Imna Arroyo: Immersed in Yemaya and Iroko Water and Life

Imna Arroyo’s work, taken as a whole, creates a puzzle of intersecting chronologies, which appear to form the subjective representation of an aesthetic philosophy that reaches toward celestial planes. Humberto Figueroa Iroko, Tree of Life, p. 56

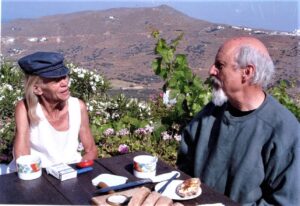

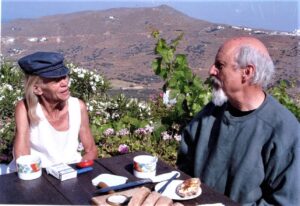

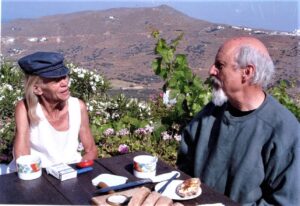

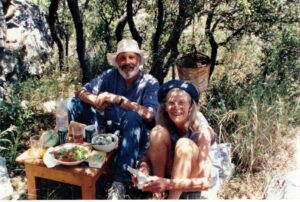

Imna Arroyo bridges art and spirituality in a deeply personal and effective art. She embraces several large themes in her work, that she rethinks and alters each time she creates an installation. Thse two portraits capture two sides of Imna Arroyo, her connection to art and her connection to nature.

Of African, Taino and Spanish heritage, Imna Arroyo is an Afro-Puerto Rican artist deeply committed to acknowledging her multiple heritages and to transforming that heritage into a contemporary artistic statement. Throughout her career she has consistently reached beyond her current work to the next level of creativity, complexity and technical proficiency. She has never settled for a formulaic answer, a single concept, or even a single media. As a result she tells a layered story of her life that resonates with history, place and spirituality. She frequently turns to the symbolism and language of Yoruba poetry, proverbs, legends, myths and imagery.

As an artist printmaker Arroyo has had an exceptionally rich training, as she constantly explores new techniques.

As a young woman in the 1960s she studied with José Alicea in Puerto Rico. After coming to the United States , she earned a BFA from Pratt Institute in 1977 studying with Michael Ponce de Leon and Robert Blackburn. Only two years later she completed an MFA at Yale University. With Gabor Peterdi and Winifred Lutz and later Krishna Reddy she further explored etching, aquatint, and color intaglio techniques. In the ’80s Arroyo moved onto mixed media, multi-color Japanese traditional woodcut techniques with Francisco Patlán in Mexico, and aluminum plate printing at Tamarind Institute.

Part I

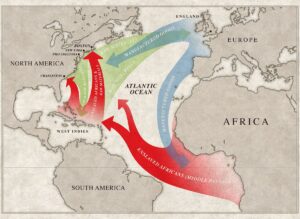

The Middle Passage

Starting in the late 1500s more than 12 million Africans were transported as slaves from Africa to the Caribbean, then sold for sugar and other raw materials to take back to Europe. The horror of this crime is so great that we are all still processing what it means.

Many artists of African descent address this topic from different perspectives.

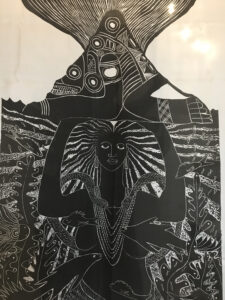

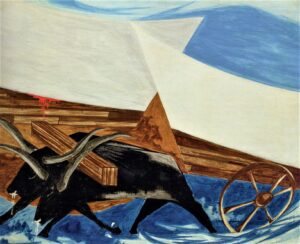

Imna Arroyo’s major installation Ancestors of the Passage focuses on those who did not make it through the three week voyage in unspeakable conditions

Those who were sick or died were simply thrown overboard. Ancestors emphasizes the spirits of those who died, making them visible in prints and sculptures. She speaks to the presence in the lives of those who survived in memories and cultural practices that came to this country.

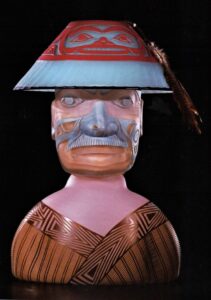

Ancestors of the Passage overwhelms and embraces us with its striking blue sea on the floor, the ceramic busts and hands of those lost in the sea, and a series of prints that cover the walls with haunted faces.

As the artist describes it

Ancestors of the Passage: A Healing Journey Through the Middle Passage is composed of twenty-seven life size terracotta ceramic figures each extending their (54) hands reaching out to the audience. The figures are in a sea of acrylic canvases and blue and green silk fabric, surrounded by (60) black and white collagraphs representing a multitude of people witnessing the journey. The terracotta figures depict the African ancestors that died and are coming back to tell us to remember our gifts. This artwork attempts to gives a visual voice to the untold story of the millions of people who died during the Atlantic crossing.

Arroyo’s awakening and exploration to this horrendous act came when she visited the Door of No Return in Ghana:

In 1997 I traveled for the first time to Ghana. It was at the Elmina Castle, standing in front of the Door of No Return that I had an epiphany that we are all part of a spirit continuum. It was an experience that made me aware of the ancestral realm and forever changed my perception of time and space.

In 1999 she created a series of watercolor paintings called Prelude to the Door of No Return with doorways evoking the shape of the original Door of No Return in Ghana. The artist filled the space of each door and the space around it with references to the Middle Passage, bodies, hands, slaves packed into ships. We can see the roots of the larger Ancestors installation in these abbreviated references.

The Prelude to the Door of No Return was reinstalled in “After Spirituality” at the Fitchburg Art Museum from February to September 2020, at the height of the pandemic. It was paired with an altar with a segment of the Ancestors installation to honor those who died in the Middle Passage as well as in the pandemic.

Trail of Bones

Arroyo has another moving installation referring to death in the Middle Passage, Trail of Bones, an immersive experience in which floor to ceiling black and white prints hover over us. We experience the spirits of those who died and those who survived. A moving video of Trail of Bones appears on her website.

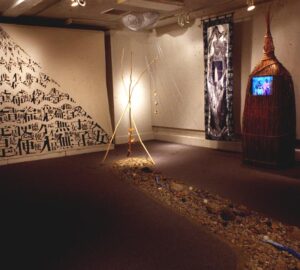

Voices of Water Installation with streambed by Arroyo

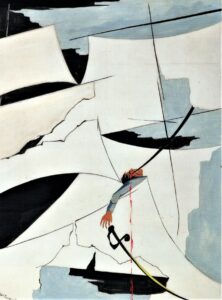

Arroyo began exploring Yemaya, Goddess of Water, as a theme in her work in the summer of 2001. It is a logical step from exploring those who drowned in the sea during the Middle Passage to invoking a spiritual presence that both looked over them and looked out for the survivors.

The video The Many Faces of Yemaya first appeared in 2001 in an exhibition “The Voices of Water” in Oregon and the Czech Republic, a collaboration among several artists including Native artist Gail Tremblay.

The video was the partner to an eight-foot-high expressionist woodcut of the sea goddess, the archetypal great mother, printed on satin (visible on the right in the image). The video and the woodcut invoke the seven avatars of this divinity. Yemaya is a deity of orisha worship that originated in Nigeria and later came to the Caribbean and the Americas.

“Voices of Water” was a crucial turning point for the artist in both multimedia and interdisciplinary collaborations, which is still a central part of her work. Her interest in Yemaya has expanded in many directions.

Initially the artist explored the meaning of Yemaya in books such as Yemaya y Oshun , Kariocha, Iyalorichas y Olorichas by Cuban anthropologist Lydia Cabrera. Then she herself engaged with the spiritual practice. In the summer of 2005 Imna Arroyo was initiated into the Lukumi tradition in Cuba.

She received the honorary title of Chief Imna Arroyo/Chief Yeye Agboola of Ido Osun, (Chief Mother of the Garden of Honor) conferred by his Royal Majesty Aderemi Adeen Adeniyi-Adedapo, Ido-Osun, Nigeria, West Africa the morning of his 50th birthday in 2007.

The House of Yemaya woodcuts are printed on fabric framed with Batik cloth. Yemaya is depicted as a mermaid on the inside and the Virgin of Mercy on the outside referencing secret relationship between the African and Catholic religion practices in Cuba.

House of Yemaya installation

The Many Paths of Yemaya is a multi-media installation composed of seven panels 2’x 8’ woodblock prints and floor installation recreating the Atlantic and the Caribbean oceans made of fabric batiked by the artist accompanied by handmade paper sculptures, shells, glass, wood sculptures. The panels are printed on Satin and framed with Batik fabric from Ghana, West Africa. A six-minute video is also part of the artwork.

The Many Paths of Yemaya 2000-01

Yemaya floats in midair in the installation Legacy: Ancestral Thread Series:

Arroyo describes it:

The installation is composed of five African Orishas or Deities that served as guardians to the ancestors while they were crossing the Middle Passage: Trans Atlantic slave trade. Those who survived the journey brought their multitude of memories from the homeland. My work attempts to re-capture these memory fragments of the Diaspora, weaving together the legacy.

We see the five Orisha busts, three males Elegua, Obatala & Shango and two females, Oshun and Yemaya, made of wire mesh, abaca fiber, hand-made cast cotton pulp suspended in mid air, as memories suggested by small pieces of cotton pulp flow from them down to the floor. Underneath are boats of the same materials.

This work suggests survival, even rejuvenation, through memory and spiritual searching. In some installations the sculptures pair with prints depicting The Journey, small boats with figures, protected or sometime carried by an image of a goddess.

The artist reinstalled Legacies in 2020 in the Coral Gables Museum in the exhibition “Alien2020nation” from December 2020 to March 2021

The catastrophe of the slave trade, the Middle Passage and the protection of the Orishas for those who survived and brought memories of their culture with them, brings us directly to the ongoing tragedies of our contemporary world.

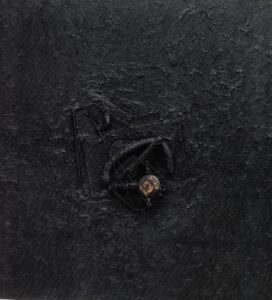

A recently completed diptych, Thorns and Roses a message from the ancestors speaks of our last two years. Two small house-like structures stand on collagraph prints filled with the eyes, perhaps of those drowned in the Middle Passage, or those of more recent tragedies) In one house a thorny stem invokes the pain of life, in the other a rose represents the gifts or blessings discovered throughout these past seven months of COVID-isolation. It appeared in the exhibition A isla miento (Isolation), November 2020 shown in San Juan Puerto Rico, an invitation to artists to address the pandemic. Outside each house stands a cut out women, the artist.

As she explained:

we can choose in our isolation to be safe inside or to feel freedom, to be sad or to be angry.

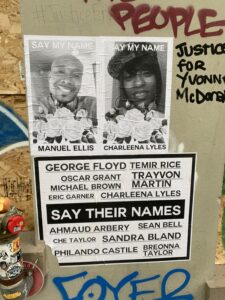

In the midst of the quarantine, we witnessed the public lynching of Mr. George Floyd, even as more young black bodies were killed by police violence. We continue to see displays of white supremacy, people without the sheets or burning crosses gathering in the streets.

Experiences that seem way too common for the African ancestors who endured violence perpetrated against their black bodies for generations stretching over 400 years. Here, experiences emanating from hate, supremacy, exploitation, greed and inhumanity are the thorns. While the strength and genius of the people are inherent gifts bestowed by the ancestors to navigate uncertainty and overcome adversity, here is the rose.

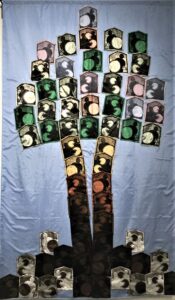

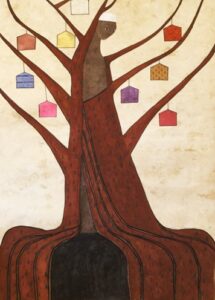

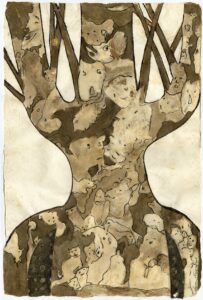

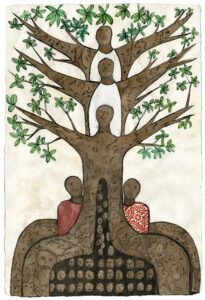

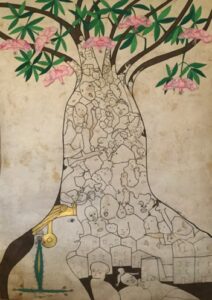

PART II IROKO TREE OF LIFE

At the same time as these works pairing the Middle Passage with the Orishas, Imna created a series based on “Iroko, Tree of Life.” It culminated in a multimedia collaborative exhibition in 2017, and it is still going through new iterations. The 2017 exhibition included prints of the Ceiba, Tree of Life that depicted its transformation in various cultures.

Humberto Figueroa, the curator, describes the installation

“The Iroko installation draws us into a dense thicket of vines that

multiply through the effects of their shadows. Among the twisted

branches, we can make out the silhouettes of simple pitched-roof

houses, typical of the working-class and poorer households of

the Caribbean. The houses in this installation represent the axes

for the divine forces from the Yoruba religion. The deities called

Orishas are represented in the Iroko, and these framed spaces

are meant to signify presences that are intangible and invisible

to the naked eye. The installation extends upward with the

incorporation of numerous other houses in which we see open

palms suggesting supplications to the celestial plane or invocations

to ancestors whose remains reside beyond the horizon. The tree

trunk is suggested by a clustering of houses peopled by inquisitive

eyes and other hands containing faces.

At the foot of the tree, representations of the Orishas can be seen on the floor. The general harmony achieved between the balance of materials and the techniques of engraving and sculpture in an evocative spatial arrangement instills a sense of serenity that is also conducive to multiple interpretations. The Iroko installation is a comprehensive visual text inspired by spiritual expressions filtered through time, other cultures and contexts.”

working on the plywood plate of Yoruba Gaze

Yoruba Gaze Installation

Iroko in the House of the Orishas

Baobab Tree of Life of Africa

Odudua Obbatala Chango Agayu Sola

Yoruba Sacred Tree in the Antilles

Transcendental Ceiba

Yaxche Sacred Tree of Maya

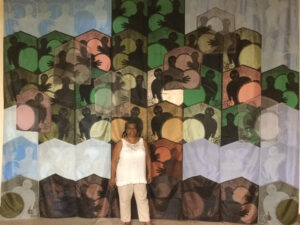

The artist in front of the giant print IROKO Tree of Life, Amate paper, clay sculptures, relief print tapestries and handmade paper with encaustic, reed fiber woven sculptures with the multi-media video.

The artist describes IROKO: TREE OF LIFE:

IROKO was inspired by the sacred Tree of Life, known as Iroko to the Yoruba people of West Africa and those of the African Diaspora, Yaxché to the Maya, Kapok in Southeast Asia, Silk- Cotton Tree to Indigenous North Americans, and La Ceiba in the Caribbean, Central and South America. The tree is of great symbolic, spiritual, mythological, medicinal, magical, commercial, ecological and aesthetic import. Through the exploration of materials old and new, traditional and innovative technologies this multi-media installation focuses on the mysteries of nature using the Iroko/ Yaxché/ Kapok/ La Ceiba / Silk-Cotton Tree as an anchor to express the power of nature, its continuity and resiliency which hold the promise for a sustainable future if nurtured and honored.

Arroyo worked in collaboration with graphic and digital media artist, Tao Chen, and video producer, Jaime Gomez. on a video accompanying the huge print

In the video, filmed by Julio Charris, Jaime Gomez interviews the Katanzama Indigenous people of Columbia. It also includes a dance choreographed by Alycia and performed by Sinque Tavares. The music includes traditional Yoruba Orisha songs sung by Amma McKen, Iya Ola and Swahili Henry and a new dance performed Bright-Holland.

Bringing together many voices in the video, as well as the large print, profoundly speaks to our interconnections. As the artist eloquently explains:

IROKO addresses the challenge of climate change by exploring the interrelationship between our external ecological situation, our awareness of the sacred in creation, and our internal relationship with the symbolic world of the soul. IROKO’s intention is to promote art that expresses that complex, diverse and dynamic intersection, while seeking to connect the intellectual, spiritual and practical components of community building and sustainability.*

A part of the “Iroko Tree of Life” joined an exhibition at the ChShaMa exhibition space called AfreeCan in April and May 2021 in New York City.

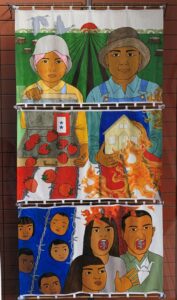

Prayer for a Warrior Island

Currently, September 2021, at the Museum of the Americas in Puerto Rico Arroyo contributed Plegaria para una isla guerrera Prayer for a Warrior Island organized by Las Jornadas del Grabado Puertorriqueño. It was carried in a protest in Puerto Rico.

This print pays tribute to the ancestors of the valiant Taino Indigenous people and the African warriors whose legacy continues to empower their dependents to defend the island from the colonial pirates, imperialists conquistadors, opportunities, embassies, rogues and liars.

We can all immerse ourselves in Imna Arroyo’s extraordinary art works that fuse spirituality, art and nature, with specific resferences based on her own varied experiences. Her carefully thought out prints and multimedia installations can provide us with new hope and perspectives in our present state of climate catastrophe.

Part 3 The Future!

Imna Arroyo: Travesías / Crossings is the title of Imna Arroyo’s current project. It will be a major retrospective, focusing on her interpretation through her art of displacement and migratory flows. Co-curated by Humberto Figueroa from Puerto Rico and Benjamin Ortiz of Connecticut with Yolanda Wood, a cultural critic based in Cuba and visiting professor at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Project , it will be seen at 3 venues: Museo de las Americas, La Casa del Libro in San Juan, in Puerto Rico and Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute in Harlem, New York.

———————————–

All quotes from Imna Arroyo based on our email correspondence, August, September 2021.

*IROKO TREE OF LIFE, Ancestral imprint, the Yoruba Cultural Association from Cuba, 2017. It features essays by ecologist, Carmen R. Cid, art historian, Maline Werness-Rude, and writers Isis Mattei, Maria Vazquez, Esperanza Cáseres Santa Cruz, Jaime Gómez, Migdalia Salas and Humberto Figueroa. The exhibition opened in 2017 at the Connecticut the Clear Gallery, Charter Oak Cultural Center in Hartford and MS 17 Art Gallery in New London.

This entry was posted on September 8, 2021 and is filed under Art and Activism, ecology, Feminism, Uncategorized.

Defusing Radical Alice Neel

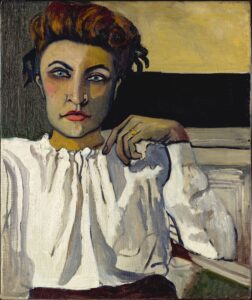

Observe these two portraits

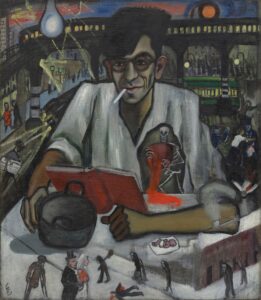

On the right is the feature image of the Metropolitan Museum of Art current exhibition of the work of Alice Neel “People Come First”

It is identified as a portrait of “Elenka”1936, about which there is no information except that she “presumably numbered among the several bohemians with whom Neel associated in Greenwich Village” Neel lived in Greenwich Village from 1931-38 . It was donated to the museum by the sons of the artist.

On the left is “Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis) 1972 – radical feminist and crucial supporter of second generation feminism. Her pose and clothes suggest her radical position, austere colors, monochrome black, unadorned, with a confident leg slung over one arm of the chair, and a single arm raised that shows her unshaven armpit. In addition, Peslikis is famous as a founder of Redstocking Artists in 1971, she co founded the Feminist Art Journal, which also in its first issue supported Neel . The Met catalog finds it curious that the work was titled “Marxist Girl” when, as they claim she was “known at the time not as a Marxist but as a feminist.” But they also mention that she was an early member of New York’s Radical Women, a group that is avowedly Marxist and more specifically and defiantly Trotskyite. The Met catalog says RW is “feminist”. Clearly the Met wants to rush away from any Marxism in the 1970s, just as they want to avoid Communism and Socialism in the 1930s

Elenka on the other hand, wears a ruffled, white blouse, her hand dangles languidly in front of her shoulder without intention. She wears careful makeup. Her face is expressionless and mask like.

The differences are telling: in clothing, in pose, even in the yellow background, which in Elenka is pale and in Marxist Girl is intensely saturated. One woman appears to be static, the other dynamic, so although we know little about Elenka, we can tell she was not an activist from the portrait.

So why did the Met decide to put this portrait on the cover of its catalog? Perhaps because they owned it as a gift from the artists sons, but more important, because it is a mild image compared to Irene Peslikis, it deflates and defuses the radicalism of Alice Neel.

And admirable as this large exhibition is with its many categories, large, intelligent catalog, and memorable array of paintings and documents, that seems to be the overall purpose of the exhibition, to soften Neel’s extremely radical painting, perspectives and position.

Let us look at this quote near the beginning of one essay. It describes Neel as having “a stalwart sense of purpose in her dedication to an ethic of radical humanism”.

Radical humanism? Humanism is the word that these authors have latched onto, (mis)quoting Neel frequently from late interviews.

For example this is an example cited from a comment of 1950 to demonstrate her “humanism” “I have tried to assert the dignity and eternal importance of the human being.”

That of course is not the same thing as humanism!

Then they turn around her radical commitment ” Encounters with socialist and Communist activists in the United States in the late 1920s and 1930s further shaped Neel’s humanism. She joined the Communist Party in 1935 and was intermittently affiliated with the group for the rest of her life.”

To call Communism a shaping of humanism, is indeed an effort to dilute the artists deep commitment to socialism, to presenting what had been unpresented in art, the poor, the worker, the leftist leaders, and so much more.

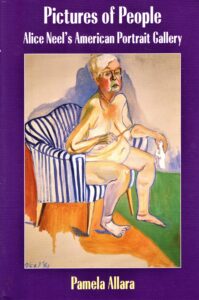

Let us contrast this effort to smooth over Neel’s politics to the ground breaking book on Alice Neel by Pamela Allara, Pictures of People, Alice Neel’s American Portrait Gallery 1998. Allara says Neel “rebelled through both an unconventional life-style and a biting wit, actions and words that indicated an absence of self censorship, a determination to disrupt polite society.”

Allara then brilliantly maps the many types of disruptions that Neel pursued.

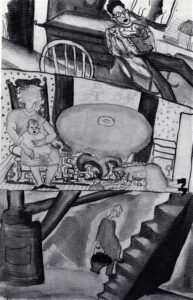

To give one example, In The Family 1927, Neel gives us the antithesis of a happy family portrait. The father slumps over in the basement as he carries coal, the mother lies almost prone on the floor as she wildly scrubs, the mother and baby ( Alice and her daughter) sit oversized in a chair, while the brother in the attic is the oblivious intellectual. Each floor suggests complete isolation. Allara compares it to the sharp descriptions in Sherwood Anderson’s small town stories, while the catalog speaks to the conflicts of motherhood and creativity which of course is not shown here.

Neel’s biggest disruptions in both her art and her life though are still to come as she lived as a single mother in poverty in the Bronx from 1938 – 1962, and in Spanish Harlem after 1962. She was on the Left from the start and stayed there.

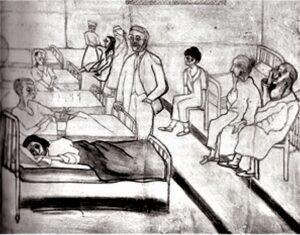

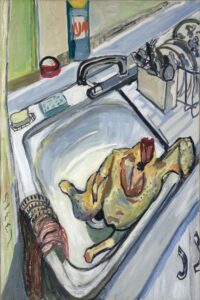

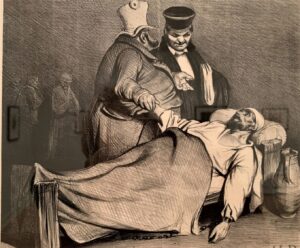

Her depictions of such subjects as “Well Baby Clinic” (left) “Suicide Ward,” (right) give us sardonic information about the failings of the public health system and social services, a subject of great importance today.

Allara’s book is mostly chronological, which makes sense with Neel as her life and her work were deeply affected by dramatic changes in the social and political climate of the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

The Met exhibition had themes ( they don’t appear in the catalog, to which I will return shortly)

Here they are

Introduction

New York City (street scenes, including demonstrations)

Home ( emphasizes her studio as her home, with intimate erotic images) Family is placed here, pretty much the antithesis of “home”

Counter/Culture ( portraits of as the label puts it “individuals who pushed social, political, and cultural boundaries, from bohemian poets and labor organizers to queer performance artists and feminist trailblazers.” So we have the radical leftist Kenneth Fearing above and the cross dressing Jackie Curtis and Rita Redd)

In other words all in one section we have every decade and many different types of people.

The Human Comedy “documenting episodes of suffering and loss, but also strength and endurance, with unsparing candor and acute empathy” The term is based on Balzac’s Human Comedy of the 19thcentury. Here is the Well Baby Clinic mentioned above.

Thanksgiving 1965 was part of Art as History. This section aligned Neel’s work with such luminaries as Robert Henri, Jacob Lawrence, and Chaim Soutine, as well Cassatt, and Van Gogh. Of course this is the most sardonic Thanksgiving image I ever saw.

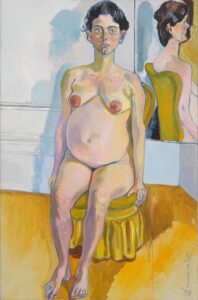

Motherhood includes images of both pregnant women, the famous image of giving birth and mother and child portraits, the term motherhood seems to me a little cozy for Neel’s cutting and incisive portraits

The Nude male and female; these two sections overlap of course and both include pregnant females. Neel’s painting included here of Andy Warhol after he was shot deserves a whole section and essay on its own!!!

Good Abstract Qualities I don’t need to elaborate on why this was here at the end. Sigh, Greenberg rears up.

In other words, these themes obscured social realism in many different places, it spread the pregnant women into three or four places. it grouped different topics together, etc.

The catalog does a better job, with excellent essays by several insightful writers (aside from the smoothing, soothing affect mentioned above). Here are the chapter headings

Anarchic Humanist, Political Creatures, Siempre en la Calle, Ill Show Everyone: An Artist Mother at Home, Painting Fruit(s), Alice Neel’s ‘Good Abstract Qualities’ based on a quote from Neel the year before she died, “I don’t think there is any great painting that doesn’t have good abstract qualities” here elevated to a major theme.

So was this major analysis by some of the best art historians now working at our most prestigious museum trying to sooth us, the audience, the museum board, the Neel family, or were these the positions of the curators and authors. It is hard to know.

At any rate, the main image on the front of the museum gives us a powerful portrait of gay men. As Randall Griffey points out, Neel died right before AIDS devastated the gay community . Several of the people she portrayed died. Griffey points out that she would not have hesitated to paint the ravages of AIDS. So this banner celebrates a moment in our country’s history, before the epidemic, as well as Neel’s own independence in representing gay men and woman throughout her career, in spite of the homophobia of the Stalinists and the Leftists surrounding her.

But unquestionably her radicalism continued throughout her life, (above is The Death of Mother Bloor, 1951 at the height of the McCarthy era, a funeral that she attended) , her feminism was deep seated way before the 1970s, and she continued to radically transform the little regarded format of a portrait until the end of her life. No better example exists than her own nude self portrait at the end of her life

This entry was posted on August 24, 2021 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Feminism, Uncategorized.

One art exhibition

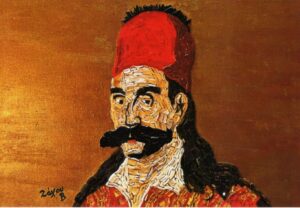

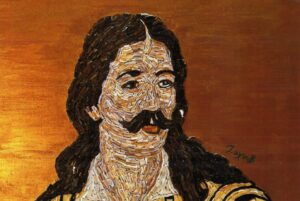

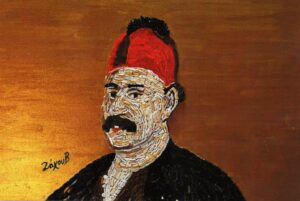

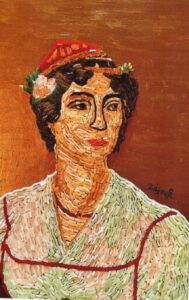

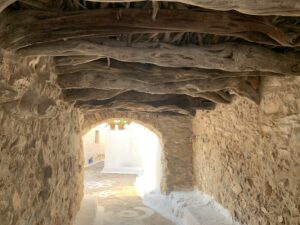

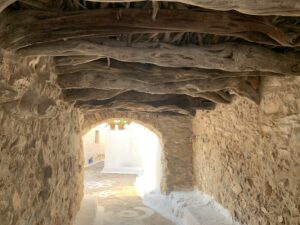

We only went to one art exhibition on Amorgos. The work of Zaxou Vasiliki. You see her here with the poster for her exhibition and the entrance to her small shop . Her exhibition was in the Chora. Her shop is in Langada.

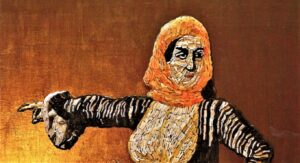

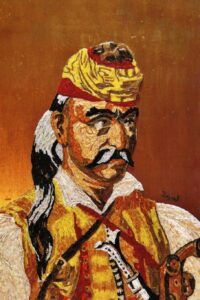

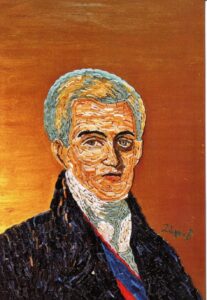

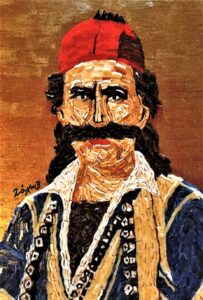

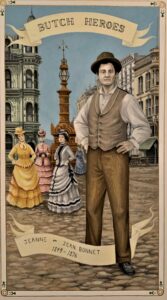

Xazou creates portraits from stained glass that she cuts into mosaic like pieces. This is a series of heroes from the war of

Independence.

The first one is Laskarina “Bouboulina” Pinotsi , a female captain. She lived from 1771 – 1825

.

Theodoros Kolokotronos 1770 – 1863

Jionnis Kapodistrias 1776 – 1831

Odysseas Androutsos 1788-1825

Georgios Karaiskakis 1782 -1827

Athanasios Diakos 1788 – 1821

Andreas Miaoulis

Mantoo Marrogenous 1796-1848

There were many more, but I didn’t manage to get translations of their names.

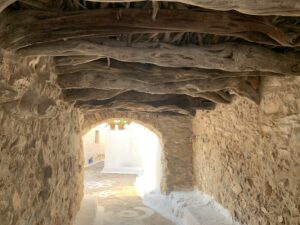

Finally this is a secret Greek school

This entry was posted on August 11, 2021 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Creative Lving in the Cyclades

Of course everyone I spoke of in the last post was creative, archeologists at the museums and the Temple of Demeter, textile artists, potters, Kitron distillers.

In this blog post I am highlighting another creative person,

Sofia Gavala, partner in the stunning Amorgos beach hotel Lakki Village Family Beach Hotel

This hotel is run by the Gavala family. There are five sisters. Here they are when their beloved mother was still alive. Third from the left, near Calliope, the mother, is Niki, who is the business brains behind the Lakki hotel. It started as a vegetable garden then began serving a few drinks on the waterfront, in the early 1970s, next a room or two, next a restaurant, and now it has 65 rooms, a swimming pool, and a delicious restaurant!!!!

Here is the entrance to the hotel, notice the ecological sun shade

We had the great good fortune to stay here for two weeks on our visit to Amorgos to have a memorial to Henry’s sister Carolina.

The hotel faces the beach and the sea, shaded by ancient tamarisk trees, so part of its special feeling is its unique location, hopefully not endangered by climate change. The Aegean sea here is not at all tidal, and they have a high wall between them and the sea, but still the sea did come right up to it at times.

Before I share Sofia’s artistic constructions throughout the hotel, here is the “dining room” and the beach right in front. Picture me on one of those chairs reading and swimming every day!

Here is the view from our room

This is the wing of the hotel we were in. I think it is a newer part,

and the swimming pool with a bar. Every comfort! Gianni, Niki’s son, who is bartender, served me homemade ice cream by the pool.

Now onto the creative art by Sofia. Everywhere in the hotel were her sculptures made from natural materials.

Boats are a theme. There were two at Lakki, but I photographed boats everywhere on Amorgos, both real and models. The one below is a real boat no longer on the water.

The old waterwheel for bringing up water.

A giant root on top of a door

Everywhere we looked we saw signs of Sofia’s creativity, including in the dining room, where the lamps are painted with a Mondrian design

The landscaping was also creative

And of course the hospitality is unmatched. And the cooking delicious. Here we are with Henry’s family on our first night

And finally a walk on the beach at sunset with a view of the ferry coming in to the harbor. Since there is no airport on Amorgos, it still nurtures traditional culture often created by families who have been on the island for many generations. The younger generation is transforming those traditions as well, as I mentioned with respect to the music and the shoemaker’s granddaughter in previous posts.

This entry was posted on and is filed under Uncategorized.

Art, Culture, and Small Museums in the Cyclades

The tiny archeological museums on Amorgos and Naxos were filled with artifacts found on those islands. The intimacy of the spaces, the variety of different types of sculptures, the sense of discovery make visits to these museums delightful.

The first museum that we visited was the Archeological Collection of Amorgos, in the Chora, the old and picturesque capital of the island.

Housed in a former Venetian style mansion, the artifacts documented the long long history of the island. In these photos you see the picturesque courtyard with various artifacts to discover. We even had a guided tour of the inside rooms of the museum!

This is a fragment of a late Archaic grave stele carved by an artist from Paros in the late 5th c BC!

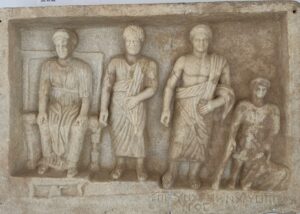

Or below is a Roman relief found in the bay of Aigiali Bay at the other end of the island from the museum

There is even a catalog of the museum by the outstanding excavator Lila Marangou

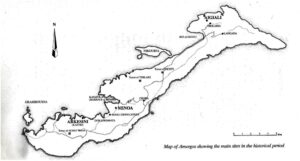

This map shows archeological sites on Amorgos ( hard to see)

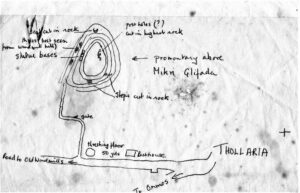

And here is a diagram of a neolitihic site on Amorgos drawn by my sister in law Carolina who lived nearby.

Of course the most famous early Cycladic sculpture of all was found on the island of Keros near Amorgos. It is now in the National Museum in Athens, but there are many versions of it in the small museum on Naxos in their Chora

We also saw fragments lined up in an even smaller museum in the village of Apeirianthos

All of these Cycladic women date to 2800 – 2300 BC. ! Their odd pose with arms crossed across their torso perhaps suggests protection. Also odd is that the face only features the nose, no mouth or eyes.

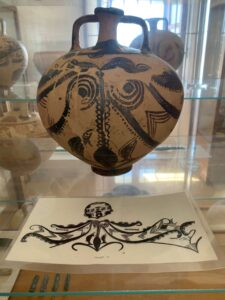

These small museums also had other delights. In the Museum in Naxos we saw many octopus vases, one of my favorite depictions.

We also saw real octopus in front of restaurants. Comparing them to the vase paintings, I think the one in the middle shows the Octopus organs that appear on the vase. Not sure about the anatomy of the octopus!

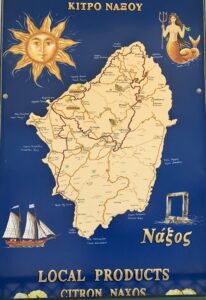

On Naxos we took a tour that allowed us to visit many villages.

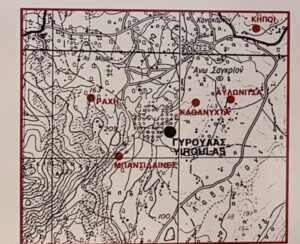

Here is the map of the island.

Most exciting for me was the Temple of Demeter, the only temple we saw on the trip.

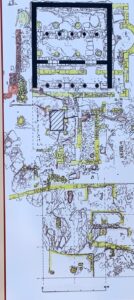

This is a map of the ancient area when the local agricultural people worshipped earth deities such as Demeter on the hill top. They worshipped in the open air with offering pits (brown on the plan.)

You can see the plan of the marble temple here in black, built in the early 6th c BC when the community became more prosperous. Apparently it is an important example of an early classical ionic temple.

In the early Christian period the temple was converted into a church ( yellow on the plan)

The site was excavated between 1994 – 2000 sponsored by the University of Athens and Munich Polytechnic.

In addition to the temple, there was a small museum which I loved because they took a few pieces and showed us where they went, here on the body of a standing man and below on a pediment.

From this stunning temple, we went on to the village of Damalas

where we saw a restored olive press

Our guide explained how it all worked. People pulled the spokes that you see in one photo. You also see the actual press and the pits where the olive oil was probably separated from the water.

Next we visited a pottery studio. The owner explained that he was a fourth generation potter and his daughter in the next room was the fifth generation.

I bought a smaller version of the pot he is holding up, apparently a traditional vessel for drinking wine.

I bought a smaller version of the pot he is holding up, apparently a traditional vessel for drinking wine.

Next a distillery for Kitron, in the village of Chalki. Kitron is a fabulously delicious liquor, I wish we had bought a bigger bottle. They had an intriguing logo of people on a small boat, not sure how that refers to distilling lemons. It was founded in 1896

The founders of the brewery and their three elegant types of Kitron.

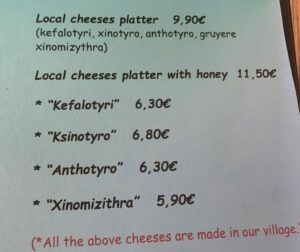

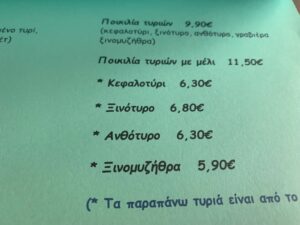

The next stopping place was Apeiranthos, of the small museum mentioned above. The taverna where we had lunch served amazing local rose wine and local cheeses at our lunch.

I copied the English and the Greek to practice my Greek.

These cheeses were incredibly delicious.

In the same village was a women’s cooperative preserving traditional patterns and techniques. The Women’s Association of Traditional Art began in 1987. As the brochure says: ” the traditional cloth is woven on a loom ( seen in photo) with great pride, out of respect towards their ancestors who passed on to them this technique practiced centuries ago, but which is still part of their culture today. ”

Our last stop was the famous so called Kouros still in the mountain side in Naxos. Although nicknamed a Kouros, it is actually an unfinished statue of Dionysus made in the 6thc BC.

We returned to the main center of Naxos for another wonderful day of walking ancient streets and seeing off beat sites. My favorite discovery was this tiny shop “Micraasia” high up on a path leading to the top of the town. She carries creative items such as ecoprint tee shirts and necklaces made from “happy beads” by contemporary artist Yiorgas Syrigas.

But every street is beautiful in the old city center of Naxos

On our last night out in Naxos we ate grilled calamari. Here we are on the way to that dinner.

and one last iconic image

This entry was posted on August 10, 2021 and is filed under Uncategorized.

A Memorial On the island of Amorgos in Greece 2021

We went to Greece to honor Henry’s sister Carolina who died on the Cycladic Island of Amorgos last October. She had a beautiful village funeral the next day.

.

It is a steep road up from the sea to the mountain village of Langada where Carolina is buried in a beautiful small cemetary. Here is her funeral in October.

Here we are gathering in July.

Our event was a memorial at her gravesite. Her gravesite was marked and maintained by loyal friends. It included Henry’s son and grandsons as well as several people from the island. His son made an amazing video of the whole event.

The recollections included that of Irini Giannakopoulos who was one of the young people that Carolina taught English to many years ago in exchange for food. Irini recalled that at that time there was no electricity on the island, and when Carolina tried to teach them the word for ice cream, they had no idea what she was talking about.

Irini is now the CEO and owner of a stunning five star hotel on the island. Two of her sisters run another wonderful hotel, Lakki Village, where we stayed. I will show those photos in my another post.

Another person who spoke was Vangelis Vassalos, also a student of Carolina’s so many years ago. He trained as a doctor in London and is now an acupuncturist and herbalist in the village. He recalled his last night with Carolina, having a cigarette with her and a drink of retsina. He went home and she died in the night.

Henry spoke for himself and his sister in England who could not be there recalling some of their Greek adventures. His son Zac spoke for himself and his two brothers.

After we had a feast and an evening of traditional island music at Nico’s taverna nearby.

The lute player is Giannis (right) and the violinist is Panagiotis. (left) Panagiotis is the youngest member of a musical family going back generations. He played island music with a contemporary interpretation.

You can hear it on the video. right at the beginning.

We spent two weeks on the island and Carolina was very much still with us. I could feel her presence so strongly. Here she is white washing a gateway of Henry’s house which gives you an idea of one of her talents, maintaining three very old stone houses.

She planted many flowers around all the houses

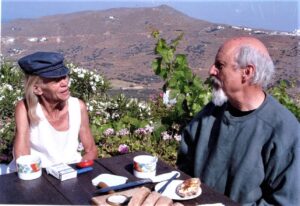

We remembered special times. Here is Henry dancing with Carolina in 1998 after a feast with friends in the platea, the area between the restaurants and stores at the center of the village.

Here is Henry on the terrace of her house on our last night. We spent many evenings at sunset with her here.

She had chosen this village on this island after visiting many islands. It is easy to see why. It is still beautiful and unique. Because it has no airport, it continues to be filled with local culture. Although many of the traditional ways are disappearing, some continue or are transformed by the next generation.

In Carolina’s village the granddaughter of the shoemaker/violinist Stefanikis continues to make shoes, but also designs jewelry .

Photos of her grandfather on the violin playing with Michalis, a dear family friend of ours.

Behind her are the shoe lasts her grandfather used and below is his sewing machine.

Look at the beauty of the streets near her shop.

Another special person is Vangelis, who came to our ceremony. His father was the town baker, his brother runs a wonderful taverna still attached to the bakery where we had our feast after the memorial.

His other brother owns one of the best shops for buying real art, both traditional and contemporary icons, on the island, all three were English students of Carolina.

Vangelis daughter helps to run their shop that sells herbs and delicious mixtures for various purposes made from island ingredients.

Vangelis practices acupuncture here

and distills the herbs here

The olive trees still grow everywhere. Figs also grow wild and sometimes their roots get into the cisterns and block them so they have to be cleared out.

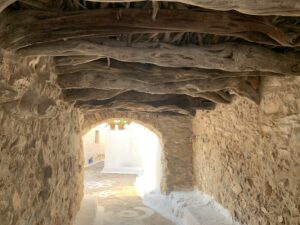

But we also saw very ancient olive trunks holding up passages.

Right outside of the village are the donkeys used mainly now for helping with the olive harvest. They bring up the olives in baskets on their backs but live in these ancient stone shelters.

Going back to Carolina’s story, here is the approach to the beautiful house (on the left) that she restored in the village of Langada and the view from her house to Henry’s house. below you see Henry and Carolina outside his house ( it is actually the roof of the cistern that makes the “patio”.)

Henry and Carolina preparing a meal inside his house in Langada

Carolina also restored another ruin in what was an abandoned village

She walked from her house in Langada to her house in Strombo, across a gorge You can see how rugged the landscape is!

Carolina was amazingly tough and persevering. Near the end of her life she did the walk with two crutches and it took her over two hours. Here is a close up of her house. Very small. Solar electricity!

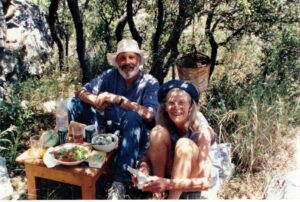

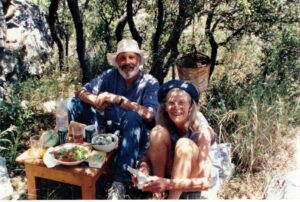

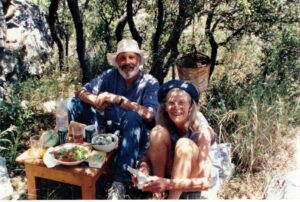

We had many lovely lunches outside her Strombo house. Here is Henry with her and a view of Carolina emerging from the kitchen in her house

As I said her spirit is in the land here.

Here are the musicians playing in her honor.

who died on the Cycladic Island of Amorgos last October. She had a beautiful village funeral the next day.

It is a steep road up from the sea to the mountain village of Langada where Carolina is buried in a beautiful small cemetary. Here is her funeral in October.

Here we are gathering in July.

Our event was a memorial at her gravesite. Her gravesite was marked and maintained by loyal friends. It included Henry’s son and grandsons as well as several people from the island. His son made an amazing video of the whole event.

The recollections included that of Irini Giannakopoulos who was one of the young people that Carolina taught English to many years ago in exchange for food. Irini recalled that at that time there was no electricity on the island, and when Carolina tried to teach them the word for ice cream, they had no idea what she was talking about.

Irini is now the CEO and owner of a stunning five star hotel on the island. Two of her sisters run another wonderful hotel, Lakki Village, where we stayed. I will show those photos in my another post.

Another person who spoke was Vangelis Vassalos, also a student of Carolina’s so many years ago. He trained as a doctor in London and is now an acupuncturist and herbalist in the village. He recalled his last night with Carolina, having a cigarette with her and a drink of retsina. He went home and she died in the night.

Henry spoke for himself and his sister in England who could not be there recalling some of their Greek adventures. His son Zac spoke for himself and his two brothers.

After we had a feast and an evening of traditional island music at Nico’s taverna nearby.

The lute player is Giannis (right) and the violinist is Panagiotis. (left) Panagiotis is the youngest member of a musical family going back generations. He played island music with a contemporary interpretation.

You can hear it on the video. right at the beginning.

We spent two weeks on the island and Carolina was very much still with us. I could feel her presence so strongly. Here she is white washing a gateway of Henry’s house which gives you an idea of one of her talents, maintaining three very old stone houses.

She planted many flowers around all the houses

We remembered special times. Here is Henry dancing with Carolina in 1998 after a feast with friends in the platea, the area between the restaurants and stores at the center of the village.

Here is Henry on the terrace of her house on our last night. We spent many evenings at sunset with her here.

She had chosen this village on this island after visiting many islands. It is easy to see why. It is still beautiful and unique. Because it has no airport, it continues to be filled with local culture. Although many of the traditional ways are disappearing, some continue or are transformed by the next generation.

In Carolina’s village the granddaughter of the shoemaker/violinist Stefanikis continues to make shoes, but also designs jewelry .

Photos of her grandfather on the violin playing with Michalis, a dear family friend of ours.

Behind her are the shoe lasts her grandfather used and below is his sewing machine.

Look at the beauty of the streets near her shop.

Another special person is Vangelis, who came to our ceremony. His father was the town baker, his brother runs a wonderful taverna still attached to the bakery where we had our feast after the memorial.

His other brother owns one of the best shops for buying real art, both traditional and contemporary icons, on the island, all three were English students of Carolina.

Vangelis daughter helps to run their shop that sells herbs and delicious mixtures for various purposes made from island ingredients.

Vangelis practices acupuncture here

and distills the herbs here

The olive trees still grow everywhere. Figs also grow wild and sometimes their roots get into the cisterns and block them so they have to be cleared out.

But we also saw very ancient olive trunks holding up passages.

Right outside of the village are the donkeys used mainly now for helping with the olive harvest. They bring up the olives in baskets on their backs but live in these ancient stone shelters.

Going back to Carolina’s story, here is the approach to the beautiful house (on the left) that she restored in the village of Langada and the view from her house to Henry’s house. below you see Henry and Carolina outside his house ( it is actually the roof of the cistern that makes the “patio”.)

Henry and Carolina preparing a meal inside his house in Langada

Carolina also restored another ruin in what was an abandoned village

She walked from her house in Langada to her house in Strombo, across a gorge You can see how rugged the landscape is!

Carolina was amazingly tough and persevering. Near the end of her life she did the walk with two crutches and it took her over two hours. Here is a close up of her house. Very small. Solar electricity!

We had many lovely lunches outside her Strombo house. Here is Henry with her and a view of Carolina emerging from the kitchen in her house

As I said her spirit is in the land here.

Here are the musicians playing in her honor.

It is a steep road up from the sea to the mountain village of Langada where Carolina is buried in a beautiful small cemetary. Here is her funeral in October.

Here we are gathering in July.

Our event was a memorial at her gravesite. Her gravesite was marked and maintained by loyal friends. It included Henry’s son and grandsons as well as several people from the island. His son made an amazing video of the whole event.

The recollections included that of Irini Giannakopoulos who was one of the young people that Carolina taught English to many years ago in exchange for food. Irini recalled that at that time there was no electricity on the island, and when Carolina tried to teach them the word for ice cream, they had no idea what she was talking about.

Irini is now the CEO and owner of a stunning five star hotel on the island. Two of her sisters run another wonderful hotel, Lakki Village, where we stayed. I will show those photos in my another post.

Another person who spoke was Vangelis Vassalos, also a student of Carolina’s so many years ago. He trained as a doctor in London and is now an acupuncturist and herbalist in the village. He recalled his last night with Carolina, having a cigarette with her and a drink of retsina. He went home and she died in the night.

Henry spoke for himself and his sister in England who could not be there recalling some of their Greek adventures. His son Zac spoke for himself and his two brothers.

After we had a feast and an evening of traditional island music at Nico’s taverna nearby.

The lute player is Giannis (right) and the violinist is Panagiotis. (left) Panagiotis is the youngest member of a musical family going back generations. He played island music with a contemporary interpretation.

You can hear it on the video. right at the beginning.

We spent two weeks on the island and Carolina was very much still with us. I could feel her presence so strongly. Here she is white washing a gateway of Henry’s house which gives you an idea of one of her talents, maintaining three very old stone houses.

She planted many flowers around all the houses

We remembered special times. Here is Henry dancing with Carolina in 1998 after a feast with friends in the platea, the area between the restaurants and stores at the center of the village.

Here is Henry on the terrace of her house on our last night. We spent many evenings at sunset with her here.

She had chosen this village on this island after visiting many islands. It is easy to see why. It is still beautiful and unique. Because it has no airport, it continues to be filled with local culture. Although many of the traditional ways are disappearing, some continue or are transformed by the next generation.

In Carolina’s village the granddaughter of the shoemaker/violinist Stefanikis continues to make shoes, but also designs jewelry .

Photos of her grandfather on the violin playing with Michalis, a dear family friend of ours.

Behind her are the shoe lasts her grandfather used and below is his sewing machine.

Look at the beauty of the streets near her shop.

Another special person is Vangelis, who came to our ceremony. His father was the town baker, his brother runs a wonderful taverna still attached to the bakery where we had our feast after the memorial.

His other brother owns one of the best shops for buying real art, both traditional and contemporary icons, on the island, all three were English students of Carolina.

Vangelis daughter helps to run their shop that sells herbs and delicious mixtures for various purposes made from island ingredients.

Vangelis practices acupuncture here

and distills the herbs here

The olive trees still grow everywhere. Figs also grow wild and sometimes their roots get into the cisterns and block them so they have to be cleared out.

But we also saw very ancient olive trunks holding up passages.

Right outside of the village are the donkeys used mainly now for helping with the olive harvest. They bring up the olives in baskets on their backs but live in these ancient stone shelters.

Going back to Carolina’s story, here is the approach to the beautiful house (on the left) that she restored in the village of Langada and the view from her house to Henry’s house. below you see Henry and Carolina outside his house ( it is actually the roof of the cistern that makes the “patio”.)

Henry and Carolina preparing a meal inside his house in Langada

Carolina also restored another ruin in what was an abandoned village

She walked from her house in Langada to her house in Strombo, across a gorge You can see how rugged the landscape is!

Carolina was amazingly tough and persevering. Near the end of her life she did the walk with two crutches and it took her over two hours. Here is a close up of her house. Very small. Solar electricity!

We had many lovely lunches outside her Strombo house. Here is Henry with her and a view of Carolina emerging from the kitchen in her house

As I said her spirit is in the land here.

Here are the musicians playing in her honor.

It is a steep road up from the sea to the mountain village of Langada where Carolina is buried in a beautiful small cemetary. Here is her funeral in October.

Here we are gathering in July.

Our event was a memorial at her gravesite. Her gravesite was marked and maintained by loyal friends. It included Henry’s son and grandsons as well as several people from the island. His son made an amazing video of the whole event.

The recollections included that of Irini Giannakopoulos who was one of the young people that Carolina taught English to many years ago in exchange for food. Irini recalled that at that time there was no electricity on the island, and when Carolina tried to teach them the word for ice cream, they had no idea what she was talking about.

Irini is now the CEO and owner of a stunning five star hotel on the island. Two of her sisters run another wonderful hotel, Lakki Village, where we stayed. I will show those photos in my another post.

Another person who spoke was Vangelis Vassalos, also a student of Carolina’s so many years ago. He trained as a doctor in London and is now an acupuncturist and herbalist in the village. He recalled his last night with Carolina, having a cigarette with her and a drink of retsina. He went home and she died in the night.

Henry spoke for himself and his sister in England who could not be there recalling some of their Greek adventures. His son Zac spoke for himself and his two brothers.

After we had a feast and an evening of traditional island music at Nico’s taverna nearby.

The lute player is Giannis (right) and the violinist is Panagiotis. (left) Panagiotis is the youngest member of a musical family going back generations. He played island music with a contemporary interpretation.

You can hear it on the video. right at the beginning.

We spent two weeks on the island and Carolina was very much still with us. I could feel her presence so strongly. Here she is white washing a gateway of Henry’s house which gives you an idea of one of her talents, maintaining three very old stone houses.

She planted many flowers around all the houses

We remembered special times. Here is Henry dancing with Carolina in 1998 after a feast with friends in the platea, the area between the restaurants and stores at the center of the village.

Here is Henry on the terrace of her house on our last night. We spent many evenings at sunset with her here.

She had chosen this village on this island after visiting many islands. It is easy to see why. It is still beautiful and unique. Because it has no airport, it continues to be filled with local culture. Although many of the traditional ways are disappearing, some continue or are transformed by the next generation.

In Carolina’s village the granddaughter of the shoemaker/violinist Stefanikis continues to make shoes, but also designs jewelry .

Photos of her grandfather on the violin playing with Michalis, a dear family friend of ours.

Behind her are the shoe lasts her grandfather used and below is his sewing machine.

Look at the beauty of the streets near her shop.

Another special person is Vangelis, who came to our ceremony. His father was the town baker, his brother runs a wonderful taverna still attached to the bakery where we had our feast after the memorial.

His other brother owns one of the best shops for buying real art, both traditional and contemporary icons, on the island, all three were English students of Carolina.

Vangelis daughter helps to run their shop that sells herbs and delicious mixtures for various purposes made from island ingredients.

Vangelis practices acupuncture here

and distills the herbs here

The olive trees still grow everywhere. Figs also grow wild and sometimes their roots get into the cisterns and block them so they have to be cleared out.

But we also saw very ancient olive trunks holding up passages.

Right outside of the village are the donkeys used mainly now for helping with the olive harvest. They bring up the olives in baskets on their backs but live in these ancient stone shelters.

Going back to Carolina’s story, here is the approach to the beautiful house (on the left) that she restored in the village of Langada and the view from her house to Henry’s house. below you see Henry and Carolina outside his house ( it is actually the roof of the cistern that makes the “patio”.)

Henry and Carolina preparing a meal inside his house in Langada

Carolina also restored another ruin in what was an abandoned village

She walked from her house in Langada to her house in Strombo, across a gorge You can see how rugged the landscape is!

Carolina was amazingly tough and persevering. Near the end of her life she did the walk with two crutches and it took her over two hours. Here is a close up of her house. Very small. Solar electricity!

We had many lovely lunches outside her Strombo house. Here is Henry with her and a view of Carolina emerging from the kitchen in her house

As I said her spirit is in the land here.

Here are the musicians playing in her honor.

This entry was posted on August 5, 2021 and is filed under Uncategorized.

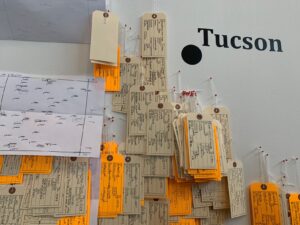

Grief and Grievance at the New Museum in New York

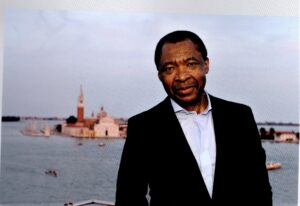

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” ( New Museum February 17 – June 6, 2021) honors the brilliant Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor. Conceived and partially planned before his death in March 2019, the exhibition was realized by a team of curators at the New Museum.

The theme has only become more potent since the fall of 2018 when Enwezor was first invited to create the exhibition.

”Grieve and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” features thirty-seven artists from established to emerging presenting intensely confrontational works that expand the idea of grief in many directions. The partner concept, white grievance, emerges mainly in the catalog essays.

As stated in the press release the exhibition “brings together works that Address Black Grief as a National Emergency in the Face of a Politically Orchestrated White Grievance.”

“White Grievance” is a concept that we can think about. Enwezor starts from the perspective of the Gettysburg address by Abraham Lincoln. Gettysburg is the site of a major defeat of the Confederate army let by Robert E. Lee (July 1-3, 1863) that led to the victory of the Union in the Civil War. Enwezor quotes the entire address in his forward characterizing it as “terse and succinct” in stating “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom “

But Gettysburg and the defeat of the Confederacy also set the stage for white grievance, giving birth to white supremacy and the Ku Klux Klan. Trump held a rally there in October 2016 which Enwezor describes as “a surreptitious attempt to obscure and blur Lincoln’s statement and shape a completely new narrative of American purpose. . . . part of a carefully crafted strategy appealing to white grievance as part of his larger, divisive and white nationalist ideology.”

This clear analysis is further developed in all the catalog essays. First Judith Butler’s “Between Grief and Grievance, a New Sense of Justice,” lays out the gap between loss and the “appeal to repair and rectify that loss.” Butler speaks of the role of photography as a trophy rather than a proof of guilt in a crime. Enwezor refers to it as the “vampiric machine” in reference to pictures of starving children for example.

We have witnessed this year and in many recent years how photography has been used to commemorate and to protest: how it is cropped and edited can condemn or condone guilt, even as it irrefutably shows the facts.

Butler also addresses the difference of grievance for people of color and for white supremacists. For the person of color who is in danger, going to the law can lead to your own murder. The burden of the dangers of functioning without the protection of the law becomes an unbearable constant weight for people of color. That theme is also in Claudia Rankin’s essay “The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning.”

In contrast, as evidenced in the present moment, white grievance declares, as Butler puts it,

“loss of presumptive supremacy discounting the petition to justice in favor of its own challenged sense of power. “

That challenged sense of power, Enwezor argues, has its roots in the Southern defeat in the Civil War.

Since Trump cultivated it at his rally at the site of the Gettysburg loss, it has metastasized all over the country most spectacularly on January 6, 2021. Armed resistance by militias in many states have attacked the capitols of several states, and currently there are widespread efforts to severely limit access to voting for people of color and the working class.

Juliet Hooker suggests in “White Grievance and the Problem of Political Loss,” that Trump’s strategy is “driven by a specific form of racial nostalgia that magnifies symbolic black gains into occasions of white dislocation and displacement.” The result is that when white privilege is in crisis because white dominance is threatened, many white citizens not only are unable or unwilling to recognize black suffering: they mobilize a sense of white victimhood in response.”

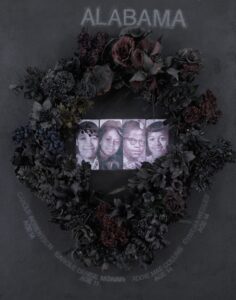

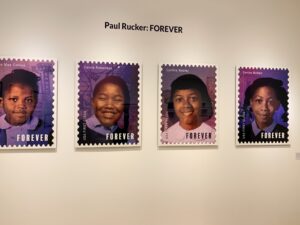

Howardena Pindell Four Little Girls Killed, 2020 mixed media on canvas, Courtesy the artist, Garth Greenan Gallery, and Victoria Miro Gallery.

detail of Four Little Girls Killed

Hooker points out that massive black losses lead to small symbolic losses for whites. So after the murder of eight people at a prayer meeting, the removal of a confederate flag followed.

This huge imbalance continues to the present: “As whites mourn their lost privileges, blacks mourn their dead. “

Boy on the left “Why do you see me as a crime?” and on the right “All Mothers were summoned when George called for his”

Hooker’s essay was published in 2017, long before the great outpouring in response to the irrefutably documented murder of George Floyd murder, yet her words are entirely accurate:

“Racial politics today seem headed for an intractable impasse. On the one hand there is highly visible black and nonwhite grief driven by acts of violence carried out by police and radicalized white supremacists targeting various racial minorities, as well as cruel state polities aimed at immigrants,Muslims and others. Meanwhile there is a large cross section of whites mobilized by a deeply felt sense of grievance and racial resentment. “

Ta Nahisi Coates ”The First White President” doubles down on white supremacism and Trump who “has made the awful inheritance explicit . . . To Trump white is neither notional nor symbolic but is the very core of his power”

But Coates goes much further than that. He speaks of the “bloody heirloom,” the inheritance of white privilege from the founding of the nation.

Then he points out how liberal politicians and journalists separate themselves from the white working class, and point to them as the Trump supporters. When in fact, Coates states, whites from all economic levels supported Trump. The myth of white anti racism is exploded by Coates and he implicates whites in enabling the election of an overtly racist white man. Furthermore, in demonstrating that a demagogue can create havoc without punishment, the Trump example is dangerous (as we are seeing everyday).

But in the end, Coates declares that “there can be no conflict between the naming of whiteness and the naming of the degradation brought about by an unrestrained capitalism, by the privileging of greed and the legal encouragement to hoarding and more elegant plunder. . . . I see the fight against sexism, racism, poverty and even war finding their union not in synonymity but in their ultimate goal – a world more humane. “

These powerful essays together with those of many others in the catalog, constitute the articulate indictment of white privilege as the foundation of white grievance and where we are today.

At the same time that this catalog went to press in 2020, Isabel Wilkerson’s book Caste, exploded on the scene, tracing white supremacy back to the very first arrivals of Africans in the early 17th century. No Europeans called themselves white until they arrived in America, where white became a racial invention to distinguish from black slaves. Being white became the privileged caste from the beginning. It is the threat to that privilege that motivates white grievance today.

Let us turn to the exhibition itself, which is entirely the work of African American artists of all ages. All of them address grief, but in many ways.

The exhibition centers around several anchor works ( as cited in the catalog, although that is not evident in the installation and other works are equally important)

Jean Michel Basquiat’s Procession

Nari Ward’s Peace Keeper,

Daniel La Rue Johnson, Freedom Now Number 1,

April 13 ,1963 -January 14,1964 includes a broken mouse trap, a fexible tube, and a FREEDOM now button, from the Congress on Racial Equality. collected as he travelled through the South “these objects are traditionally used for trapping, cutting and hacking, functions that suggest dismemberment and fracture ” ( catalog p 249)

Jack Whitten’s Birmingham, 1964 (to which I return at the end of the post), aluminum foil, newsprint, stocking and oil on plywood

Ward’s Peace Keeper originally created for the 1995 Whitney Biennial, and re created for this exhibition, deeply inspired Enwezor, according to Massimilliano Gioni.

A giant memorial in the form of a hearse covered in tar and peacock feathers inside a cage, the metaphors are unmistakable.

Mufflers hang in a cloud above it, and rusted metal pipes surround it on the floor, the whole imprisoned in a cage.

Enwezor called it a “tour de force” melding of materiality and spirituality, a combination that Enwezor saw as central to discussion around mourning in African American culture” (paraphrased by Massimilano Gioni). He planned to give a series of lectures on the intersection of black mourning and white nationalism, a crucial concept that has escalated dramatically in the last two years.

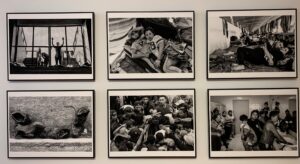

Thinking about the rapidly evolving role of photography in the documentation of black death, the photographers included in “Grief and Grievance” offer a nuanced expansion of the public media’s narrow focus on murder and grief.

La Toya Ruby Frazier speaking in her exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum

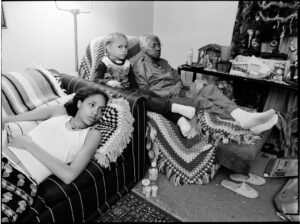

LaToya Ruby Frazier descends from generations of her family who lived and worked in Braddock Pennsylvania, the home of Andrew Carnegie’s first and last steel mill. LaToya‘s grandmother, who raised her, was born in the 1940s when the town was prosperous; her mother in the 1960s, the era of Reagonomics; and she herself in the 1980s, when the war on drugs decimated her family.

LaToya’s series “The Notion of Family” (2001-2014 above) intimately offers us both the love she experienced, and the illness both she her family suffer as a result of toxins in the air and water near the steel plant.

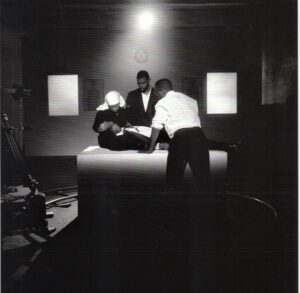

Carrie Mae Weems series “Constructing History” stages famous Civil Rights events with art students. She calls attention to the generic media perceptions of these moments of intense grief and resistance by themes “The Assassination of Medgar, Malcolm and Martin” above or the “Endless Weeping of Women” Clearly contrived images, as is the public understanding of the depth of the feelings that permeated the events, Weems give us grieving as a construct, to underscore how little it is understood.

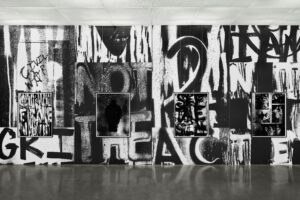

The ground floor of the museum provides intense juxtapositions of media and content that begin the immersion in both grief and resistance throughout the exhibition. Adam Pendleton covered lobby walls in graffiti-like writing that screams at us in messages repeated over and over. “As Heavy as Sculpture” includes words like ACAB (all cops are bastards) and other words taken from protests, combined with his own slogans and photographs of masks and figures to suggest the fragmentation of visual and verbal communications in protests that becomes a type of street poetry.

Also on the entrance floor is Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death first launched in 2016-17 ( detail above) as an extraordinary seven minute homage to black life. Created in rapid jump cuts from many sources, it jolts us between the joy and nightmare of being black in the U.S, set to Kanye West’s gospel “Ultralight Beam.”

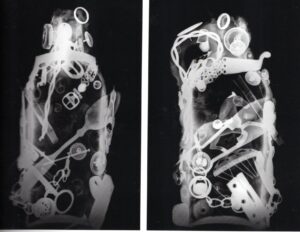

Not far away is musician Terry Adkins’ hugely enlarged xrays of memory jugs, vessels with personal mementos such as rings, watches, jacks, and spoons attached to their outside. Originally physical grave markers, these looming photographs now embody both the ghosts of the original owner of the objects, the ghosts of a long-gone life and ritual, and the ghosts of our contemporary world.

In the same gallery an actual cattle squeeze painted black The Full Severity of Compassion, by Tiona Nekkia McClodden presents its horrifying function, to squeeze cattle before they are killed, like a satanic hug. The psychic and physical immediacy of the squeeze cannot be avoided, even as we recognize a metaphoric level that refers to black lives.

On the second floor, in addition to Ward’s overwhelming sculpture, we see the work of Sabie Else Smith, tiny polaroids immersed in black grounds referring to the photos visitors make of their family members when they visit them in prison.

A video on the ground floor Alone by Garrett Bradley also speaks to the same subject, expanding the experience of visiting a prison to a deeply moving narrative of the life of a young woman left alone, separated from her beloved fiance.

Dawoud Bey’s large paired black and white portraits from his Birmingham Project, 2012 presents one young person at the age of the the four young girls killed in the bombing of the 16th st Baptist Church, and two young men killed in protests that followed. The second image is an adult of the age these young people would be were they still alive. Instead of a one dimensional victim, Bey presents people who are looking straight at us, alive and strong, at the same time that we see the deep pain inside the bodies of both young and old.

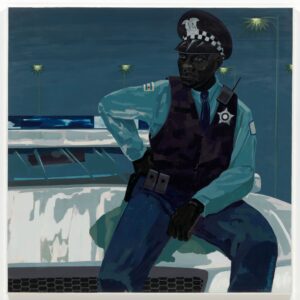

Moving to the third floor, where Basquiat’s Procession, a reference to a jazz funeral, greets us first, then a room full of Kerry James Marshall’s layered collage/paintings that honor the dead. His untitled (policeman), of a black policeman speaks of the contradictions at the heart of survival for black people. Here is a securely employed middle class black man, who is part of an oppressive state sanctioned system. His posture with one hand on his hip, the other on his knee as well as his gaze away from us into the middle distance, as though he sees his own death there, suggest his own fears as well as his professionalism.

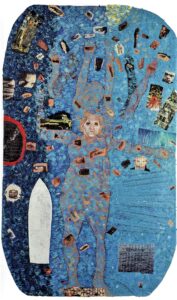

Near the stairwell to the fourth floor is Howardena Pindell’s 1988 Autobiography, Water(Ancestors/Middle Passage/Family Ghosts which I consider one of the benchmark historical works although it wasn’t cited in the catalog. It looms above us with a life size figure multiple arms flailing in water filled with the eyes and heads and hands of so many others. Beside the figure Pindell quotes a document that states that a black man who intervenes when a white man is raping his wife will be killed.

Hank Willis Thomas’s 14,719, hangs in the stairwell –long blue banners covered in stars, each one representing a death by gunshot in 2018. The sudden switch in meaning from an American flag so often used in commemoration of death, here to speak of an almost invisible slaughter, turns a memorial into a scream.

Of course it is impossible for me to write about all the work in the exhibition, much as I would like to enumerate every one. What is striking is the synergy among the works, each speaks to the other, in a continuous narrative. At the same time, these artists all speak of survival, resistance, and defiance. Black grievance emerges as the larger arc of the exhibition, as these works speak out against injustice, invisibility, and the incomprehensible.

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” pays fitting tribute to Okwui Enwezor. It also stands as a celebration of black creativity and the power artists have to make a stand against the staggering racial injustices of this country.

Writing this on the Fourth of July, I can’t help mention the irony of the celebration of independence that was for white men only: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—”

By 1776 over 67,000 Africans already had been brought to the US, the first declared to be a slave rather than an indentured servant in 1654 ( the total would rise to 305,000 by 1876). Apparently Jefferson called for an end to the importing of Africans for slavery in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence: “ He(King George) has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.”

It was removed in deference to the many business men benefitting from slaves.

I conclude with this early work of Jack Whitten, Birmingham 1964 with a photo of police brutality appearing behind peeling aluminum foil a reference to the town Bessemer Alabama, the town where Whitten grew up. The artist left the South shortly after he made this work to have a dazzling career in New York City.

Out of this darkness came light, as I talk about in my review of his show at the Met Breuer in 2018

Let us hope that continues to be the case for this country. Out of our darkness can still come light.

This entry was posted on July 8, 2021 and is filed under Art and Activism, Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Uncategorized.

Jacob Lawrence and “The American Struggle” at the Seattle Art Museum

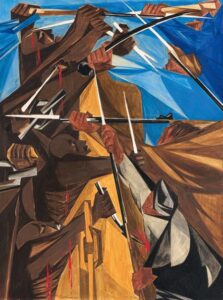

Looking at this single image of the Boston Tea Party the no 3 panel in Jacob Lawrence’s “Struggle: From The History of the American People” we see how radical Lawrence is in every respect: composition, space, color, subject matter. In stark contrast to his well-known “Migration” series, the work from “Struggle” includes dynamic thrusting diagonals and horizontals that shoot across the picture plane, in this case a shallow space. The colors are also striking: neither realistic, pretty or even believable, they tell us of conflict, red, green, of harsh confrontation. The fragmented robes, recalling cubism in the fractured surfaces, also speak of conflict. Nothing in Lawrence’s work is a formal device used for its own sake. Looking more closely we see huge brown hands grabbing the heads of three “Indians.”

All of this in a small panel measuring 12 x 16″.

The caption reads: “Rally Mohawks! Bring out your axes and tell King George we’ll pay no taxes on his foreign tea.” First, although it was a non violent protest, Lawrence reinterprets it as an intense struggle with axes and fists. the caption is from a 1773 protest song. based on the “tea party.”

The so called Sons of Liberty (perhaps a group called that now?) dressed as Mohawk Indians (!) see above, and dumped hundreds of pounds of tea into Boston Harbor. The tea was from the East India company, so also the product of colonization. Dressed as Mohawks meant the Indians could be blamed, and the actual participants melted into the community.

The exhibition of Lawrence’s “Struggle “series couldn’t have been better timed at the Seattle Art Museum. We saw it not long after the January 6 insurrection in the Capital which attempted to overthrow the election and throw the government into turmoil.

That recent struggle invoked the terms of our early struggle for independence from Britain, militia, patriots, minutemen, and it too was motivated by economics. You may recall that the so-called Boston tea party was because Britain wanted to impose “taxation without representation.” Britain wanted to be paid back for helping the colonists during the French and Indian wars. But of course the colonists, like all groups that seek independence, wanted to keep their money and spend it the way they wanted to. They didn’t want anyone taking away their money ( or in our recent case, “their” election)

The rethinking of history in this series begins with Panel no 1 of Patrick Henry. In this incredible image of Henry reaches a long hand over a crowd he roused with equally long arms, saying ” is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? ( 1773)

Henry is better known for his “Give me Liberty or Give me Death” (from the same 1773 speech). By choosing this quote Lawrence immediately reframes the image and the speech as a collective struggle, not that of one person, the energy of the arcing hand seems to radiate toward the crowd, but in the dark sky are drops of blood.

Almost every image in “Struggle” has drops of blood, wounded men, wounded horses, or as here, the sky rains blood.

The struggle is never peaceful. Only death and defeat are quiet.

One of the most poignant images is

number 5 with the caption “We have no property! We have no wives! No children, We have no city! no country!” from a petition of many slaves 1773. This outcry before the revolution underscores that “liberty” is only for the elite few.

It reminds us of the cruelty of slavery in, among many cruelties, breaking apart families (much as the previous President did to immigrants).

Jacob Lawrence started thinking about the theme of Struggle in 1949. He pursued research for five years and started painting in 1954 perhaps not coincidentally just as the high pitch of the McCarthy era was winding down. He planned it as McCarthy was accusing hundreds of Americans of being communist, ruining their careers and their lives. He began to paint in the same year as the Brown vs Board of Education decision , in May, and continued to paint as Emmett Till was lynched in August 1955 and Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in December 1955 and Martin Luther King leads a bus boycott .

He spoke of the series as a history of “all the peoples who emigrated to the “New World.” By transforming it conceptually from his first idea of the history of the Negro people to that of all those who contributed to building the United States, he wanted to show a “constant search for the perfect society.”

This newly recovered image of Immigration (Panel 28) has the caption “Immigrants admitted from all countries: 1820 – 1840- 115,773”

Again, how timely. This is an early era of migration before any restrictive laws began. The first “Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and Alien Contract Labor laws of 1885 and 1887 prohibited certain laborers from immigrating to the United States.” These laws were aimed directly at Chinese laborers building the railroad to prevent them from bringing their families. As those of us who live in the west know well, Chinese laborers were forcibly expelled from towns all over the West.