Happy New Year! Resist Ignorance!

I am starting the New Year with a quote from someone who declares himself to be ignorant.

“But I can’t tell Jose Cuervo from Al Queda operatives by looking at them because they cut their beards off. It’s like trying to get fly manure out of pepper without your glasses on you know? I mean not a racist thing, but they’re all brown with black hair and they don’t speak English and I don’t speak Arabic or Spanish.” “Return of the Nativist,” New Yorker, December 17, 07.

This type of ignorance is the basis for many of the major problems facing the United States from the President down to the ordinary everyday racist like this man.

In searching for art online about immigration, I found a website of excellent political cartoons. Perhaps the subject is too far away from New York City and too complicated for most post modernists steeped in how to distance themselves from on the ground facts. Let me know if you know of artists addressing the subject!

Above is one of the dozens of cartoons at http://www.newsart.com/m/m48.htm. This cartoon is by Barry Maguire.

Ignorance manifested itself also in the Walt Disney big budget film National Treasure: Book of Secrets recently released. I went to see Helen Mirren as an action hero, and I wasn’t disappointed, but the ignorance of Walt Disney studios, their willful laziness with respect to Mesoamerican culture and civilization is disturbing.

Suggesting that the hieroglyphs are pointing to a city of Gold is such a stereotype: it was the Europeans that were greedy for gold and pursued it as a form of capital, the Mesoamericans gave gold a different value, usually ornamental metalwork, a technique that was used hundreds of years after the Olmec. The City of Gold is called Olmec, when it is obviously a fantasy of Mayan and Aztec through the lens of Euro American obsession with gold.

The reference to human sacrifice (and was it different from the colonial slaughter or our own wars ?) and emphasis on gold, are simplistic distortions about a highly complex culture that predates Maya and Aztec by many hundreds of years. Mirren’s character, as a professor, is hostile to treasure hunters, making a bow to the movie’s own stereotypes. A quick read by either the set designers or the writers would have made the references more accurate and less cliched. One surviving type of Olmec artifact is colossal naturalistic heads which could easily have been used as a basis for the lost city in the movie.

But I guess feeding cliches to the American public is what Walt Disney is all about. (I say that sadly as I have to confess that my own father worked for Walt Disney in the 1950s as a consultant on Secrets of Nature. He brought me home a photograph personally autographed by Disney that I still own).

While National Treasure Book of Secrets may see itself as harmless, the perpetration of ignorance and stereotypes is never harmless. Granted, in the end, the Helen Mirren character miraculously transforms herself from a glyph specialist to the leader of a major archeological dig, and the main characters vindicate their ancestors rather than gaining personal wealth, but the over all message is find the – “precolonial” as they call it – gold.

Stereotypes and cliches perpetuate ignorance and racism. They can also lead to oppression and death as we see in the war in Iraq and on immigrants both Arab and Latino.

This entry was posted on January 2, 2008 and is filed under Immigration, National Treasure Book of Secrets.

Selma Waldman’s Black Book of Aggressors V

These are only two images from the most recent Wall of Perpetrators by Selma Waldman.

The Wall consists of a total of 40 images all drawn on black perforated paper.

The intense chalk lines are bearing witness to the atrocity of the torture.

The top drawing in red and blue chalk on black paper is Testicles V

The prisoner is sprawled helplessly over a stool with his hands shackled to his ankles.

He is being given electric shocks by two soldiers on either side of him. His body arches in pain. One soldier holds the wires directly to the prisoners testicles, the other sends the shock from a box.The red is the red of fire, of electricity, of pain, of torture

The second work is Waterboarding. It is one of six images of waterboarding in the series. Each one specifically describes the process with detailed writing. Waldman carefully researched exactly what happens during water boarding. She forced herself to penetrate to the factual heart of this darkness and to represent it. This one shows the prisoner on his back, shackled as two soldiers on either side simultaneously pour water on his face, which is covered with a cloth. The soldiers stand resolute, one is smoking a cigarette, the other looks fixedly at the stream of water and the suffering prisoner with no expression. The white is the white of drowning.

The other waterboarding images have texts

“strapped to board upside down

immersed in wet towel to fake drowning

used to impose anguish without leaving marks. “

Another has this text

“tied to board

unable to move

head lower than feet

cloth held tight over face

waterpoured over cloth

fear of death by asphyxiation

A third has this text

water poured over cellophane pressed to face

gag reflex kicks in

drowning detainnee screams in agony to stop

Another says

“waterboarding falls into the area of professional interrogation techniques” ex CIA head

The image above is the last image.

All of these acts are present. Look at these works and think about the loss of humanity for all of us as these acts are committed. They must be exposed in order to be understood and protested. Just below this is my grandson. All of these prisoners and all of these torturers came from a mother’s pain and joy and love. How did we all get from there to here. We must stop this inhumanity.

This entry was posted on December 18, 2007 and is filed under water boarding Selma Waldman.

my new website and my new grandson

www.artandpoliticsnow.com is now online and available for everyone to see!

and this is my brand new grandson for everyone to see!

Art and Politics has a lot to do with the future of our planet which belongs to this tiny infant and the other children of the world. Let’s make sure we stay on the task of making it as good as possible.

This entry was posted on December 13, 2007 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Roger Shimomura Minidoka on my Mind

“I offer this exhibition as a metaphor for the impending threat posed by current times. …” Roger Shimomura 2007

Roger Shimomura’s new work shown in his exhibition “Minidoka on my Mind” at Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle confronts us directly with both the past and the present.

This is Shimomura’s fourth series on the subject of the Japanese Internment during World War II. He based earlier series on his grandmother’s diary, and as he has described it to me recently, memories that have become fact: “memories that were galvanized from retelling and then spawned other memories, and got longer. ”

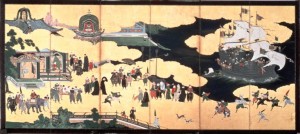

He was in the camps himself as a very small child, so he does have some memories, but that is not the point of this exhibition. He has made these works in deep conversation with Western modernism, both minimalism and Pop Art, as well as a particular period of Japanese art, Namban.

by Kano Naizen

Azuchi-Momoyama period

Pair of six-fold screens, color on gold-leaf paper

Height 155.5 cm; Width 364.5 cm (each)

(Kobe City Museum)

Namban screens as seen here are the work created in response to the arrival of Europeans in Japan during a brief period of time, in the late 17th early 18th century.

Namban means “southern barbarians” and refers to the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese by ship, bringing both commerce and religion. While the subject can find a parallel in the Iraq war invasion, as to how we perceive ourselves vs how the Iraqis perceive us, (certainly as Barbarians), as well as the overlapping of religion and commerce, the comparison also extends to the compositions and subjects of these paintings and their colors. ( This comparison was suggested by a current exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum, Japan Envisions the West, and its symposium, December 1, 2007)

This large Namban screen, ( the right half of a six panel group by Kano Naizen, the whole measures five feet high and over ten feet long) ) uses aerial perspective, a palette of gold and black, and tiny figures very much like Shimomura’s American Infamy above (which is an overwhelming 6 feet high and 10 feet long). In the Namban screen, a large ship on the right looms in the black water The ship bears religious icons and trading items that the captain is planning to trade in Japan.

The screen bears an intriguing comparison to Shimomura’s large painting. In Shimomura’s work the person who is above the scene is not implied but depicted as a large foreground figure with binoculars looking down from a watch tower on the inhabitants of the camp. The camps were in arid desert settings, so the gold ground of the Namban scene is echoed in the yellow of the desert. Between the small structures are many small specific figures, a panorama of types in both paintings. Shimomura declares irrefutably that surveillance controls lives. In the Namban painting that is not so obvious, although the Jesuits were forced to leave Japan in the early 18th century because the shoguns recognized that they were threatening traditional values in Japan.

Shimomura’s smaller paintings are no longer intended to be memories or facts. They are constructions, based on a highly sophisticated transformation of a grid setting into layers of space, insides, outsides, barbed wire and cheap housing, modernism turned back onto itself from utopia to prison. This grid ( so lauded in modernist theoretical discussions) is flat, it barely separates those who are free and those who are not.

In Classmates, the blond blue eyed girl has a dress that touches the shoulder of the Japanese American girl behind the wires. Both hold apples, both are dressed in fashionable clothes, both smile, both are the same age. The wire thin line that separates them is both literal and metaphorical. These girls could be representing today’s shattered friendships as the Immigration and Homeland Security forces sweep into neighborhoods and remove random people ( Arabs? “Immigrants?) for no declared reason, intern them in prison without charges, shatter families, friendships and lives.

The title work Minidoka on My Mind is perhaps the most astonishing. It shows a young boy painting a “minimalist” composition, but here is no red, yellow and blue primaries, or black zips on a white ground referring to the “Stations of the Cross” and inferring higher realities. Here are horizontal and vertical yellow lines and black squares. Looking closer the painting within the painting is an exact replica of the actual construction of the building the child is painting. It is a representation of the idea of prison when imagination is confined to the wall in front of you. It takes the minimalist/grid tradition and turns it on its head. The blackness becomes not an opening, but a closure, the empty spaces that we have glibly interpreted in Mondrian’s subtle compositions, are now flat, cheap walls. The child is obsessively painting a row of dots, these are the nails that hold the flimsy structure together. The grid continues to the left of the building and the child, scoring the landscape, the sky, and the world with its rough wire lines.

Shimomura and other members of his generation are offering information on the history of racism in this country with their work on this topic. It is now more current than ever.

Shimomura fears that the persistance of racism in our society is not fully grasped by the younger generation, (70 per cent of Asian Americans, for example, are in biracial relationships.)

This little boy is about much more than painting, it is about forgetting and willfully eliminating the larger context of what that internment camp meant in the context of the large social forces that shape decisions. He cannot see beyond the wall that he is painting, but we can. We are outside his space, looking down on him, like the soldier who is standing in the watch tower. Surveillance is available to us, but we do nothing to liberate this child, to understand the conditions of imprisonment, or to ensure that laws will prevent it. In the end Shimomura’s work turns back to us as the perpetrators. We are still outside the prison, but for how long will we remain there, if we ignore reality. Our position is not one of power, it is one of ignorance. The little boy understands his situation more completely than we do.

This entry was posted on December 1, 2007 and is filed under Roger Shimomura.

Iraqi Women by Nadje Sadig Al-Ali

Since I am on the subject of books. Iraqi Women is another crucial book. The subtitle is “untold stories from 1948 to the Present” . Nadje has interviewed a cross section of women who left Iraq at various times ( some only briefly), provinding one window into the history of Iraqi women since the 1940s, with a brief look backward to the early twentieth century. It discusses the incredible support for women provided in the 1970s, professional training, child care, good salaries, transportation to and from work. A model of what a society can do that trully wants to support women as full human beings. But already in the 1980s the situation changed, during the Iran Iraq war, when women were encouraged to produce babies, and in the 1990s, during sanctions, problems escalated exponentially. Since 2001, everything has gone down hill to the present almost total destruction of the country of both the past, present and future of the country as Reshad Selim, another major Iraqi artist puts it.

This painting is by Maysaloun Faraj, the artist and director of Aya Gallery London.

The title is Weeping Palms, Stolen Childhood, 2004

This entry was posted on November 21, 2007 and is filed under Iraqi Women.

Dahr Jamail’s Beyond the Green Zone Read It

Dahr Jamail’s book, Beyond the Green Zone Dispatches from an Unembedded Journalist in Occupied Iraq, is an essential book to read for anyone who wants to hear another side of the situation in Iraq. What makes it so potent is that he is not aggrandizing himself, he is not reporting the war per se, he is simply talking to as many Iraqis as he can, especially focusing on the bombing of hospitals, shooting at ambulances, using cluster bombs as well as phosporous incendiary bombs on civilians. As a sub theme he accounts his own observations of the continual degradation of life in Iraq.

Of course as a man he had access to a lot of places that a woman would not have been able to report on, and his interviews are almost entirely with men. This is the new Iraq, where formerly secular women are now covered from head to toe in black when they leave the house, unable to work, and unavailable, for men to talk to outside of their families. The new Iraq from which the Middle Class is leaving as fast as it can.

( See http://riverbendblog.blogspot.com/http whose writer is now in Syria as one record of life from a woman’s point of view) .

Most of Jamail’s contact with women and children was encountering them wounded in a hospital, or observations of their impossible day to day challenges of lack of water and electricity, lack of medical care, and basic security. In those observations he brings home in one way the day to day nightmare that families are experiencing in the war.

And Congress just keeps voting money for the corporations  (disguised as support for the troops). Bought and sold to their pieces of the pie.

(disguised as support for the troops). Bought and sold to their pieces of the pie.

A particularly potent part of Jamail’s book describes the absence of any of the promised multi million dollar reconstruction by Bechtel . Based on his own on the ground observation and interviews with people who have no water in chapter 6 Craving Health and Freedom”

Here is a quote from near the end of the book, commenting on the second assault on Fallujah.

“The second assault on Fallujah was a monument to brutality and atrocity made in the United States of America. Like the Spanish city of Guernica during the 1930s, and Grozny in the 1990s Fallujah is our monument of excess and overkill. ” 239

Another major contribution is Jamail’s documentation of the disconnect between mainstream reporting and facts on the ground. Repeatedly the US military and media reported outright lies, distortions, and invented stories, as well as suppressing other stories and the reports of unembedded journalists. For example, Jamail describes the rally by the resistance after the first attack on Fallujah, after the embedded journalists and military withdrew.

Therefore, today, as we see the New York Times report on “Baghdadi’s sigh of relief,” because of the “success of the surge” we can place it in the bigger picture of the complete disaster on the ground and the campaign of disinformation that Jamail reports on in his dispatches and his book.

http://www.dahrjamailiraq.com/

Above is art work by Hana Mal Allah Baghdad Artist. It is a book called Baghdad Map, US Map. Hana Mal Allah, see my earlier entry on her work, actually burns her work in partnership with the burning of the city of the ancient and beautiful city of Baghdad. The work is currently part of the exhibition Red Zone/Green Zone at Gemak den Haag, an exhibition focusing on “urban security policies and the withering of public space from Baghdad to Den Haag” http://www.gemak.org/tentoonstellingen.html

This entry was posted on November 20, 2007 and is filed under Iraq.

Kara Walker

Kara Walker has really started to talk loudly about miscegenation. Although I have seen her works for years, they always seemed to me to be perpetuating racism rather than countering it, but her recent retrospective as well as her new works, on display at Sikkema Jenkins and Co in Chelsea, are unavoidably challenging.

In the newest work Walker links abuse of African-Americans based on research with contemporary examples of torture and abuse in Iraq and Sudan, the message of the abuse of humans is loud and clear. White people actually

can’t avoid the past here. It is all so clear that torture is an American way of life.

The work here is part of a series based on research in the “Bureau of Refugees, Freedman and Abandoned Lands – Records, “Miscellaneous Papers,” National Archives M809 Roll 23 (anyone can access this source)

The show is called:

“Search for ideas supporting the Black Man as a work of Modern Art/Contemporary Painting; a death without end and an appreciation of the Creative Spirit of Lynch Mobs” .

The title is complicated and ironic. It is worth an essay in itself.

What Walker confronts us with are the horrors of the racist acts of which the US human male is capable based on documentary evidence. There is a direct correlation in the language and actions of today’s US human males and females in the war in Iraq and in the starving of millions in Sudan. Our roots in terrorism, both of Blacks and Native Americans, are deep and permanent. Today’s world is simply a continuation of that horror.

Title of the Kara Walker work above:

Bureau of Refugees: May 29 Richard Dick’s wife beaten with a

club by her employer. Richard remonstrated – in the night was

taken from his house and beaten with a buggy trace nearly to

death by his employer and 2 others.

2007

Cut paper on paper

30.75 x 20.375 inches

Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins and Co.

This entry was posted on November 8, 2007 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Extreme Interiors Olive Ayhens

Olive Ayhens expressionist nightmares of contemporary life currently on view in New York City at Frederieke Taylor Gallery are tour de force paintings that present us with the chaos of our contemporary world.

One recent series represented interiors of computer labs where the wiring has taken off on its own in a nightmare of disorder. At the same time, her paintings are detailed, complex compositions with bold offbeat color that jars the viewer. These cannot be passed by quickly, both because of their arresting content, their layers of details, and their complex formal devices.

Computer Lab 2005-2006 oil on canvas 52 x 61 incehs

This entry was posted on and is filed under Uncategorized.

Rashad Selim Iraqi artist in London

Baghdad Pavement 2006

“I have a sense of devastation within me. The works I have deal with devastation. ” Rashad Selim

“Art has to do with debris, breaking up, assymetry, loss of grammar. “

The layers of this collage include both old manuscripts which he has torn up and debris. Rashad is echoing the break up of both history and the present in his work.

He speaks of the corruption of language as in the word al Qaida which now means international terrorism, but actually means “fundamental base” in Arabic. It was appropriated by the CIA after 9/11.

“We don’t want to lose that last bit of humanity in a state of destitution.”

He speaks of the four dimensional war, that includes the destruction of the past, present and future. Depleted uranium is destroying the genetic pool of the future in Iraq.

“There is an absoluteness in this occupation that we have never seen before.”

Fragments from the Ministry of Justice, 2007

The large installation was constructed in London as a reference to the devestation in Baghdad.

Much of his work addresses symbols of unity such as the intersection of the star of David and Islamic pattern, the importance of symbolic numbers such as the six pointed star, seven eyes, and the circle, symbols that come from the Bible, Buddhism, and many other sources. Here also old manuscripts have been incorporated. Rashad is addressing the possibilities of unity, fertility, goodness and well beingn, as a counter to the divisive language of international politics.

Rashad is the nephew of Jewad Selim who created the Moument of Freedom in 1958. “It is a visual narrative of the 1958 Iraqi revolution told through symbols meant to protray a verse of Arabic poetetry. It is both modern and embedded in Assyrian and Babylonian wall-reliefs.”

( Strokes of Genius, 41)

This entry was posted on October 10, 2007 and is filed under Iraqi contemporary art.

Hanaa Malallah

“I am soaked in catastrophe like a sponge.”

“I am soaked in catastrophe like a sponge.”

So states Hanaa Malallah a major artist based in Baghdad who is currently in exile in London.

Hanaa Malallah is a prominent contemporary artist who has been teaching at the College of Fine Arts in Baghdad University until last fall ( October 2006), when she reluctantly left the city.

She said recently in London

“My work is about catastrophe. I am soaked in catastrophe like a sponge. I am stamped by Iraq’s wars.

During the Iran Iraq war I was 20. There has been war after war.

My pen is a knife. ”

This painting is called Baghdad City Map, 2007

The canvas has been burned and painted with black as a record of the destruction of the city. The one green star is a reference to the stars of the Iraq flag, the black stars refer to the US flag.This work is part of an ongoing series about Baghdad the city. Here is another one.

Hanaa survived the Iran Iraq War, the First Gulf War and most of the most recent war. She is a deeply committed artist who has left here city only to get the word out

“I didn’t want to leave my country. I want to do a project about the burning city so the world knows what I have seen. When I was in Iraq, every time I was in the street I had to know that I might die at any moment. I passed many dead people everyday, I took a minibus to work that had to follow long detours because the streets are blocked. Troops are everywhere. When I go shopping there are soldiers with guns pointed. I lived without electricity, water, little food, one hour of electricity if you are lucky. Hell is more comfortable than Iraq.

Baghdad was a beautiful city like London.”

She had major works on display in the Modern Museum in Baghdad which have now disappeared as have all of the works in the museum although the scholar Nada Shabout is working to locate them.

Each page of this large format book refers to Baghdad’s history and destruction. The City of Baghdad was laid out in a circle in by al Mansour in the mide 8th century AD at the founding of the Abbasid Dynasty. The Abbasids sponsored a flowering of Islamic culture for several centuries.

Each page of this large format book refers to Baghdad’s history and destruction. The City of Baghdad was laid out in a circle in by al Mansour in the mide 8th century AD at the founding of the Abbasid Dynasty. The Abbasids sponsored a flowering of Islamic culture for several centuries.

Ineffective Game I

Ineffective Game I

Anyone can play by moving the red squares around. Obviously it is a reference to the futility of the current situation in Baghdad, and the pointless games played by all participants. It is also a reference to the invention of games in ancient Mesopotamia such as the Royal Game of Ur.

Hanaa Malallah bases the pattern on the surface on the Sumerian patterns on pottery. She has studied the geometric principles of Islamic painting

and here disrupts that perfect order

The cone like projections are based on the ornamentation of the Temple of Warka in Iraq

Her generation of Iraqi artists emerged during the Iran Iraq war. They were unable to travel abroad, so they studied the history of Mesopotamia and incorporated references to archeological history in their contemporary paintings at the newly established Iraq Archeological Museum only steps away from the Institute of Fine Arts. For Hanaa Mal Allah the destruction of the archeological museum was a major part of the catastrophe of war, it was a place where she used to spend days studying the art. It is part of her heart and soul.

Hanaa wrote in Strokes of Genius Contemporary Iraqi Art, ed by Maysaloun Faraj Saqi Books 2001

“Those artists who choose to remain in Iraq despite all the obstacles are building new aesthetic and epistemological values in painting which are drawn entirely from the Iraqi reality with all its current influences and shifting sands.” (64)

For more images of Hanaa Malallah’s work see www.ayagallery.co.uk The Aya Gallery, London, which recently hosted a two person show with Hanaa Mal Allah and Rashad Selim . More on the art of Rashad Selim in another posting.

For a film on these artists see

http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/CD2E6527-E7A7-4CA5-A72F-FABB0A922828.htm

This entry was posted on October 2, 2007 and is filed under Hana Malallah, Iraq contemporary art in Baghdad.