We missed the Cecilia Vicuña full installation. It was being taken down when we were there, but the label and a piece of it was still

visible

Since I didn’t fully experience it, I give you the label information:

“In the Andes people did not write, they wove meaning into textiles and knotted cords. Five thousand years ago they created the quipu (knot), a poem in space, a way to remember, involving the body and the cosmos at once. A tactile, spatial metaphor for the union of all. The quipu and its virtual counterpart, the ceque ( a system of sightlines connecting all communities in the Andes) were banished after the European Conquest. Quipus were burnt, but the quipu did not die. It symbolic dimension and vison of interconnectivity endures in Andean culture today.” Cecilia Vicuña

“27 meters pale ghostly, quipu sculptures hang from the ceiling at opposite ends of the Turbine Hall. Cecilia Vicuña’s Brain Forest Quipu continues her long-standing work with the ancient Andean tradition of the quipu. Woven together from different materials including found objects, unspun wool, plant fibres, rope and cardboard, the sculptures are combines with music and voice that emerge at mements as you move through the space.

This multi-media installation is an act of mourning for the destruction of the forests, the subsequent impact of climate change, and the violence against indigenous peoples. It is also an opportunity to create a space for new voices and forms of knowledge to be heard and understood, as we take responsibility for our part in the destruction.

Vicuña’s reimagining of the quipu contains a number of layers, sculptural, sonic, social and digital. She invites us into the “Dead Forest Quipu,” a pair of sculptures whose skeletal forms draw attention to the severity of the climate crisis and the delicate nature of our ecosystems. Their bone-white colour reminds us of bleached bark of trees killed by drought or intentional fire and other dried-out substances like snakeskin.

Placing the sculptures at either end of the Turbine Hall, Vicuña creates an alternative architecture binding the two ends of the space. Made from a range of organic materials and items collected from the banks of the River Thames by women from local Latin American communities, the work extends Vicuña’s practice of assembling found, imperfect and modest materials that she calls precarios (precarious).

The ‘Dead Forest Quipu’ sculptures are accompanied by a ‘Sound Quipu’ playing from within the sculpture and under the bridge. This sonic element, conceived by Colombian composer Ricardo Gallo, brings together indigenous music from several regions, compositional silences, new pieces by Gallo, Vicuña, and other artists, and field recordings from nature.

The interwoven moments of sound and silence span 8 hours of sonic breathing and symbolize the earth’s life in the face of the loss taking place across the globe.

The ‘Digital Quipu’ weaves together videos of indigenous activists and land defenders from regions around the world who are using digital platforms to amplify their calls. Shown on video monitors throughout the building and online, the Digital Quipu offers political and economic context for the material realities faced by communities in the ongoing struggle to protest and preserve their respective ancestral territories, communities and traditions.

What Vicuña describes as the ‘social weaving’ will extend through a ‘Quipu of Encounters: Rituals and Assemblies’. This series of global events, or ‘knots of action’, connect ancient Andean tradition and contemporary culture, inviting visitors to become active participants in the prevention of climate catastrophe.

Vicuña writes ‘ the Earth is a brain forest and the quipu embraces all its interconnections.’ Brought together , the elements of Brain Forest Quipu emphasize the contradiction and complexity of our time. This entanglement of our bodies – with both the material world of nature and the places that we live – is enmeshed in the hive-mind of technology that connects us with each other, while isolating us in new and often uncertain ways.

Vicuña suggests that we are at the beginning of a new time, one where we must first become aware of our collective responsibility in order to change destructiveness, injustices and harm. Through Brain Forest Quipu she invites us to create spaces for imagining and dreaming so that we can ‘bring our heart-minds together to give life to a new forest in a spirit of reparation.’”

Here are a few press photos:

We had a Cecilia Vicuña exhibition in Seattle in June 2019 that I wrote about on this blog. On that occasion I was fortunate to attend a poetry reading performance at which we created a community by winding a quipu around us.

We can hope that the survival of this ancient knowledge which colonialism tried so hard to wipe out, will also provide us with a way to the future on our troubled planet.

This entry was posted on May 12, 2023 and is filed under

Uncategorized.

“Extinction Beckons” by Mike Nelson gives us decay, nostalgia, destruction, resurrection, all layered in profoundly moving installations.

I first saw his work in Istanbul at the Büyük Valide Han, a caravanserai built in 1561.

That installation is one of several recreated at the Hayward, but my experience of seeing it in its first incarnation is worth quoting here:

Entrance to Buyuk Valide Han Istanbul

“Mike Nelson lived for several weeks in a crumbling market building in Istanbul, defying the usual segregation of Biennial art from ordinary people. He set up a dark room, took photographs of the Büyük Valide Han, made friends with the elderly craftsmen living there, hung up his negatives and photographs, and then left town.

Not far from the more famous Grand Bazaar, it required alert navigation through streets packed with people shopping to find the Han. The quiet courtyard felt like a dying historical space, but on entering the shop of a weaver the loud slam of his enormous antique loom filled the air. He took pride in his work, as did his father and grandfathers. In Nelson’s workshop, in semidarkness, hung his photographs of the weaver and other people he met, as well as of the ancient building itself. ”

[Here are my photos of the installation in Istanbul in 2003; in London it has some of the same elements, but lacks the total context of the building as a whole and the people who worked there. ]

“But Nelson’s work was not about him, nor about the photographs—it was about respect for the history and the poetry of the building and its workers—soon to be swept away by disintegration and globalization. Most art critics found Nelson’s area shut and believed they had missed seeing the art work. In fact, they had missed seeing the point of the art work, which was about the life and history of the ancient building and its aged workers. The fact that they thought they had missed something was perfect “poetic justice.” ( quoted in my book Art and Politics Now, 2010)”

“Poetic Justice” was the title of the 2003 8th Istanbul Biennial, curated by Dan Cameron, in which Nelson showed this work. He has subsequently shown it in Venice and now at the Hayward, where it is embedded in a series of disorienting installations that require us to again navigate carefully.

We had a personal guide through the exhibition. Her name was Charity

Henry entering the Deliverance and the Patience series of rooms

These strange objects, belong to various odd reference points.

a gambling den, a captain’s bar and a travel agent’s office.

“The rooms are deserted, but convey a feeling of unease as if they have only recently been vacated . . .

The title refers to a 17th century shipwreck, the survivors of which ( many of them prisoniers or indentured laboureres) attemted to create a free society in Bermuda before they were forced to build new ships The Deliverance and the Patience – to continue their journey to Virginia. ”

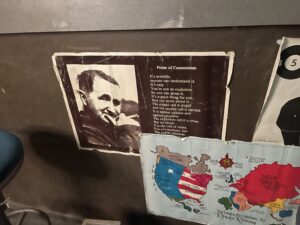

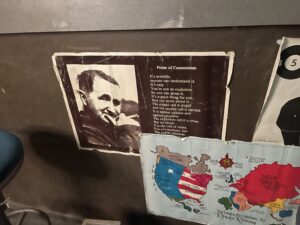

So how does the title fit with what we experience and what we see. Ideals of travel as freedom as opposed to forced travel, gambling as a hope for a better life usually lost in addiction, a Marxixt manifesto, again a hope that has not been realized.

The next part of the exhibition called “I Imposter” recreated Nelson’s photographic studio in the Buyuk Valide Han.

Another major installation “Triple Bluff Canyon”

layered references to Smithson’s early work “Partially Buried Woodshed,” with references evoking the deserts of the Middle East destroyed by war.

The exploded tires were gathered near the M25 motorway and Nelson sees them as sculptures that speak to the violence of our society.

Note the reference to Shell in the buried pipeline.

The next part of the exhibition included extensive references to obsolete tools now enshrined as sculpture.

Assett Strippers (Khorsabad)

Assett Strippers Lamassu

Assett Strippers Solstice

Assett Strippers Ziggurat grinder

The next installation Amnesiac referred in its title to a fictious biker gang. Imaginary creatures and an imaginary fire from junk

The next installation Amnesiac referred in its title to a fictious biker gang. Imaginary creatures and an imaginary fire from junk

The largest installation and most peculiar had this strange title;

‘Studio Apparatus for Kunsthalle Munster – A thematic instalment observing the Calindrical Celebration of its inception: Introduction; towards a linear understanding of notoriety, power, and their interconnectedness, furtuobjext ( misspelt); mysterious island** see introduction of Barothic Shift”

I don’t know what most of this means, but here is the installation.

The whole experience was unsettlng to say the least. Let’s go back to the title “Extinction Beckons” and that helps to put it all together. All of Nelson’s materials are gathered from junk yards, extinction, but he has brought them into a new environment, an art gallery! at the same time extinction is beckoning us, and part of the reason is a profligate disregard for what we throw away and the companies packaging all that plastic. So yes, extinction does beckon, and walking through a series of disorienting spaces can perhaps give us pause about what we are doing to our planet.

This entry was posted on May 11, 2023 and is filed under

Uncategorized.

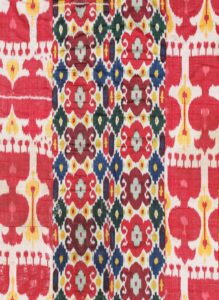

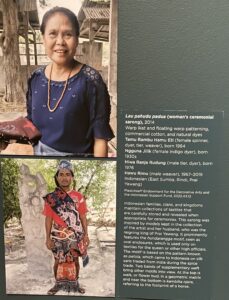

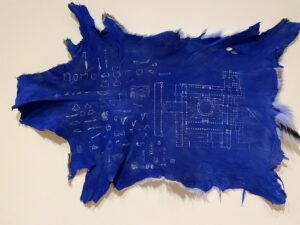

Curator Pamela McCluskey lecturing about a man’s sash or woman’s head cloth, 19th century from Myanmar

Curator Pamela McCluskey began the tour of her dazzling new “Ikat” exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum by pointing out that almost all the clothes we wear are made from oil based polyester with toxic dyes.

“Ikat” celebrates cotton, harvested and dyed by hand in a technique used for centuries. Ikat means binding, and it refers to a specific technique of binding sections of cotton to resist dying during weaving.

I was skeptical of the exhibition at first because I am not at all familiar with textiles. I thought it might be boring! I couldn’t have been more mistaken! The exhibition is riveting in so many ways, that I have been three times, and still haven’t nearly absorbed everything.

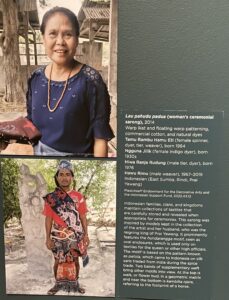

Before you enter the exhibition watch one of the videos of contemporary weavers in Indonesia and look at the work in the adjoining gallery; they provide insights into the gathering of the sources of the dyes in the jungle, the process of preparing the yarn, and the weaving, particularly featuring Tamu Rambu Hamueti queen of the Prai Yawang kingdom on the island of Sumba, Indonesia.

Ritual cloth (geringsing), 20th century Collection of David and Marita Paly Cotton, double ikat 72 × 32 in.

We also begin to learn of the ritual, mythological and symbolic meanings of the textiles, particularly the “geringsing,” a ritual cloth for coming of age girls.

But each of these textiles has a deep spiritual significance. As one weaver explained:

“The spiritual force in natural dyed cloth is amazing. Sometimes people feel as if the cloth has a soul, as if it is alive.”

—Madi Diavi, dyer and weaver in Bali, from the “Touching the Ground” documentary, 2021

The historic textiles in the exhibition are all anonymous, so this contemporary gallery provides an invaluable opportunity to more fully understand the role of Ikat in these cultures.

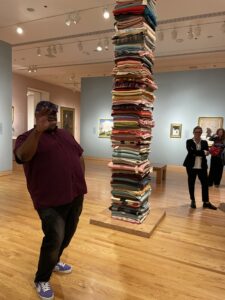

In the main entry to the exhibition we see a spectacular contemporary art work that blows up the technique itself to a huge scale. Zurash/Slipped took artists Chinami and Rowland Ricketts an entire year to complete. The process involves special organic cotton, here in over one thousand bundles bound to resist the dye. The pattern emerges only in the weaving process. Zurash/Slipped has a stepped (slipped) pattern, but the installation is like a giant loom ( 6000 verticals) of 200,00 warp yarn

strands

For the historic textiles, galleries have been entirely transformed: each region is a different color and the fabrics on the wall are now protected not by plexiglass, but by sinuous wooden platforms that prevent us from getting too close.

The regions and colors in the order we walk through them are

Japan gray blue

Africa raspberry red

India mustard

Southeast Asia Cinnamon

Uzbekisan lime green ( above)

Indonesia dark blue

Europe pale blue

Americas pink

Contemporary US white (!) and

Contemporary Ikat dark gray

Another helpful aspect of the exhibition is what the museum calls “living labels” short videos in each region that provide more insights into the process by contemporary weavers.

Indonesian looms

These historic fabrics require us to immerse ourselves in their complex patterns and meanings.

Kimono, 20th century, Japan, Paly Collection

Also crucial to remember is that they originally were an active part of life, as a kimono in Japan, or a ceremonial robe in Africa worn as a political statement in opposition to British colonialism. Here we see the textile immobilized as a flat shape on the wall. It was usually worn by someone in movement

Woman’s Sarong Hainan Island, China

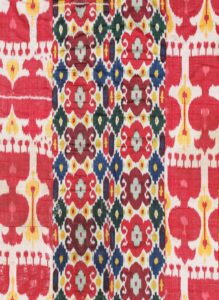

Pardah hanging, late 19th century, Silk Road (Uzbekistan), silk, warp ikat, cotton weft, 90 x 65 in., Collection of David and Marita Paly

Uzbek Pardah hanging, late 19th century Collection of David and Marita Paly Silk warp ikat, cotton weft 61 × 45 in.

In Uzbekistan Ikat weaving filled the houses as carpets on floors, walls, pillows, and room screens. Women laboriously raised the silkworms for the weavings themselves.

Uzbek Woman’s coat (Munisak), late 19th century Collection of David and Marita Paly Silk velvet warp ikat, cotton weft, silk embroidered edging 50 × 54 in.

The imagery evokes the flowers, plants, birds and insects of a paradise. The colors all come from natural sources:

red from the madder plant, yellow and green from buds of a Japanese pagoda tree, black from pomegranate peel, magenta from scale insects obtained from galls on pistachio trees, and indigo blue imported from India.

The Uzbek weaving traditions were wiped out by the Soviets, but in recent years have seen a huge revival.

Indonesian Galleries

To quote the wall label:

“Indonesia is a polestar of ikat. Like a vast net supporting Asia’s southeast region, its 17,000 islands are home to many who revere cloth as a means of honoring relationships, old and new, personal and environmental. Indonesian dyers and weavers hold on to difficult, time-consuming processes sanctioned by tradition. Some of these cloths are worn daily, and others are brought out for ceremonies and to assist in times of crisis.”

Ritual cloth (pori situtu), early 20th century

left and center Man’s shawl or hip wrapper (hinggi kawuru), early 20th century;

The Americas are also represented with their own weaving traditions and materials.

Poncho, 20th century Collection of David and Marita Paly Sheep wool warp ikat 69 × 52 in.

There are even contemporary Ikat examples: artist Polly Barton states:“When tying a knot of resist on thread, this act encodes the thread, locking in the mark of design which carries memory, an historical marker, a global or locally identifiable story which is passed down culturally in the woven membrane or fabric. My own challenge with ikat is when the threads resist, push back, push me forward as an artist while keeping me connected to the web of woven history.”

Polly Barton US Prey, from the DARE series, 2017 Silk, double ikat with additional dye, soymilk and sumi ink, 64 1/2 × 31 1/2 in.

This is just a brief taste of an extraordinary exhibition by the amazing curator Pamela McCluskey. She has travelled to Bali several times to meet artists at the “Threads of Life,” an organization that has been helping traditional weaving to survive since 1995.

“Ikat” gives us immersion in a rich tradition. Each of these textiles requires intense viewing to appreciate their process and meaning.

And the next time you buy a garment, think about who made it.

So I end with a plug for Flood my favorite environmentally friendly clothing designer based right here in the Northwest. Their hand made clothing is made from fabrics that are 100% upcycled!

This entry was posted on April 2, 2023 and is filed under

Uncategorized.

Nesting from the series Flower Serenade: A Gift of Time 2021

“Rita Robillard Time and Place”,

Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Salem Oregon

Tuesday to Saturday noon – 5pm Until March 25, 2023

Rita Robillard was a colleague of mine in the art department at Washington State University in Pullman in the 1980s. Later she moved to Portland State University and became chair of the department. We have remained close friends, partly because we have a common childhood experience growing up in downtown New York City. Here is a detail of a print she gave me of Gramercy Park where we both grew up. As you can see it is a gated park to which only people who lived on the park could gain access. As I remember it the park was hostile to children playing, so it was gated in more ways than one.

She declared at the opening that growing up in New York, where nature is scarce, led her to a love of nature and the outdoors. I feel the same way.

She moved from Manhattan to California, and then Brazil from 1971 to 1974.

The experience in Sao Paolo and in a rural village in Brazil was especially crucial. She learned new mythologies, as well as music and dance that have stayed with her all her life. She immersed herself in the luscious tropical environment as she taught art to children and also learned from them.

Above we see Heroes in the Seaweed, 1980 one of the works in the exhibition based on her experiences in Minas Gerais, Brazil near the Sumidouro River that “disappears under the earth to form a network of underground caves full of stalactites”

After returning from Brazil Robillard attended graduate school at University of California, Berkeley in the late 1970s early 1980s. Robillard responds to the “time and place” in Berkeley with a few geometric works, but soon shifts to evoking the luscious soft forms of the Sumidouro River which she describes as having “eerie beauty.”

She called this mystical and mysterious series “Spirit Ground.”

Robillard declares an affinity with the Northwest School mysticism with their emphasis on Asian Art techniques and philosophy. Ongoing study of Asian Art has been another focus throughout her career.

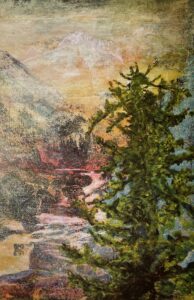

Robillard is a master printmaker.

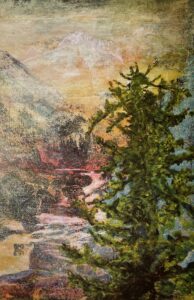

Doves in Space 2007 from the series Luminous Frontiers

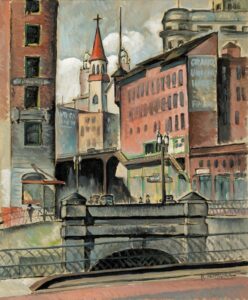

The entire exhibition consists of prints some very large in scale, from multiple plates. Technically they range from etching and screen prints, to more complex processes that create subtle textures. In looking closely at her work, we can explore layers sinking deep into another world. The work Doves in Space, 2007 ( screenprint and colored pencil on paper) from the series Luminous Frontiers suggests some of those subtle textures.

Orbs of the Forest II from the Series Waters of March 2019, screenprint and acrylic on panel

Some are views of a glowing sky imprinted with a lace pattern, and trees in the foreground. The lace pattern suggests a reference to early abstractions and patterns that connect to nature. It also includes her grandmother who created what were called anti-macassars, lace doilies that protected upholstered furniture from hair oil (maccasar). She also refers to them as a reference to a domestic environment and a type of reclamation, a type off “hopeful and protective element, a talismanic element and a shield” (Linda Tesner).

Or in contrast there are details of flowers , Queen of the Night 2021 in a recent series, “Flower Serenade: A Gift of Time” created during the pandemic.

Altogether the exhibition includes ten different series. They make a type of poem, I have mentioned several, here are all of them: Spirit Ground, Cottonwoods of the Palouse, Votives for Hanford, Essence and Artifice : Views of Spokane” Lookout/Outlook” “Time and Place”

“Luminous Frontiers” “Thicket Threshold” Polarities: Patterns in Time 1880- 2016 2.3 Degrees Fahrenheit, ” And Then Again: Rifts on the Forest and Time””Flower Serenade: A Gift of Time”

Several stand out as engaging specific places, for example the Cottonwoods of the Palouse, 1993 – 1995, painted while Robillard was on the faculty at Washington State University. There are hardly any trees in that region, but she found these beautiful cottonwoods to celebrate. ( Apparently they are no longer there)

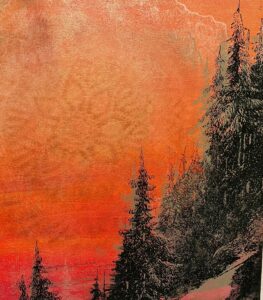

Two of the most striking and specific series are “Votives for Hanford,” and “Lookout/Outlook.”

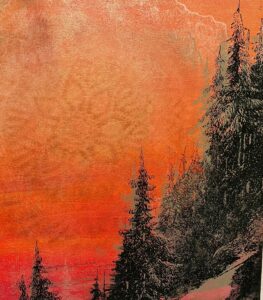

In the Hanford Series, here in Annunciation, we see a vision of holocaust in reds and blues, a flaming earth. The artist faces the intractable problem of nuclear waste with angels as witnesses to our “enchantment with invisible powers, questioning the omnipotent attitude of human beings creating a product that will have to be safeguarded for a millennium. “

Detail of textures in background

“Lookout/Outlook” 1996-2009 depicts forest fire look out towers where the artist stayed for a summer. We see a panoramic view in small digital photographs suggesting a flaming landscape against a subtle background based on filigree patterns from medieval stonewalls. Robillard points out that the lookout towers are now anachronistic, replaced by digital surveillance.

Other themes are more general but address the planetary crisis as in Conflagrations and Rain from the series Polarities: Patterns in Time 1880- 2016 2.3 Degrees Fahrenheit, 2016

The artist states: ” a mix of observation and appropriations seeking to layer sensual, tactile images that encourage the viewer to ponder the future of this planet. . . . I juxtapose flat and iridescent colors with screen printing and sand and carve each layer to create a visual history. ”

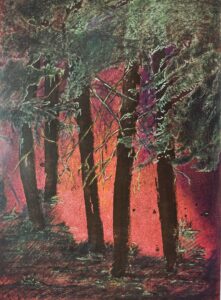

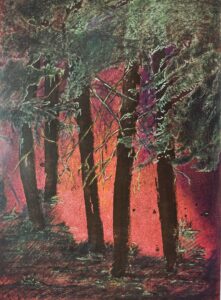

Pillars: Trees in the Hills from the series And Then Again: Rifts on the Forest and Time, 2017

Robillard sees these tall trees as “Stand -in for the people who have gone and will go before. They are pillars and graceful sentries”

Thicket/Threshold I 1989 from series Thicket Threshold

This intense work suggests nature under stress from fire and wind.

Many of her works ( not possible to show here) included reprinted historical prints from 19th century books on landscape. Here she connects to the generation of the pioneers, as the first to come into the pristine wilderness and deeply alter it.

Robillard’s work engages nature with a romantic passion. She celebrates its beauty, its complexity, and its fragility. The range of her themes, approaches, and techniques all center around different aspects of our stunning natural world. She gives us a new intimate yet majestic look at what is still surviving our onslaught. Hopefully, we will continue to be able to see these places, but if not, we have the paintings of Rita Robillard.

This entry was posted on February 9, 2023 and is filed under

Art and Ecology,

Contemporary Art,

landscape,

Printmaking,

Uncategorized.

Note: this article was published in a slightly different form in Art Access, and Leschi News.

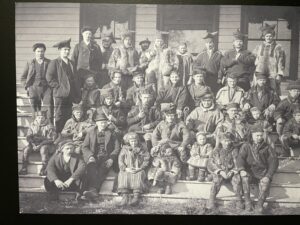

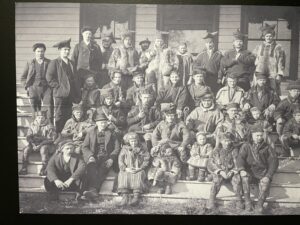

Sámi reindeer herder, Woodland Park, 1898 photographed by Anders Beer Wilse

Mygration : Tomas Colbengtson and Stina Folkebrant

National Nordic Museum until March 5

Did you know that Rudolf, the celebrity reindeer of Santa’s sleigh would have to be a female. Male reindeers shed their antlers in the winter. This is one of the many facts I have learned in order to understand “Mygration” a new exhibition at the National Nordic Museum.

In March 1898 Woodland Park visitors would have seen a surprising sight: Sámi reindeer herders and their reindeer. They came from what was then called Lapland, in Scandinavia, on a contract to teach reindeer herding to Alaskan natives! The expedition had the dramatic title of the “Lapland-Yukon Relief Expedition.”

“Mygration” addresses a strange plan to bring 100s of reindeer and Sámi herders from “Lapland” (now Sápmi ) to Alaska in order to “civilize” Native tribes there ( then called Eskimos, now Inuit and Yupik) . It was the misguided plan of Sheldon Jackson, General Agent of Education in Alaska. He spread the idea that Alaskan Natives were starving. He had first tried to bring in a much smaller number of reindeer and herders from Siberia in 1893 , across the Bering Straits, a much shorter trip!

But that effort failed.

So in 1898 he declared, as the Alaska Gold Rush was at its peak, that the Gold Miners were starving, as a ploy to raise money. The Gold Miners were devastating the environment ( the topic for a separate show, and something we never hear about) and local food gathering was in a decline, but no one was starving.

Jackson’s real agenda was actually part of the late 19th century efforts to “civilize” and assimilate Native peoples-in this case the Alaskan natives, who had not been touched by the boarding school and other policies in the lower 48 states.

Like the Alaskan natives, the Reindeer were also to be domesticated, to be used as draught animals as well as providing food.( Someone pointed out to me that Santa Claus was using reindeer as draught animals!)

It was a very long trip from Sapmi territory ( as it is now known) and Alaska!

Initially the expedition included 87 Lapps (now called Sámi), some Fins and Swedes and 530 reindeer. The Sámi were touted as “model” Indigenous people as they travelled across the sea and across the country.

By the time they reached Seattle many of the reindeer died of starvation because their diet of lichen was not available.

They stopped in the Woodland Park, perhaps for the reindeer to eat, but not surprisingly, the grass didn’t suit them.

The first small gallery of the exhibition features several photos of the Sámi by Anders Beer Wilse. In one they are disembarking from the long train ride, in another about twenty herders (it isn’t clear if that was all that survived), pose along with their families, including very young children and a few Swedes who came along.

The herders stand out in their distinctive crown-like hats and clothing made of reindeer hide.

Also in this gallery is Sheldon Jackson’s, Report on Introduction of Domestic Reindeer into Alaska, and Wilhelm Basi’s ( a cook on the expedition) Diary, 1897 – 1946

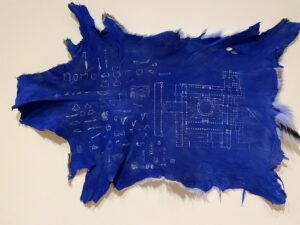

In this first gallery, don’t miss the small ceramic works by Tomas Colbengston, a Sámi artist works include two examples of photo transfer with historic Sámi images (the artist collects them). He is South Sámi and grew up in a tiny village in central Sweden. The third ceramic work depicts the reindeer, and a rendering of a figure perhaps based on a ritual drum (one of which you can also see elsewhere at the Nordic Museum).

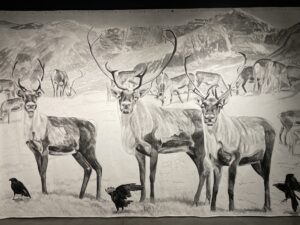

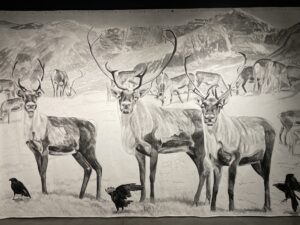

In the second gallery life size paintings of reindeer by Stina Folkebrant surround us.

The artist is inspired by Chinese ink brush paintings: all of the paintings are in shades of gray. Her focus is the relationships of animals and humans and here indeed we feel that we are wandering in a field of reindeer.

Each large painting presents a one of the eight seasons of the Sámi mountain year. We feel the powerful presence of the reindeer as we gaze back at them in the gallery. We can sense the artist’s deep feeling for her subject.

But climate change is affecting these cycles and the reindeer. As the artist told me on email:

“time is circular that is the seasons, something that returns over and over again. We also think about time as the past , present and the future. The past meets the present in our exhibition.

Climate change affects the reindeer herding because the winters are warmer and the snow melts and then it gets really cold and the ice prevents the reindeers from eating so they starve and die. The seasons are changing and that’s a problem also when the reindeers are giving birth to calves in springtime. If its to cold they die and if there is no food… etc. So climate change affects reindeer herding a lot when the seasons change.”

As described by Alaska writer Vivian Scott “Both male and female reindeer grow antlers. In early December, after mating season, male reindeer shed their antlers (unless they’re castrated males, then their antler growth has a similar cycle to female deer). Pregnant females retain their antlers throughout winter until spring.”- (Capitol City Weekly). Thus Rudolf was a female!

Her article includes many other fascinating facts about reindeer such as “Reindeer antlers are the fastest growing ‘bones’ in the world, growing up to ¾ inch per day. Reindeer have the largest and heaviest antlers of all deer species.”

Hanging in the center of the gallery are transparent plexiglass panels as well as a panel with a mirror in the center all suspended from the ceiling. Sámi photographs have been printed onto the plexiglass by Colbengston. Herders seem to move among the life size reindeer in the paintings. We are also reflected in the mirror in the center and become part of the movement.

The artists also state in the exhibition that they are evoking the Sámi concept of herd mentality

Reindeer are herd animals and being together offers protection from danger. The whole herd becomes a single organism with a thousand eyes that can detect danger; if one turns around, the others follow. People are also herd animals; they want a sense of belonging.

The story of the Sámi and the reindeer in Alaska follows many twists and turns, with various odd power plays, including being taken over by a Gold Rush family, but in 1937 the Alaska indigenous people were given ownership of the herds from the Sámi ( we are good at taking things away from people) . Alaska natives mostly didn’t like herding which required them to be away from home for months at a time, although one woman was famous for her success. They let them go to join their caribou cousins.

In other words instead of assimilation to white man’s ways, they assimilated the reindeer to their own habitat.

Some Sámi stayed in Alaska and intermarried with the Indigenous people. They are still very much part of Alaska today as evidenced in a recent exhibition in Juneau.

“Mygration” is a celebration, not a documentation of the next parts of the story. As the moving plexiglass images of the Saami intersect with the reindeer the installation perfectly conveys the magic of nomadic herders of reindeer.

National Nordic Museum

Until March 5, 2023

This entry was posted on December 27, 2022 and is filed under

climate change,

Uncategorized.

The New Installation of the American Art Galleries at the Seattle Art Museum*

Outside the first gallery is this work by Nicholas Galanin, Architecture of return, escape (The British Museum), 2022, an appropriate commentary on removing stolen Native artifacts from the British Museum. Nicholas Galanin is one of the three consulting artists for the project, he will be installing another work in the Spring.

Community and Conversation highlight Capitalism and Colonialism in the American West in the newly created American Art installation at the Seattle Art Museum. In addition to the three lead artists, the museum worked with a team of community curators and artists. This was not an advisory committee that just met once, they met many times to think about how to reinstall the collection. Seattle is fortunate to have curators and artists from a wide spectrum of perspectives:

Rebecca Cesspooch, Northern Ute/Assiniboine/Nakota visual artist and educator

Juan P. Córdova, elementary school teacher at New York City Public Schools

Fulgencio Lazo, artist and co-founder of Studio Lazo

Jared Mills, librarian at Seattle Public Library

Chieko Phillips, cultural administrator

Jake Prendez, owner and co-director of Nepantla Cultural Arts Gallery

Delbert Richardson, ethnomuseumologist

Juliet Sperling, Assistant Professor of Art History, Kollar Endowed Chair in American Art, School of Art + Art History + Design, University of Washington

Asia Tail, Cherokee artist, curator, and co-founder of yəhaw̓ Indigenous Creatives Collective

Mayumi Tsutakawa, writer with focus on Asian American history

Ken Workman, Duwamish Tribal Member and descendant of Chief Seattle

Theresa Papanikolas, Curator of American Art, seen above, and Barbara Brotherton, Curator of Native American Art began to “interrogate and re-contextualize the collection” with the help of 11 community advisors and three artists in the summer of 2021. Certainly, the death of George Floyd, and the protests that followed sparked elite predominantly white institutions across the country to rethink their own unacknowledged racism.

309 and 310 galleries before the 2022 American Art reinstallation.

Consequently, the American art galleries formerly dark and dreary and filled with art by predominantly white artists, have been entirely transformed.

Barbara Brotherton, retiring curator of Native American Art declared that the museum is following a “dramatically different approach, bringing the historical American art collection into conversation with Native, Asian American, African American, Latinx, and contemporary art. This new interpretive framework brings forward historically excluded narratives and artistic forms. Instead of seeing these communities as parallel to the so-called mainstream history, the museum now is looking at intersections. “

No longer organized chronologically, “The Stories We Carry,” features five themes some with two parts: Storied Places,

Transnational/ Trade and Expanding Markets

Transnational/The Internationalism of Objects

Reimagining Regionalism

Ancestors plus Descendants/ Faces of America

Ancestors plus Descendants/Memory Keepers.

Wendy Red Star. “Áakiiwilaxpaake (People of the Earth),” 2022. Seattle Art Museum Commission Archival ink jet prints, dibond, LED lights, electrical components, wood, milk plexiglass, 84 x 62 x 12 in.

The first theme is “Storied Places”

At the entrance the delightful Wendy Red Star, one of the lead artists, confronts us with a large lightbox: Áakiiwilaxpaake (People of The Earth). Red Star humorously and seriously speaks of how excluded she felt from the American art galleries by the boring American art genres, portraiture, and landscape.

Portraits of 70 native women, youth and even babies stand in front of the Northwest icons Mt Rainier and the Space Needle. Contemporary Native people are front and center in the present and future, rather than their usual position in the past as a prelude to white America.

Shaun Peterson (Tulalip/Puyallup, Qwalsius)’s Song for the Moon (2022) presents the Puyallup creation myth in a banner like painting. The label declares: “Native philosophies offer different ways of knowing the land, including the belief that all animate and inanimate beings are alive and indivisible from the land. Nature and its many features are thought to be sacred, not scenic.”

Next to it is Sanford Robinson Gifford’s Mount Rainier, Bay of Tacoma – Puget Sound (1875) with tiny figures dwarfed by the landscape and its golden light. These paintings, as the label comments “cast the region’s original communities as characters in the myth of the American wilderness: wild, remote, and poised to be taken over. “

The next section is Transnational

2

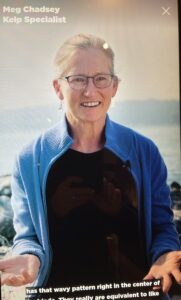

It features the sculpture of George Tsutakawa as a connection, in a work inspired by kelp called Mo (Seaweed), 1977. It is based on the seaweed that we see just beneath the surface of the sea. Near it is a short video with an interview with Meg Chadsey, kelp specialist and Gerard Tsutakawa the artist’s son who assisted in the execution of many of the works and is an artist as well.

Transnational Trade and Expanding Markets native artists responding to colonizers artistic conventions. This exciting idea moves beyond the tired and condescding concept of “deriviative” to the idea of cross fertilization. In this section we see the eminent Charles Edenshaw’s argillite totem among other works. Only Haida artists can work in argillite, but Edenshaw was brilliant at adapting to Victorian conventions in his work ( not necessarily visible here). He was commissioned at a time when Native cultures were being suppressed, to create a totem for the Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Below is a bottle covered with traditional cedar basketry techniques and a model canoe. Canoes of course are embedded in Native Culture, but this model would have been for sale.

The Internationalism of Objects white artists working with materials like Ivory from Sierra Leone, or silver from Peru both colonial extractive practices

Reimagining Regionalism

Inye Wokoma, the third consulting artist, worked as a curator here. He excavated works of art buried in storage to curate an entire gallery that “Reimagines Regionalism.” Then he wrote long interpretations with his insightful perspectives.

He is standing next to Marie Watt’s Blanket Stories: Three Sisters, Four Pelts,Sky Woman, Cousin Rose, and All My

Relations, 2007. Each blanket has a story.

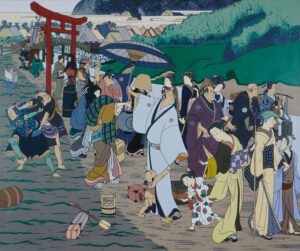

Leading off is Roger Shimomura 1978, Minidoka Series #2: Exodus, 1978 from his first Minidoka series, in the Ukiyo-e style.

Next to him, the mid-century modernists Kenjiro Nomura and Kamekichi Takata are finally given the prominent place they deserve.

My favorite juxtaposition in Wokoma’s gallery was the overlap of an elevator door of the Chicago Stock Exchange in front of a painting of Puget Sound by Albert Bierstadt. Apparently, Bierstadt never saw the Puget Sound, the painting is entirely fabricated.

Then Wokoma pulls no punches!

“The Indigenous figures along the dramatic shoreline seem inconsequential to the grand possibilities of the land: the subtext for this painting commissioned by a wealthy merchant. . . The elevator screen from the Chicago Stock Exchange (ca. 1893-94) by the “father of skyscrapers” Louis Sullivan is an utterly literal symbol of economic expansion, the overwhelming might of colonialism. Now installed so that visitors can move entirely around it and look through it, the screen offers an opportunity to consider what this gateway was leading to—and what it kept out.”

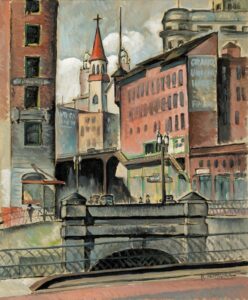

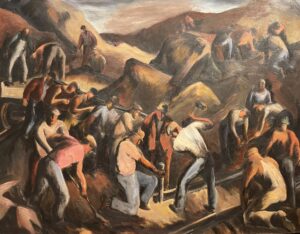

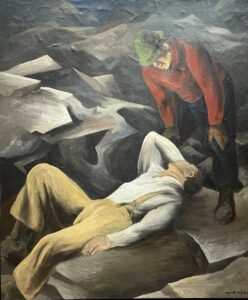

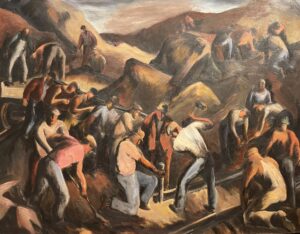

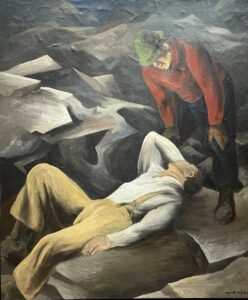

Regionalism Gallery Rudolph Franz

Zallinger

Northwest Salmon Fishermen, 1941

Kenneth Callahan building a logging railroad

Kenneth Callahan The Accident restoration project

Inye’s selection included several images of w orkers by Kenneth Callahan and other artists of the thirties, rather than the usual glorification of the Western myth of progress.

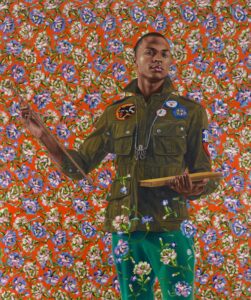

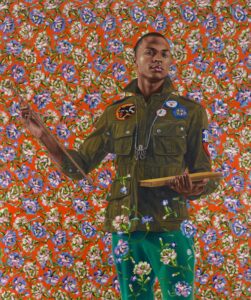

Ancestors + Descendants

Faces of America

is equally radical, for example it juxtaposes paintings by such as the well known work of Thomas Eakins and John Singleton Copley with paintings by Kehinde Wiley and a talking tintype by Will Wilson of a Lummi violin player

.

Will Wilson portrait of Nicholas Galanin

Portrait of Gwen Knight by Augusta Savage

In the last gallery “Ancestors + Descendants/Memory-Keepers” includes the only Latinx artists Alfredo Arreguin, (above) acquired only this year, and Cecilia Alvarez,(below) a gift to the museum in 1992 and never before exhibited.

Danielle Morsette Colors of the Salish Sea: Coast Salish Hybrid Tunic Dress,

The grand finale is the extraordinary basket by Suquamish artist Ed Carriere. He recreates weaving techniques from thousands of years ago by working with archeologists to recover fragments from waterlogged sites. As Brotherton states “Carriere’s precise work challenges notions of artistic hierarchy and provides a nuanced view into the brilliance of transforming humble materials into works of memory and power.”

“The Stories We Carry,” entirely rejects traditional myths of the American West such as Manifest Destiny. Instead the stories told here by a diverse cross section of voices, explore questions of conquest and colonialism, as well as exchange and tradition.

* This model for the Seattle Art Museum is far more radical than that discussed by two NY curators in this NYTimes article

In Seattle, the curators collaborated with people in the community, as well as inviting artists as co-curators. Inye Wokoma is an artist, as well as founder of the institution WaNaWari, a vibrant cultural institution that hosts all media, predominantly by people of color. it was founded to keep African American presence and culture in the Central District of Seattle which was an historically black neighborhood now going rapid gentrification.

~Susan Platt, PhD

This entry was posted on December 14, 2022 and is filed under

Uncategorized.

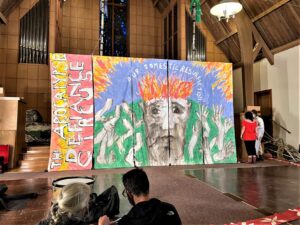

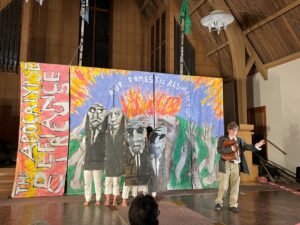

I start with a short clip of the wonderful musicians, especially the trumpet player who was music director. The musicians played parts in the skits and changed instruments ( the tuba player switched to a tiny flute for example and he was Bishop Romero) . You click on it and it downloads so you can view it.

musicians before

Here is a short clip of the opening

opening movie

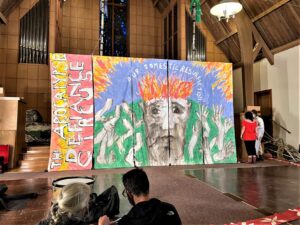

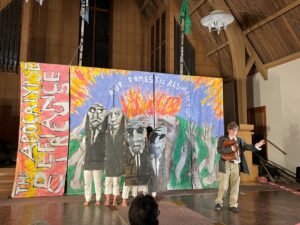

Bread and Puppet amazing performance. They were last here in 2007 with Mother Courage honoring Rachel Corrie. Now they have the Apocalypse Defiance Circus that includes COVID epidemic, Palestine, exploitation by Big Dairy, Bolsonaro’s havoc in Brazil, history of reparations, and much more with insanely huge puppets great music and staggering energy.

Here are a few images

Women on stilts riding zebras! This is the crazy fun. The women on stilts started by reading the New York Times and throwing it down in disgust, then the zebras came in and picked them up. Our connection to nature and animals, that we need them to save us, might be a message here.

The weatherman predicting disasters, and monsters and devils threatening her

Supreme Court outlaws Circuses. A clever idea, instead of hitting on the actual cases, the nightmare of so many rights being lost. But the Supreme Court is set on by lions and lion tamers and ripped apart.

.

Big Dairy trying to do away with workers by creating a self milking cow. Of course it doesn’t work and the workers come in and carry Big

Dairy away

Palestine and its tragedy.

This connected to the Rachel Corrie piece from 2007.

Assassination of Bishop Romero The placard says

“Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (Formerly the School of the Americas) continues to train death squads from Latin America

Brazil 684,000 Covid Deaths, 23,000 killed by Police, 8,069,000 sq acres of Amazon destroyed

Relentless Covid Epidemic has a fight with underpaid nurses. They win at first but then death is brought back to life and comes after them again.

History of Reparations from Haiti to the present

The finale. I have a video with music also. Click on it and you can view it.

closing movie

Elka Schumann died August 2021, the brilliant creative brains behind it as well as all the administative work and ten other things. But they are certainly still going strong.

Bread and Puppet is also in Turkey at the Istanbul Biennial!! That’s a giant Mother Earth made in Turkey with collaboration of a famous contemporary puppet artist Cengiz Özek Follow the link for a larger image

This entry was posted on October 26, 2022 and is filed under

Uncategorized.

“George Tsutakawa: The Language of Nature” at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art includes drawings, watercolors and sumi works as well as oil paintings, one of his famous fountains, several large photographs of others, and even his furniture.

The unique exhibition borrows many works from the Tsutakawa family that have never before been exhibited. The thoughtful installation emphasizes the interplay of two- and three-dimensional work.

But the dominating theme of the exhibition is the artist’s connection to nature. In a striking photograph near the beginning of the exhibition we see him sitting on the beach at low tide sketching the sea with his paper on the sand.

Tsutakawa explored both East and West aesthetics: his painting and sculpture are profoundly based in nature even when they appear abstract.

We see subtle observations in sumi sketches of shrimp, lobster, codfish, squash and leeks. birds, and trees. They are both filled with an abstract space and detailed in their realism. Tsutakawa observed the shrimp from many directions, as they gathered.

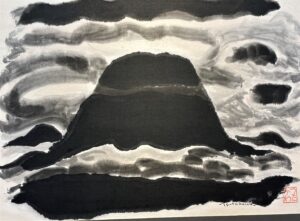

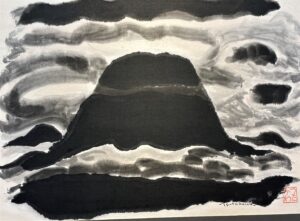

His watercolors of landscapes, particularly two of Mt. Rainier, one in transparent watercolor, the other in black, opaque sumi ink. demonstrate his close observation of changing light and atmosphere For all of us in Seattle who experience the constantly changing view of Mt Rainier, these two works resonate and represent two extremes of a spectrum from light to dark.

One of his favorite forms was the Obo, the rock that pilgrims in the Himalayas pile up to create a memorial. In his sculpture, you can see that reference, as he creates cedar or teak sculptures with both highly polished and carefully textured surfaces. These models and the painting are based on the obi shape. Once you see it you will recognize it everywhere.

Tsutakawa is best known for his bronze fountains of which there are twelve just in Seattle, and seventy-five around the country. The first and best known is “Fountain of Wisdom,” 1957–60, in front of the Seattle Public Library. These elegant metal sculptures subtly incorporate a water flow that interacts and completes their form. Here is our most familiar work, Fountain of Wisdom at the Seattle Public Library.

This entry was posted on October 21, 2022 and is filed under

Art and Ecology,

Uncategorized.

Women’s rights are front and center as Iran erupts in anger at its oppressive extremely conservative government after Mahsa Amini a young woman died from being beaten by the so-called morality police. Two 16 year old girls Sarina Esmailzadeh and Nika Shakrami, have also died in the protests.

In this country, the repeal of Roe v Wade led directly to ongoing protests all over the country. More efforts to govern our bodies.

Women’s rights have never been more on our minds.

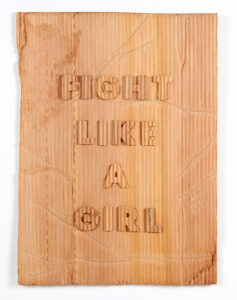

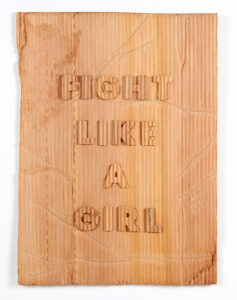

Pakistani-born artist Humaira Abid created all of the work in “Fight like a Girl,” her most recent Seattle exhibition at Greg Kucera Gallery, before the current protests. But throughout her career she has taken a stand to speak out about issues pertaining to women that are rarely discussed.

Abid points out that the term “Fight Like a Girl” has been used to denigrate girls, suggesting that they don’t fight as well as boys, but her point of view is that girls are strong, determined, and fight for everything they get.

In Iran women by the thousands are leading the nation-wide protests, and they persist in the defiance of widespread violence against them by the government.

Iran, as Resa Aslan points out in his essay “From Here to Mullahcracy” has a democratic constitution that clerics discarded: “what had begun as a vibrant experiment in Islamic democracy…” turned into a “state ruled by an inept clerical oligarchy with absolute religious power.” Iran is not a theocracy, Aslan explains, because of that constitution which “enshrined fundamental freedoms of speech, religion, education , and peaceful assembly.“

It is those discarded rights that the people of Iran, both men and women, are demanding.

Humaira Abid’s trajectory through art schools in Lahore included overcoming a lot of sexism. She studied two completely different techniques, woodworking and miniature painting. The teachers would not let her study woodworking or sculpture in art school, it was believed that only men could make sculpture, so she went to traditional wood carvers to learn.

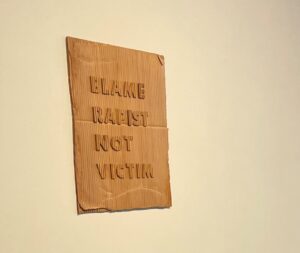

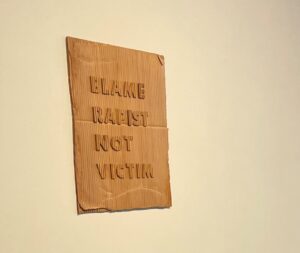

Along the first wall of Abid’s exhibition are protest posters rendered on meticulously carved pine that replicate the cardboard of protest signs. Carved on each one is a protest: “Blame Rapist not Victim,” “Enough,” “Tolerating Racism is Racism.”

Abid first seduces us with aesthetics and beauty, then gives us a punch in the face with specific imagery that speaks to the “issues people are afraid to talk about” in women’s lives both with respect to Islam and with respect to the concerns facing all women.

This exhibition includes works that address incestuous rape, miscarriages, breast feeding, and the fate of migrant women and children.

“Woman with a Breast Pump” outrageously connects the breast pump with the faucets for ablutions outside of mosques, in a tondo shape (as in a Renaissance Mother and Child): she surrounds a detailed painting of a breastfeeding mother (based on a photograph) with a halo of faucets in gilded wood.

In the series “Tempting Eyes” woman’s eyes look assertively from various Islamic head coverings on rearview mirrors (simulated in wood): the works comment on the driving ban for women in Saudi Arabia (lifted in 2017, but with other severe restrictions on women still in place). The law stands that declares that the eyes alone are dangerous and can violate the law with too much makeup. But these eyes defiantly stare right at us.

In “Woman in Black,” 2022, a small oval miniature painting of a woman covered in black holds a white rose. The stem of the white rose connects to a long chain (carved in wood) leading to a child’s head lying on the floor with a black bird sitting on it. In some ways this is the most frightening image in the exhibition: the long chain both restrains the woman and suggests an umbilical cord leading to the baby. The black bird suggest death. With the repeal of Roe v Wade the possibility of death from miscarriages has escalated.

Abid has long addressed refugees and migration, particularly the suffering of women and children, who experience rape and kidnapping. Here are images from her exhibition “Taboo” at the Bellevue Art Museum in 2017-2018

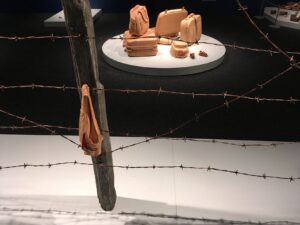

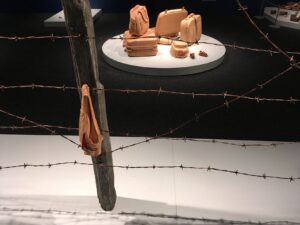

Borders and Boundaries includes a barbed wire fence entirely carved from wood. But the main point is that it makes reference to refugee camps. It is a poignant with the underpants stained red hanging on the fence. That red stain is precisely Humaira’s point about topics that are taboo, such as women menstruating while they are in the desperate straits of fleeing or in a refugee camp.

Fragments of Home Left Behind 2017 includes portraits of real refugees based on photographs

Left Laiba Age 6 Afghanistan photograph by Muhammad Muheisen Right Mona Age 5 Hassakeh, Syria photograph by Muhammad Muheisen

Sofia Hassan Mahmood and Isaac Mahmood, Ages unknown, Somalia photograph by Fazal Sheikh

The World is NOT perfect

In this pile of wooden blocks you see many different shoes each one suggesting a different identity, they refer to as the artist explained “gender, age, and culture, but also resonate on a universal level.’

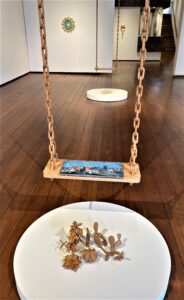

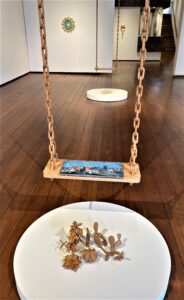

That theme appears in three swings titled “This world is beautiful and dangerous Too.” On the seat is a miniature painting of a child happily swinging in what appears to be a fantasy land. But underneath threatening looking cactus grow. Abid explained that this series began when the Taliban killed 140 children in a slaughter in 2014 in Peshawar, Pakistan.

Humaira also pursues the theme of RED in many works that are bravely confrontational ( she had an entire exhibition with that title at Art Exchange Gallery who championed her work in 2011 when she was just beginning in Seattle.

The Stains are Forever

Aspect of Motherhood

All We Need is One Fertile Egg

Art Exchange also held a show called “Istri” , a long series of works with wooden irons and miniature paintings layering comments on violence and women. In Hindi “Istri means wife and woman

and the same word means “iron” in Pakistan.

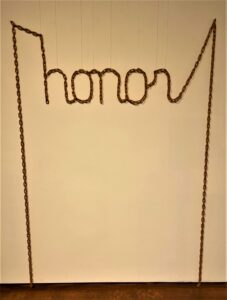

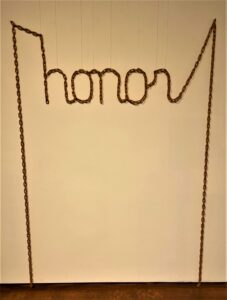

Finally “Honor’” written in carved wood chains says it all: the prison, the misuse of language, the oppression all in the name of ‘Honor.”

Abid’s beautifully crafted wood sculptures with their direct messages have never been more timely.

I wanted to add a brief note about a book I just finished reading called Women, Art and Literature in the Iranian Diaspora. While the author, Mehraneh Ebrahimi is writing about Shirin Neshat and the graphic novel Persepolis, among other books, her point also applies to Humaira’s work. She speaks of ethics, aesthetics and politics as way to humanize the Other. That is exactly what Humaira does, she is humanizing both the Other of Islamic women, as well as women in general. That is the importance of her work. The other point Ebrahami makes is the privilege of ex patriot women in their freedom to address the condition of women.

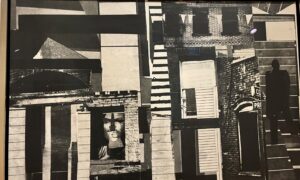

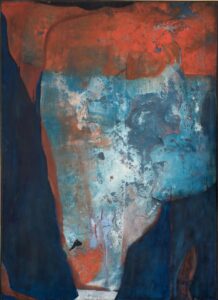

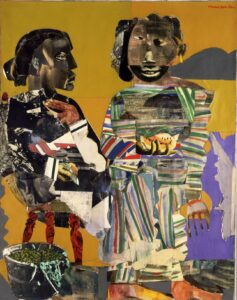

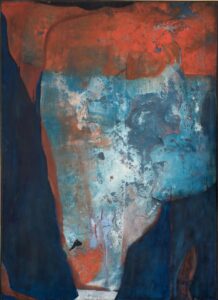

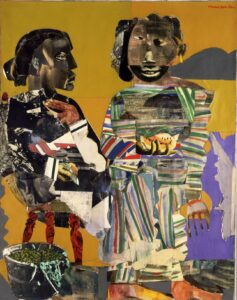

In “Romare Bearden Abstraction” the artist surprises us in every work. He constantly explores new media, color, and content. Here we see two paintings from 1959, Strange Land on the left and the Silent Valley of Sunrise on the right. Both suggest the shape of Africa, although according to the label it can be shown with either way up because the artist signed it on both ends. They are perfect examples of what I am exploring here, cloaked references.

These abstract paintings seem entirely different from his famous collage works such as Melon Season, 1967 or La Primavera 1967 , the two works here.

Or are they? Let’s look more closely. Notice the face in Melon Season is composed of many faces, you can identify at least five, suggesting many layers of identity that is a pointed variation on Picasso’s technique with split faces Her striped dress with strong parallel lines is the same pattern used in an earlier abstract painting

Untitled, Multicolored Stripes 1959

Look at the black and white patterns in La Primavera!

Look at the black and white patterns in La Primavera!

Here is a detail of Fish Fry, 1967 that clearly reveals the interplay of real objects, spoon and fork, with a complex built up pattern.

Here is a detail of Fish Fry, 1967 that clearly reveals the interplay of real objects, spoon and fork, with a complex built up pattern.

Romare Bearden began to add racially focused collaged figures to his abstract work starting in 1964 at the height of the Civil Rights, following participation in the Spiral Group. Bearden founded Spiral in his studio after the 1963 March on Washington with artists, writers and poets, in order to discuss the role of representation of the African American experience in art at a time that abstraction dominated mainstream art. As a result he turned to figurative collage.

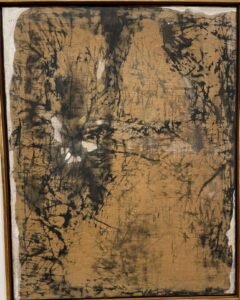

But looking at the abstractions and the figurative works in the current show we see that he was only rarely a fully abstract artist. Here are two examples that show his technical explorations.

Untitled, ca. 1956 Mixed media, newspaper and magazine clippings over watercolor and ink on paper [recto]

Looking closely I see not figures, but definitely content that connects to Bearden’s identity as an African American artist. The shades of browns, the layering from dark to light in the 1956 work is striking. As in African American’s specific and detailed description of skin color, ( look at Walter Moseley’s wonderful characters) here we have about ten shades of brown and tan. The artist himself was a very light skinned African American.

I want to explore this idea of certain colors, especially shades of brown as a metaphor of African Americans, by looking at another painting Robert Duncanson’s, Still Life with Fruit and Nuts from 1848

This painting was extensively discussed by the eminent John Wilmerding in the Wall Street Journal as “out of many parts, one painting” but what I see is the prominence of brown raisins in the center of the work, as the dominant motif; the green raisins are set aside. There are also cracked brown nuts, in other words a subtle palette that can contain many metaphors. I use this comparison to support my idea of hidden content in Bearden’s work by his use of specific shades of tan and brown.

Old Poem, ca. 1960

Oil and ink on linen

In this case, the work looks more like a spider web of lines, again on a tan surface. As we look at it though it does seem like an old page, but also a geologic formation, or an indirect reference to calligraphy released from forming characters. He studied Chinese calligraphy and sumi painting technique in the late 1950s.

His exploration of technique, experiment with pigments, global span of sources, historical studies of old masters, all appear in these abstract works. At the same time, as we look at the figurative works we can see that all of these qualities continue as the foundation for his well known works after 1965.

For example in River Mist, 1962 he works with oil on unprimed linen, casein and colored pencil cut torn on painted on board. Key to his aesthetic is his dark brown underpainting . In other words he layers and layers going from dark to light, from one medium to another. Lurking in this particular work are silhouettes that can evoke rising mists, architectural elements, facial profiles, archeological formations, or celestial events.

That fluid movement between different ways of seeing appears in most of these abstractions.

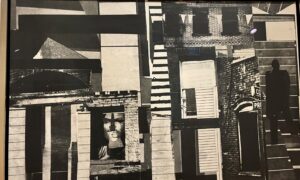

Then we have the change in 1964 in a work like 9:10, 461 Lenox Avenue of a gelatin silver print (photostat) on fiberboard or its small partner and source of the same title, made with layered collage, that suddenly gives us faces. To me it evokes Cezanne’s cardplayers, three people sitting around a table playing cards. But they are embedded in a complex abstraction of shades of brown, and white that make the faces pop out. Two men and a woman.

As Bearden worked with collage imagery in complex layers ( this is Explusion from Paradise, 1964, a very odd image, a monkey lower left, a reclining blond center, a colonial soldier and a goat right), the figure ground relationship, the scale of the figures, the utilization of abstract form, constantly shifts. As we look at these works through our exposure to his abstracted experiment work of the late 1950s and early 1960s, we see both the subjects, and the abstraction.

Sometimes an entire landscape takes over and the figure is embedded in it. In another example, the landscape is composed of figures, bound together by a subtly low key palette of yellow and greens. Looking at the subdued close valued browns, blues, mauves, yellows and reds of his abstract painting I feel they have an affinity to his African American identity, in some cases he uses at least ten shades of brown!

Even black and white suggests so many tonalities, here in Spring Way, 1964

I want to end though where he began, because the earliest works such as The Blues Has Got Me, 1944 immediately reveal his sophisticated transformations of established styles such as cubism and expressionism. This is before he went to Paris in 1950! The work incorporates music as a direct reference (he composed music after he returned from Paris). an aspect of Bearden that certainly refers again to the abstract.

Ralph Ellison said it best as quoted in the book, Memory and Metaphor, The Art of Romare Bearden, 1940-1987 ( Studio Museum, 1991) Ellison declared that Bearden conveyed the “sharp breaks, leaps in consciousness, distortions, paradoxes, reversals, telescoping of time and Surreal blending of styles, values, hopes and dreams which characterize much of Negro American history”

This entry was posted on September 21, 2022 and is filed under

Uncategorized.

Look at the black and white patterns in La Primavera!

Look at the black and white patterns in La Primavera! Here is a detail of Fish Fry, 1967 that clearly reveals the interplay of real objects, spoon and fork, with a complex built up pattern.

Here is a detail of Fish Fry, 1967 that clearly reveals the interplay of real objects, spoon and fork, with a complex built up pattern.