Michelle Kumata

this article originally appeared in a shorter version here

http://www.artaccess.com/articles/12634620

Bonfire Gallery “Michelle Kumata: Regeneration” to March 26

We are compelled to enter “Regeneration,” Michelle Kumata’s exhibition at the Bonfire Gallery by the banners in the gallery windows.

In the exhibition, Kumata is addressing the difficult subject of the long term legacies of the illegal incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

On the left of the entrance hangs “American Tragedy”, two banners depicting barely referenced facial features against a vague gray background behind real barbed wire. One has the face split between two banners, much as the experience of incarceration split the lives of those who were sent to those remote camps for up to four years.

On the left of the entrance hangs “American Tragedy”, two banners depicting barely referenced facial features against a vague gray background behind real barbed wire. One has the face split between two banners, much as the experience of incarceration split the lives of those who were sent to those remote camps for up to four years.

In the facing window, the banner “Shine” in brilliant color, suggests flying through the air, the Regeneration of the title of the exhibition.

Also in the window paper butterflies, made by a young Gosei (fifth generation) artist flutter toward the ceiling.

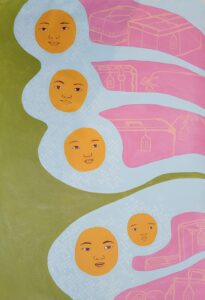

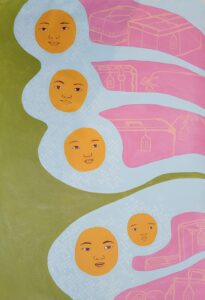

Inside the gallery “Butterfly Sun,” features a face that rises up

between butterfly wings.

Nearby “what We Carry” also soars toward healing.

You can just see their luggage outlined in the wings.

As we watch the Ukrainians leaving their country with a single bag, it reminds us that they are being as brutally uprooted as the Japanese in 1942.

Michelle Kumata a three and a half generation Japanese American artist, explores the long term effects for her parents, the Sansei generation, who were born in incarceration during World War II as a result of Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. This generation is the last to have a direct connection to this abrupt violation of human rights.

It is a cautionary tale that refers directly to contemporary racism, forced exodus, and migration because of climate change.

“Regeneration” poignantly explores the ways in which incarceration survives into daily lives: the Japanese American community continues to be affected by the conditions that led to the incarceration.

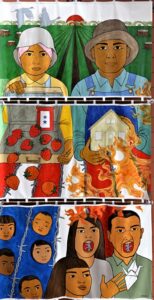

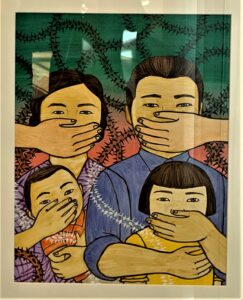

Michelle Kumata offers a multimedia approach to recovering memory and experiencing loss after decades of suppression. The largest expression of that, at the back of the gallery, is the lower section of the artist’s trademark work “Song for Generations.”

The entire banner represents a dignified husband and wife at the top, with their lush fields behind them, cleared from forest; in the next panel, strawberries fall to the ground and a house is burning. The bottom section, in the Bonfire exhibition, dramatically represents the ongoing pain of the incarceration with barbed wire in the open mouths of two Nikkei and flames around their heads. The strawberries become children, those born in the camps amidst barbed wire, but at the very bottom, a girl lets fly away a paper crane. You can see the whole mural in a small print nearby.

The next section of the exhibition features photographs of the artist’s maternal and paternal grandparents that document their lives before, during and after incarceration. The artist’s mother and father were born in the camps. These touching images speak to the real family stories of immigrants who had businesses and lives destroyed in 1942.

Gibson Garu

Koinobori

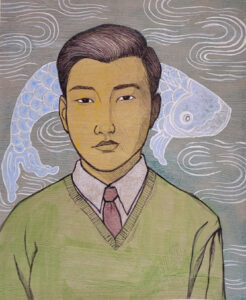

A similar feeling comes from paintings based on formally posed portrait photographs from the Takano Studio Collection from the late 1930s to early 1940s, called here “Nihonmachi portraits”

( Nihonmachi is the name of the Japanese business area of the International District before the incarceration.) The artist recreates a selection of these dignified portraits as paintings, again referring to lives before the camps.

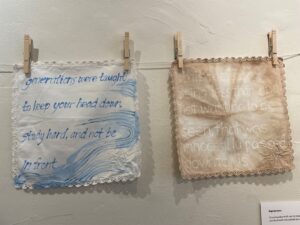

Facing these is a creative expression of memory: handkerchiefs with inscriptions such as “Generations were taught to keep your head down, study hard, and not be in front.”

Nearby are “furoshiki” traditional Japanese wrappings for packages, here holding unspoken memories. Over generations as the artist states “the knots slowly loosen, releasing the pain, shame and anger. And we allow ourselves room to carve and define our own unique identities, to transform and fly.”

Resilience A Portrait of the Artists Maternal Grandparents

Be Quiet the alienation and oppression of Japanese Brazilians during World War II

In addition to all of these thoughtful approaches, a slide show of photographs alternates with quotes from a broad selection of members of our contemporary Japanese American community. The destruction of the heart of the Japanese community, Nihonmachi, and the unwillingness of survivors to speak of it are two major themes.

Bellevue Art Museum “Emerging Radiance, Honoring the Nikkei Farmers of Bellevue” to March 13

Michelle Kumata has a second major installation at the Bellevue Museum of Art “Emerging Radiance, Honoring the Nikkei Farmers of Bellevue.”

It features an immersive mural that uses augmented reality that enables us to actually hear three Nissei farmers of Bellevue tell their stories. The stories are based on interviews recorded in the Densho Digital Archive an incredible online resource that expands our understanding of the lives of those who were incarcerated.

YOu can hear the testimonies on her website

Michelle Kumata boldly experiments with representing the ongoing psychological damage of the original historical event of Japanese incarceration. She creatively makes audible what has been unspoken and makes visible what has been buried.

This entry was posted on March 8, 2022 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Art in War, Contemporary Asian American Art, Uncategorized.

Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist

“Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist, An Issei Artist’s Journey” (Cascadia Art Museum, Edmonds, to February 20)

“Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist, An Issei Artist’s Journey” (Cascadia Art Museum, Edmonds, to February 20)

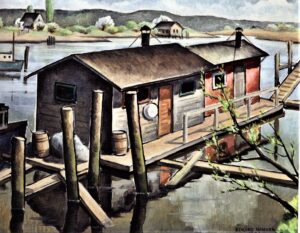

Kenjiro Nomura (1896 – 1956) came from Japan to Tacoma at the age of ten in 1907. while living in Tacoma as a child, he attended a Japanese Language school where he was fortunate to have a skilled teacher who taught him “graphic skill and developing aesthetic sensibility that served him well in adulthood.” ( Barbara Johns Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist p 14)

When he was barely seventeen his parents returned to Japan leaving him to fend for himself. He managed to not only survive but to find art training and then to be recognized as an artist. He moved to Seattle from Tacoma when he was 19 and began to study art with Fokko Tadama who had recently relocated from New York City bringing East Coast styles with him.

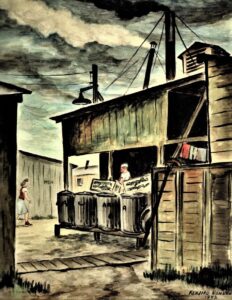

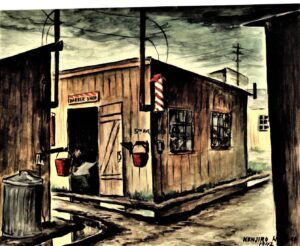

Nomura supported himself with his own sign painting business in the Nihonmachi, the heart of the Japanese immigrant community. As discussed in Barbara Johns excellent book of the same title as the exhibition, Nihonmachi provided a rich cultural environment.

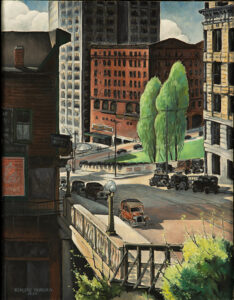

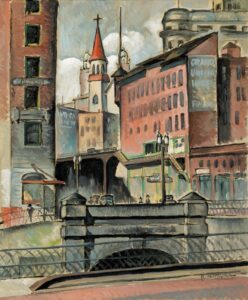

Nomura made a major contribution to American scene painting with his 1930s urban street scenes. He carefully observed complex intersections in such familiar locations as 4th and Yesler.

By the end of the decade Nomura was acknowledged as a major artist. His original take on the idea of American scene with its complex composition and spatial relationships makes his work distinct and in some ways more sophisticated than his contemporaries like Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. Although here we see no obvious reference to his Japanese heritage, early training in Japanese painting affected his way of seeing in subtle ways.

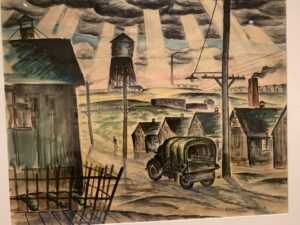

But suddenly it came to an end when on February 19, 1942, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the infamous executive order 9066 authorizing the relocation of all persons considered a threat to national defense from the west coast of the United States inland.

The order fell like an ax on the lives of people of Japanese descent regardless of whether or not they were citizens.

This February is the 80th anniversary of that order.

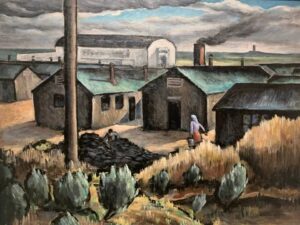

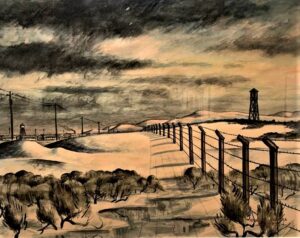

Nomura and his family were forcibly incarcerated along with 120,000 other people of Japanese ancestry. They first went to the State Fair Grounds in Puyallup,

then to Minidoka, in desolate Hunt, Idaho.

But Nomura never stopped painting! He made over 100 watercolors of the buildings, the people, and the natural environment in the camps. They remained rolled up in a closet until the 1990s.

Nomura’s son, George, brought work out of storage about 1990. It was shown at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle in 1991 and toured for twenty years. Curator David Martin carefully chose twenty of them for this exhibition and orchestrated their donation to the Tacoma Art Museum.

After years of internment, Nomura returned to Seattle. He then confronted severe personal challenges, most tragic of which was his wife committing suicide.

But with the encouragement of friends and probably also his second wife, he began painting again His work transformed completely, perhaps not surprisingly after so many traumas, into dynamic abstractions that he created up until his early death in 1956.In this too, he demonstrated a completely original approach.

Folk Dance 1950 collection of Michael and Danielle Mroczek

Shopping Center 1950 Collection of Lindsey and Carolyn Echelbarger, promised gift to Cascadia Art Museum

All images from the incarceration on in the collection of the Tacoma Art Museum.

This entry was posted on February 1, 2022 and is filed under American Art, art criticism, Uncategorized.

Christina Reed: Confronting Whiteness and its Exclusions

photograph by Henry Matthews

Christina Reed’s exhibition “Reckoning” confronts us with our own whiteness and oblivous racism head on and with ingenuity.

The exhibition consists of three parts. The first is Reflection, a wall filled with large black and white prints based on historical photographs of white people: juries, business men, families, picket fences, interspersed with the words of the declaration of independence, maps of redlining.

The white people are passive, but collectively they create a wall of oblivious privilege. Interspersed with the images are repeated quotes from the declaration of independence underscoring the racism of the white founders as they wrote of equality even as slavery was perpetuated and black people denied all rights.

Inserted every few feet is a mirror. We can see our own white faces as part of the white racist gaze, or for a visitor of color, surrounded by this wall of privileged exclusion.

We turn from this immersion in whiteness to the second part of the installation, Regard: White Gaze. Thick glass squares hanging from the ceiling painted with blue eyes that gaze directly at us. A literal white gaze, the glass feels claustrophobic as we observe it more closely, suggesting the feeling of being watched, judged, monitored, and even threatened simply by the act of looking. It is very difficult to walk through this intense forest of glass panes, another wall of privilege, so we walk around it.

Photograph by Susan Fried

photograph by Henry Matthews

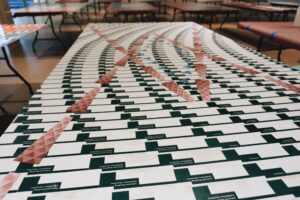

The third part of the installation Repair suggests actions to counter racism. There is going to be a closing on February 17 5-7 pm(hopefully) in which people wear signs that have references to various aspects of ways to counter racism. On one side of the sign is an oblique reference. You have to turn the sign over in order to know what it means. In other words you have to do more than look at the sign.

Then once you turn it over a wide range of possible ways forward are offered some educational, some personal, some joining with others. They include references to the 1619 project, a history of slavery and the roots of racism. Another explains red lining, a third “12 out of 18” lists the 12 Presidents out of the first 18 who owned slaves. Other actions suggest observing microaggressions, euphemisms. And of course speaking to our elected representatives about racism is one of the suggestions and supporting diverse cultural organizations. Revolution is not included but volunteering on projects related to the Criminal Justice System is one of the more specific community actions.

The Rosetta Hunter Art Gallery Seattle Central College 1701 Broadway, 2BE2116 Seattle, WA 98122

206.934.4379 Hours10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. Monday through Thursday Admission is free. They have briefly closed because of COVID concerns but new dates are February 8 – March 24

Christina Reed received support for this project and did much of her research at the historic home and library of the James and Janie Washington Cultural Center 1816 26th ave in the Central District. If you want to know more about this important artist, come to the unveiling of a bronze statue of Dr. James W. Washington and the restored “Fountain of Triumph” Washington’s last public monument. The “Fountain,” formerly located on 23rd ave, addresses salmon migration as a metaphor of the difficulties of survival for African Americans. The Event will be at 24th and Union part of the newly built Midtown Center, February 26, 2022, 6:30pm to 8:30pm. Call the Washington Foundation for Information 206-709-4241.

This entry was posted on January 31, 2022 and is filed under Racism, Uncategorized.

Two Murals in Women’s Prisons: Lucienne Bloch and Faith Ringgold

This is a detail of the center of Lucienne Bloch’s mural

“Cycle of a Woman’s Life” sponsored by the WPA in the mid 1930s. Above are photographs of Bloch painting the mural.

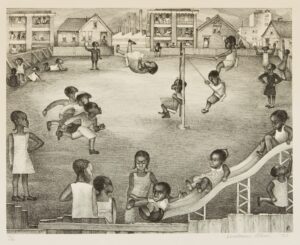

Here is Faith Ringgold’s mural “For the Woman’s House,” also painted in a woman’s prison, in 1972. It was her first public art commission.

Both artists consulted inmates about the content of the mural.

Bloch’s mural showed an ideal life of children playing happily together in a playground.

Ringgold shows careers that the women thought were “outside their reach” as the NYTimes article puts it. Not sure if that is accurate, why not careers they might want to aspire to have when they got out of prison.

Both artists wanted to alleviate the dreadful environment in which the inmates found themselves.

Bloch’s mural was covered up almost immediately, the claim of the administrators was that it gave the inmates false hope. when the prison was demolished, it disappeared forever.

Ringgold’s mural at Rikers has been moved several times. It is currently being moved to the Brooklyn Museum.

Art Historian Michele Bogart stated ” I keep wondering if they are doing a disservice to the people who are still at Rikers.”

Both of these artists believe that art can make a difference.

Bloch worked with Rivera on his mural at Rockefeller Center before it was demolished.

Ringgold has spent her whole life engaging in art with social content. Early in her career she created work on fabric she could roll up and bring with her to save the cost of shipping,so, she said she could collect that money as an honorarium.I remember hearing her speak about this in Austin Texas in 1978.

Bloch worked for the WPA during the 1930s, then spent her whole life making murals and teaching workshops on mural making. I was fortunate to attend one of those late in her life in El Paso, Texas, as well as to go to a one person show she had in California. Here is Bloch with her lifelong love and partner in art Stephen Dimitroff in El Paso.

The real tragedy of this story is the prison itself. The prison where Bloch worked was intended to be an ideal new prison, but it deteriorated into a dreadful place and was demolished in the 1970s

Ringgold’s mural was moved several times, after it was threatened, then it was also covered up.

We all know how ghastly Rikers is as a prison.

Where can art fit in these places? I know of artists who do art in prisons with the prisoners, art and poetry, and drama, and other creative activities. this may be more productive than painting something on a wall, but the dreariness of these places is hard to fathom.

There are no easy answers. But I respect both Bloch and Ringgold as well as the government entities that sponsored them, for trying to add something positive to a dreadful place.

This entry was posted on January 20, 2022 and is filed under Art and Politics Now.

Carrie Mae Weems The Shape of Things

Carrie Mae Weems the Shape of Things

included 7 parts!

It was in fact partially a retrospective

The first installation at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City is a set of megaphones in the large space. this called “Seat or Stand and Speak” was an opportunity to sound off or not, as we began to think about our current times. Mostly people did not sound off.

Photo Credit: Stephanie Berger

The next stop was inside the blue cyclorama you see in the background: called Conditions, A Video in 7 parts with original music by Jawwaad Taylor.

This image of performer and choreographer Okwui Okpokwasili sitting in a chair with papers falling like leaves around her begin the video. As Aruna D’Souza wrote in the New York Times: “Weems’s voice, with its deep, round tones, tells us that to navigate the now, “she needs to look back over the landscape of memory.”

Weems stated in the press release:

“I am fascinated by 19th century media, so for the Drill Hall I created a cyclorama that contains a new film that pits the rise of the right along with its puppeteers, clowns, jokers and two-faced speakers & spies, charlatans & prophets of fake news, conspiracy theorists against the emerging forces of progress. In this world, ‘normal’ is turned on its head and all bets are off.

“It is a time of murder, mayhem and mass protest and when covert operators of corruption bear their heads for all to see. My work centers on what happens when all facades are stripped away, and the people are left standing face to face with the realities of our time.”

The artist also narrates the film which is 40 minutes long. As Marley Marius put it in Vogue: ( I didn’t find this information anywhere)

“Weems mostly narrates these vignettes, employing her richly resonant speaking voice to discuss, among other things, the ubiquity of police brutality (“Imagine the impossible. Imagine the worst of the worst. And know that it is always happening”).”

Here is one still from the film of a black man walking, probably referring to the recent murder of Ahmaud Arbery, but it could be any black man. The recording of the woman who called the police in Central Park against a black man birding can be heard in the background of the two women seated in silhouette at the top of the post and here

Shadow puppets of slave owning women.

Another theme was migration, both in boats and on land.

and the border fence on our Southern border.

But there were images from the treacherous crossing of the Mediterranean. You can see it is footage from the news. In front is one of the seats where we watched the film, keeping in mind that we were completely surrounded by the images as in the 19th century Cyclorama.

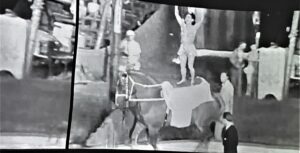

The video also included some historic images of circus performers and a clown ( evidently referring to T, keeping in mind that clowns are smart people who pretend to be someone they are not)

The clown is blurry, but he was moving a lot, and it seems appropriate somehow that he is hard to see.

The January 6 riot was also included and below a reference to white racists from the earlier Civil Rights era or before.

There were people silently marching, with no signs. I wondered if they represent BLM marchers, although we all had signs, or is it a staged march representing protests against injustice everywhere. The artist photographed them in summer 2020

There was a lengthy segment of various people standing in the rain I don’t know what they mean. Suggestions welcome. It has the title Conditions

As well as numerous silhouettes of people marching

Finally I give you this repeated image of three women holding up globes.

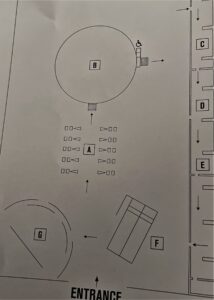

There were three more segments to the exhibition. Here is a diagram of the whole piece to orient you. I have so far mentioned A and B

A long corridor (on right of diagram ) started with

C “Its Over – A Diorama, with memorials honoring some of those who have died. The theme of the globe reappears

A segment from earlier works

B Missing Links from 2004 various animals such as zebra, elephant sheep and wolf, dressed up in fancy clothes, In the brochure an earlier version is called The Louisiana Project 2003

and E The Weight 2021, more globe/balloons on African heads.

OK that’s three segments.

There are two more!

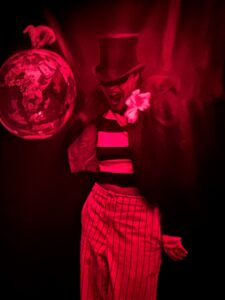

F was like a cabaret in a darkened room called Lincoln, Lonnie and Me 2014, it included the Gettysburg Address, in what the press release calls a Pepper’s ghost illusion with music by Jason Moran,

I like that my image looks like a ghost! Lonnie is Lonnie Graham an artist and activist.

This second image is from the press photos

Photo Credit: Stephanie Berger

Nearby in the darkened room were carnival promoters, another globe

and finally

G All blue, A Contemplative Site 2021

It was an old door at the top of some steps with a full moon. Here it is

and with me

I am trying to assimilate this incredible multipart installation. It is meditative, angry, hopeful, historical, contemporary, a compendium of images that together speak to our moment, our fragile moment in history. I am glad that Carrie Mae Weems seems to see the forces for good as stronger than those for evil. Or do we see a Civil War here that is still being fought?

In these dark days coming up to the anniversary of the attack on the Capitol, it is hard to believe in that, but if we all stay actively resisting evil in what ever small or large way that we can it will make a difference. Weems leaves us to figure that out for ourselves.

This entry was posted on January 5, 2022 and is filed under African American history, Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, Uncategorized.

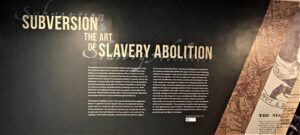

Subversion: The Art of Slavery Abolitionism

We saw this provocative exhibition “Subversion and the Art of Slavery Abolition,” at the Schomburg Library for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, when we stayed there last week.

Curated by Dr. Michelle Commander, Associate Director and Curator of the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery, it is an astonishing work of research in the New York Public Library archives.

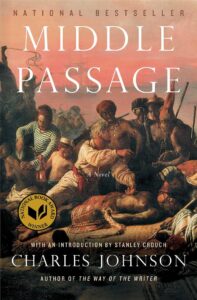

As it happens, I am immersed myself in the theme of black creativity in the US as I am reading Charles Johnson’s astonishing book

The Middle Passage, which, it seems to me, is a type of partner to Moby Dick. Johnson details the realities of a slave ship in horrifying detail with a narrator, Rutherford Calhoun, who tells all. Moby Dick of course was focused on the horrors of the whaling industry and only mentions passing slave ships in the sea. all narrated by

Ismael, a sole suvivor of the disaster.

At the same time, I am also reading a novel by Walter Moseley, brilliant writer of “gum shoe” detective stories that are much more a commentary on black life in America ( in this case 1970s ). His descriptions of many many skin colors alone is worth reading, but of course, the pervasive violence against blacks by the police is a dominating theme. Easy Rawlins is the hero, outsider, renegade private detective survivor in 12 novels by Moseley over thirty years.

On this same trip to New York City we also saw Carrie Mae Weems exhibition, about which I will write separately, as well as a contemporary artist, Leonardo Bezant

at the Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem.

at the Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem.

“Reliquary For The Black Boy Who Sits At The Window Dreaming(A Collection Of Conjurings and Letters)”

incredibly intricate work with beads with several metaphorical layers.

In addition I am reading “The Matter of Black Lives” compiled by Jelani Cobb and David Remnick , New Yorker articles over decades on Black life in America.

So this exhibition at the Schomburg was extremely timely for me to see. All of the works are in the public domain on the website for the NYPL. The credit for all of them includes Photographs and Prints Division. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden, but I will only include the collection in the caption, which is an intriguing study in itself.

I am simply quoting from Dr. Commander in the text of this post. I am not able to rephrase or paraphrase her ideas. That means it is a bit long, and wordy, but worth reading. Also worth going to the website where every single one of the art works are reproduced.

(there is also an audio tour of the exhibition on the website that goes into the imagery and the topics) :

Dr. Commander introduces the exhibition with the following statement

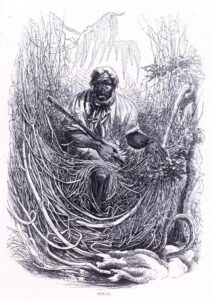

Osman the Maroon in the Swamp 1857 Slavery Collection

“Transatlantic slavery was devastatingly brutal in its utter disregard for human life. Across the Atlantic World, avaricious traders and enslavers ripped apart families and communities, callously murdering millions of people of African descent and legalizing the extraction of labor from the unwitting survivors. The United States was founded on the inalienable principles of equality, liberty, and democracy on the one hand, while the nation’s rise was enormously dependent on slavery speculation on the other. This inherent contradiction set the stage for centuries of political and philosophical conversations and unrest. While slaveholders and vigilantes threatened and attempted to control Black bodily autonomy, enslaved people and their allies artfully countered this malevolence via everyday and more formally coordinated types of resistance.

This exhibition highlights several of the ways that abolitionists engaged with the arts to agitate for enslaved people’s liberty in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Though the major focus is on American (U.S.) and British efforts, abolitionism was transnational, dynamic, and controversial.

Anti-slavery advocates immersed themselves in letter, pamphlet, and speech writing campaigns and founded newspapers, despite known and unknown dangers. Visual artists created illustrations, paintings, and photographs that featured the mundane yet absolutely reprehensible aspects of slavery to alert everyday citizens to the institution’s many horrors.

Novels, slave narratives, poetry, and music were also significant and often encoded with insurgent messages that inspired the establishment of anti-slavery societies and the formation of one of the movement’s most subversive projects: The Underground Railroad.

All of these strategies were profoundly necessary as activists rallied the public to agitate for the cause and urged governmental officials to abolish slavery. Abolitionist arts appealed to the public’s moral, religious, and political convictions, eventually yielding a robust stream of anti-slavery propaganda and radical acts that could not easily be ignored.

In 1791, the abolitionist William Wilberforce gave a speech before the British House of Commons, declaring that great responsibility came along with the awareness of slavery’s cruelty. He ended his speech with the declaration, “You may choose to look the other way but you can never again say that you did not know.” This sentiment no doubt energized and emboldened abolitionists’ incredible displays of bravery, intellect, craft, and artfulness in the fight to end slavery.”

She divided the exhibition into six themes

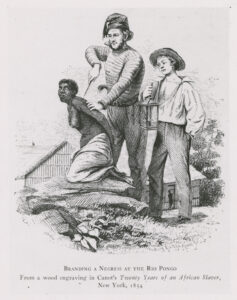

1 Brutality and Avarice

Slave Traders Branding an African Woman Creation: 1854 Slave Traders Branding an African Woman at the Rio Pongo (in Guinea, West Africa) Taken from “Captain Canot, Twenty Years of an African Slaver” Punishment and Torture Sub-Collection, Slavery Collection

“The items in this section have been selected to show the early roots of capitalist avarice/greed in the Atlantic World. The items not only highlight that slavery was seen as an everyday business in its accounting practices and uses of brutality to keep enslaved people in their places, but also gives a sense of the racist philosophies that maintained and even used the Bible to rationalize the “need” for the institution.”

2 Resistance and Rebellion

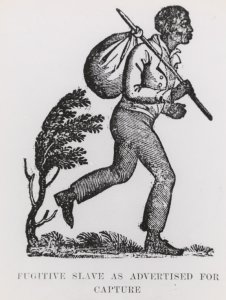

Fugitive Slave as Advertised for Capture 1857 Fugitive Slave as Advertised for Capture Fugitive Slaves Collection

“This exhibition begins with examples of enslaved people’s resistance and rebellion. Their actions– running away, fighting back on slave ships and in the Atlantic World, establishing maroon communities– most shocked and alerted the world to the injustices and inhumanity of the slave trade and slavery as it existed across the Atlantic World.

It should be noted that abolitionists argued mightily over the use of violence and force. Some felt that fighting back and being otherwise belligerent in everyday interactions would only support enslavers and other pro-slavery individuals’ arguments that slavery was beneficial because it tamed and educated so-called “primitive” people of African descent.

Smaller forms of resistance, too, were important as they kept enslavers on their toes and gave enslaved people some sense of power and control over their lives.”

3 Abolitionism

Sojourner Truth Photographer Unknown Circa 1860s

“Art denotes strategy, ingenuity, and imagination. Abolitionists of all stripes participated in the cause, prompted firstly by the refusal of African captives to abide slavery’s many violences. Enslaved people worked slowly, fought back, and set plantations aflame, giving pause to enslavers. They fellowshipped with one another and created kinship networks, despite all efforts to break their spirits and resolve to live and love. Self-liberated fugitives from slavery banded together as well as with freepersons to establish maroon, mocambo, and quilombo settlements in hills, valleys, swamps, and mountains. As instances of insurrection intensified on ships in the Middle Passage and across the Atlantic World, objections to the institution of slavery by social reformers and everyday citizens also increased, reaching fever pitch by a diversity of anti-slavery proponents in the nineteenth century.”

“Sojourner Truth (1797–1883) was born enslaved in Ulster County, New York. In 1826, she escaped the bonds of slavery with her infant daughter in tow and successfully sued to gain custody of her minor son. She later became an outspoken abolitionist and suffragist, giving the famous address known as the “Ain’t I a Woman” speech in 1851 before the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio.”

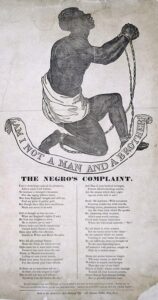

The Negros Complaint 1870 Slavery Collection

4 Poetics and Music

“Abolition-minded poetry and music got to the heart of the matter using few lyrics, generally. Poetry and musical lyrics were printed in collections as well as re-published as complements to essays and speeches in anti-slavery newspapers, almanacs, and children’s books. They were also printed and sold as broadsides at anti-slavery meetings and other events. The items in this section include those that take on the persona of enslaved individuals to address their inner turmoil and longings. Other pieces recount the everyday horrors with which the enslaved were forced to contend from the Middle Passage to the plantation.”

5 Narratives of Fugivity & Fidelity

“The items in this section include several fugitive slave narratives, anti-slavery fiction (Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin), and the ways that Black loyalty to the nation was encouraged and expressed through participation in the Civil War. Narratives of enslavement were important to the cause of abolitionism because they offered first-hand accounts of the many horrors of the institution. These narratives appealed to the sympathies of white Northern men and women, with the texts that were written by men very much reflecting on honor and manhood. Women’s narratives often delved into sentimentalism and the authors’ affective experiences as a mother and/or wife, which were feelings that women of the time, regardless of their backgrounds, might be emotionally moved by. These narratives also revealed a sense of enslaved communities’ cultures and beliefs, the restrictions that were placed upon enslaved people, the violence that undergirded slavery, as well as some of the artful ways that enslaved people resisted, banded together, and escaped their enslavement.”

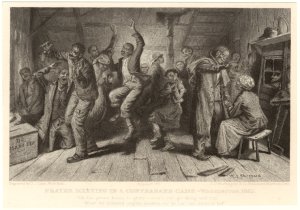

Prayer Meeting in a Contraband Camp 1887 Prayer Meeting in a Contraband Camp, Washington, 1862 William Ludwell Sheppard

“Encampments that were established near Union forces during the American Civil War by liberated enslaved people. This prayer meeting portrays its attendees worshipping charismatically. They are fellowshipping, singing, clapping, and dancing with one another perhaps in celebration or, at the very least, in hopes that liberation—worldly or heavenly—was truly to come”

6 Anti-Slavery Children’s Primers

“Abolitionists did not forget the very impressionable new generation. Within many larger publications (almanacs, newspapers, and other periodicals), there was a children’s section to help groom an abolitionist future. The Slave’s Friend is one example of a publication that was dedicated solely to children. Authors also wrote children’s books on slavery and various versions of the alphabet of slavery to appeal to children as well as to assist parents and other adults as they broached the difficult topic with youth. This section also includes an image of The New York African Free School, a critique of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s representations of Black children in her anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the Nautilus Life Insurance companies death ledger, containing the records of enslaved people.”

Eva and Topsy Creation: Circa 1860s Harriet Beecher Stowe Lithograph

“Eva and Topsy, major characters from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, are shown here in an affectionate pose. Throughout the novel, however, Topsy is portrayed most memorably as a naughty “pickaninny” who needs corrective whippings and consistent instruction to behave because she has no family and simply does not know better.

While some readers felt a moral dilemma about slavery as they read about Topsy’s behavioral struggles, others found that this storyline was evidence that slavery had a good overall effect on improving what they viewed as inherent Black pathology. Like many of Stowe’s other presumably well-intentioned, though exceedingly stereotypical characters, derogatory minstrel shows featured the Topsy character to poke fun at the intellect of Black people. As Stowe discovered from the backlash she received from abolitionists, literary and visual representations of Black people were and remain political.”

Each theme has detailed information sometimes tracts, sometimes books, photographs, prints. You can see them all on the website. Scroll down to the online gallery.

Seeing this exhibition at this time of so much new awareness of racism in the US both past and very much present gives us an appreciation of the huge power of resistance in creative expressions. Collectively these tracts, images, poems, songs, photographs, tell us the power of the human spirit to resist unspeakable brutality.

This entry was posted on January 2, 2022 and is filed under Abolitionism, Art and Politics Now, Uncategorized.

Morgan Peterson on Greed, Power, Control and Murder

“Born of our Culture: American Excess” a recent installation at Method Gallery by Morgan Peterson tells it like it is in our contemporary moment. Morgan Petersen has long been fascinated by true crime and the amplifying role that media plays in our culture starting with the 1969 Charles Manson murders

My fascination with true crime began as a small child reading about the Tate/Labianca murders committed by the Manson Family Cult late in the evening on August 8,1969. This installation mirrors events that transpired that evening which captured the attention of the world as they unfolded while revealing the driving forces of racial discrimination and profiling that repeat throughout history.

She interweaves references to media hyped events with her commentary on the American culture of Excess. It could not be more timely in the age of the insanely overpriced and climate destroying NFT and bitcoins.

The exhibition actually consists of three interrelated installations:

we first see a giant reflective glass surface with oversized components of drugs and their use referencing the opioid epidemic. A huge bottle of oxycontin makes it hard to miss the point. Here is

Once Upon A Crime, The American Epidemic

The epidemic is based in greed:

the installation specifically references Martin Shkreli on the credit card who raised the price of life saving drugs from 13. to 750. per pill.

Peterson also comments on excess more subtly in the pattern of the glass surface. It is based on the cover of an album which the artist describes as “the most expensive album ever sold, Once Upon A Time In Shaolin . . . This piece speaks of the overreaching power in politics, being born with a silver spoon in your mouth, the opioid epidemic and all over corruption.”

A second installation features Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton’s iconic Emmanuel chair.

It refers to Black Panther Fred Hampton’s horrific murder by police just after Charles Manson’s effort to link Black Panthers to multiple murders by his cult members in 1969 in order to start a race riot. The Charles Manson cult murders of Sharon Tate, Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, Steven Parent, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were followed shortly after by Fred Hampton’s assassination by the police, and twenty years later by Newton’s murder.

Newton and Hampton were both brilliant founders and spokespersons for the Black Panthers. Their programs such as “giving breakfast to children and creating alliances among street gangs, food banks, medical clinics, sickle cell anemia tests, prison busing for families of inmates, legal advice seminars, clothing banks, housing cooperatives, and their own ambulance service” were incredibly successful which is why the FBI decided they were terrorists. They were disrupting the capitalist machine and the racist oppressions that keep it running.

Morgan Peterson honors their deaths with this installation which includes specific vintage furniture and props from the 1960s that she carefully located. On the coffee table you see a book and matchbox precisely recreating the scene of the murder of Hampton. The stone sculptures of the Black Panthers suggest by their small scale, the oppression of our dominant gaze

A third installation refers to our very present moment

This carefully constructed wooden gallows with its lynch noose made of 11000 small pearls woven by the artist in a special Russian spiral stitch, speaks for itself. The horror of our January 6 attempted coup, as well as the role of greed in racism in our country is spelled out here.

( The artist bought the pearls with the stimulus check from the government during the pandemic. She made the work in collaboration with wood working master Alexander Pope.)

Peterson speaks to the current insanity of our country, the thirst for power at all costs.

Peterson was trained as a glass artist, and glass is prominent in several elements of the exhibition. But these glass works move way beyond any traditional idea of glass. The simplicity and familiarity of the material belies the complexity of the technique needed to create art with it and as a material that can speak to political issues.

Photo Credit Russell Johnson

Above the Emmanuel Chair are three glass engraved cameos, two are portraits of people murdered by Manson.

Morgan honors these people with so called cameo “mourning portraits.” The third cameo is a specific image of mourning, a quote from a sculpture of a veiled virgin.

Cameos are demanding to create: they are based on reductively carving away a glass layer to reveal what is underneath.

Paula Stokes, a founder of Method gallery, suggests in a fascinating interview with Peterson that carving away of the surface reveals imagery underneath that can become sinister.

One other group of works in the exhibitions using mirrors and various luxury accouterments refer to cocaine use by the wealthy.

The intertwining of the rich use of cocaine, the opioid epidemic, and the overpricing of life saving drugs, lead directly to the pearl encrusted noose held in the hands of those in power to entrap and destroy the powerless.

The Black Panthers were taking power from the ruling class and therefore had to be stopped. We can draw a straight line from them to the present moment.

Embedded in both history and the present moment, “Born of our Culture: American Excess” suggests the true state of our world, in the massive disparity between the practices of those who control power and will murder those who threaten it, and those who seek simply to survive day to day.

As Ann Applebaum wrote in a recent article in the Atlantic, “The Bad Guys are Winning,” the big shift is the level of impunity with which the wealthy now operate. Autocracy operates across national lines and with absolute disregard for the well being of individuals.

Also explaining the depth of our problem is Sarah Chayes book

On Corruption in America and What is At Stake.

Chayes speaks of the many headed Hydra of greed , when you cut off one head another grows, and she traces greed in her book all the way back with Midas. She and Applebaum both point to the intersections of autocracies and kleptocracies, as a network that ensures their own survival above all else.

Likewise Morgan Peterson addresses the hydra of greed is this compelling group of installations. But she connects the dots right to the racism that underlies greed, as well as its outcome in assassination and lynching.

This entry was posted on December 3, 2021 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.

Ghost of a Dream and Elizabeth ‘Mumbet’ Freeman

“Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told that I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it, just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman, I would.” Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman

Joana Vasconcelos, “Valkyrie Mumbet,” 2020, 384 x 672 x 504”,Stephen D. Paine Gallery all photos of Valkyrie by Will Howcroft. Courtesy MassArt

Ghost of a Dream, “Yesterday Is Here”, through December, 2021

Gudrun Arsaelsdorrit Edelsten and Lynn Puritz Warner Lobby all photogs of Yesterday is Here by Daniel Berube ’21.

Courtesy MassArt. (3)

Installation views at MassArt Art Museum, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Boston, MA

I have once again invited my good friend in Boston, Pamela Allara. to provide a post! The shows are up until the end of December.

The gallery at Massachusetts College of Design in Boston has always held innovative exhibitions, but in an inadequate space that frequently dulled its impact. In February, 2020, MassArt Art Museum,(MAAM) held a grand opening for its new gallery, a large, airy, two-story space with its very own entrance for the first time! Unfortunately, March, 2020 followed closely thereafter, and the beautiful space has been closed until its recent re-opening on October 9.

Don’t miss the two exciting exhibits now open, one in the lobby/reception area and the other in the main space. They are well worth a visit both for their intrinsic aesthetic value and for the introduction they provide to the work of less familiar artists.

Ghost of a Dream is an artists’ collective based in Wassaic, New York. Led by Adam Eckstrom, GoaD sponsors Art for Artists (www.artforartists.org), an invitational, curated art exchange, as well as an ‘edition exchange’ which includes works for sale. (The latter have been donated to the Southern Poverty Law Center and elsewhere).The collective makes works from ephemera that center, in their words, “on people’s hopes and dreams.”

As the MAAM looks to the future, GoaD reminded visitors that the new exhibition program should not entail leaving the past behind. On the lobby’s walls they installed a collage created from cut-up and spliced-together images from over 30 years of MAAM’s exhibit catalogs and announcements. Combined into geometric patterns on the wall, they created a handsome, site-specific installation, “Yesterday Is Here,” that caused the viewer to pause and acknowledge the important work the gallery has done before seeing the new work in the main space.

The multi-media work installed upstairs, “Valkyrie Mumbet,” is both monumental and intimate. Its tentacles spanning the entire two-story gallery almost like a giant octopus, it might have been threatening if it were not apparent that the delicate artwork had been constructed out of crochet, embroidery and fabrics, including capulanas from Mozambique, where the artist’s parents grew up. Also known as African wax print or Dutch Wax cloth, European traders mass-produced and profited from capulanas, but more recently they have been reclaimed by local designers in Mozambique. As the exhibit label points out, the cloths “…exemplify the fluidity of cultures and reflect a complicated and intertwined history of cultural exchanges across continents, as well as the legacy of European exploitation, colonization, and slaveholding.”

Vasconcelos is among a number of contemporary artists using fabric and crocheted cloths in their work to reference culture and history: Ernesto Neto, Ibrahim Mahama, Nick Cave and Olafur Eliasson, among others.

When the gallery, which is on the second floor of the building, was renovated, the 1906 steel vaulting and girders were exposed, which allows artwork to be suspended from the ceiling, as in this instance. From below, “Valkyrie Mumbet” seems to float, increasing the sense of its delicacy.

As we approach for a closer look at the ‘tentacles,’ the variety of the swatches of hand-embroidered and crocheted fabrics remind us of the history of women’s craft work, undervalued for its historical and aesthetic significance until recently. Clearly these fabrics have stories to tell us, but what are they? It will be important to read the label more carefully than usual. So much for skimming!

The work is part of Vasconcelos’ ongoing Valkyries series, which honors inspiring women and has been shown at the Venice Biennale and other prominent venues.

Surprisingly, this is the first U.S. exhibit of any of her multi-media work. When she was approached by Lisa Tung, Executive Director and curator at MAAM to create a site-specific installation, Vasconcelos requested information about notable women from Boston’s history.

According to the account of the staff they provided her with

“a list of individuals whose legacies include suffrage, poetry, charity, cycling, nursing, and activism among others. Vasconcelos was strongly drawn to Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman’s story and wanted to honor her. This monumental installation is the artist’s own distinctive homage to Freeman”

Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman, was an enslaved woman who in 1781 sued the state under the Massachusetts’ Constitution’s Bill of Rights, which stated that “all men are born free and equal.” Between 1764 and 1780, 30 enslaved people had sued for their freedom citing the Constitution, but Freeman was the first to sue under a ‘natural right to freedom.’ Despite the fact that slavery was still legal in Massachusetts, and moreover, “men” meant white men, she won her suit and was freed.

Subsequently, she purchased a home in Stockbridge, MA, where she lived comfortably until her death in 1829. Her eloquent statement explaining the reason for her suit is memorable: “Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told that I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it, just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman, I would.”

Given the context, the fact that the work floats rather than being adhered to the flooring, and that the tentacles reach out and up, even to the second-floor balcony, underscores the theme of seeking freedom. Again, in that context, each patch of fabric or handwork becomes the record of an enslaved individual, part of their clothing or of cloths used for cleaning, as well as fabric referencing colonial histories. History is made concrete.

This entry was posted on November 11, 2021 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Feminism, Uncategorized.

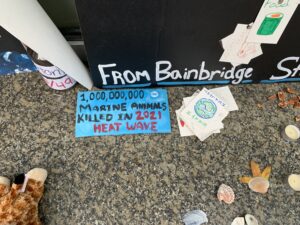

Youth Climate March in Seattle October 29 A Great Success!

Yesterday’s march entirely organized by youth and featuring speakers who were almost all BIPOC, was beautifully organized by them as well as carried out.

We started at Pier 62 on the waterfront. here is the beginning with

both a land acknowledgement and a song/prayer by a native youth.

The signs were really good.

Inaction will kill us

Here I am with one of the terrific signs.

There was some important information handed out about the fraud of carbon cap and trade, and the huge pollution from the military.

We marched up first avenue up Union to Chase Bank, one of the funders of the pipelines. We had speeches, songs, and a die in. The Seattle Times managed to put a photo on the front page without including Chase Bank in the background, it showed mainly knees!

Here is where we lay down ( not me). Then I took a video, hopefully coming soon

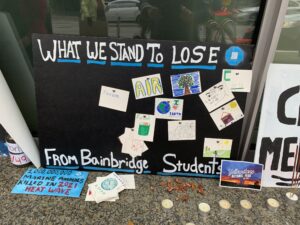

There was more beautiful singing, and then we made a memorial in front of Chase Bank to all we are losing . I contributed a small ceramic grasshopper. Maybe you can see it in the midst of the candles. I was just reading about how many insects are disappearing.

Here is the memorial with some details. It was really moving. ( There were a few cops with bikes standing by and I heard one of them say, we are preventing the windows from being smashed, and we will stay until maintenance cleans this up. I guess they don’t have any children)

Impressive sign with Paul Cheroketen Wagner’s image

in the middle

then we went on to Liberty Mutual Insurance Company. they are insuring the pipelines that are going through native lands all over the place, including most famously in Northern Minnesota with the horrific line 3. the second image is some street theater with Emus sticking their heads in buckets of tar sands, then convincing the employees of Liberty Mutual that they have agency to do something, and finally freeing the emus.

Below is a young Tlinglit woman was really articulate about resisting pipelines. I am hoping to make You Tubes of my video recordings and add them to the post, as the songs and speeches were really eloquent.

This entry was posted on October 30, 2021 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Firelei Báez, To breathe full and free

Pamela Allara, Ph.D., my colleague in art history and all things, contributed this post about a stunning exhibition in Boston.

Firelei Báez’s installation, “To Breathe Full and Free: a declaration, a re-visioning, a correction…” at the Institute of Contemporary Art’s Watershed gallery was one of the most exciting exhibitions that the ICA has mounted in the three years since it opened at this location.

The artist at work on her monumental installation

It is certainly the most memorable.

Firelei Báez was born in the Dominican Republic in 1981. Baez’s mother is Dominican and her father Haitian. Because the Dominican Republic was settled by the Spanish, and Haiti by the French, there has always been tension between the two countries. It is this unsettled history that Baez brings to the surface in her installation.

In the main exhibit space, a monumental series of arches rise up from the marina where the Watershed is located.

Firelei Báez, To breathe full and free: a declaration, a re-visioning, a correction (19°36’16.9″N 72°13’07.0″W, 42° 21’48.762″ N 71°1’59.628″ W), 2021.

Firelei Báez, To breathe full and free: a declaration, a re-visioning, a correction (19°36’16.9″N 72°13’07.0″W, 42° 21’48.762″ N 71°1’59.628″ W), 2021.

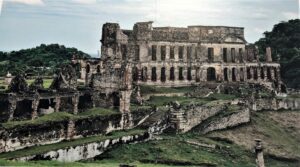

From the color photograph at the exhibit’s entrance we learn that the installation references the ruins of the Sans-Souci palace in Haiti. Sans-Souci was built by Henri Christophe, a former slave. He became a revolutionary general who crowned himself king. He is part of the heroic history of Haiti as the site of the first successful revolt by slaves against a colonial power in this case France.

The palace itself was destroyed by an earthquake in 1843, its ruins a potent symbol of the region’s turbulent history.

Sans-Souci Palace, 1813. Haiti

The artist created a smaller version of Sans Souci on the Highline in 2019

Báez further layers that history with Boston’s own. As one approaches the Watershed space along Marginal Street in East Boston, one passes the decaying former docks on the harbor where for two centuries Boston entrepreneurs actively traded goods, including until the early 19th century, human goods.

As generally told, Boston’s history is a triumphant one, emphasizing the shedding off of oppressive British rule, but Baez reminds us that history is often more complex, and more morally conflicted.

Ironically, Báez was told when she was growing up that as a Dominican, she had no history. The installation makes clear that we all carry histories with us, and it is important to acknowledge and reflect upon them.

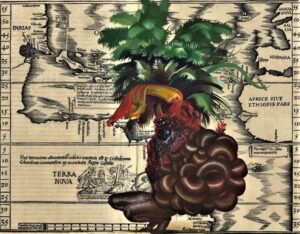

On the entry wall, has painted a large, impressive mural. On the upper left is an inset reproducing a 19th century map of “Boston Harbor and ‘The Sea of New England.’” – the artists fascination with maps has appeared in other works as here

The waters of the harbor, occupying the majority of the mural’s space, are appropriately turbulent, and on inspection one finds that immersed in the waters is a map of Boston and Cape Cod. It also includes the barnacles so common in the nearby waters.

Below the map, Báez has painted a large bouquet of marine flora, ferns and feathers, all native to the Caribbean.

She has stated that the bouquet also contains a mythological figure from Dominican folklore, Ciguapa; perhaps those are his wings we see at the top of the image. Where one would normally find texts and images provided by the curator, here we have a seascape whose history we must attempt to navigate before entering the main space.

Once, there, we leave Boston and its maritime history behind, and are plunged into a different space altogether. As if rising from the ocean floor itself, a monumental ruin punctuated with arched openings she constructed in the space from foam, plywood and plaster tilts across the space. A pierced blue fabric draped from the ceiling provides the illusion that we are perhaps underwater. The sense is both unsettling and exhilarating. One is drawn to walk through and around the arches in order to get a feeling for the palace it references.

But as with all ruins, much is left to the imagination. We must reconstruct this history on our own. The blue references the ocean, to be sure, but also, according to the artist, the valuable indigo dye used by the Yoruba in Nigeria for their cloth, which brought them wealth through its trade.

The history of this trade is explored in the accompanying installation by Boston artist Stephen Hamilton. The images Baez has screened onto the structure initially hold some clues, but why a lion and a panther, neither native to the Caribbean, obviously, and what do the abstract symbols refer to?

This civilization remains obscure and remote, and what’s left of its history, as indicated by the barnacles that ring the bottom of each arch, is decaying. But before the arches sink back into the (ocean) floor, we are drawn to repeatedly walk in and around them as if they might reveal the cause of the structure’s demise. Of course, as we walk, it is impossible not to ponder the decline of all past civilizations and the inescapable fact that our own seems to be on the same trajectory.

Even though this is a created ruin, I found it as compelling as visiting actual ruins. Why do we go to Knossos or to Chichen Itza? For me, and I suspect for most visitors, they bear witness to human creativity, which endures even as civilizations decline. Thus, the monumental architecture is a metaphor for human achievement in general. And finally, the works, even in their ruined state, are beautiful, and in their beauty, remain inspiring.

Photo Credits

Artist Portrait Antoine Boontz

Artist at work, and Untitled Terra Nova: Amani Willett for The New York Times

Installation view, ICA Watershed, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photo by Chuck Choi. © Firelei Báez

Close Up of Sans Souci arches Jesse Costa/WBUR

Mural details and Sans Souci on the Highline Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photo by Chuck Choi. © Firelei Báez

Barnacles Pam Allara

This entry was posted on September 18, 2021 and is filed under Art and Ecology, Art and Politics Now, ecology, Uncategorized.