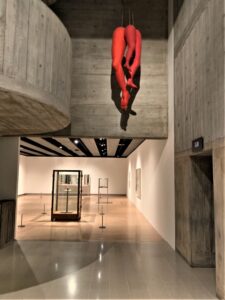

Beyond the Mountain at the Asian Art Museum

FOONG Ping, Foster Foundation Curator of Chinese Art here introduces her new show “Beyond the Mountain: Contemporary Chinese artists on the Classical Forms” to our press corps in Seattle. I have to warn you that I am a Ping groupie, I think she is really brilliant based on her lecture to members and her interpretations of the shows and installations she curates with Xiaojin Wu, the Curator of Japanese and Korean Art, and most recently with Natalia Di Pietrantonio, Seattle Art Museum’s first curator of South Asian art.

This particular exhibition has another exciting resonance, it was developed in collaboration with the students of “Exhibiting Chinese Art,” Spring 2020 Zoom seminar, University of Washington.

“Beyond the Mountain” gives us six contemporary Chinese artists who negotiate, alter and reinvent some of the deeply classical traditions of China. Ink painting is a central theme in two of the artists.

Ink/Protest

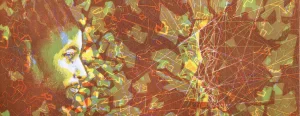

We begin with Chen-Shaoxiong (1962 – 2016) His video assembles hundreds of ink paintings of protests around the world, based on images he downloaded from the internet.

Here we have the most deeply revered technique of Chinese ink painting used to present the resistance to authority from Occupy Wall Street to Hong Kong. He depicts the protestors resisting police everywhere. the artist simply calls his works Ink Media, a clever ploy that ignores the imagery for authorities who might object?

The artist clearly has a dazzling facility with ink painting, but he is also deeply political. With Liang Juhui 梁矩辉 ( 1959-2006), Lin Yi Lin 林一林 (1964 ), the group Big Tail Elephant protested the rapidly urbanizing Southern city of Guangzhou with performance, photography, installations, and video placed in parks and other public places.

Landscape/Cityscape

The Departure

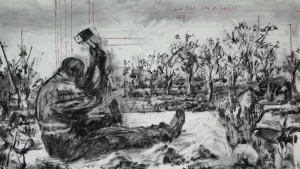

Yang-Yongliang evokes ink painting in state of the art digital works. Song dynasty monumental landscape paintings celebrated nature and the idea of slowly moving through it as we looked at the painting. Yang-Yongliang ( born in 1980) studied traditional Chinese painting. His videos, like Song landscapes, demand long slow viewing. As we look we begin to see that these are not natural mountains, but actually dense skyscrapers that build up into a mountain. A slow movement of water, as well as tiny people, and cars on highways, slows us down to wait for an event which never comes. We see the water flow, but it never arrives in the sea. we see the dog run, the man fish, the car arrive, but nothing happens, it is an event without an event.

As the press release states eloquently “The aesthetic expressions of old master paintings require close, patient attention to their rich detail, as they mimic traveling at a slow pace to places where the body cannot follow. The purpose of Song painting was twofold: rejuvenation—to relieve stress by countering the chaos of daily life with uplifting, virtual experiences of nature—and contemplation of human (in)significance in the face of nature’s inexorable forces. ”

But these paintings tell us a different story as we are mesmerized by their slow slow movement. We stop, we look, but now we see that while we are insignificantly small, we are destroying the earth. Here

I include an arm of a viewer to give a sense of the scale

the Return

artifact/culture

The gallery between these two experimental artists features two familiar works, one by AiWeiWei. Ai Wei Wei’s 2020 gesture in putting contemporary garish enamel colors on what appear to be old clay pots, is one of many of his outrageous acts over the years. It is less inflammatory than many though. For those of us who have followed his career for many years, this early work is pretty benign, but as you think about the reverence that classical pottery holds in China (perhaps not anymore, and certainly not during the Communist era when classical art was often destroyed) it still carries a lot of content. But if you are not Chinese, or versed in Chinese art, it might not come across as more than pots with bright paint messily applied.

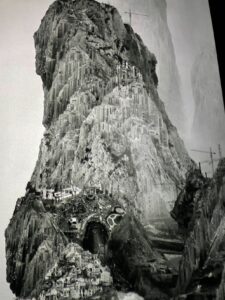

The other work by Zhang Huan. “To Add One Meter to an Anonymous

Mountain,” 1995 is a well known early work by a well known artist.

He piled up bodies on a mountain and added one meter to a vast landscape, again suggesting the insignificance of humans in the scale of nature and the Chinese proverb “Beyond the mountain, there are higher mountains yet,”

landscape/escape

The final room of the exhibition by Lam Tung Pang is by far the most

difficult to understand. Created during the pandemic, it is about being isolated and enclosed and finding a means of escape through fantasy, imagination, and technology. An enclosed space that we are not allowed to enter has a projector that sends various images onto the walls of the enclosure as well as around the room. we become part of the show sometimes. Images include someone gazing at a huge ball of sun or earth, a girl riding a blind-folded donkey, a goose plummeting to the ground ( you can barely see that here) and many other elusive details.

Two other works in the room suggest space flight, Someone a Day 521

and crashing into a mountain, in Echo ( a tiny astronaut is suspended from the ceiling and his shadow appears on the mountain)

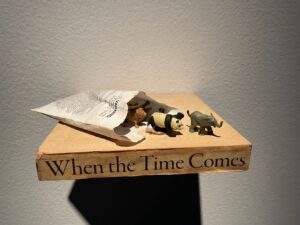

and a 2013 work called “When the Time Comes” features a type of bizarre Noah’s ark image of animals marching out of an envelope

All together the installation suggests anxiety, instability, and a search for something solid. It feels like the isolation of the pandemic left the artist floating in mid air like the astronaut that approaches Echo

The exhibition as a whole provokes us with its dialog with history, but most of all it speaks to the present and our current planetary crisis. Disruption of history is where we are now, and destruction of the planet is ongoing. Our small presence within this extraordinary home of ours is creating an outsized impact.

This entry was posted on August 30, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Artists on Fire: Deborah Faye Lawrence and Nancy Kiefer

Hats off to Bonfire Gallery for another cutting-edge exhibition with two of the most outrageous artists in Seattle. Deborah Faye Lawrence and Nancy Kiefer both push the boundaries of what is acceptable, but in strikingly different ways.

The title “Still Hung Up,” refers to a phrase that used to refer to passionate affairs gone wrong. But now it means the artists’ obsession with creativity.

Nancy Kiefer Eye Rise 22” x 30” mixed media in paper

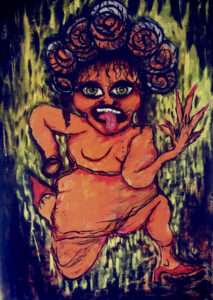

Nancy Kiefer has a long career of creating insanely confrontational, close up images of women. They are sassy, angry, beautiful, naughty and, recently, tragic in her mothers of the disappeared from her “Fierce Woman” series. These are not easy to look at, the colors are harsh, highly saturated and discordant. Kiefer’s use of black line is aggressive.

But what immediately almost overwhelms us is the power of all of these women, whether they undulate like a flame as in “Eye Rise,”

Nancy Kiefer Gorgon (protector)Oil on canvas

offer protection with a flip of a long nailed hand in “Gorgon (Protector)”,

Puppet Oil on wood 12” x 9”Nancy Kiefer

or hold a terrifying witch mask in “Puppet.”

More anguished are the faces of the mothers of the disappeared: they convey a psychological reality of screaming suffering with gaping mouths, yellow streams that could be tears flowing from all directions, wisps of white cross a face like a ghost passing.

Kiefer is a storyteller as well as a painter, and we see stories in these faces. She exposes the grotesque in our public world with these private women. I am reminded of both Jean-Michel Basquiat’s rawness and Picasso’s portraits that layer emotional states from outside to inside. But Kiefer boldly strips away the outside and gives us only the inside and it is, of course, also her own intense emotional experiences that inform these works.

Deborah Faye Lawrence disrupts us with collaged images that create unexpected juxtapositions paired with an intense choice of words and references. Like Kiefer, her women are strong and naughty. In “Hen Party” four rooster headed acrobats perch on others only partially seen. They triumphantly hold at bay an intense onslaught of pointed streamers from every direction, each with a different barbed expletive for women.

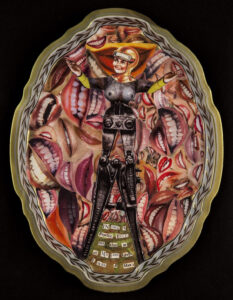

“Psychic Revolution” features a busty woman built up from multiple robot-like pieces. She holds out her arms as if to present herself to us but she also holds at bay dozens of smiling teeth filled mouths.

Lawrence frequently uses tin tv trays as the ground for her complex collages. The oval format reinforces the image of the many crescent shaped mouths. The text, collaged from cut out words, reads “In 1985 a psychic told me that in all my past lives I was a man.” So we see the figure at the center now as androgynous and dominating all the teeth and mouths out to eat her up.

In “Fluid Self Portrait,” another collage on a tray, a 1950s woman with pearls and heavy glasses balances spherical wooden tops on two fingers of each hand. Her body is an unstable stack of plates balanced on another top, in a landscape of tops. The whole suggests an impossible situation even as the woman beams a huge cheerful smile. The message is clear.

Lawrence has been making powerful collages for decades. She addresses specific political events, feminism, and personal history, as she undermines cliches and takes on causes. Her sardonic humor wakes us up.

BONFIRE’s small gallery in the International District explodes with feminist energy. These intense artworks show us how to resist the multiple abuses of women’ rights world-wide. Here in our country, of course. we have the imminent loss of the right to an abortion.

These artists tell us we are already angry and outrageous, now we need to act on it!

This entry was posted on August 25, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.

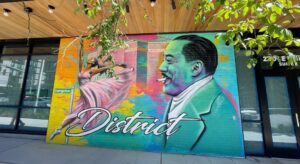

Midtown Square: The Public Art Display!

“Midtown Square at 23rd and Union is a major destination for outstanding public art.

The overall theme of all the panels is “Reverence and Discovery.” Although not planned, all the art work is unified by similar colors such as purple, yellow, orange, pink, black.

Barry Johnson specifically explains why he chose the unusual colors for the abstract panels on Union Street near 23rd street:

“This work on the outside of the building is about overcoming a documented history of red-lining in the Central District. I used lines and movement at the forefront of the design as a way to demonstrate how we’ve moved beyond the confinement that was placed around us. The lines are also a head nod to pathways that slaves would use to escape. The bold change in colors are about injecting new perspectives into the city. Black and Brown people have not been given opportunities to offer our views on Architectural Design across the city. Seattle is mostly composed of greens, tans, reds and orange for building colors, so I wanted to do something that was completely different and challenge every colorway used on a building in the city.”

Hanging below Barry Johnson’s brightly colored panels, Yegizaw Michael creates a Central District timeline with similar colors alternating with patterns in hanging strips of wood.

On this same façade Adam Jabari Jefferson chose to create black and white photo-based murals with in large vertical strips: “Been Here” “Neighborly Day” “Land Earth Legacy.” As he writes

“The images explore connectivity to both land (the Central District) and community. As the CD demographics continue to shift, these portraits are a declaration by the dispersed social networks that composed the neighborhood, by necessity, for generations. We are still here. Digital photography and mixed media comprise the series to portray iconic and dignified people.”

James W. Washington, Jr.

Not far away is the restored James W. Washington, Jr sculpture “Fountain of Triumph.”

Barry Johnson also created the bronze portrait statue of James W. Washington Jr.. Johnson’s sculpture of Washington holding a small carving of a bird, one of his characteristic expressions. He faces the restored Washington sculpture, “Fountain of Triumph” which was originally installed on 23rd and Union.

Washington explained:

“As the salmon starts back on its physical trend to complete the cycle where life began, so it is with Blacks of the racial trend on the American scene who have struggled like the salmon to reach his or her pinnacle of life and the free spirit again . . . This is the goal of the African-American women and men: To pass on to their offspring the energy in their body and recycle their physical remains in Mother Earth to be used again.”

Near to Johnson’s statue of James W. Washington Jr., is the metal sculpture by Juan Alonzo of four leafy hollyhocks that climb up the wall. Alonzo honors a native plant of the community with the poem “In once neglected soil /I will thrive Because I am deeply rooted here/ I was able to grow tall and strong.”

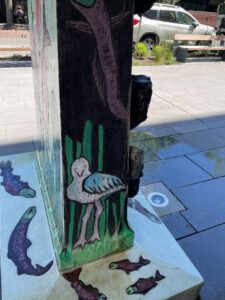

As we walk along 24th avenue we come to an entrance into the central square with a mural by Perry Rhoden that leads us into it.

She tells us what she was thinking about as she painted it:

“The doorway into the Square from 24th Avenue is similar to the first impression you experience when walking into someone’s home for the first or one-thousandth time. The energy of the home fills your body with peace, warmth, and belonging. This is the feeling I want the community to experience when they enter the Square.

The large abstract lines sweep from the base of the mural and move the viewer’s attention deeper into the corridor. The lines vary in width and color to create dimension and pattern. I focus on bright and bold colors. Placement of the lines will cause the viewer to question whether the woman is inhaling or exhaling ultimately drawing viewers into the square.

I want to create this mural as a visual reminder to breathe. Breathing centers me to the present when I am reminded of how gentrification has changed the Central District. Breathing is what empowers us to accomplish even the most unfathomable tasks. Breathing calms the central nervous system. And, we have the ability to breathe new life into the future of this corner.”

Following Perry’s mural, we enter the Central Square where the huge mural by Takiyah Ward stretches across the entire facing wall. It is a tour de force by an artist who like Perry Rhoden, was part of the team that created the Black Lives Matter mural on Pine Street during the Occupy movement (you can still see it there).

Takiyah Ward describes her striking mural in the central courtyard of Midtown Square as follows:

I consider this mural a visual timeline of the history of the land. The story is told from right to left, North to South, past to present. And it begins with the land. Next, you notice a portrait of Chief Seattle as representation of the Indigenous people being the first people of this land. From there we travel through time to the present, highlighting the people, places and events that I felt played impactful roles on the trajectory of the Central District. As someone born and raised in Seattle, I have my own history here. I did much research to build a thread that to me made sense and highlighted the colorful history of the CD.

The figures are ingrained in the mountain range background, a local Mt Rushmore if you will. The midground, or hills, are decorated with places or centers of community that are pivotal to the peoples lives. Finally the foreground or low hills are covered in visual depictions of events that represent an illustrious history of art, culture, activism, and accomplishment. My goal with this mural was to spark conversation and curiosity. To be a beacon of reverence for our past, cement our history and ensure it’s never forgotten.

Traversing another passage leading from the main square to 23rd street, we see glass lanterns above our heads. Henry Jackson-Spieker in collaboration with KT Hancock lanterns ornamented them with portraits and icons referring to historic figures such as artists James W. Washington. Jr., Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight and the photographer Al Smith, along with musicians and other cultural contributors.

And finally, as we turn north along the façade on 23rd street, we see the vivid portraits by the artist Myron Curry.

Here is his description:

I’m born and raised in the Central District so I am familiar with a few of the iconic community members from our past. I am also very proud to be a part of a project that highlights our culture in such a vibrant way. My grandfather is 91 and has lived in the Central District for the majority of his lifetime. He was very instrumental in my extensive research and discovering so much more about the history of the Central District.

I definitely wanted to highlight the thriving arts and music scene as well as the pioneers of equitable rights and entrepreneurship. Edwin Pratt, Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center, Jimmy Hendrix and Ernestine Anderson were perfect for the development of historic arts and music within our community. De Charlene was an obvious choice for pioneering so much change in equality, black woman entrepreneurship and more. I also wanted to include the youth, which is our future and how we need to nurture them.

My creation to visually represent this was loving hands holding a baby. I hope this sheds some light on how I chose who to represent within my murals.”

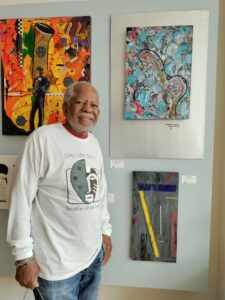

Gallery Onyx

Gallery Onyx Midtown will be anchoring the ArteNoir space,adding a second venue to its Pacific Place anchor. Headed by Ernest Thomas, the first exhibition will be based on their portfolio of art by Pacific Northwest, Truth B Told showcasing 276 pieces of artwork by 74 artists of African descent. Gallery Onyx believes in inclusivity on a grand scale! But the plan is to also begin a new direction with one person exhibitions.

So the vision to create sustainable community through art comes alive at Midtown Square in multiple ways. Yet there is also a poignancy to this magnificent project that includes so many different cultural expressions as a way to reassert the African American presence in this historic location.

Arté Noir is a distinct contrast to the former businesses of the Central District. It is a new and stunning expression of contemporary Black culture today. But it embraces history even as it transforms it.

Across the street from Midtown Square, the Liberty Bank Building is another success in revitalizing the Central District with its many works of public art and thriving black businesses. Here is the stunning entrance with Al Doggett’s amazing mural.

Realized by Africatown-Central District Preservation and Development Association, who are committed to community-led development, the same group is developing one quarter of the Midtown Square block.

The site is under construction. At the dedication Africatown leaders declared:

“Africatown Plaza will continue a legacy of community building on the site of the former Umoja PEACE Center, the grassroots, Black-led community organization where the Africatown Seattle movement began over a decade ago.”

Most of the participants in this project grew up here. They know what they have lost. They recognize that this new iteration is not the same as what they remember. But they do believe in community, and in that idea there is hope that this part of the city of Seattle can keep its soul.

This entry was posted on August 23, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.

A Visit to South Africa by Pamela Allara and the new opera Sibyl by William Kentridge

Professor Kim Berman and Pontsho Sikhosansa work on a Ramarutha Makoba print in the Newtown studios. Photo supplied

Some background information: in the 1980s, when I taught modern art history at Tufts, I was the academic advisor for the students in the MFA program at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. One of my students, Kim Berman, was from Johannesburg and she was very active in the anti-apartheid movement. Through her, I became interested in activist art, and contemporary South African art in general,

In 2000 I was appointed to teach at the Johannesburg Technikon. I have returned every year since for research, writing, and curating. Obviously, no trip was possible last year, so I was especially excited to travel again, for two weeks this past April.

Susan has asked me to discuss my visit to William Kentridge’s studio, which took place right before I left, but I cannot resist briefly showing a few other highlights. One was an exhibition at the Goodman Gallery of the wire sculpture of Walter Oltmann, “Armour and Lace: A Bestiary”. In the photo above , Walter is on the right; David Paton, Kim’s colleague at University of Johannesburg on the left; I’m in the center.

Walter taught for many years at Pretoria University, and has recently retired early. Retirement is encouraged by age 65, as the South African government is eager to make way for non-white faculty.

Back in 2003, I included one of his life-sized standing armored figures in the Co-existence exhibition I curated at Brandeis’ Rose Art Museum). He is still working with those figures, although as the title suggests, he has also turned to wire lizards and other flora and fauna in wire reliefs. As always, the sheer volume of the labor involved was mind-blowing

I also visited Usha Seejarim’s studio on the other side of Johannesburg. Her studio does not seem spacious, but perhaps that is because her work is large. A line of red and yellow threads spread about 20 feet across the floor, which will be installed in the arts festival in Grahamstown, South Africa in June. Lying on the floor next to the thread piece were charming ‘spiders’ made from one iron plate with thin metal legs attached.

She is also constructing, with the help of one of her assistants, 8 metal models of the clothes peg, each about a foot high, that will be sold to cover the costs of fabrication and shipping of “The Resurrection of the Clothes Peg”, which will be the centerpiece of the Burning Man Festival in Nevada in July.

Her work draws from domestic objects like irons and clothes pegs . As she explained in a conversation with Robert Preece in Sculpture magazine

” The domestic objects in my work are, for me, somewhat metaphorical; I think about their function. For example, the clothes iron smooths out creases; its function is to make a shirt or other item of clothing neat and presentable. The clothes peg holds, clasps, grips, and embraces; the broom sweeps away dirt and clears a space. I am aware of how these objects and their use are associated with a female role. Thus, they become quite genderized. I have come to recognize the particular triangular shape of the iron and how that shape has a feminist/vaginal reference. So, the works do not refer to a specific context as much as they refer to the notion of domestic roles and how they are—historically, culturally, socially—assigned to or claimed by the female. I would like to think of these forms as universal symbols understood around the world.”

Usha was just back from Lagos, where the work is being fabricated. The final work will be about 40 feet high, and the most monumental piece at BM. She is now trying desperately to get a visa so she can be there for the opening.

Now on to the visit to William Kentridge’s studio. Kentridge is, of course, South Africa’s most well-known artist; recently, he has received The Queen Sonja Lifetime Achievement Award from the Queen Sonja Art Foundation in Norway. Kentridge also is a long-time friend of Kim Berman.

After her MFA studies in Boston, Berman founded the community printmaking studio, Artist Proof Studio, in Johannesburg in 1991. It is now a thriving center, offering classes in printmaking and professional printing services to artists such as Bokang Mankoe.

APS had been downtown, but the city wanted its convenient location for its offices, so moved it lock, stock and barrel to a fancy shopping center. So the students must take a daily hike from the public transport downtown. Because it was a holiday, only two of the printers were there when I arrived.

Kim and Nathi Ndladla, the head of the studio, were working on the giant Kentridge print, “You Who Never Arrived,” with its forest of trees. The work consists of about 12 prints attached to handmade paper that is then affixed to cloth, becoming a sort of tapestry. I was nervous about the two of them filling in the blanks across the spaces between the individual prints and touching up the trees with black ink, but Nathi and Kim clearly enjoyed themselves.

The next day Nathi, who had the Kentridge hangings carefully wrapped, drove me to William Kentridge’s house in the suburb of Houghton so he could sign them. I was sure that the source of his imagery was one of the trees on his property, but when I looked around I was clearly wrong.

William’s son had been married there in the garden the day before, and clean up was taking place. William was leaving for exhibits in London and Lucerne that evening, but took the time to show us the new video that will accompany a performance of Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony by the London Symphony Orchestra (I think).

He also showed me the notebook where he jots down the quotes and phrases he uses in his artworks. He was remarkably gracious, given his tight schedule, but this is true of South Africans in general. Also remarkable is the lack of ‘artistic ego.’ After all, he is South Africa’s most well-known artist, with a huge retrospective planned in London next year. But clearly, he considered Kim and Nathi to be colleagues. I may be wrong, but I think many successful American artists would consider their assistants to be just that: assistants. Not the case here, another reason why I enjoy going to South Africa and writing about the art there.

The political situation in South Africa is not the greatest at present, as Cyril Ramaphosa’s government is rife with corruption. The situation is also dire with museums; for example, the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s facilities are in terrible shape, with the collection in jeopardy. And yet, artists continue on, and good work continues to be made. Their continuing productivity is a source of hope in grim times.

Kentridge lives in the house he grew up in. His father, Sir Sidney Kentridge, defended Nelson Mandela in the Treason Trials that sent Mandela to prison for 27 yrs. His studio is the former garage on the property, now quite transformed! The collage of flowers and plants on the end wall of the studio he made for his daughter’s wedding a year ago, and re-installed for his son’s wedding, which had taken place the day before we arrived.

____

Afterword by Susan

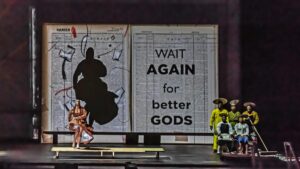

I was very fortunate to see the London premier of William Kentridge’s opera Sibyl at the Barbican.

The artist himself was there in the audience!

Here is the only photo I was permitted to take of the theater screen before it began

Here is great clip

From The Times Review Donald Hutera

Monday April 25 2022, 12.00pm, The Times

“The South African visual artist William Kentridge’s Sibyl is an extraordinary achievement, no matter how you categorise it. The work comes in two parts: an approximately 20-minute film accompanied by live piano and male chorus and, at double that length, a ritualistic chamber opera (originally commissioned by Teatro dell’Opera di Roma and created between 2016 and 2019) featuring more music, song and dance and the kind of multilayered stage imagery in which Kentridge specialises. To call it stimulating would be an understatement. It is also cumulatively, and sometimes almost inexplicably, moving.”

Here is a You Tube clip

It was a multimedia extravaganza of music, dance, costume, all performed by South Africans of incredible skill.

The theme was the unpredictability of trying to predict the future. The Cumaen Sibyl was a fortune teller who threw fortunes out at random on oak leaves and people had to figure out which was theirs, a metaphor for the unpredictablity of life and knowing the future. So the opera had a lot of paper flying around, lots of fortunes.

But it also refers to our contemporary efforts to predict the future with algorithms

As one anonymous analysis explained

“Unspoken throughout but hovering over the opera is the notion that our contemporary Sibyl is the algorithm that will predict our future, our health, whether we’ll get a bank loan, whether we’ll live to 80, what our genetics will be. This certainty of an implacable mechanism that determines our outcome is juxtaposed against the desire for a more human connection to our destiny, an instinct to believe in the possibility of something other than the machine to guide us in how we see our future. The work is a profound, jarring, playful, and visually stunning meditation on what it means to be alive in our current moment in history, grappling afresh with humanity’s primordial task of making sense of the inherently tragic state of always knowing, yet never knowing, where our end will lead us; the cursed and blessed consciousness that makes us human.”

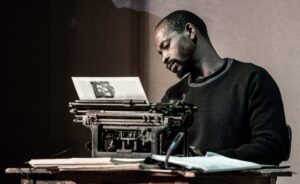

The evening began with a 22 minute silent black and white film The City Deep with choral director and dancer Nhlanhla Mahlangu leading a chorus of nine performers and and Kyle Shepherd, a leading progressive piano player from South Africa. Above is a still from a the Kentridge film, The City Deep

As explained by the Goodman Gallery in NYC ( where you can see drawings for the film)

“In City Deep, the artist’s unique charcoal animation technique of successive erasure and redrawing conjures a non-linear story featuring his drawn alter ego Soho Eckstein, set between a municipal art museum (based on the Johannesburg Art Gallery) and an abandoned mining area at the edges of the city where unofficial artisanal gold mining takes place.

” The action jumps: the museum collapses, Soho comes face to face with his fate, whilst a solitary miner persistently works against his destiny. Interspersed throughout are images of the film’s creation, of the artist in his studio—always itself an action (a futile one) against destiny.”

” City Deep is the anticipated 11th film in Kentridge’s Drawings for Projection series, a collection of animated films drawn over 30 years, featuring the protagonist Soho Eckstein. South Africa’s political transition from the violent years of apartheid to democracy sets the scene for a saga of loss, love, anger, compassion, guilt and forgiveness. The films revolve around the power-hungry mining magnate Soho Eckstein, his wife Mrs. Eckstein and her lover, the solitary artist Felix Teitlebaum. As the story unfolds, Soho’s empire crumbles as he comes to terms with his own frailties and the first signs of mortality.

” Like previous films in the series, City Deep is grounded within Kentridge’s home city of Johannesburg and can be viewed as a counterpoint to the 1990 film, Mine, which depicts images of the deep level mining industry.

City Deep extends this depiction to the informal, surface-level “zama zama” miners of current day Johannesburg. Translated from Zulu as ‘try your luck’ or ‘take a chance’, “zama zama” is the name given to the miners who illegally work decommissioned mines on the edges of the formal mining economy. Manual labour replaces large machines, creating open scars in the Highveld landscape.

In City Deep, the “zama zama” miners and the landscape merge into artworks hanging in the Johannesburg Art Gallery, itself built during the heyday of gold mining in Johannesburg. Wandering the exhibition spaces is a deeply contemplative Soho gazing at the artworks and into vitrines. Towards the end of the film the gallery collapses in on itself, an imagined demise of an institution in a state of increasing dereliction.

The second part of the evening featured Waiting for the Sibyl, the opera. During the pandemic Kentridge published the libretto.

As Kentridge explains:

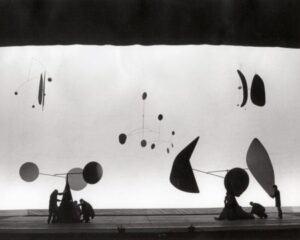

“The project at Rome Opera, Waiting for the Sibyl, comes from an invitation from the opera house to make a companion piece to the 1968 piece by the American artist Alexander Calder, called Work in Progress. The 1968 piece is a beautiful, whimsical almost-happening of the era, with mobiles slowly turning on the stage, and groups of bicycle riders; but the signature mobiles of Alexander Calder are the heart of the piece.

In responding to the invitation to do a second half of the evening, I wanted something that also had a sense of turning, of revolution, and of the lightness of the Calder. I was reminded of the image of the Cumaean Sibyl. My understanding of her story was that she lived in her cave near Naples; people would come to her with questions about their fate, and she would write the answers on oak leaves. There would be a pile of oak leaves at the front of her cave and people would come to get their answers.

But inevitably there would be a wind which blew the leaves around – so you never knew if you were getting your fate or somebody else’s fate. It’s a beautiful metaphor of not being able to predict our futures. This idea of leaves blowing and turning, and uncertainty, became the connecting point for Calder’s moving, turning mobiles and something that grounds the piece with that turning but hooks into questions that I’m interested in today.”

Photo by Yasuko Kagayama

“I was thinking about the theme of fate and our future and the telling of our future, as the Sibyls did; this meets the work of Alexander Calder; and both of these come together in the material ways of working to make the piece.

photo Stella Oliver

The idea of turning leaves into pages, and the pages swirling around, brought together the turning sculptures of Calder, and the pages on which I had been obsessively drawing in the service of making films out of books. Part of the form became the projections of the texts and the drawings in the book and the shadow made in the book by the performer of the Sibyl. Different scenes were added. A scene in the waiting room for the Sibyl. A scene about which is the right decision and which is the wrong one. How do you know which is the chair that will collapse when you sit on it and which is the chair that will support you?”

There were a lot of people sitting on collapsing chairs in the opera. The multimedia made it overwhelming, stunning piano, singing, film, dance, costumes. The odd flat discs on people’s heads I finally figured out connected to the Alexander Calder

Here is another excellent You Tube video from the rehearsal for the original performance in Teatro dell’Opera Rome, September 2019, before the pandemic delayed it.

Even in the stills you can see the layers of complexity!

Photos by Stella Oliver and Yasuko Kasegama

This entry was posted on June 14, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Louise Bourgeois Goes Way Beyond Anyone Else

Louise Bourgeois affects us viscerally. The extraordinary physicality of her work outstrips any other art addressing the female body and its excruciating alterations from pregnancy, childbirth, parenting, sexuality, abuse, aging.

I once met her in Houston at a conference of women artists who were marching for the ERA in 1975. She was wearing a many breasted Artemis dress.

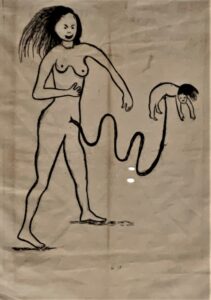

But the works in “Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child.” at the Hayward Gallery, begun so many years later are not at all entertaining. They are not easy. This print is called Umbilical Cord dated 2000.

I felt drained after viewing this exhibition It looks at her works using textiles that she began only in the mid 1990s when she was already in her eighties. We were thinking Oh textiles, pretty benign. But of course it was the opposite.

The first piece we saw as we entered the gallery suggests the process of the artist in creating these works. Apparently in the mid 90s she asked her assistant to bring all her old clothes down to her studio.

Of course her old clothes are a lot more interesting than our old clothes. Old fashioned undergarments hang on hangers or odd large bones in a “cell”, as Bourgeois tellingly calls this type of installation marked private.

At the center of the cell is a small spiral staircase with a bed and a body from which threads emerge. If you look hard you will see a spider also.

As we went further into the exhibition we saw more old fashioned underwear now hanging on bones in the gallery, not in a cell. It was somehow more frightening that way.

In the next segment was another famous and terrifying work: the famous spider installation from 1997. A huge spider, called Maman, nine meters high, was featured in the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern when it opened in 1999, and again was displayed outside in 2007 during a major retrospective of the artists work. According to the artist ‘The Spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver … (she) was very clever. Spiders are friendly presences that eat mosquitoes. We know that mosquitoes spread diseases and are therefore unwanted. So, spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother.”

In addition spiders spin threads, and repair their webs when we destroy them. But they can also swallow insects easily.

In this version of Spider there are fragments of tapestry inside as well as other details of sewing. As we all know, Bourgeois worked for her family restoring tapestries as a child. She worked on details such as hands or feet. Here we see the spider that spins thread turns into a giant predator.

From the catalog essay “Weaving Materials and Metaphors,” by Lynn Cooke

“While the spider and unspooling thread were freighted with

personal signification for Bourgeois, both are replete with classical

allusions as she doubtless knew. In Metamorphoses, Ovid

provides an aetiology for the former in the tale of Arachne who

foolishly contested Athena’s pre-eminence in the art of weaving.

Enraged that she had been bested, the goddess transformed the

upstart maiden into a spider bound forever to spin and weave.

Thread lies also at the heart of a haunting myth featuring the

Three Fates who control the destinies of mortals. In Hesiod’s

version, Clotho, the spinner, Lachesis, the allotter, and Atropos,

‘the inflexible one’, who terminates each human life with an irreparable snip of her scissors, all take the form of old women.”

Another installation Needle 1992 The gigantic weaving needle arcs from hanging yarn that spools on the floor. It has had an unavoidable sexual reference of invasion, but who is invading what. The oval shapes maybe ovaries? The sheer audacity of the piece is thrilling.

The exhibition included several series based on smaller embroidered works. As always, you think oh, small scale, but then pow.

Many of the works were figurative. Here is the incredible image of childbirth at the top of the post : Do Not Abandon Me 1992

These images really speak for themselves. They are all untitled.

1996

1996

2007

2005

1996

1996

1996

There were many other works in the exhibition, such as this one called Endless Pursuit from 2000.

Or this one Cell xxi 2000 and you see other cells aligned with it behind it.

The famous spiral woman 2003 but it exists in many variations of course. She looks like she is experiencing multiple pregnancies

Particularly painful Knife Figure 2002

The Mute 2002

And much much more. Incredible bodies intertwined missing some parts such as heads. Anonymous copulating that feels as though the two bodies are one single organism. For some reason I didn’t take pictures of those. Perhaps because they were all black and too dark in both their color and their mood.

A great deal has been written about Louise Bourgeois and she wrote a great deal herself. But in the end I am speechless at the sheer physicality of her work. So the woven head of the mute seems to be an appropriate ending.

This entry was posted on June 2, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.

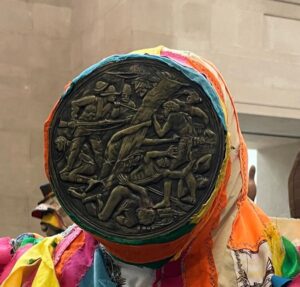

Hew Locke “The Procession” at the Tate Britain

On our trip to London one of the most exciting experiences was seeing Hew Locke’s “Procession”

filling the central court of the Tate Britain with its brilliant collaged figures entirely constructed from recycled materials.

The Tate is on the site of a former prison, which I wrote about in 2017. Now we see it as the product of capitalism and specifically the exploitation of black labor in the sugar industry. Henry Tate was a sugar magnate.

Hew Locke: The Procession “What I try to do in my work is mix ideas of attraction and ideas of discomfort-colourful and attractive but strangely, scarily surreal at the same time.”

The Procession has 150 figures, no two are the same

It includes painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture. It is entirely imaginary, there is no particular culture or mask quoted. The Procession can be almost a funeral.

Celebration, worship, protest, mourning, escape Imaginary people

Starting point Henry Tate, sugar refining magnate. “reflect on the cycles of history and the ebb and flow of cultures, people, finance and power.”

Note the pants on this figure. It is the famous image of the Middle Passage

The famous Back to Africa movement led by Marcus Garvey used these certificates for joining

The artist bought shares from dead companies included the Black Star line.

Text below is from Tate:

“The figures travel through

space but also through time. They carry historical and cultural baggage: the evidence of global financial and violent colonial control embellishes their clothes and banners.

This figure with the striped dress has a cat head. See next image

“Images of the colonial architecture of Locke’s childhood Guyana emblazon the flags and their bearers, its flooded fields and rotten wooden walls vanishing under rising sea levels. Despite this, their attire and stance suggest power and self-assertion.

Chest labelled East Indies Sugar

Locke occupies a space that was founded from wealth derived form an industry built on the labour of enslaved African people and their descendants and which subsequently relied on the indentured labour of Asian people”

Here is a misshapen globe

Locke says he “Makes links with the historical after-effects of the sugar business, almost drawing it out of the walls of the building.”

“The Procession” also carries Locke’s own past artistic journey with imagery linked to his previous work incorporating statues, rising sea levels, Carnival and the military.

Leonardo self portrait inside the niche. Cut up Benjamin West painting on another

“While being marked by history, The Procession’s participants are not constrained by it. These fragments come together to usher new meanings and sensations, stirring collective memories, fears and desires.”

“The work evokes real events and histories and yet presents them as aesthetic fiction. As we join “The Procession” and Locke’s artistic imagination begins to work on us, the figures invite us to walk alongside them for a while, into an enlarged vision of an imagined future.”

“The influences of both Indian and Indo-Caribbean culture can be seen in The Procession, as in much of Locke’s work to date. It is unclear whether the procession participants are wearing masks or if these are their true faces. Several figures and costumes within the Procession reference specific Caribbean Carnival characters from across the region.

These include Mother Sally in her voluminous dress, Midnight Robber, wearing a huge brimmed hat, Pitchy Patchy, dressed in a suit made of tattered, colourful pieces of cloth and Sailor Mas, inspired by British, French and American naval staff. Each has its histories and its portrayal differs across the Caribbean”

Churchill statue in background that artist has covered with graffiti

This suggests the climate crisis another Locke theme

I will stop here. It is impossible to actually take it all in.

This entry was posted on May 30, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.

The Stonehenge Exhibition at the British Museum

Right after we arrived in London, we went to the Stonehenge exhibition at the British Museum. I got free press passes for me, Henry and Henry’s sister, Imogen.

There were so many amazing aspects to this display that it is impossible to convey the depth and extent of the experience. Not to mention the complexity of the information provided.

Stonehenge was constructed at around the same time, 4,500 years ago, as the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt.

The exhibition spanned the

Mesolithic (c. 12,000–6,000 years ago),

the Neolithic (c. 6,000–4,500 years

ago) and

the Bronze Age (c. 4,500–2,800 years ago).

Here is the first image in the Stonehenge exhibition at the British Museum. I took a still from the video that shows how many Neolithic sites have been found in the United Kingdom. The exhibition also includes work from Europe. This photo shows most of the 1300 sites discovered in the UK, it does not include Brittainy. The first alignments with the solstice have been located as dating to 3700 BC

“Stonehenge’s significance changed enormously about 4,000 years ago, as it gradually became the central point around which hundreds of burial mounds were raised. Across Britain and Ireland during this period the importance of death and the role of grave goods in expressing ideas and identities reached its peak” cat p. 20)

The early societies were connected to nature, to the heavens and to one another.

There was an overall trajectory from peaceful, celestial worshipping communities, to, farmers, to guess what, social hierarchies based on wealth and then marking territory and warfare. the transition from stone to metal was a key moment for the change from communal society to individualism.

A polished axe made from porcellanite from County Antrim, Northern ireland, and deposited in a bog c. 3500–3000 BC Shulishader, isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland Porcellanite stone and rosaceous wood (hawthorn or apple),

Beautiful display of stone axes.

Seahenge wooden circle found in Norfolk created 2900BC

In situ Seahenge Norfolk 1998 copyright David Robertson

I realized as I was writing this that I visited a Neolithic burial site with my 87 year old mother in law in 1995 at Barclodiad y Gawres (Welsh for “The Giantess’s Apronful”) near Aberffraw in Anglesey

Necklaces ivory bone and tusk Finds from Skara Brae, c. 3100–2500 BC Skara Brae, mainland, orkney, Scotland

The Knowth decorated mace-head, Flint c. 3500–3000 BC Knowth, County Meath, Republic of Ireland

Elaborate relief incised into flint. These extraordinary objects were so beautifully displayed!

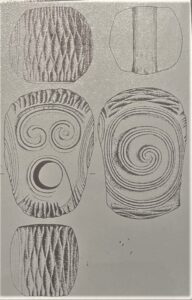

The Towie decorated and carved stone balls, c. 3000 BC Towie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland Stone, diam. 7.3 cm National Museums Scotland,

These incised stones were found in the open air, not in a burial.

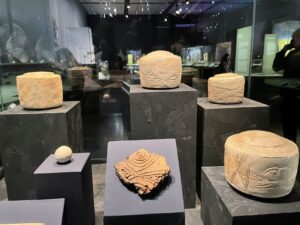

the Folkton ‘drums’ or cylinders, found with the burial of a child, c. 3000 BC Folkton, north Yorkshire, england Chalk, H. 11.9 cm, diam. 14.4 cm (largest piece), H. 8.3 cm, diam. 10 cm (smallest piece) British museum, 1893

Now we move on to the age of metal and gold, a significant change in the society. Status comes in!

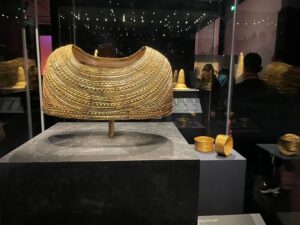

Lunula, 2400–2000 BC Blessington, County Wicklow, Republic of Ireland Gold, diam. 22.1 cm British Museum, WG.31 Donated by John Pierpont Morgan

The Mariesminde hoard, c. 1000–700 BC Mariesminde Mose, Funen Island, Denmark Bronze and gold, H. 20.5 cm, W. 14 cm (each cup), H. 35 cm, W. 42 cm (vessel) National Museum of Denmark,

Those conical bronze shapes on the wall were placed on women’s stomachs in Scandianavian graves. THey are covered with symbols of sirals and sun motifs symbolizing regeneration and rebirth. The connical shape represents the center point of the sun’s power.

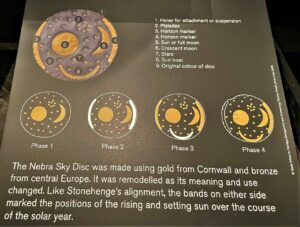

Here is the most exciting and beautiful piece in the exhibition!

The nebra sky disc, buried c. 1600 BC nebra, saxony-Anhalt, Germany Gold and bronze, diam. 32 cm state offi ce for Heritage Management and Archaeology saxony-Anhalt, Halle, Hk

This sky disc was one of the most exciting pieces in the exhibition

It gives us the subtlety of the early understanding of constellations, and in its materials, speaks of the exchange of goods over long distances, It included bronze from Central Europe.

Axe heads 1700–1500 BC Arreton Down, Isle of Wight, England Bronze, L. 17.2 cm, W. 9.9 cm

Spiritual Warriors on Serpent headed boat

Horns and bells , bronze, Dowris hoard, 950–750 BC County Offaly, Republic of Ireland

Shields, bronze, Isis River, oxfordshire, england diam. 34 cm British Museum, Rhyd-y-Gorse, Ceredigion, Wales, British Museum,

the grim conclusion of a battlefield

The British Museum did a stunning job of installing, sequencing, and explaining these sometimes esoteric objects. They carefully gave equal privilege to the humble works of ax heads and the gold necklaces. They also gave us a sense of what holds a society together ( a shared belief system) and what makes it fall apart, land cultivation, property, then competition, individualism, and finally warfare.

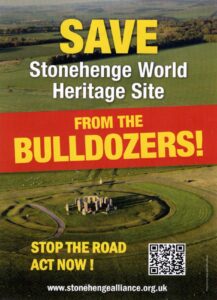

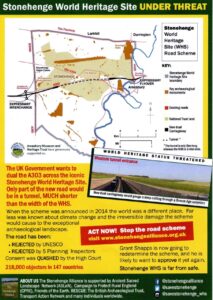

But there were also protests. Shockingly there is a plan to build a road under Stonehenge

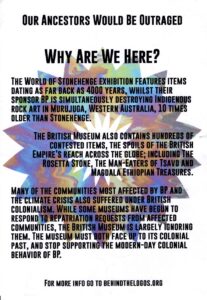

As well as BP sponsorship of the exhibition and the British Museum in general On the right it describes how BP while sponsoring this exhibition is simultaneously destroying indigenous Rock Art in Murujuga Western Australia 10 times older than Stonehenge

and much more: the issue of repatriation and the effects of the cllimate crisis on communities most affected by BP

The image behind the text is a reworking of BPs sunny greenwashing logo which is why this group is called behindthelogos.org

Just in case that isn’t enough bad news about BP, I read today on the site “We Don’t Have Time” a post that said

“BP to ramp up oil output, inaugurate U.S. Gulf platform in 2022 BP (NYSE:BP) expects to double crude oil production from its Thunder Horse project in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico and launch its latest production platform by the end of this year”

The company expects to produce ~200K boe/day by year-end 2022 from the current 100K boe/day at Thunder Horse, according to Starlee Sykes, BP’s Senior VP for the Gulf of Mexico and Canada.

BP (BP) also is preparing to start its fifth operated platform this year – Argos – the centerpiece of its $9B Mad Dog 2 project in the Gulf, but Sykes declined to specify in which quarter production would start.

“More Gulf of Mexico oil and gas helps improve emissions globally,” Sykes said, according to Reuters.

Last September, BP (BP) announced the start-up of Thunder Horse South’s phase 2 expansion and said a total of eight wells would be drilled to increase oil and gas production to ~400K boe/day by the mid-2020s.”

**************************************************

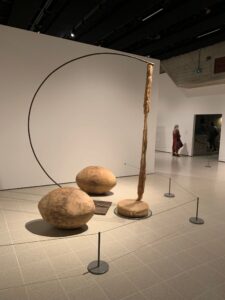

As Neolithic Art is an area far outside my expertise, it was fortuitous that as soon as I got back to Seattle, I went to a symposium about Nancy Holt’s Rock Rings 1977-78 at Western Washington University. ,

,

which draw on her exploration of Neolithic sites that she visited with Smithson in 1969 as well as her interest in celestial constellations and stone construction. They were completed after her more famous Sun Tunnels, and only four years after Smithson’s death. They align with Polaris the North Star. Her Sun Tunnels, 1973-76, like Stonehenge, align with the Summer Solstice.

Rock Rings is constructed of Triassic era Schist.

This entry was posted on May 7, 2022 and is filed under Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.

The Mad Hatter Hotel in London

For my first blog post on our exciting trip to London I feature our special hotel The Mad Hatter! As we checked in we were welcomed by Alice through the Looking Glass, literally. her hand enters a mirror which reflects the check in desk. Behind the desk was a large hat!

So why the Mad Hatter.? –

As this sign declares, “Southwark was the centrer of hat production for hundreds of years. Due to poor factory conditions hat makers were exposed to mercury in felt. Today we know that mercury poisoning causes dementia-lik symbtoms, but int he 19th century people assumed hat makers were all “mad” drunks, hence the phrase “mad as a hatter” which is wehre ourname comes from. This was famously satirzed by Lewis Carroll’s eccentric character The Mad Hatter. ”

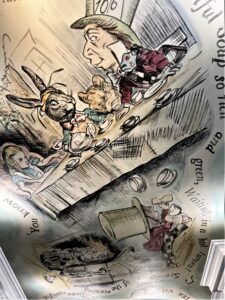

On the ceiling of the dining room we had the Mad Hatters Tea Party

On one window the mural blocked the view of the construction nearby

In the pub each booth had a different topic

Near the elevator, the descent to the rest rooms

In our bedroom we had some playing cards over the bed

View out the window. Insane development of high rises near by and in every direction

The Thames River Walk was only a block away

Our little hotel amid the development around it.

Alms Houses overshadowed by giant skyscrapers

Another view out our window in another direction

This small hotel is holding its own amidst so much development. Be sure to stay there if you go to London! It is super well located with a short walk along the Thames to the Tate Modern and the Haymarket, not tomention the National Theater where we saw the play “Small Island”

This entry was posted on May 4, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Our Blue Planet: Global Visions of Water

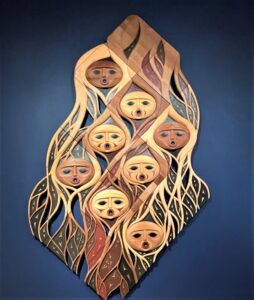

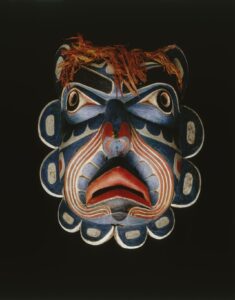

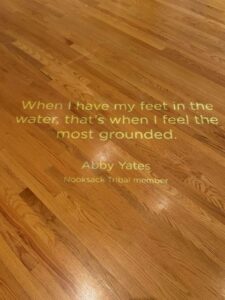

Canadian (Musqueam First Nation) Susan Point’s The First People suggests one theme of the amazing exhibition “Our Blue Planet:Global Visions of Water” at the Seattle Art Museum only until May 30.

Made of red and yellow cedar the piece seems to speak to us of both survival and sorrow, as these faces, each one distinctly different, call or perhaps sing to us with their rounded mouths as they float in interconnected streams.

The artist states:

“I am mostly inspired by nature and our connected human spirit. I try to illustrate our need to protect and restore our natural treasures and bring reflection and awareness to issues of concern in all our lives.”

“Our Blue Planet: Global Visions of Water” suggests that as it encompasses 92 works of art from 17 countries and seven native tribes.

During the pandemic three curators at the Seattle Art Museum assembled “Our Blue Planet: Global Visions of Water” with 74 artists from 17 countries and seven Native American tribes. It draws entirely from the museum’s permanent collection and loans from local collectors.

The curators, Pamela McClusky, Curator of African and Oceanic Art, Barbara Brotherton, Curator of Native American Art, and Natalia Di Pietrantonio, newly appointed Assistant Curator of South Asian Art, created ten themes that refer to water as necessary to life, as pleasure, as law, as mythic and as desecrated. They encompass celebration, poetry, ritual and catastrophe.

We are greeted at the entrance with a video of Ken Workman, a direct descendant of Chief Seattle, welcoming us, in the Lushootseed language.

It is moving and appropriate that he is standing on the shores of the Duwamish River as he greets us, the river of plenty before white colonizers arrived, and now a Superfund site and industrial wasteland.

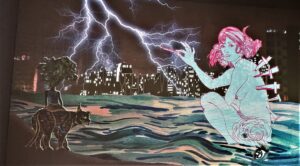

Immediately after Workman’s greeting we look up to see Carolina Caycedo’s fifty-foot banner that charts the change in a river from healthy to polluted, signaling the theme of the exhibition in one dramatic statement. Caycedo considers rivers as living and spiritual.

Caycedo’s video “A Gente Rio: We River” 2016 brings us the voices of the people living on the Paranà River as they explain their traditional ways as well as the devastating impact of the Itaipu Dam on the border of Brazil and Paraguay, completed in 1984. But these people have also protested. They know exactly why the dam was built: the result of corporate impunity.

Nearby is a hammerhead shark, hung at our eye level so we can look right into the eyes of its hammer shaped head. The Ghost Net Collective on the Erub islands (Northeast of Australia) call attention to the lethal presence of the nets with these sculptures.

Here are the ten themes of the exhibition.

“Rains that Flood and Hypnotize”

“Rivers and Canoe Journeys That Sustain Life”

“Oceans with Bodies Like Our Own”

“Pools of Pleasure and Reverence”

“Patterns of Water”

“Future Waters Through the Eyes of Women and Children”

“Where Water is Law in Northern Australia”

“Sea Creatures that are Honored and Endangered”

“Tragic Memories of Global Trade”

“Mythic Vision form Water’s Creation to Regulation”

“Desecration of Our Troubled Waters.”

Speak them out loud and they form a poem to water and the ways it intersects our lives, present, past and future. I will touch on a few of them here.

“Rivers and Canoe Journeys That Sustain Life”

As we enter the next gallery, we are greeted by the regalia created by Danielle Morsette “Colors of the Salish Sea Ensemble” . It is to be worn for an honorary stop on a canoe journey.

Here in the Northwest we have joyfully welcomed the return of the canoe journey beginning in 1989 . Tribes travel the ancestral sea routes of their cultures to a host tribe. It has particularly revitalized the youth in many native cultures. Twice I have been lucky to be visiting a Native Community as it formally welcomed participants on the journey with music, dance, and shared food.

Three videos by Tracy Rector (Mixed race/Choctaw/Seminole) Managing Director of Storytelling, Nia Tero Foundation celebrate indigenous resilience and the beauty of the land, sea and sky, their music, their poetry, their regalia. The artist states:

“80% of all biodiversity is on Indigenous-held territories. The world is healthiest where Indigenous People are actively living, thriving and being ‘in community.’ This [stewardship] is essential in saving the health of our planet.”

“Rains that Flood and Hypnotize”

Rain is both a blessing and a threat. It sustains us and our food, but it can overwhelm us as we have seen increasingly often. In this section the images include a compelling photograph by Raghubir Singh of four women huddled together in a monsoon downpour, that particular type of rain in India that is welcomed, but also frightening. We see an image of flooded fields nearby by Raghu Rai After flash floods near Jaipur, as the label states “The water rapidly gathers in shapes like lightning across the ground and around stunted trees, devastating the environment.”

But another work from South Asia in the indigenous Mithila style by artist Amrita Das depicts the dramatic effects of the 2004 tsunami in Sri Lanka as people’s villages are wiped out entirely ( For a literary description of this same tsunami read Amitav Ghosh, “A Town by the Sea” in Incendiary Circumstances, 2006)

Patterns of Water

Claude Zervos gives us the Nooksack River in cathode ray tubes, suggesting its underground networks. Zervas has spent years next to this river and watched it degrade as it was dammed.

“Waves” by Ogata Korin a large Japanese screen evokes the rolling sea

“The Roar of the Sea” by Suzuki Masaya suggests the sound of the sea through an intense process of laquering mother of pearl.

“Oceans with Bodies Like Our Own”

Seeing global nomad artist Paulo Nazareth’s lying on a beach suggests the peace that we all experience, lulled by the sound of the sea. But he is only briefly resting on his year long journey walking barefoot from Brazil to New York.

“Pools of Pleasure and Reverence”

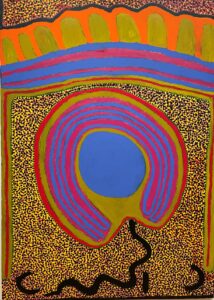

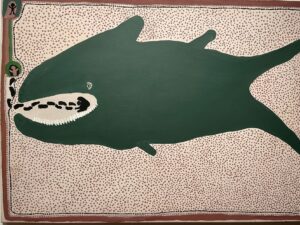

The dramatic image of Kurtal by Australian aboriginal artist Ngilpirr Spider Snell represents a spirit snake who “lives in a sacred waterhole called a jila. This desert spring is the only reliable source of water in all seasons . . . Kurtal is the moral protector of the right to use it and the land around it. …”

For a visit to Kurtal with Spider Snell, watch a trailer of Putuparri and the Rainmakers, by Nicole Ma

“Future Waters Through the Eyes of Women and Children” has some of the most provocative imagery in the exhibition. Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s video imagines a future world in which children collect the detritus of what we have left behind and create rituals with them. Here a child speaks to a head which becomes human, then a head again, and she takes it into the sea and burns it.

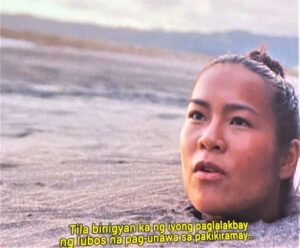

Also in this segment a still and a film by Ethiopian Aïda Muluneh, reenacts the process of getting water for survival in Dallol, northern Ethiopia, one of the hottest and driest places on Earth. Here is a view of it

As Muluneh explained:

“While travelling across Ethiopia for my work, I often encounter streams of women traveling on foot and carrying heavy burdens of water . . . women spend a great deal of time fetching water for the household.”

“Where Water is Law in Northern Australia” highlights four works on found aluminum by well known aboriginal artists, a dramatic departure from traditional eucalyptus, only seen here. The abstract patterns refer to law, ritual, ancestral power, clan designs, and, of course, the patterns of water.

“You are paper. We are sacred design. You make paper. Your wisdom is paper. Our intellect is sacred design, homeland, and ancestral knowledge of ancient origin. By painting these designs, we are telling you a story. From time immemorial we have painted just like you use a pencil to write with.” —Dula, Nurruwuthun (1936–2001), traditional leader of northeast Arnhem Land, 1999

Here you see Garrapara2018 by Gunybi Ganambarr,

Australian Aboriginal, Ngaymil clan, Northeast Arnhem Land. Ganambarr began painting after being told by an elder, “This is my wisdom. I’ll hand it over to you. Take it! Sit with us and live this life.” He says, “Soon I was learning the Yolngu side of deep significance… the foundations of the deep identity of the world.” The wavy designs refer to a specific bay and speak of clan affiliations.

Learn more here

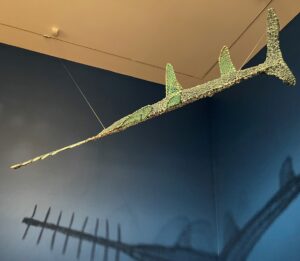

“Sea Creatures that are Honored and Endangered” The Mask of Ḱumugwe’(Chief of the Sea) from the Kwakwaka’waka rules over the water and this section that includes a sea turtle, a hammerhead shark (seen in the opening gallery), a sea bear and a sawfish. Both the shark and the saw fish are created in three dimensions from the fishing nets that are choking the sea.

Nearby is a bronze turtle called Dadu Minaral (turtle), 2007 by Dennis Nona from the Torres Straits (48000 kilometers, 1200 coral reefs at the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef, off the coast of Australia). Here the artist represents an historic initiation rite, by impaling the turtle on poles, but today the Torres Straits indigenous peoples are pioneering ecological partnerships to preserve this huge marine ecosystem.

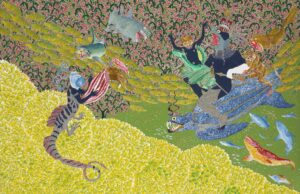

I love this image of the whale fish vomiting Jonah by Jarinyanu David Downs

And here is the sawfish by Syd Bruce Short Joe . It is also endangered

The highlight of “Tragic Memories of Global Trade” is the reinstallation of Marita Dingus’s intense homage to the slave trade- 200 Women of Afrrican Descent and 400 Men of African Descent. The artist created each headless body over year and a half as a meditation on the atrocities of slavery. The work as been reinstalled to correspond to the diagram of The Brooks, a slave ship on the late 18th century.

Not far away is an installation by Claire Pardington of two elegant 18th century figures drinking tea surrounded by slaves and sailors. She suggests the different status with two techniques, Limoges and porcelain, as well as the cost in human lives for the tea trade and the thirst for Chinese ceramics.

“Mythic Vision from Water’s Creation to Regulation” features Raqib Shaw’s The Garden of Earthly Delights V” showing an underwater world that is both beautiful and frightening in its fantasy and riff on Bosch’s famous painting. According to the curator “Beneath Shaw’s kitsch aesthetic lies his personal sorrow and his memories of fleeing Kashmir with his family. His idea of paradise is thus grounded in the physical and real space of Kashmir.”

“Desecration of Our Troubled Waters”

Among these works is a photograph by La Toya Ruby Frazier of the horribly polluted Braddock, Pa. where she grew up. Her Ted Talk talks about her work in Flint Michigan.

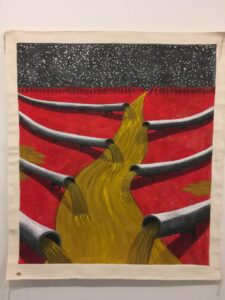

John Feodorov’s dramatic painting Desecration no. 2, represents pipe lines spilling pollution on native lands. Master Weaver Tyra Preston created special plain white Navaho rugs for the artist on which he painted, with some trepidation given the rugs’ powerful importance as metaphor of land and culture.

The exhibition includes so many more works that we see with new eyes from various parts of the museum. The rethinking of the idea of an exhibition brings together different cultural expressions to demonstrate that water is our shared concern, and necessary to our shared survival. In that way, the Indigenous voices are the most resonant in their respectful and deep understanding. But seeing their work and their voices placed among so many other cultures demonstrates the interconnectedness of everyone on the planet.

Finally, the curators reach out to our community:

“Our Blue Planet” is truly a groundbreaking exhibition.

This entry was posted on April 7, 2022 and is filed under Uncategorized.

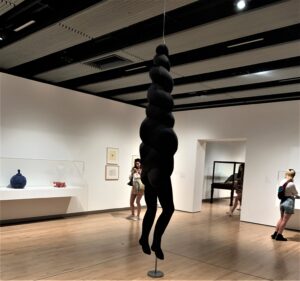

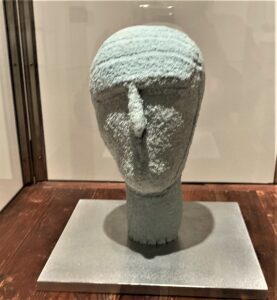

Embodied Change: South Asian Art Across Time at the Asian Art Museum

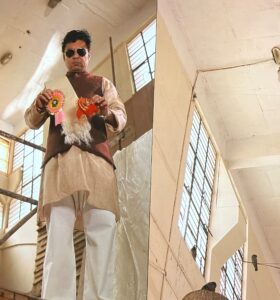

Natalia Di Pietranto, the new Assistant Curator of South Asian Art at the Seattle Art Museum explains her first exhibition “Embodied Change, Asian Art Across Time” as follows

“I wanted to . . . explore how the body is a site of both personal intimacy and possibility for change. . . I hope that visitors come away with a sense of how these artists are boldly imagining personal, political, and social change.”

The selection of artists covers a vast time span from the Indus Valley/Harappan era ( 3rd century BCE to 2nd Century CE) to the present moment. And in the first gallery, we see that time frame immediately, juxtaposed by the artist Chitra Ganesh, who selected early female goddess figures to be shown with her 2022 video Before the War. She is celebrating the transformation of historical goddesses into contemporary questing women in her video

(see top of post and below), drawn from comic books she read as a child on Hinduism.

In the next gallery, a startling series of works includes Humaira Abid’s wonderful carved wood sculpture with a political punch. Here you see a suitcase made of wood with two shirts, a skull cap and prayer beads, as for a religious traveler. Beside it is a gun. The piece is called Sacred Games. The gun sits there silently, unrelated to the peaceful suitcase and yet awaiting our own interpretations and anxieties.

In this gallery are F.N. Souza’s Self Portraits and Adeela Suleiman’s amusing helmet that includes a tiffin (lunch) box.

The Pakistani artist Nazia Khan has a Cage-corset, 2007 corset as well as photos of a performance in which she wears various corset like garments.

y

y

I loved the video by Bani Abidi Death at a Thirty Degree Angle. It gives us the art studio of a long time maker of commemorative statues, here filled with various stages of creation. In struts a local politician ready for his statue. As he poses with arms thrust up ( and talks on his cell phone at the same time), a local artisan sketches his outline, and other workers are creating other sculptures. Here we see the politician trying out various badges for his outfit. The artist uses split screens to enhance the off balance and humor as well as the skill of the artist himself.

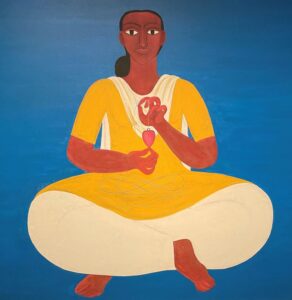

In the third gallery of the exhibition are familiar contemporary artists such as Rekha Rodwittiya

N. Pushpamala’s Motherland – The Festive Tableau, from the

Mother India project, 2009. Both Rekha and N. Pushpamela are redefining the historic goddess into contemporary women. In the case of Rekha she gives us an ordinary woman sitting with a powerful presence. In the case of Pushpamela she sends up the kitsch images of Mother goddesses in a hilarious historical recreation.

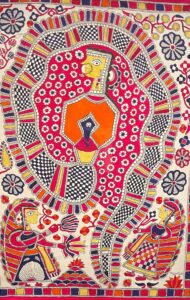

Mithila images by Jagadamba Devi of the the serpent goddess Naga Kanya suggest an entirely different perspective, more traditional as she is surrounded by her long serpent tail, but also very much in her own environment.

The quintessentially Indian Goddesses win out in the end with this gallery that spans tiny historical miniatures of dramatic scenes in which Durga takes on warriors and wins ( which were not allowed to be photographed). The contemporary artists images descend directly from those goddesses.

Outside the exhibition a scary neon Kali by Chila Kumari

Burman on the wall glows brightly

But the curator chose this image by Mithu Sen Miss Macho (Self Portrait), 2007 as the representative work for the exhibition.

Clearly a contemporary image of a trans woman, who looks out at us with her bold and beautiful eyes. By choosing this work the curator tells us that all that is new is old, and all that is old is still current in South Asian art. The concept of embodiment, of fluid gender, of powerful women has been around for a long time there, as well as all the social constructs that contradict that fluidity. While women in India may cover their heads with saris, they are some of the most powerful women I know. They still have Kali and Durga running in their veins.

Asian Art Museum open 10-5 Fri – Sun

This entry was posted on March 26, 2022 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Feminism, Uncategorized.