analysis of a process that most artists either dismiss (with untitled) or take perhaps too seriously. Titles, for everyone but artists, are usually enormously overvalued, so Mroué’s collecting of titles that have no relationship to a work is particularly appealing as an entree into his work “Make Me Stop Smoking.” That title is either deep and catchy or irrelevant. Smoking in the context of his work is an addiction, it might be said, to collecting information of all sorts.

Mroué has collected and preserved news clippings about historical, scientific, anthroplogical or any random event, video clips of news events, television programs, rehearsal tapes of martyr videos, photographic projects ( for example photographing sewer covers), all fragments which he described as “material from the past, waiting to be used in the future.” In “Make Me Stop Smoking,” he declared he wished to rid himself of the “burden” of his non personal archives. (he also has archives of his proposals, press clippings, and documentation of his own projects).

The performance is stated to be a way to leave behind obsessions with information that has no purpose, by acknowledging that it has no meaning, no historical anchor, nor significance, because of collective amnesia. In “Make Me Stop Smoking”, Mroué himself is the main subject, instead of a person he tries to construct from an archive. He becomes the main character, his own acts are suspect and useless, as he “reinvents what he has forgotten on the basis that he happens to remember it, betting on Death to rediscover everything new.” It is a plea, in other words, to himself that he stop obsessing about past history. His conclusion, a setting of six empty frames through which he climbs in an endless and meaningless succession, suggests the entrapment he feels in his own systems of ordering.

This entry was posted on June 13, 2011 and is filed under Art in Beirut, Rabih Mroué.

Activists in Syntagma Square

I have had first hand contact with young activists in Greece. This was before the big encounters with the police. I am wondering if some of my new friends are involved with the clashes. Apparently they are already involved in a barter economy among some young people.

I also saw a huge march in the streets of Athens- and they didn’t turn out police in riot gear in Athens for these marches, as they have more recently, they just cleared a lot of streets of traffic.

Protest March in Athens: Let the Working People Become a POWER OF SUBVERSION Popular Committee Acharnes Municipality

Workers Rise Up They are Destroying the Foundation of Social Security Mass Bodies of the Athens 5th and 6th Department

The young activists camped out in Syntagma Square want to start a new democracy that comes from the people, not the oligarchs, but they are ambivalent the Communism, they don’t want to be part of any political group, they are fighting for a new future of direct democracy with freedom and dignity. They resist all isms, all political ideology. Hopefully they will work together with other political activists. Here are some links to the activists and here

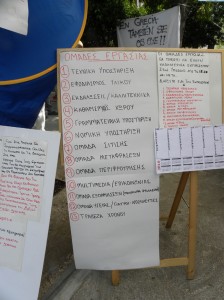

Working Groups: Technical Support, Provisioning, Events Artwork, Cleaning, Secretarial Support. Legal Support,Catering Group, Translation Group, Security Group, Multimedia Communication, Leaflet Delivery Group,Health Group Doctors, Nurses, Time Bank

The Syntagma youth also could explain to me in English what they stood for. Greece, after all, invented democracy long ago, why shouldn’t they re-invent it. They declared a people’s democracy coming from the voices of people in the square collectively, rather than from the top down.

They are demonstrating non stop against the government, ten to twenty thousand people come to the square at night. They are clearly inspired by events in Egypt and elsewhere in the Arab world, but of course the situation in each country is entirely different. There were some paintings of George Papandreou, the Prime Minister of Greece and other IMF leaders being kicked out or ridiculed.

Here is an article from an English newspaper, and another that talks about actions this week. It is a battle of people’s rights against the oppressive and greedy economic forces of the wealthy. The same battle that is being fought all over the place. In Egypt it was fuelled by workers strikes, and it still is. In Greece also there have been many strikes, as well as Italy. In Venice Italy they were getting ready for an election and the people are opposing the privatization of water and nuclear power.

This entry was posted on June 6, 2011 and is filed under economic imperialism vs democracy.

Dia al Azzawi’s monument to academics assasinated in Iraq

As of last August 2010 304 University academics have been killed in Iraq, most of them professionally assassinated. Many of them had spoken out against the occupation. That number only includes academics, it does not include the staff that belongs to other fields and institutions, who have been targeting since the beginning of the occupation, such as directors of primary and secondary schools, high schools or health workers. It does not include hundreds of scientists. It is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the destruction of the middle class in Iraq, the deaths of 1.4 million civilians, as of October 2010, the destruction of schools, the increase of illiteracy, the absence of rebuilding, the corruption of the government. There has been a systematic liquidation of technical staff and mass forced displacement of the middle class.

Dia al Azzawi has created a moving sculpture dedicated to the academics with the title Wounded Soul, A Journey of Destruction. Its point of departure is a standing horse pierced by arrows which I put on my blog last year. It is inspired by the Trojan Horse. The idea of deception and duplicity, famous all over the world: a pretended gift that brought death and destruction. Now he has also created a fallen horse Fountain of Pain of bronze that refers to the Neo Assyrian fallen lioness of Ninevah. It is surrounded by white roses made of polyester resin., each rose honoring an academic killed in Iraq. None of the murders have been solved or even investigated. According to some reports, the assassination campaign is being conducted by Mossad hit squads in collaboration with the U.S. government because scientists refused to cooperate with the U.S. on the question of nuclear development. But these murders include people in all fields of academia and ends with a famous calligrapher. The destruction of the heart of Iraqi cultural and intellectual life is destroying the future not only for that country, but for the whole world. Any academic killed represents research destroyed, students not taught, the heritage of knowledge no longer possible.

This entry was posted on May 27, 2011 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Free Ai Weiwei! Exhibitions and Protests

Two exhibitions of Ai Weiwei’s work opened in London May 12 and 13 amidst his continuing detention in China. He had a brief visit with his wife on May 16, perhaps in response to the international outcry about his arrest. We don’t know.

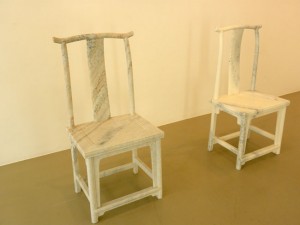

The first exhibition at the Lisson Gallery had several media. First, it consisted of large sculptures in wood and marble, most of them enlarged traditional furniture, like a chair or a moon chest or a door.

A second part of the exhibition were Han dynasty pots that had bright industrial color paints dripped over them.

The third part was a pair of videos, one showing a traditional housing area, the other a multilane freeway.

So each of these groups of works created a dialectic between historic China and contemporary life in different ways. The videos were the most straightforward, actually documenting the type of more intimate housing of traditional cities in China, and the impersonal scale and speed of modern urban China. The huge pieces of furniture were useless because they were enlarged to the point of exaggeration, except perhaps the coffin, but it was constructed at an angle that also made it useless.

The Han Dynasty pots painted with industrial paint irrevocably altered an ancient pot with contemporary paint, much as China is altering its cultural history and landscape with contemporary development.

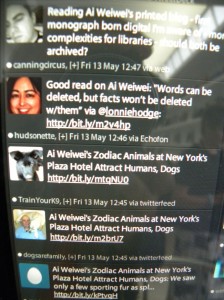

But of course it is not Ai Weiwei’s art that is the reason for his detention. It is his command of contemporary media like blogging and twittering.

His blog site was shut down in 2009, although he was twittering with 18 million people(!) right up to the time of his detention. Just before he was taken at an airport, he was tweeting about the arrest of intellectuals and dissidents in China, documenting their arrests. And of course, the Chinese government is really terrified of what has been happening in the Middle East with the people, social media and defiance of the government. The exhibition included some of the tweets as well as other media about his arrest.

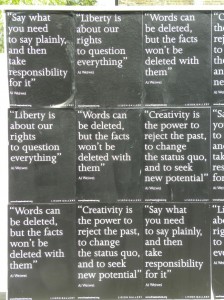

Between the two parts of the exhibition was a wall of posters with quotes from Ai Weiwei. They gave out the posters in the exhibition and it is one of these that I took to the Venice Biennale and walked around with it.

Ai Weiwei has a second show in London in the courtyard of Somerset House, which also contains the Courtauld Gallery: a spectacular group of twelve oversized bronze zodiac heads called the Circle of Animals. They are based on an historic garden in China that was designed on the principle of a European garden in the mid 18th century.

The Zodiac heads were designed by an Italian artist as spouts for a water fountain. They were destroyed by Europeans in the nineteenth centur

Ai Weiwei lived in the US 1981 – 1993 when he met Allen Ginsberg in the East Village saw the ready made works of Marcel Duchamp. Much was made of this connection in a discussion at the Somerset House about the artist. He has always been a radical in the Chinese art scene, as a part of the Sun and Stars group in the 1980s, and later. He was friends with Xu Bing in NYC as well ( more about that later). According to Alan Yentob, Creative Director of the BBC, he had an expanded notion of art and thought of himself as a readymade. But his social conscience was always present, which I don’t consider at all Duchampian. Ironic he is not, detached he is not. When he was in the US he photographed homelessness. In China he has criticized the rapid growth and destruction of the land.

For me, the most significant formative source for both Ai Weiwei’s courage and his political outspokenness is his childhood experiences. His father was part of the 100 Flowers Campaign betrayal, when Chinese intellectuals were encouraged to speak up to the government about how things could be improved and then were all sent off into rural detention. His father, a famous poet in China, and his family, were sent to live in the Gobi desert in primitive conditions. Apparently his father was forced to clean toilets.

It seems to me that Ai Weiwei could not stand by and have an easy life making money from his art. He must live his family’s tradition of speaking up to power and paying the price. While other Chinese artists are doing very well and keeping their mouths shut, he is speaking up for what is wrong. Is that Duchampian?? Hardly, but if his life and his social media and his art are all of a piece, there is a continuum that suggests erasing the barrier of art and life. And certainly his marble surveillance camera might be considered an homage to Duchamp’s use of everyday objects. But here there is no use of a real surveillance camera, only a marble one, there is no irony, no humor, only a heavy presence.

The interesting coincidence in London in mid May was that Xu Bing was also having an opening, at the British Museum, and a panel discussion. Xu Bing also spoke of honoring the past, his art work recreated a classical Chinese ink landscape using found materials in London, hemp, grass, some newspaper.

He created a shadow box and the found materials with a light shown through from the back created the simulation of an ink landscape.

But Xu Bing is now vice president of the China Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, he did not answer a question that made reference to Ai Wei Wei. He avoided all reference to politics, although he did say that the Cultural Revolution was disastrous, another period when China was destroying its cultural heritage. He also suggested that his art was a way of regenerating traditional Chinese culture.

There has been a lot more press about Ai Weiwei’s arrest in Europe than in the U.S. And at the opening press conference of the Venice Biennale, Paolo Barrata, President of the Biennale, not known for engaging political issues ( he ignored a strike by workers at the Biennale in 2009), said. “To the Chinese – it would be wonderful to have happy news about Ai Weiwei. The exhibition goes on for six months, we are waiting.”

This entry was posted on May 24, 2011 and is filed under Ai Wei Wei London and Venice, Venice Biennale, Xu Bing London.

Torture and some salvation

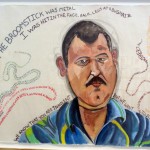

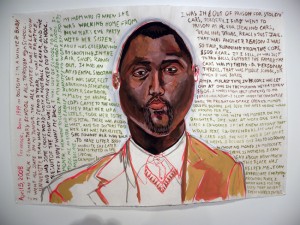

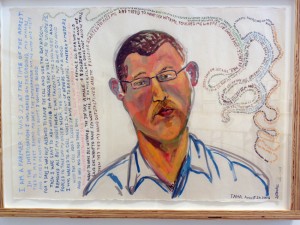

Daniel Heyman‘s two part exhibition called

“Bearing Witnes” is at Linfield College in McMinnville Oregon and the White Box of the University of Oregon gives us unimaginable suffering and inhumanity in the first show depicting men recently released from Abu Ghraib, and some salvation in the second part about a program in Philadelphia for men released from prison who are being helped to reconnect to their children and their lives.

We know about Abu Ghraib, in media sound bites, and a few images, but Daniel has been face to face with men and women who have been subjected to the most unimaginable treatment that one person can perpetrate on another. He listened as they told in simple facts what had happened to them at the hands of the people in the prison. They had been released because it was found that they had done nothing at all.

As Brian Winkenweder, art historian at Linfield College, stated in a conversation”The military machine does not work unless you are dehumanized” And he further pointed out that the people who were perpetrating the abuse were at the bottom of a huge chain of command.

It is wonderful that Heyman’s work affected Winkenweder as he is a specialist in the history of art criticism, a long way from torture in Iraq. It demonstrates the possibilities for political art that defies all restrictions. Winkenweder calls Heyman a teller of stories : I would counter with the idea that Heyman listens and records not stories, but brutal facts.

What we see, given that awareness of the monstrosity of the military machine, is that these innocent men were physically and emotionally violated in almost every way that is possible. It was lo tech, it was physical; it used feces, urine, cold water, wet floors, wet mattresses, dogs, chains, beating, stress positions, forced sex, raping of wives and daughter, raping of prisoners by both men and women, all of these acts are told by the recently released prisoners.

Heyman listened.

He wrote down what they said verbatim.

And he made portraits of the men. The gallery is a row of individual heads of men, they are dignified, and calm. It is hard to imagine surviving such abuse, but being able to at least say it must have provided some relief from the nightmare. The men are part of a class action suit against military contractors who were part of the abuse, you can’t sue the U.S. military.

In the second exhibition Heyman is listening to men who have also just come out of prison, in this case in the US. We learn not about their abuse in the prison, but the abusive circumstances of their lives, the rape of their very young mother, the murder of their very young father, their own efforts at bare survival; and then at the end we have an organization, the National Comprehensive Center for Fathers that has reached them and is offering some support.

Support for those who have been abused, who have lived at the bottom of our culture, with no resources, no opportunities. This is crucial. And Daniel in making these art works, these portrait galleries is giving us the faces and the circumstances of these individual men.

Each face is different, yellow, oranges, browns, blues, reds, and the color of face spills into changing colors of writing, the writing snakes around the head, waves in the space. The gouache colors are very strong.

Heyman listens, and the least we can do is listen also, challenging as it is to read these narratives.

- I am a farmer. I was 22 at the time of the arrest. In the interrogation, I was forced on the ground, my hands tied to my feet behind my back. The interrogator hit me with his fists and kicked me with his boots. I vomited blood. For nine days I was not allowed to leave the cell and use the bathroom ….

This entry was posted on April 28, 2011 and is filed under Torture to Salvation.