Ling Chun Apostrophe S

Galleries are slowly reopening. Method Gallery has a wonderful new installation by Ling Chun. When I first saw it, I was confounded.

Ling is a ceramic artist in her training, but what she does with ceramics is so innovative, that she must now be called a multimedia artist at the intersection of pop, modernism, and contemporary politics.

As I looked at this complicated work, with the title, The Neon She Remembered ( 2020), I first had to set aside my own preconceived aesthetic ideas. In her combination of fake pink fur, neon, ceramic purposefully declaring its own glazes ( more on that), Ling comes from an entirely new aesthetic generation. But each element of her work is layered with meaning.

Originally from Hong Kong ( she came here at age 17), Ling learned Chinese calligraphy as a child. She spoke of learning chinese characters, practicing a single stroke all day, to create harmony between one stroke and the next of a single character.

For her ceramics are a symbol of language, that is why you see curved shapes flying off her central form. These are individual strokes of Chinese Calligraphy.

Lets go back to The Neon She Remembered. The neon is itself a complex medium, now archaic, as she has pointed out, with the emergence of LED lights. For her it is deeply associated with Hong Kong as she remembers it from her youth, filled at night with neon street signs. She took a workshop in order to understand how to create neon. Here it seems to wander outside the main structure, creating visual connections between the separate segments. The colors connect to the Hong Kong democracy movement, yellow pro democracy, blue pro government.

That pink and white fur as a base represents perhaps the soft foundation of the current world, Hong Kong, our lives, maybe it is simply a cushion for the piece, giving it an unreliable place to stand. I associate it with the Asian girl fashion that we heard so much about a few years ago ( as in Hello Kitty of course).

Then there is the magenta hair. Ling went to beauty school at some point, but quit, yet she has a life-long love of hair, and here we see it hanging down straight on this female figure.

Is this a self portrait actually, caught between the different forces of the world?

Ling speaks of yearning for home without having a sense of belonging either here or in Hong Kong. She is caught in between, a feeling of so many immigrants. Here she gives us fragments of memories, of who she is, of who she remembers being, of perhaps who she is becoming.

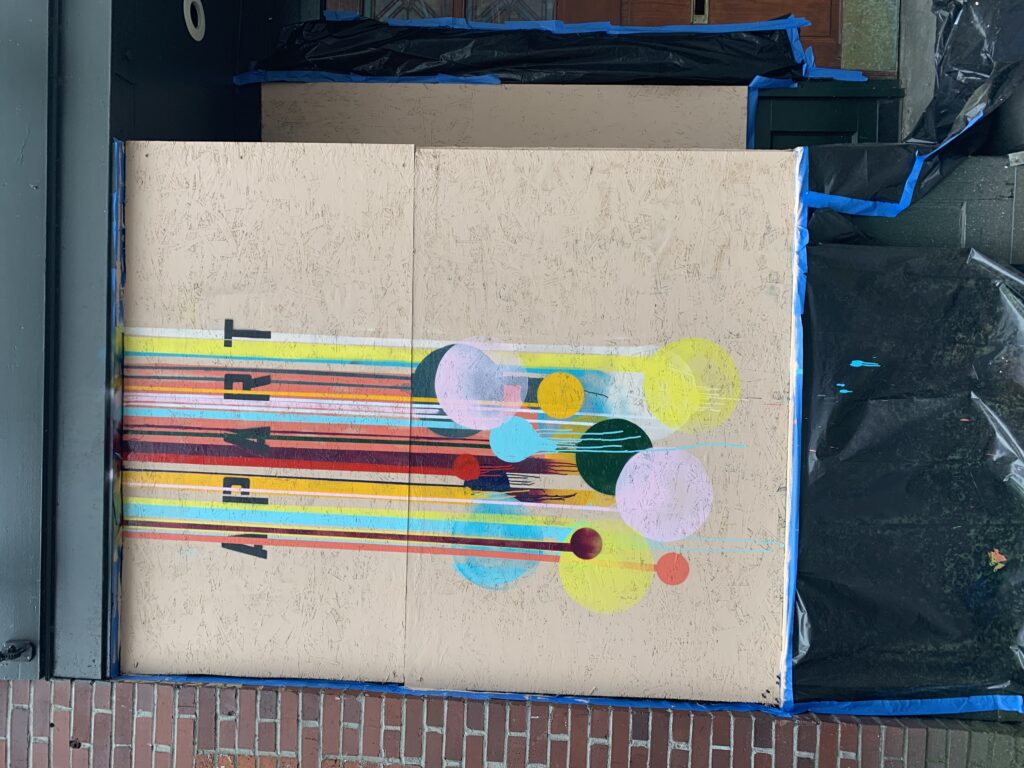

The second large piece in the exhibition Sign/Sigh is an installation. Again blue and yellow are the dominant colors, here on a plywood construction that echoes classical modernism. But plywood as a material is suddenly so prominent in the windows of closed stores everywhere.

The sculptural elements of the squares with balls in a grid refer to Chinese characters. The balls are “signs” ( in both a literal and metaphorical sense of the word) of calligraphy. Chinese square calligraphy is a simplified version of writing in Chinese characters.

Ling stated that the works evoke belonging and memories of home. But they are also expressing our current disrupted world in which all the familiar structures and habits are altered, suspended, cancelled, coming apart, disappearing, or destroyed.

Returning to the ceramic itself, an ancient medium, a modern medium, a medium that can rise up in rebellion, or subside into quiet utility. Here it rises up, literally off the surface. The glazes are individual sculptural elements, they refuse to blend, lie on the surface or subside. They are a churning sea of color and form.

When asked who inspired her, one of the artists that she mentioned was Ron Nagle. Nagle is an old friend of mine from the three years that I taught with him at Mills College. On first glance his meticulous ceramics seem far from Ling’s work, she seems closer to the work of Peter Voulkos, the ceramic artist who broke through the prejudice against ceramics to achieve international acclaim during the era of Abstract Expressionism. Nagle is entirely different, his work is small in scale, but his glazed colors and shapes are layered, surprising and completely unpredictable. As a personality, he is outrageous, and funny. He is also a musician. So he mixes it up too.

Here is Light Me Up Green: pop color and offbeat juxtapositions are crucial in all of her works, and the same is true of Nagel’s work. The surfaces are entirely different, but the juxtapositions of unexpected hues is similar.

The entire exhibition called “Apostrophe S” ( what does the title signify? belonging, not belonging?) is initially alienating then provocative because it provides insights into Ling and her life experience, as well as a window into the chaos of this turbulent moment.

.

This entry was posted on July 26, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

CHOP the Garden

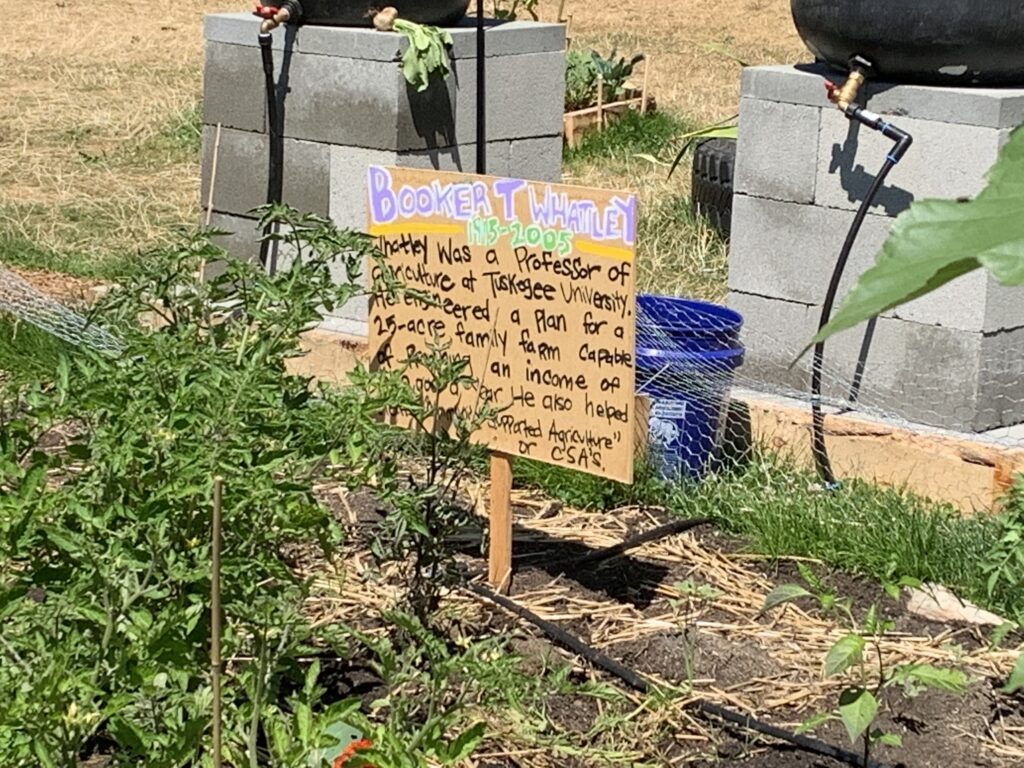

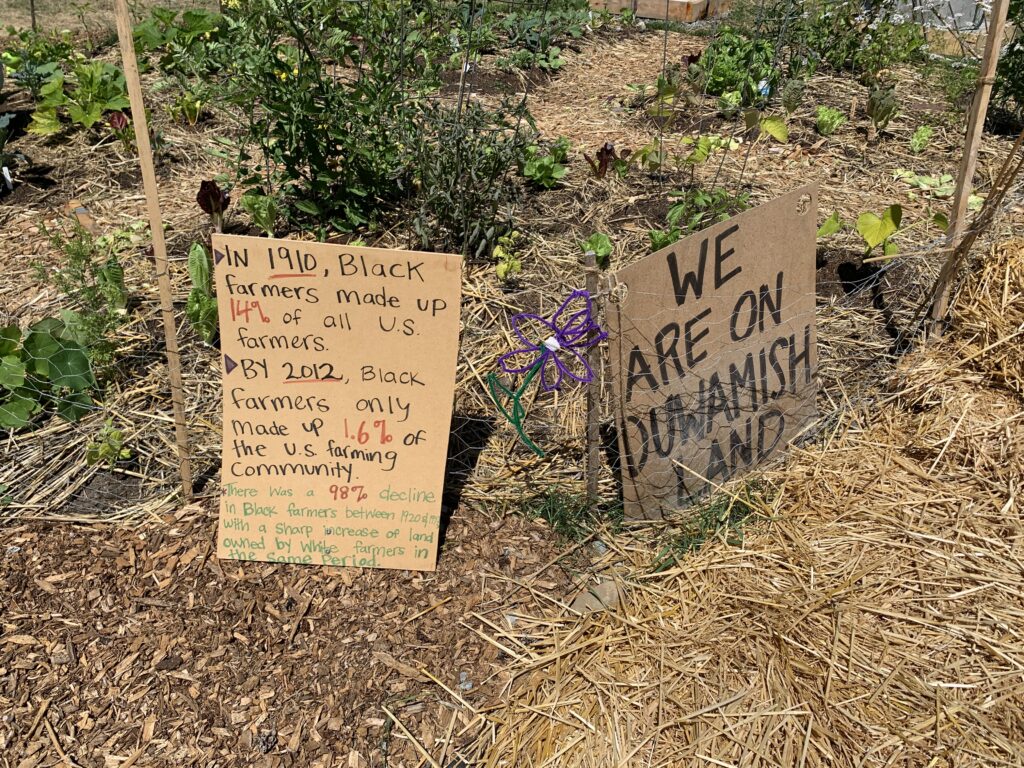

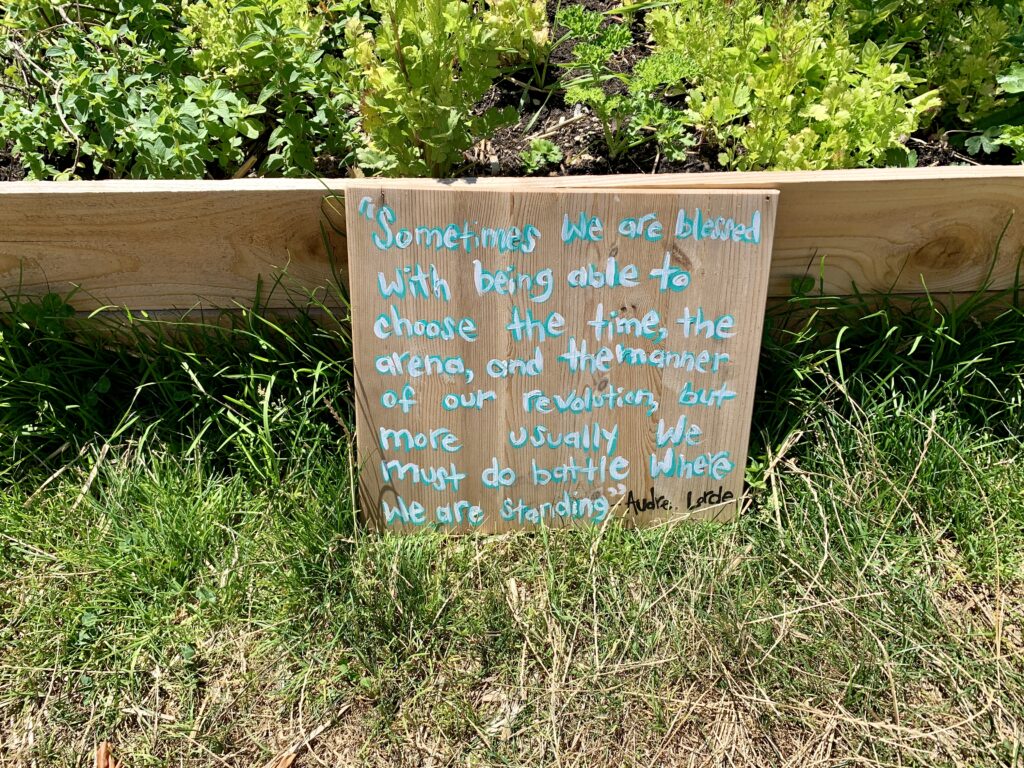

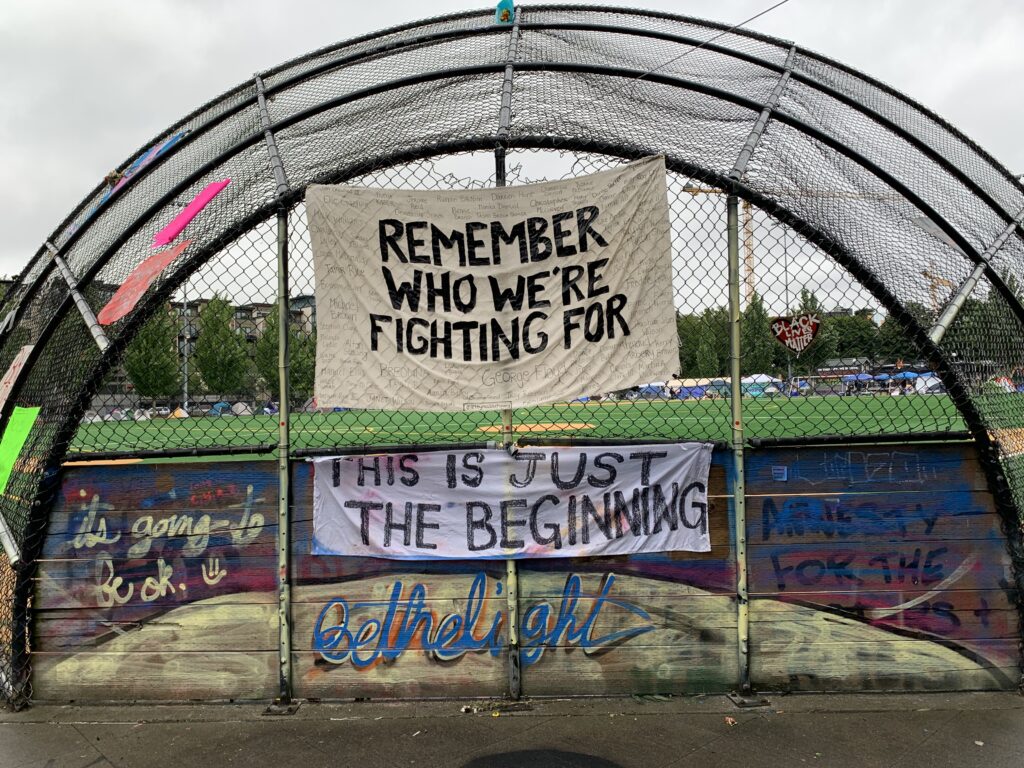

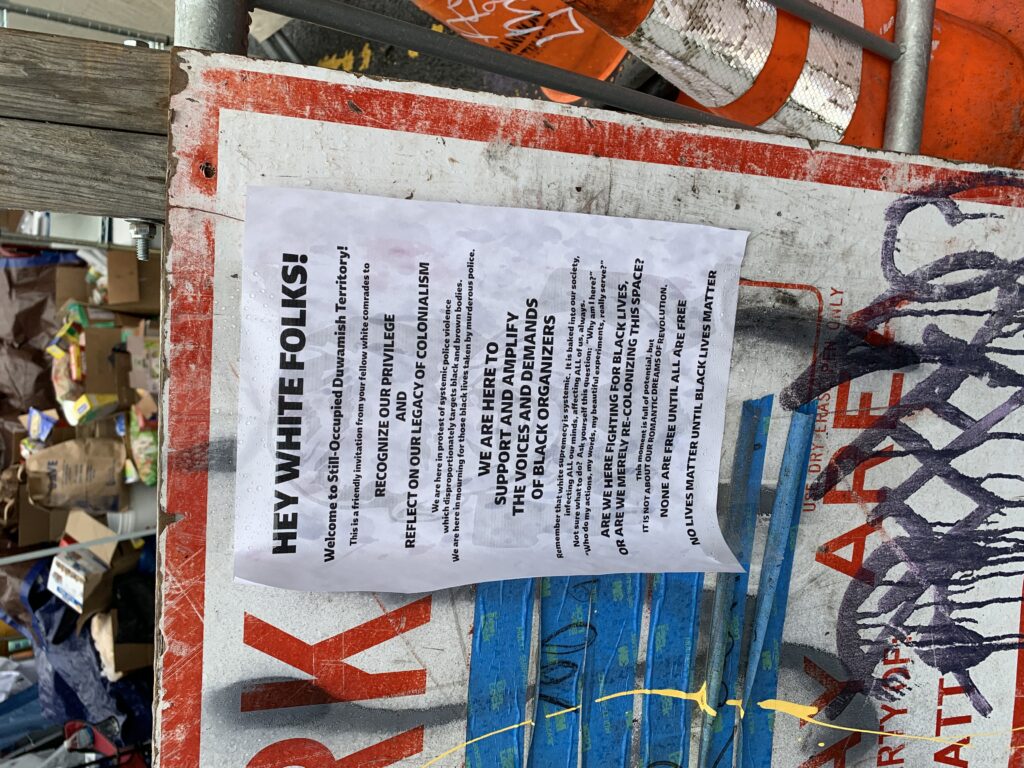

July 18 I went back for another look at the site of CHOP and found it was a large garden in Cal Anderson Park sponsored by Black Star Farmers. They have grown a lot of vegetables all with volunteer help. When I was there they were rinsing kale leaves to donate to a community kitchen for unhoused people.

In addition, there is a lot of historical information, homages to victims of police violence and reminders that we are on indigenous land.

Homage to George Washington Carver, original brilliant agriculturist at Tuskegee

Note Manuel Ellis sign on the right, he a focus in Naomi Ishisaka’s column today in the Seattle Times about how police reports can be fabricated.

This entry was posted on July 18, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

A Sunday Trip to the Olympic Sculpture Park

Taking a break from the heavy news and politics, we take an”expedition” every Sunday in Seattle. Last weekend we went to the Wooden Boat Center and went rowing. This Sunday we went to the Olympic Sculpture Park.

Here is Beverly Pepper’s Persephone Unbound. 1999. “The abstract language of form that I have chosen has become a new way to explore an interior life of feeling …I wish to make an object that has a powerful presence, but is at the same time inwardly turned, capable of self-absorption.” Beverly Pepper just died on February 5, 2020 in Todi Italy at the age of 97.

We haven’t been back to Sculpture Park for quite a long time, and it is stunning to see how much the vegetation has matured. Of course the art is almost all white modernists, but it looked great there, and it marks the extraordinary generosity of Seattle’s culture supporters. Hopefully SAM will be planning to diversify the artists as soon as possible, given the new awareness of the need to do that. There is one Latinx artist, Teresita Fernandez who created a glass bridge ( which is very hard to photograph), and all the signs included Lutshotseed and native practices.

The extraordinary accomplishment to take a derelict toxic waste site on a steep hillside that is crossed by a highway and a train track into an uplifting green space in the center of the city is to be honored. The museum literally moved mountains to create it. So here are a few images, just to inspire you to visit.

Richard Serra’s Wake 2004 This piece by Serra evokes giant ships going through the sea. It is of course overwhelming, but I certainly like this installation, compared to some of his work in public places. He has a working class background and grew up around a waterfront in San Francisco, where his father worked in a shipyard, so he has a connection to this subject. I met Serra years ago, when he installed a piece called One Ton Prop, House of Cards, at the Rhode Island School of Design, where I was part of the curatorial staff. It was traumatic because the House of Cards fell down, each “card” was 500 pounds!

Louise Nevelson’s Sky Landscape I 1976 – 83 sits in corner of the park with now a lush background. We really enjoyed this piece and thinking about Nevelson. She was such a distinctive presence in her later years with her triple false eyelashes. This piece is distinctly different from what she is mainly known for. But it is black. She says “I fell in love with black; it contained all color, it wasn’t a negation of color …blackis the most aristocratic color of all … you can be quiet and it contains the whole thing.”

Here is another work by Beverly Pepper Perre’s Ventaglio III 1967 from her earlier phase, more angular, but still provocative: she said “the idea is that from whatever angle you view it, the voids seem filled and the solids seem empty.

Mark Di Suvero Bunyan’s Chess 1965 “Unity and joy. That’s why I like to suspend elements from the beams of my works, so they can interact with the wind and other forces.” I love this work with its great chunks of wood. Di Suvero had an accident early in life and was disabled but never stopped making sculpture.

Alexander Calder Eagle 1971, the icon of the park needs no explanation.

The shoreline is intended to be a safe place for young salmon to grow up. I don’t know if that is successful or not. It apparently has an undrwater bence for near shore habitat. The pocket beach was created by means of excavation, driftwood, beach grass and pines.

Louise Bourgeois sculpture Father and Son 2004-2006 at the South end of the park is another iconic work as well as her chairs.

Of course, there is a lot more sculpture that I didn’t include here. I suggested to them to install the boxes from CHOP here! Wouldn’t that be a great change of pace. There is also the Vivarium by Mark Dion, which was closed. I always felt that they should have asked Buster Simpson to do a piece there instead. He has been doing sculpture that incorporates natural process for decades. And now of course there are lots of new approaches to public art. The pavillion that is a changing installation site for large projects was also closed. And we somehow missed the Anthony Caro! But it was a great Sunday.

This entry was posted on July 13, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

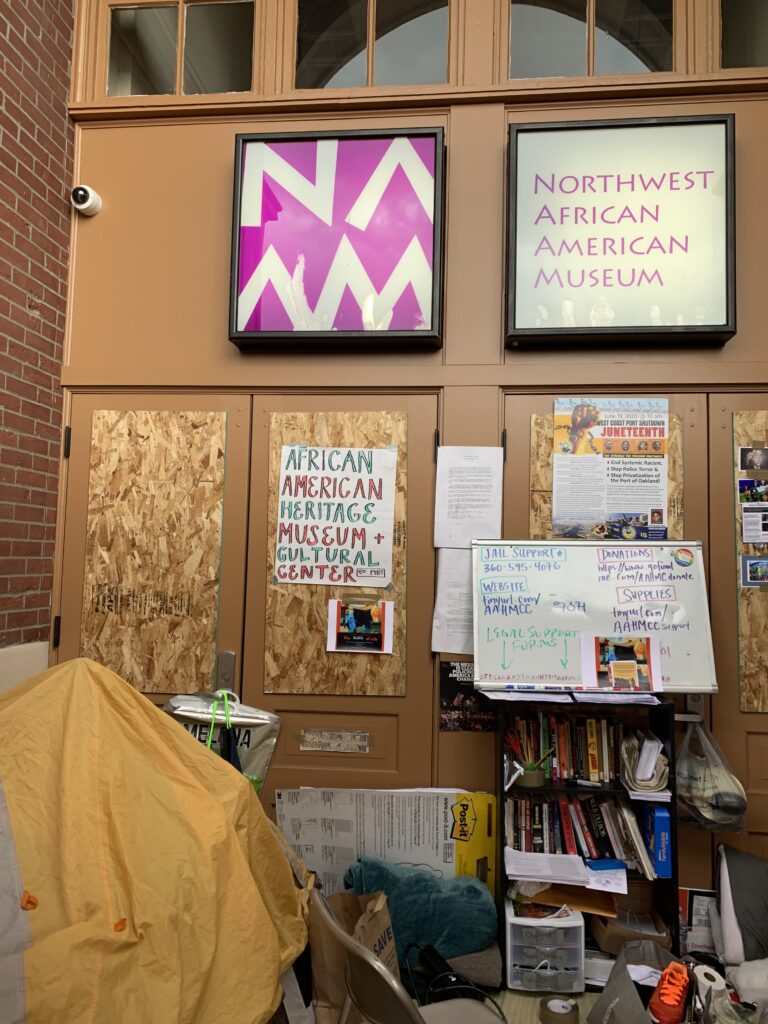

Occupying the Northwest African American Museum

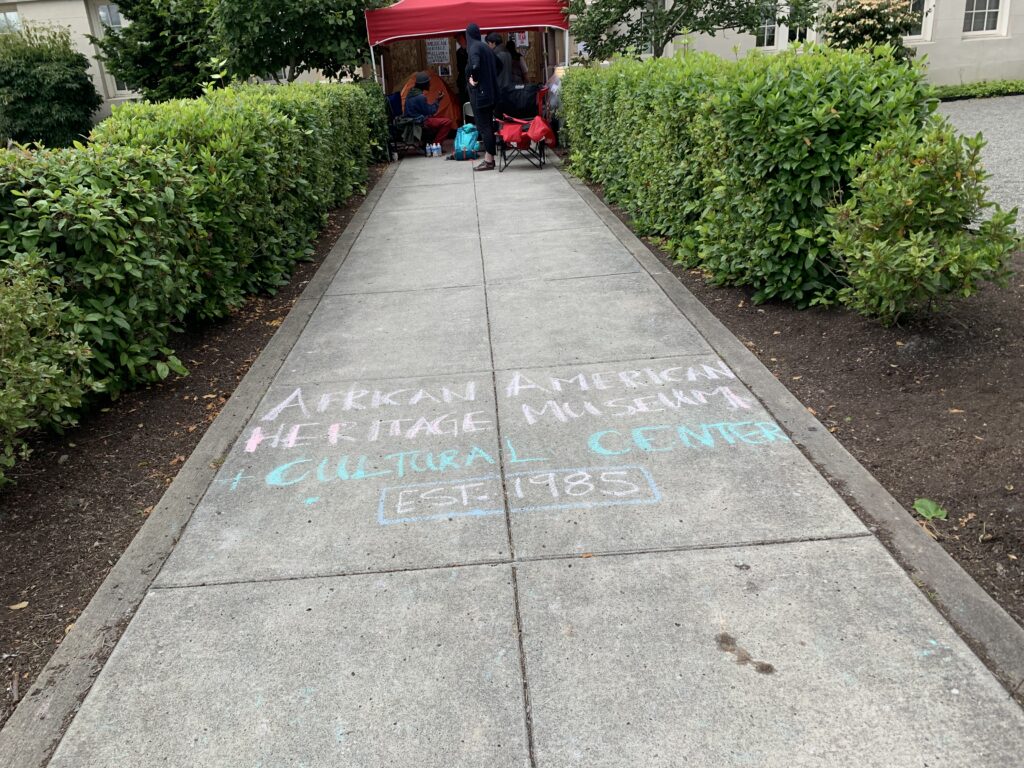

The Colman School, site of the Northwest African American Museum, has been occupied since Juneteenth by Omari Tahir, Earl Debnam, and others to declare that they are the rightful owners of the property based on a purchase agreement and loan agreement from January 1998, a copy of which they provided to me. Tahir and Debnam were involved in the original occupation in the 1980s and 1990s.

They state that they are the “real museum” with the name of African American Heritage Museum and Cultural Center. They have a report from the Mayor in 1994, that was Norm Rice, outlining the programs for the museum that included a visual arts center, musical center, artist in residence program, intimate performing/workshop space, practice space, instrument library, and a recording studio.

They state that the current museum does not fulfill these intentions and it is not “supporting the community.” They occupied the school for amazing 13 years between 1985 and 1998 during which they created an exhibition of displays of African artifacts that Omari brought from Africa, they “led workshops, held concerts, engaged with youth to be proud of their heritage so they would not turn to the streets.” That was a huge motivation for both their original occupation and their current occupation: as shootings of black youth continue to escalate, their desire to connect to youth through African heritage is remotivating them to continue their campaign.

So what happened to their plan? You may recall that Omari’s son, Wyking, then identified as Kwame, staged an intervention at the opening of the museum to call attention to this project. Apparently the original board had members who opposed the African American and Heritage Museum and Cultural Center as conceived by the occupiers. The group were evicted and all the displays were taken away and never reappeared. Then the building was sold to the Urban League, in spite of the purchase agreement that had been signed.

After many more years, the current Northwest African American Museum opened. I asked the occupiers what the NWAAM response to the occupation had been. The chair of the board called the police to evict them three times, but the program director has, according to their account, been more amenable to listening.

Clearly some new programming is not enough to satisfy the occupiers, but it seems to me to be a starting point as a resolution. Personally, I find that the NWAAM is a positive presence in our community. Their focus has not been music, which is clearly an aspect of the lack of connection to the community in the opinion of the occupiers, ( 5 of 7 parts of their original program concern music). As far as other parts, like a Visual Arts Center, their complaint is the absence of a connection to Africa. But of course we do have the fantastic Seattle Art Museum collection and curator. An artist in residence program is a great idea if they get the funding. The James W. Washington House had an an artist in residence program that was incredibly successful while the funding and direction lasted.

So I am going to simply report on this important event. It needs to be covered, there has been no press on it at all. Underlying the issues here is class conflict, between elites and ordinary people as well as between middle class liberals and radical left politics ( Omari participated in the occupation of Centro de la Raza and Discovery Park with Bernie Whitebear and the Gang of Four). Also there is the legal issue based on the purchase from 1998, that was prevented from being completed.

Museums all over the country are hopefully examining their elitism right now. Black Lives Matter certainly has opened up awareness that ALL museums suffer from elitism, whitism, and lack of connection to ideas for connecting to community in a way that can address mitigating violence, gangs, and drugs in the streets. If Police departments were defunded to provide more money for community, this is one direction it could go.

My good friend Georgia McDade sent me an article outlining how black creatives perform for white audiences, white cultural power structures. That is definitely something to think about here. Is NWAAM partipating in that? I don’t think so. In fact the white power structure of Seattle’s cultural community has not embraced the museum and its programs as anyone can see if you attend a program there. The same is true of the Wing Luke Museum in the International District. Segregation is alive and well in Seattle culture, even as the Central District fights for its identity as a center of black culture in the midst of rapid gentrification. Africatown is resisting this process. So are these occupiers, ironically, as they protest the “gentrified” NWAAM departing from their vision.

This entry was posted on July 7, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

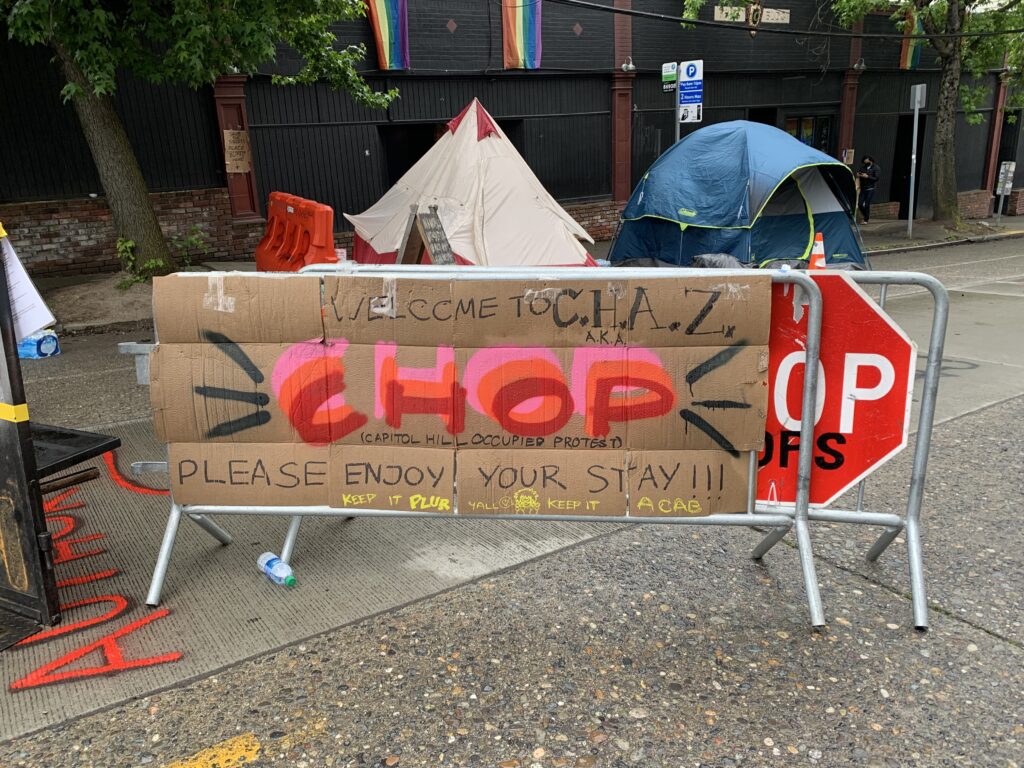

Capitol Hill Organized Protest

Capitol Hill Occupied ( now called Organized) Protest is evolving as I write, so this is simply a report that will have to be updated. Everyone heard about the tear gas confrontation from Sunday June 6-7 and the departure of the police from 10th precinct, the “zone” as it was called then. I went down there twice on June 12 and June 17 to document mainly the visual aspect of the protest. While I was there on June 12 I was fortunate to witness an interview between Omari Salisbury and TraeAnna Holiday on what was happening there, what the principles of the protest were, as well as their goals (demands). Omari has been on the ground with his Converge Media since May 29 reporting day by day developments. The link is his morning update show. Here I got caught on camera during the show on June 12. That’s TraeAnna Holiday speaking on the mike.

TraeAnna and Omari were talking about offering an alternative to the news bites of sensationalist mainstream media as citizen journalists. ( All most people know about this protest is the tear gas on the first night).

TraeAnna is an activist as well as host of the morning show on Converge She is a community organizer for the Africatown Community Land Trust that “empowers Black residence by fostering land ownership.” Her emphasis is on the hope for equity and coalition of the like-minded to dismantle the racist system. She spoke of resilience, peace, and community as the guiding principles as well as a community based process for transferring property.

Omari has captured the critical moments in the day to day events there, most dramatically, and featured on Democracy Now, when the police simply left the precinct.

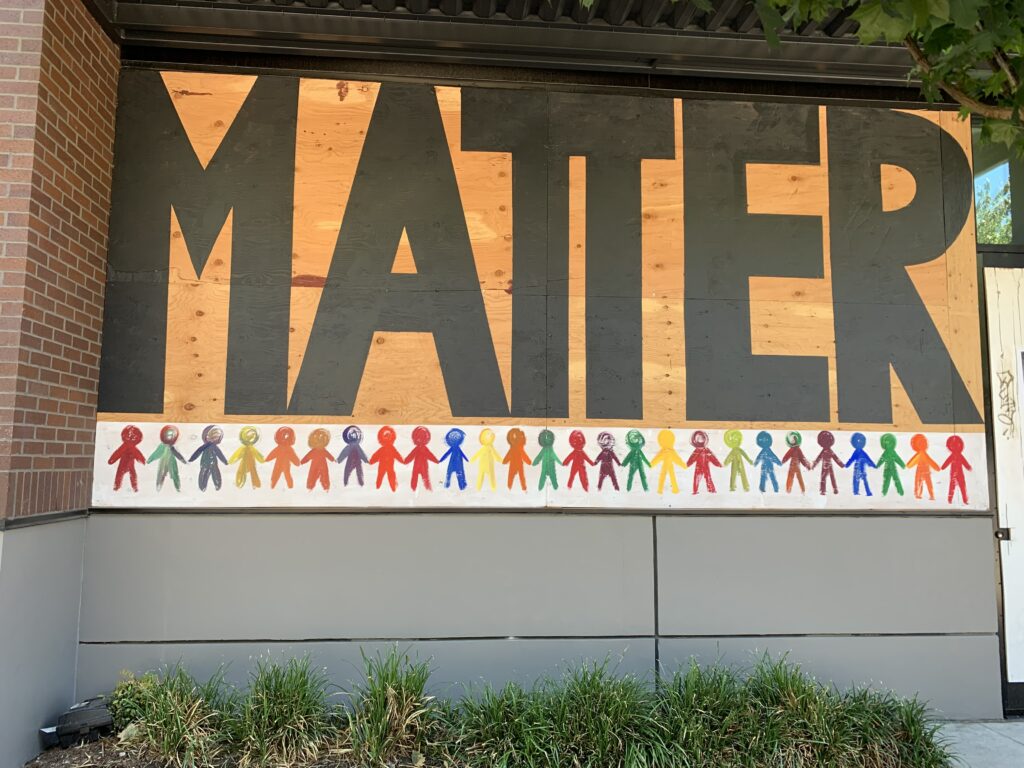

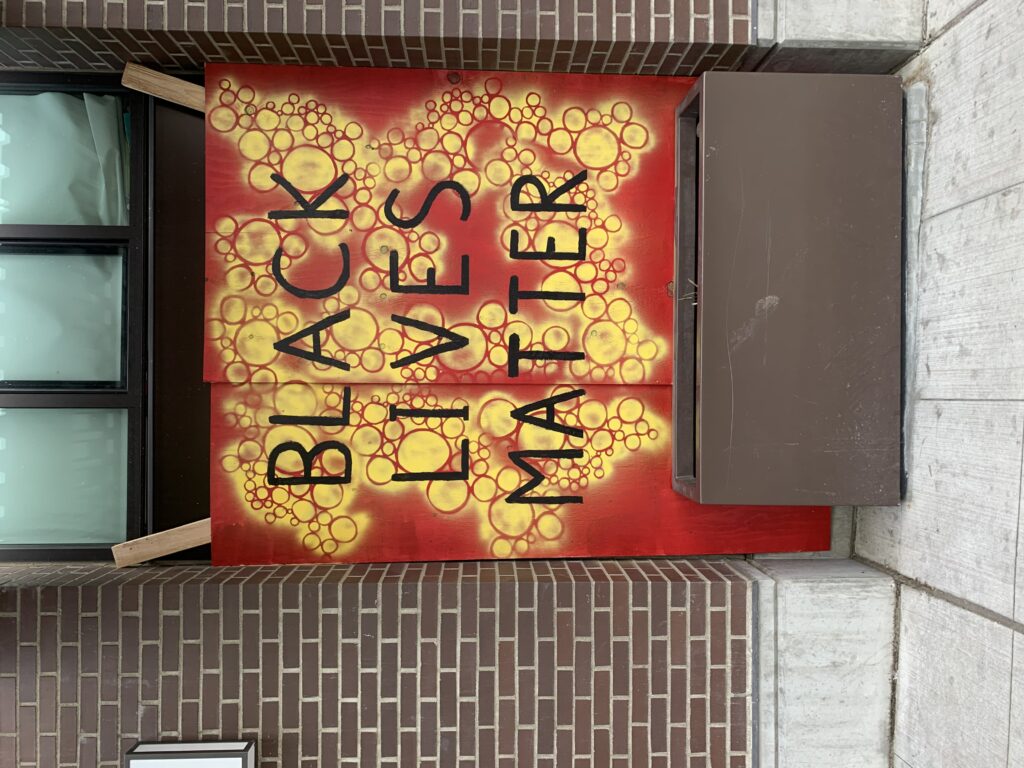

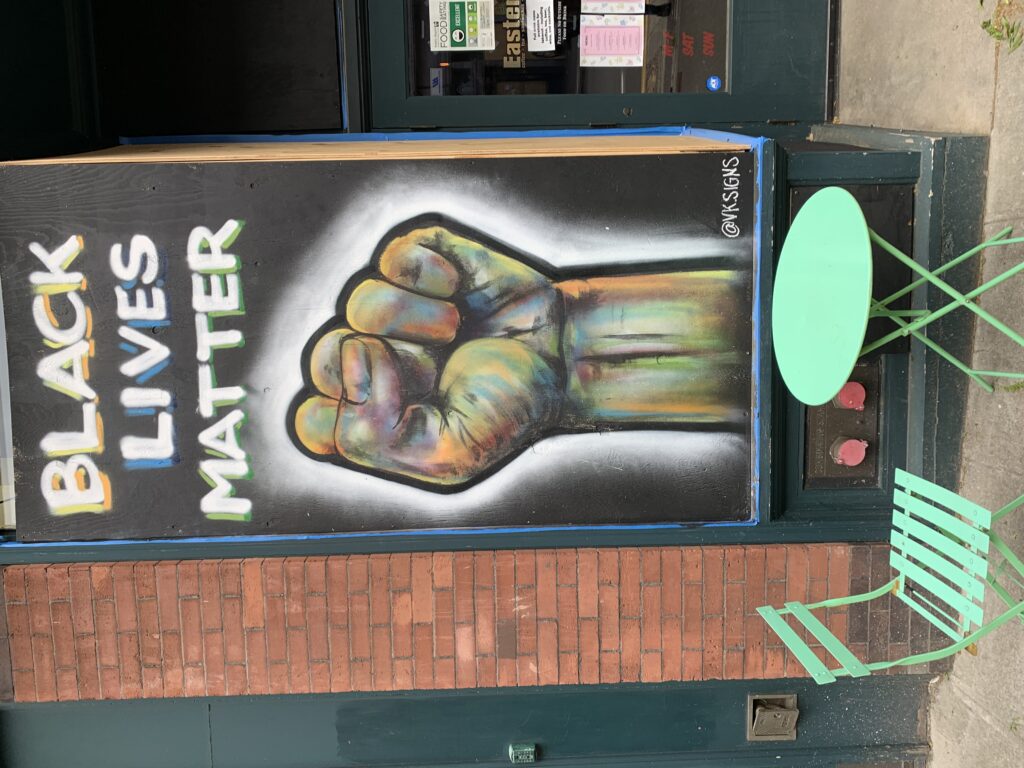

So what do you see if you go there? Here are some images on the street, a giant Black Lives Matter mural: each letter painted by a different artist with photos by my partner Henry Matthews.

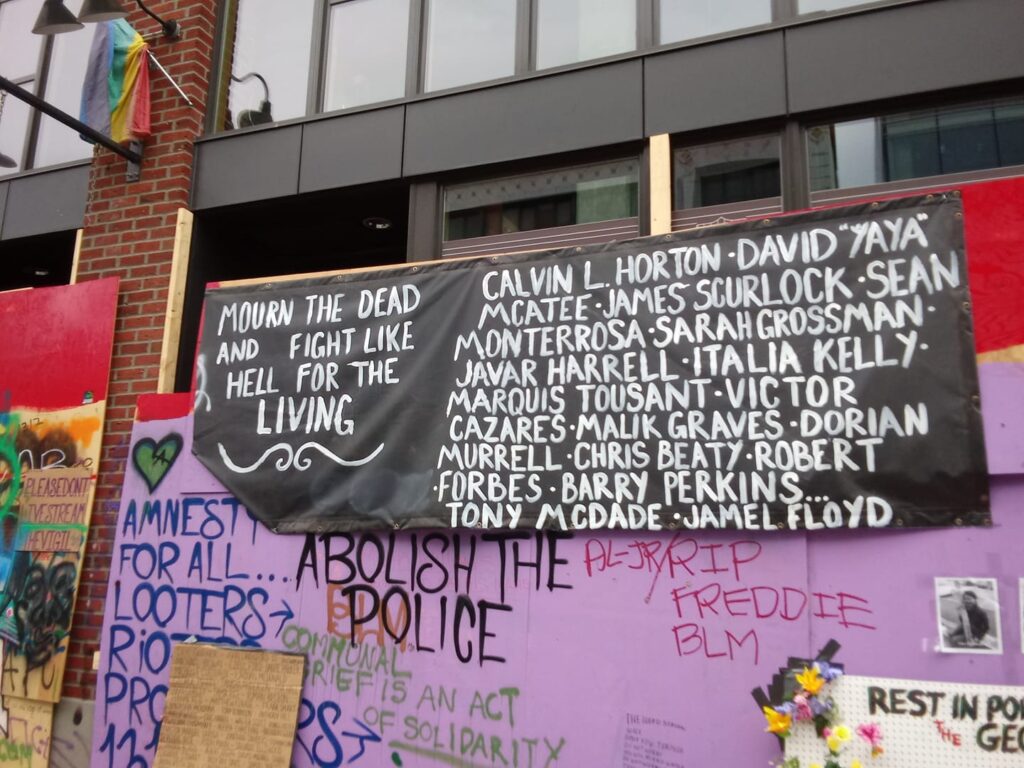

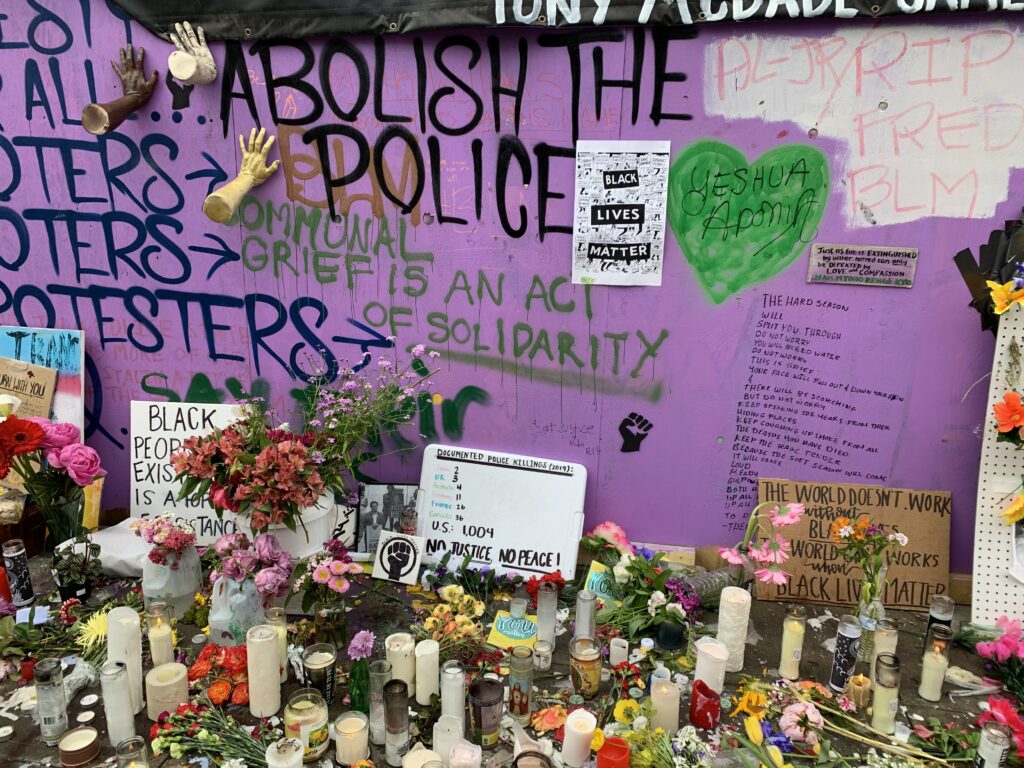

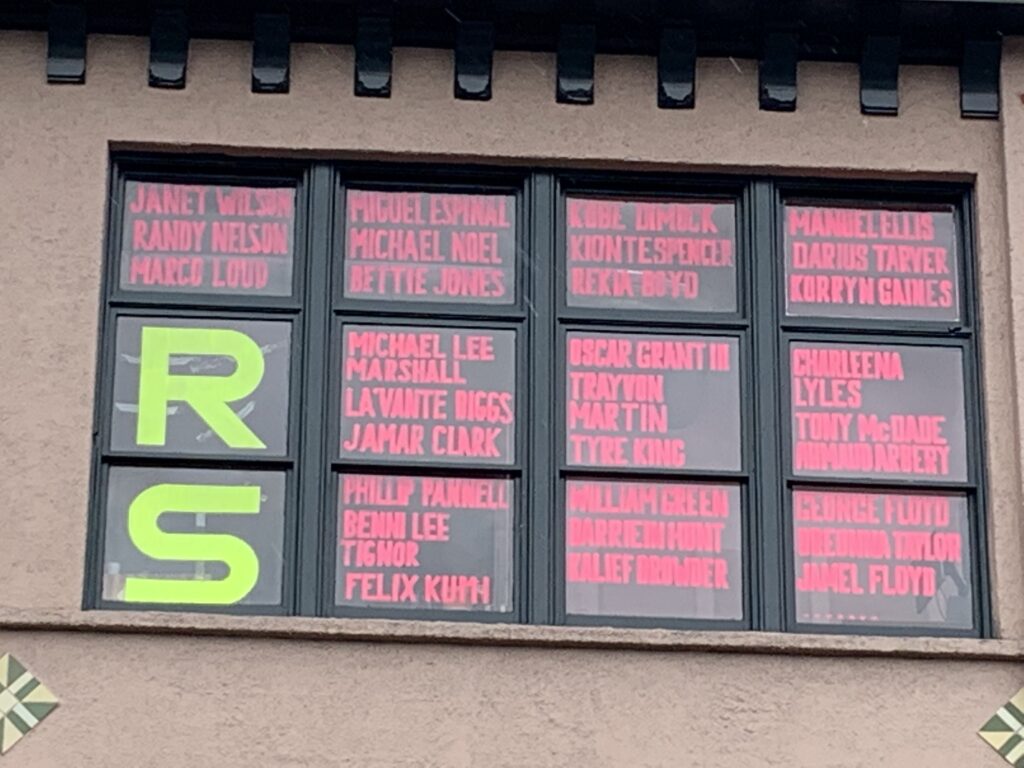

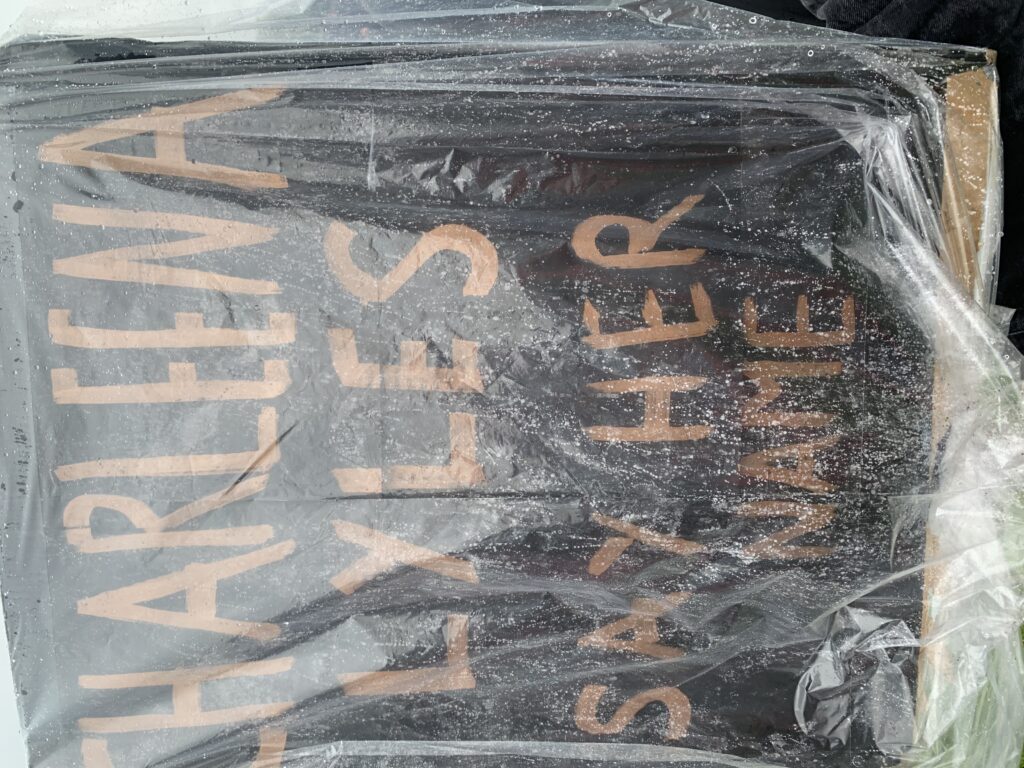

This is the most formidable accomplishment, but there is art everywhere. The second most impressive work is the monument to those who died by police violence.

This is the longest list I have seen, although oddly it leaves out Charleena Lyles who died in Seattle. Here is a separate monument to her that I posted on my previous blog on the marches. I listed the names and ages of all the people listed below there. Here they are again. I feel it is important to name their names as often as possible. Yesterday I heard a wonderful poem that took each name as a poetic verse : George FLoyd age 46, Breanna Taylor age 26, Ahmad Aubrey, 25 Eric Garner 43,Michael Brown 18, Tamir Rice 12, Freddie Gray 25, Philando Castille 32, Stephen Clark 25, Trayvon Martin 17, Manuelle Ellis 33, Charlene Lyles 30

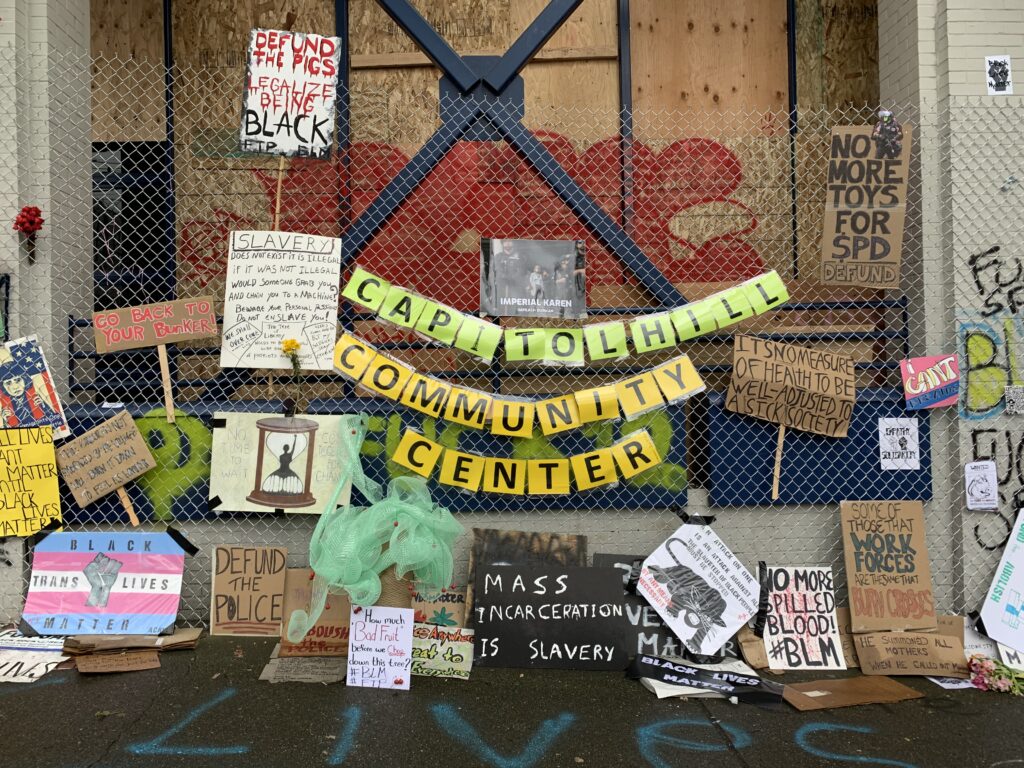

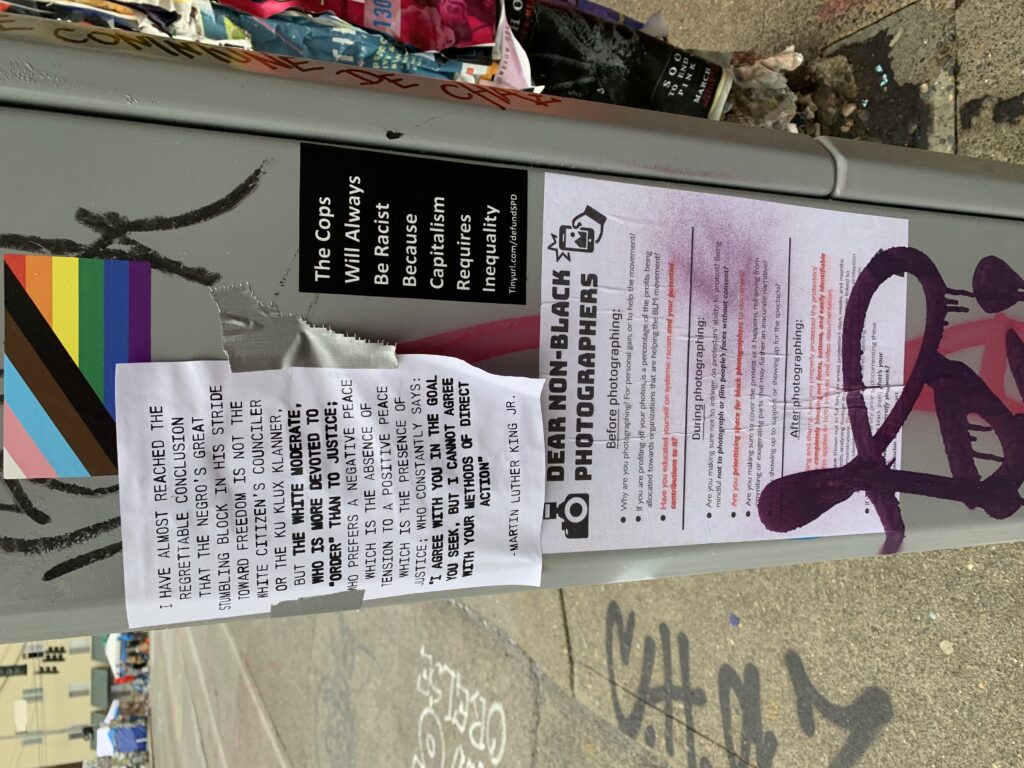

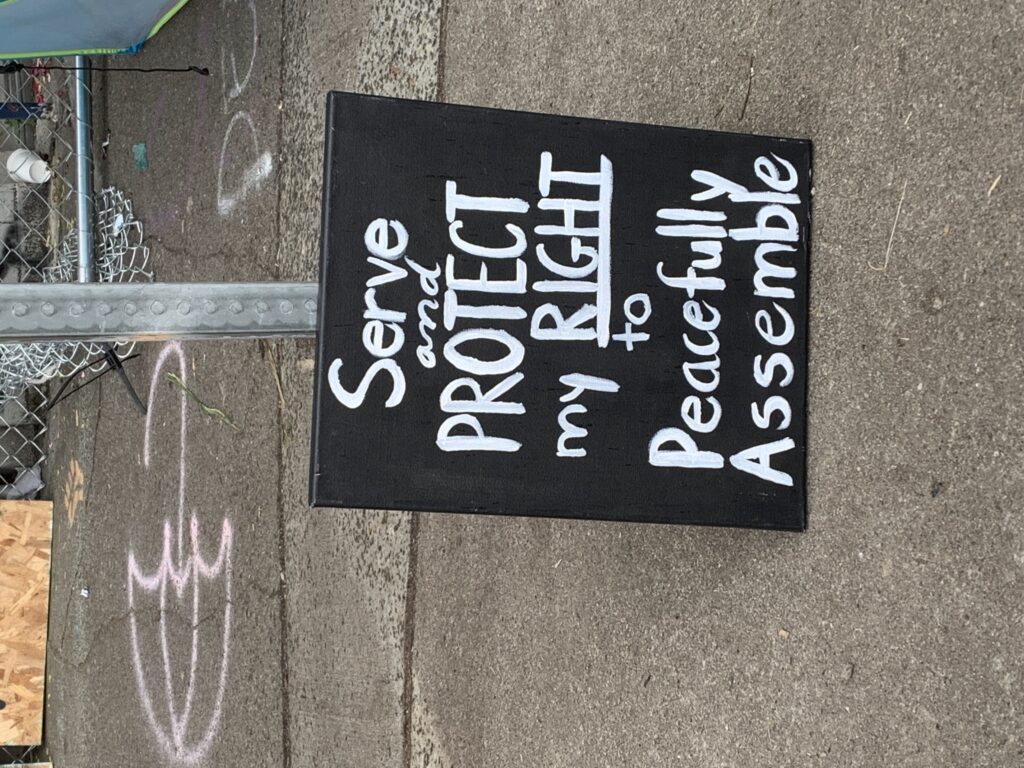

So now we will go back to where the street was blocked on 12th and Pine (the barricade is no longer there, it was removed by a nearby resident)

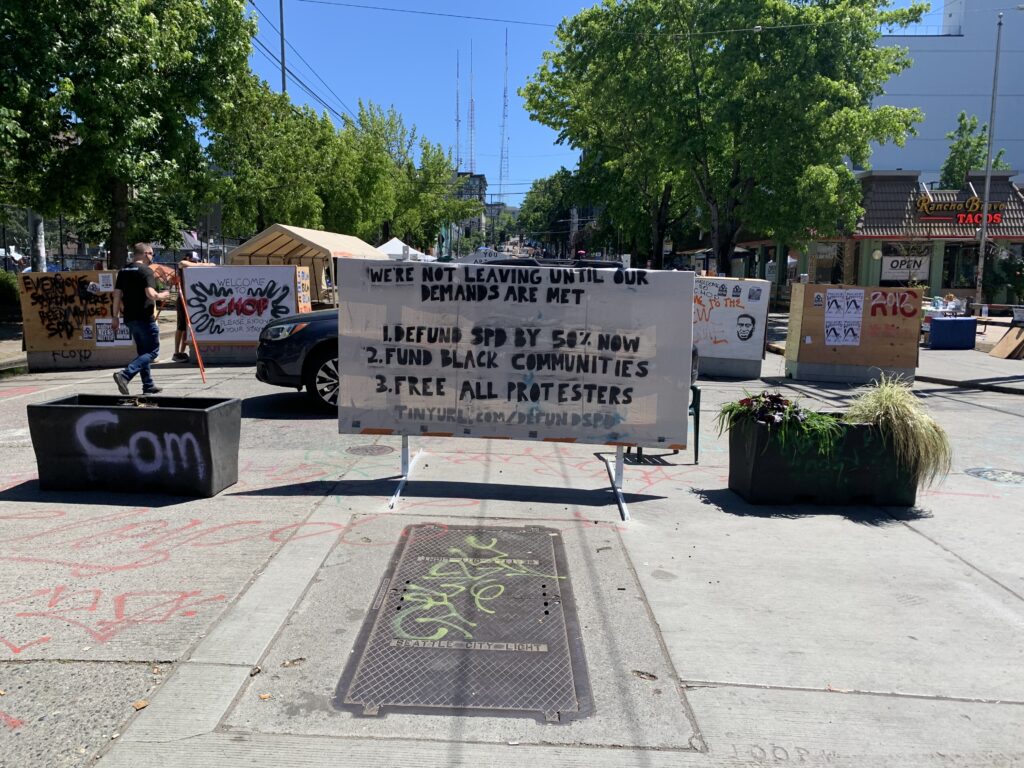

This is what the corner with the police precinct looked like on June 12 and a few days later. Around the corner were the demands on the plywood

1 Defund the Police by 50 per cent 2 Fund Community Restorative Justice, Housing, Healthcare 3 Freedom for all Protestors.

Note the three planter boxes and the pile of dirt in the foreground. Planting gardens is part of the activity. Here is a view of what Omari calls the “chill” zone on the North side of Cal Anderson Park with more planters.

Speaking of food here is the No Cop CO-OP with lots of donated food from local bakeries and restaurants

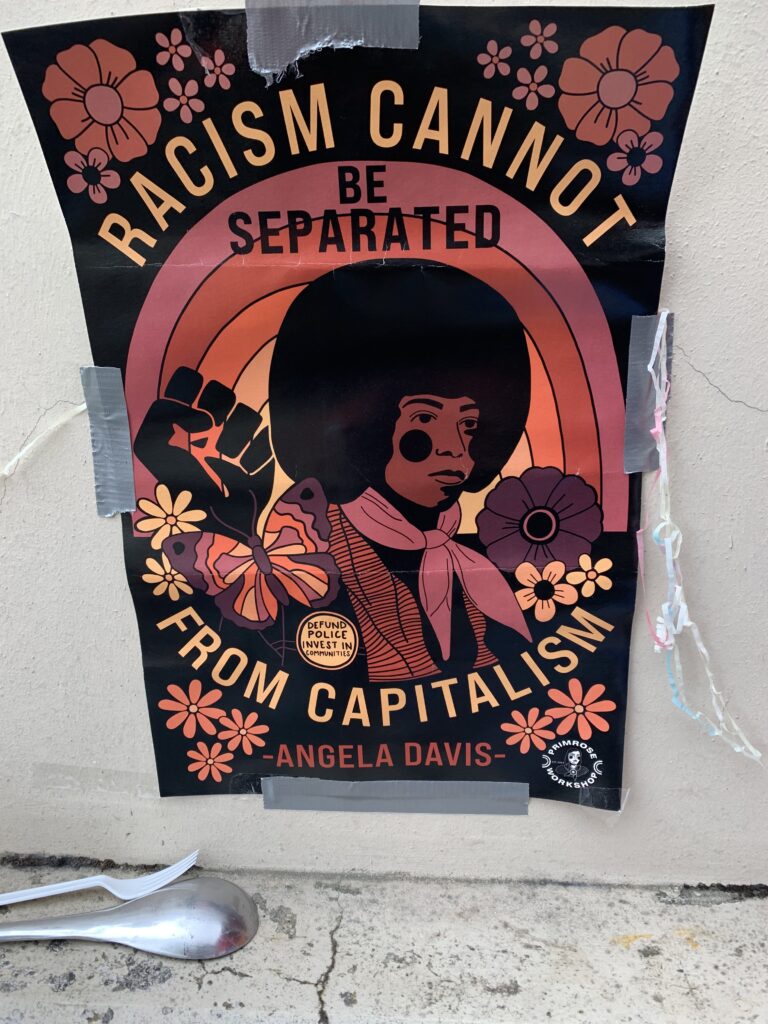

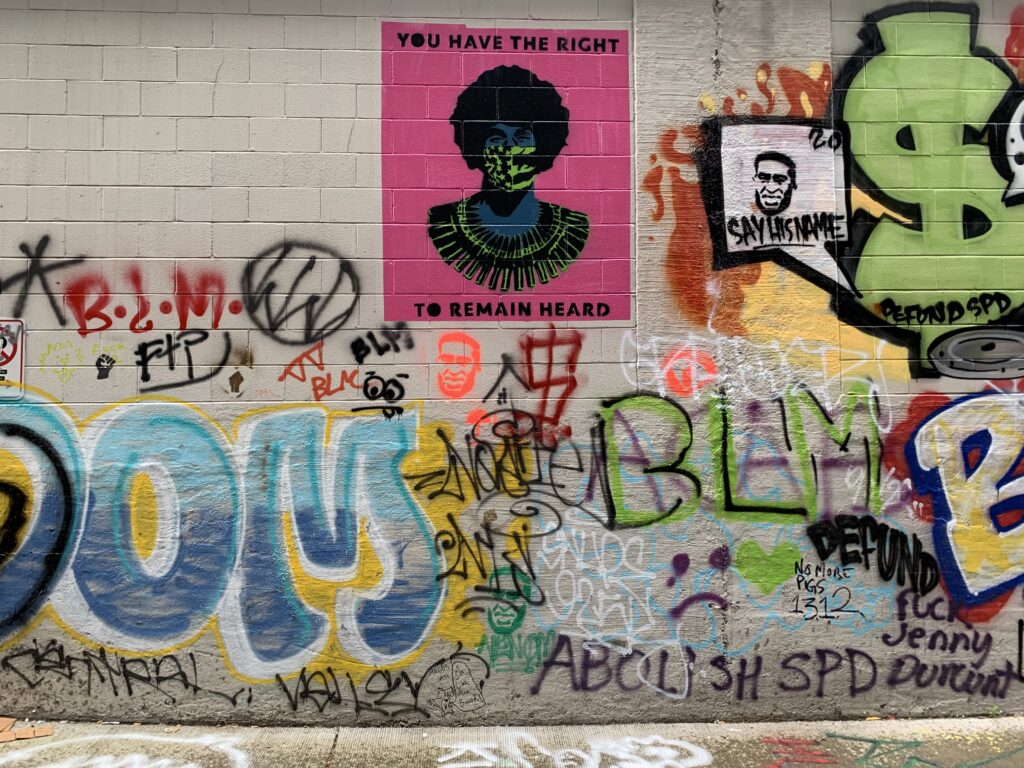

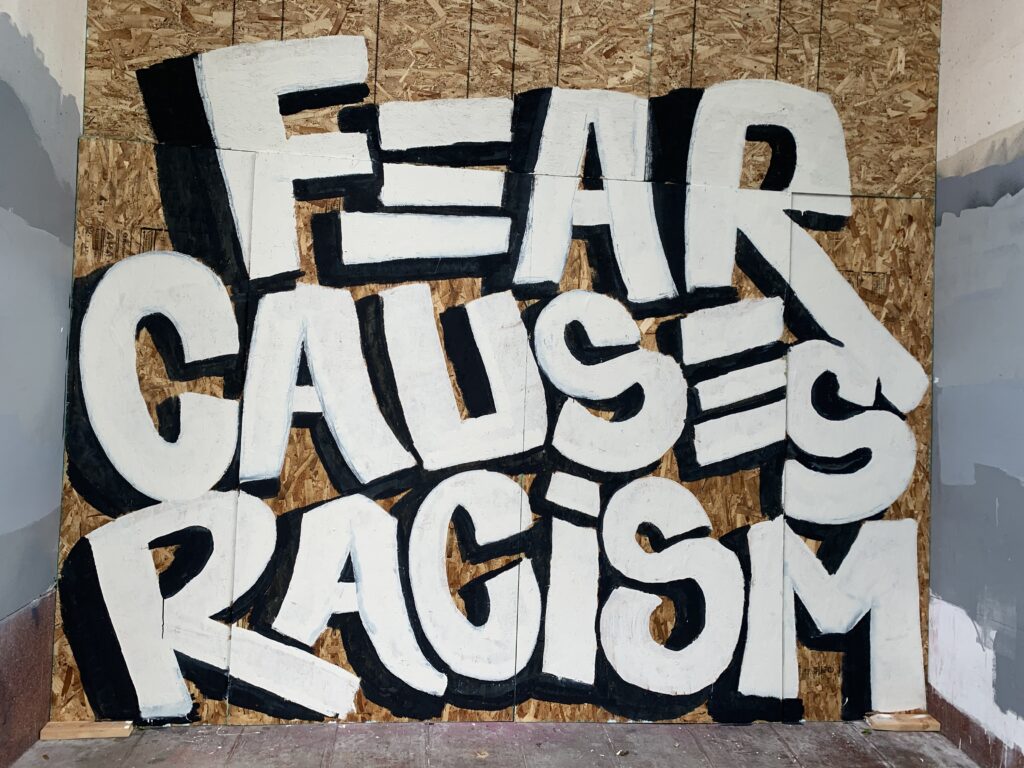

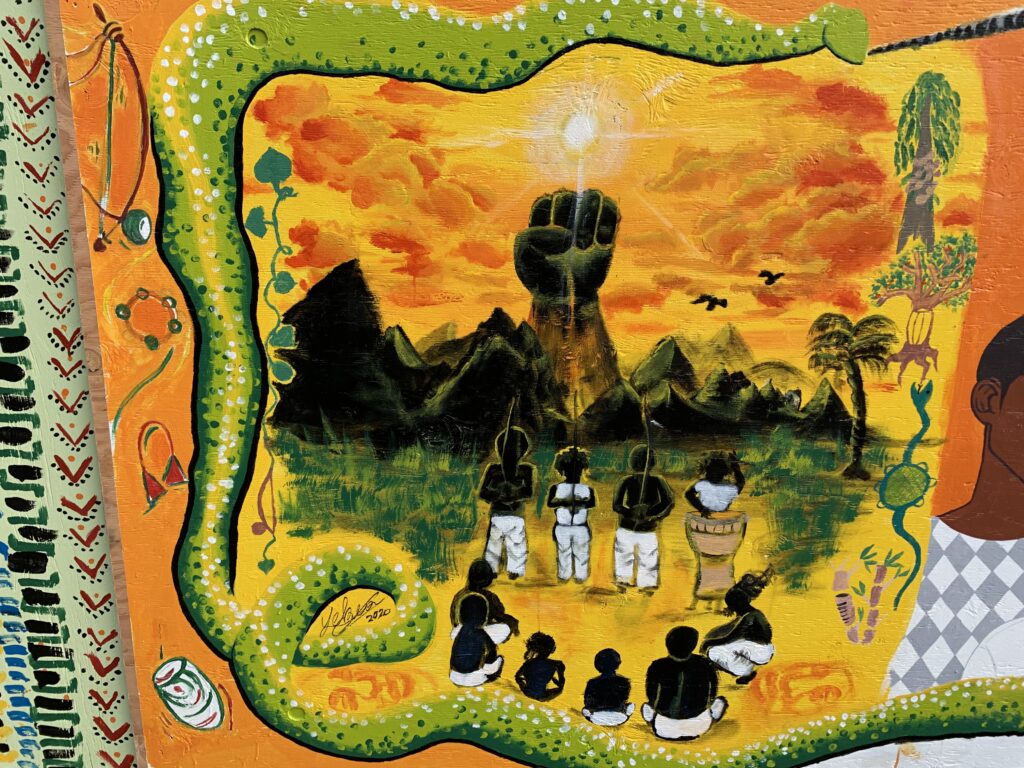

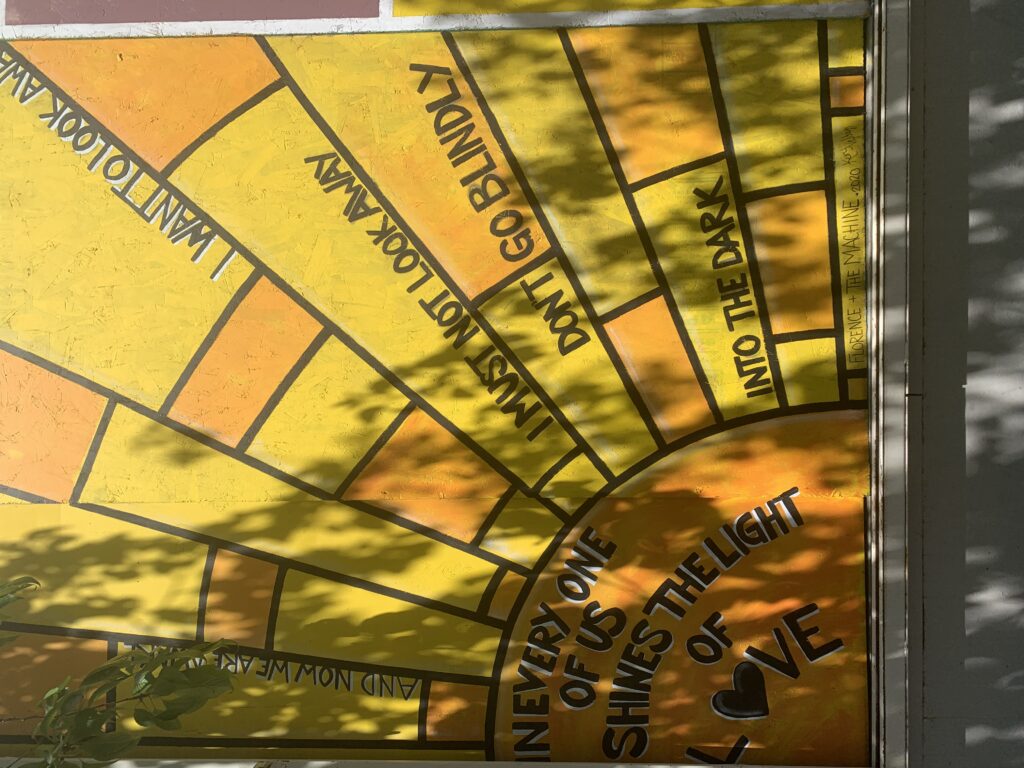

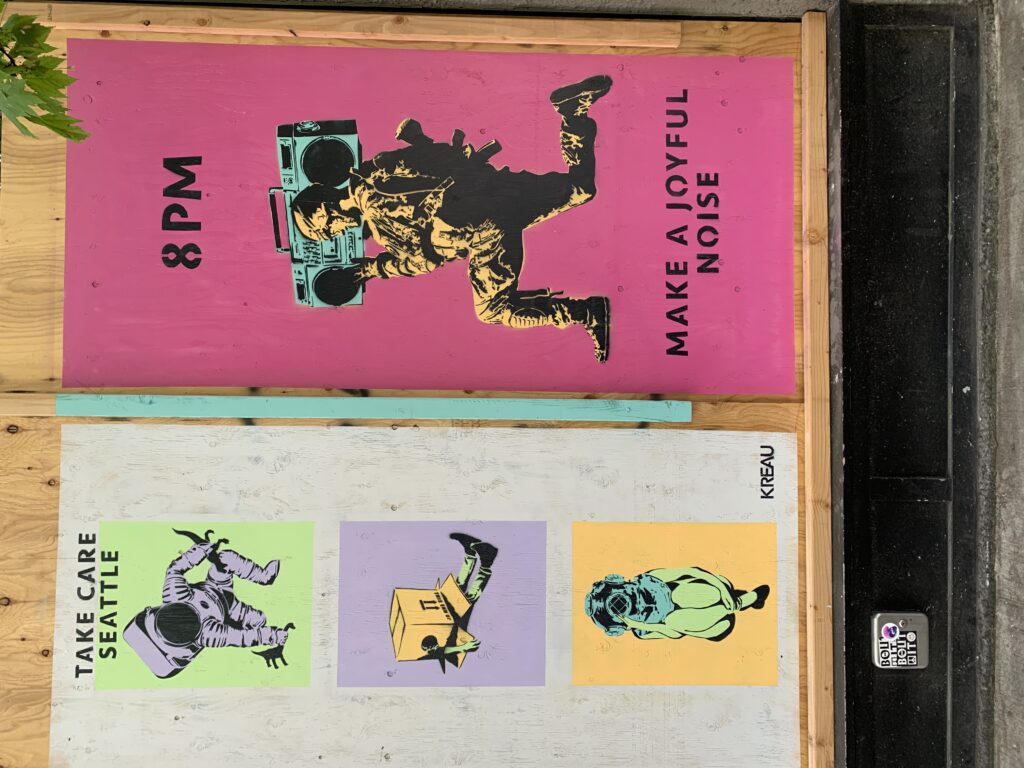

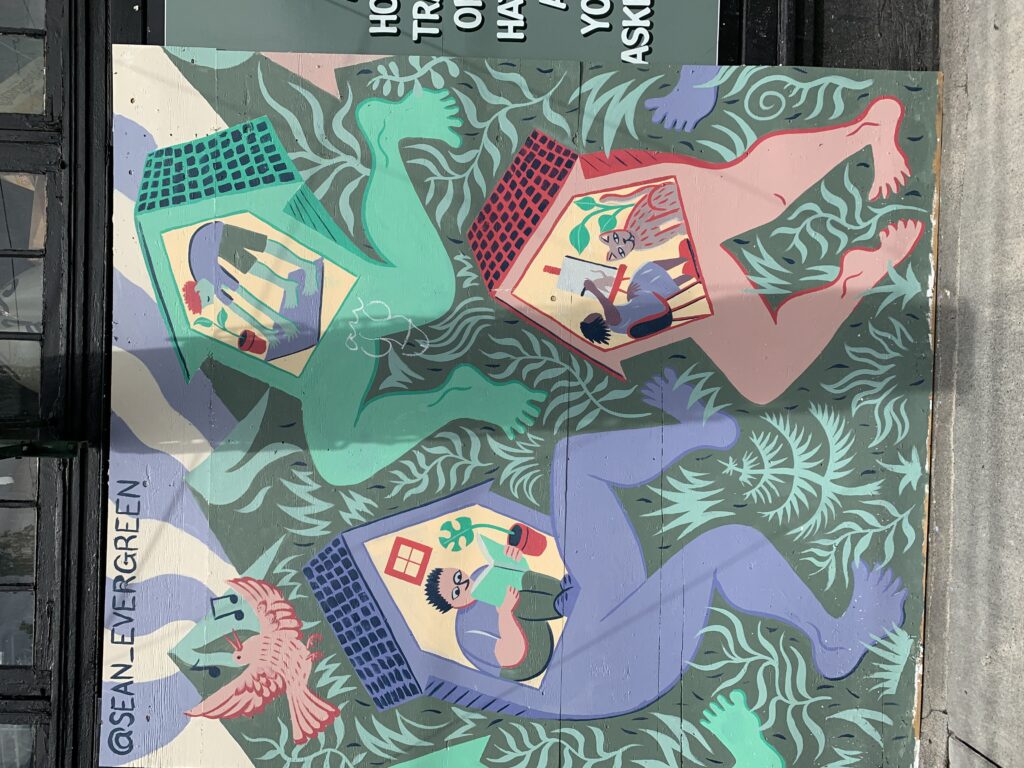

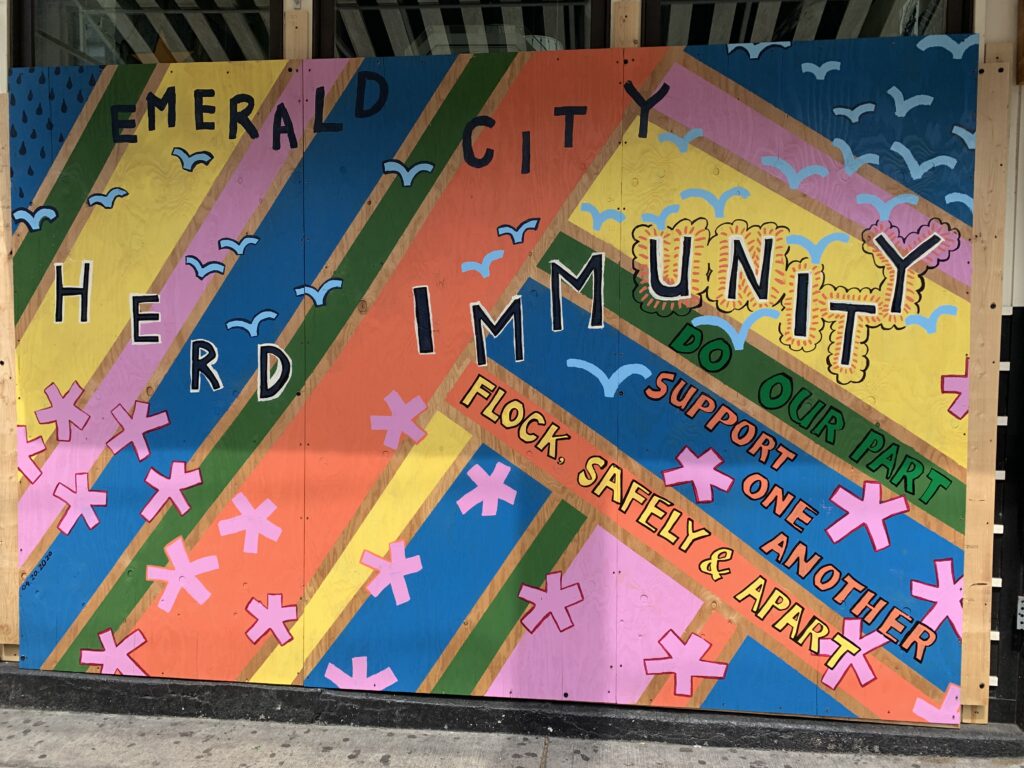

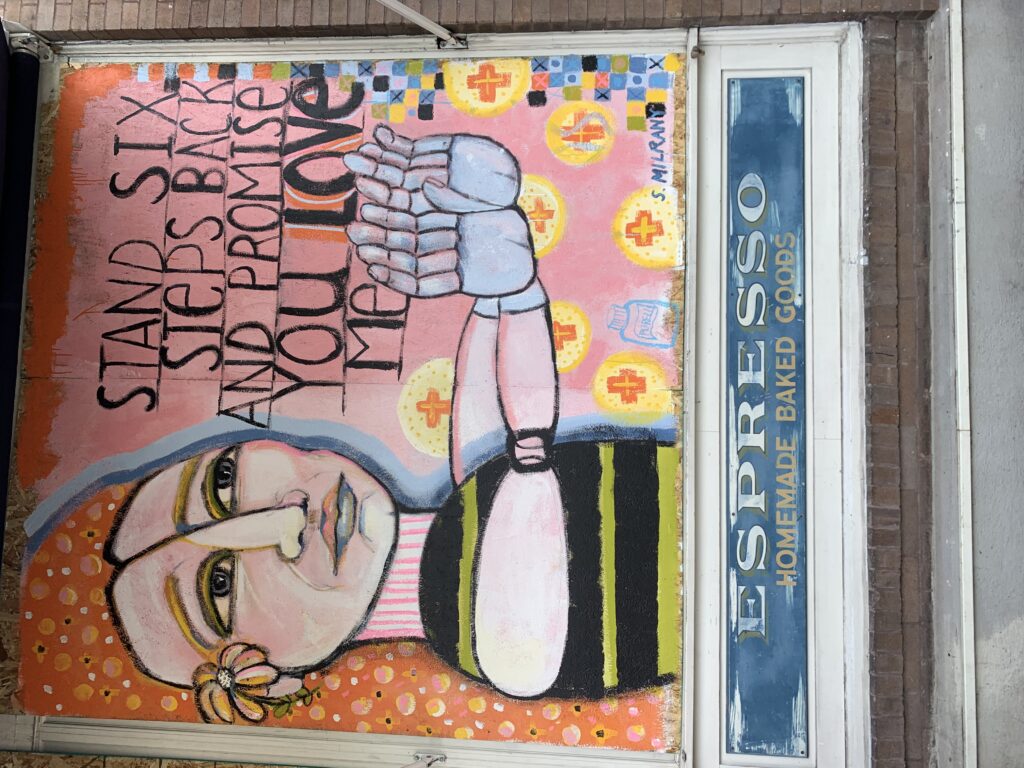

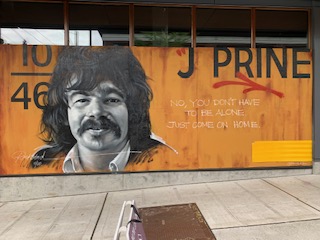

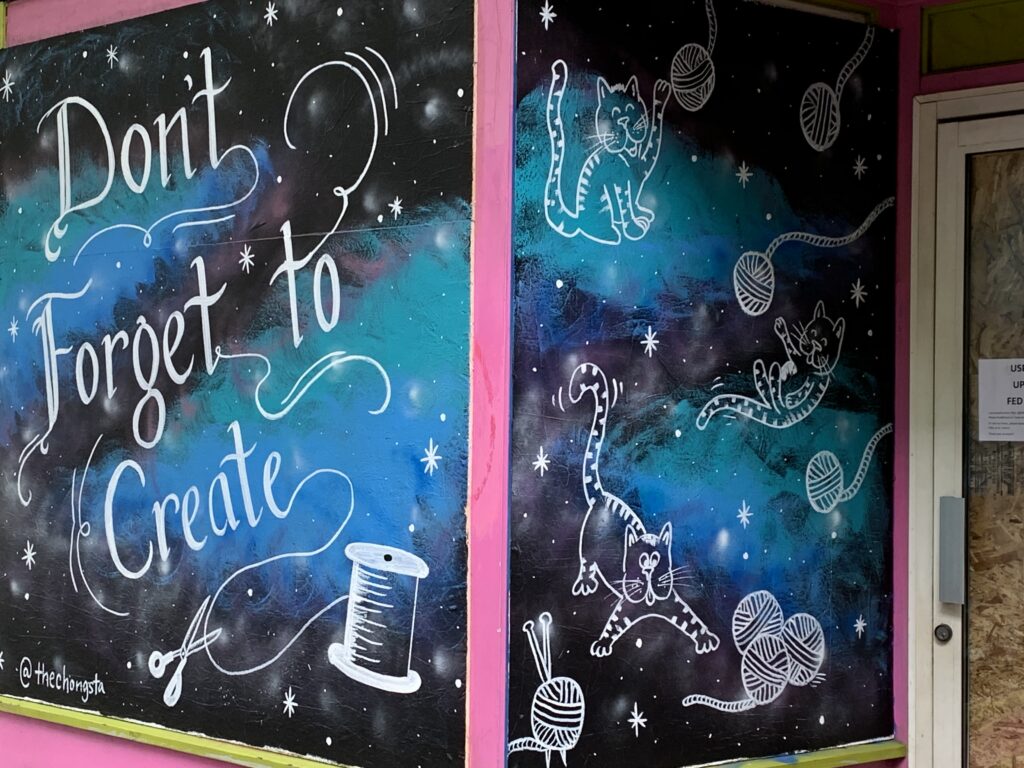

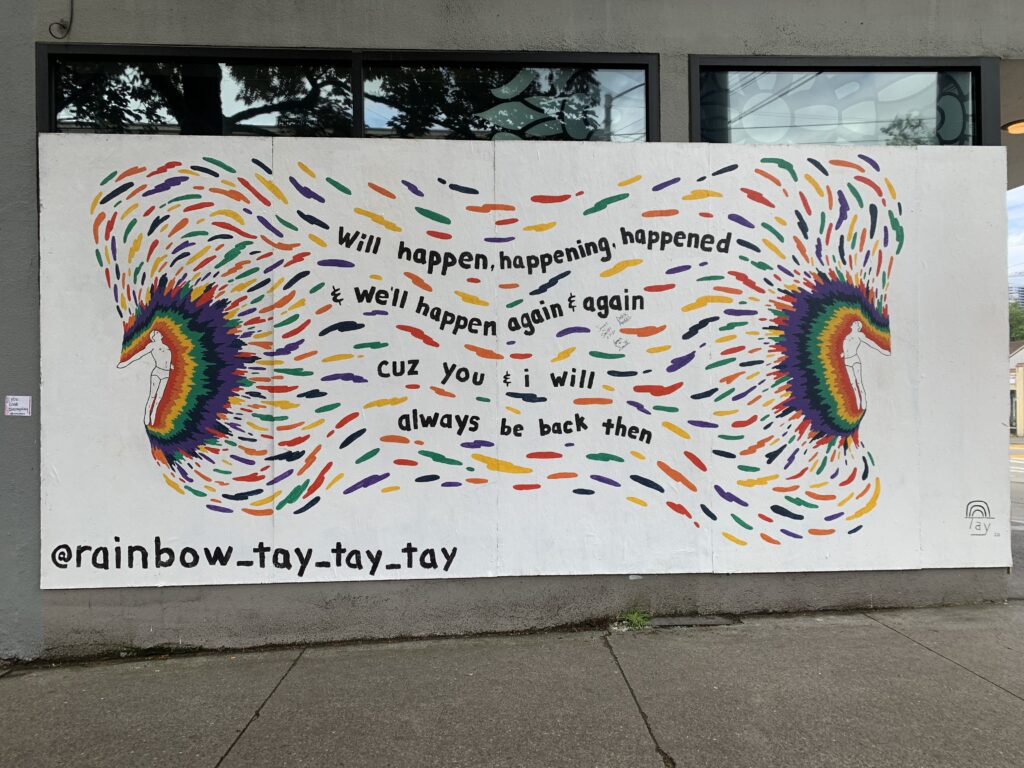

And then there are the many protest murals everywhere

I was happy to see this connection to the Gezi uprising in Turkey and the call for freeing Demirtas. Selahattin Demirtaş is a Turkish politician of Zaza Kurdish descent, member of the parliament of Turkey since 2007. He was co-leader of the left-wing pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party, serving alongside Figen Yüksekdağ from 2014 to 2018. He has been imprisoned since November 2016.

Hugo House is a writers center across the street from the encampment. It used to be an old house here, now it is the first floor of an upscale apartment building.

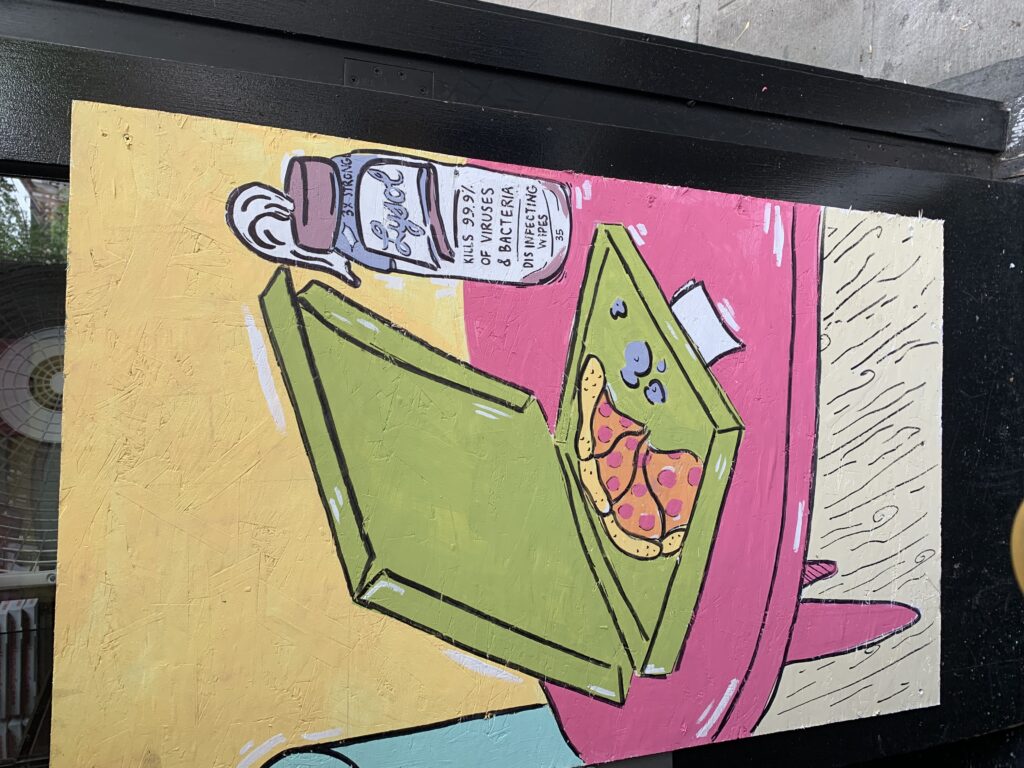

Then there are the COVID 19 murals I documented in a previous post which have now been graffittied. The artist with green hair here was showing her work. I pointed out to her that she perfectly matched the colors in the mural including the new message.

See below for another update of this mural site on June 22. .

This is an evolving situation as I write. I will add an update once I get the final information about what happened today. Tragically two people were shot. One of them died. I think this is the beginning of the end of the CHOP. Very sad.

Part II

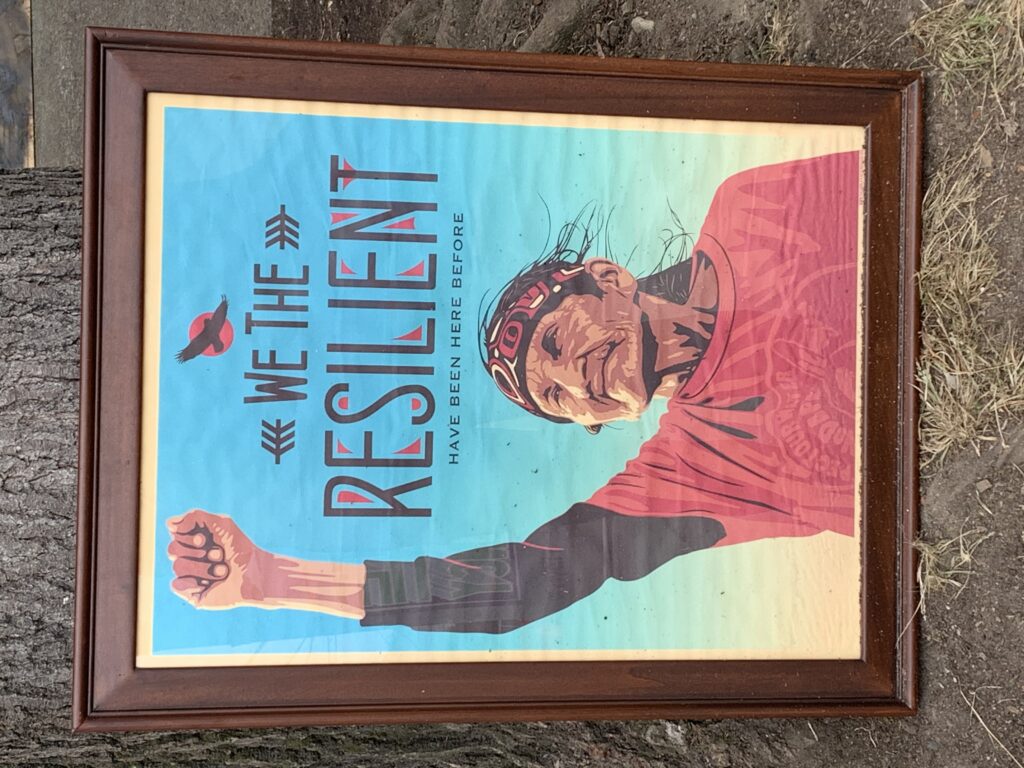

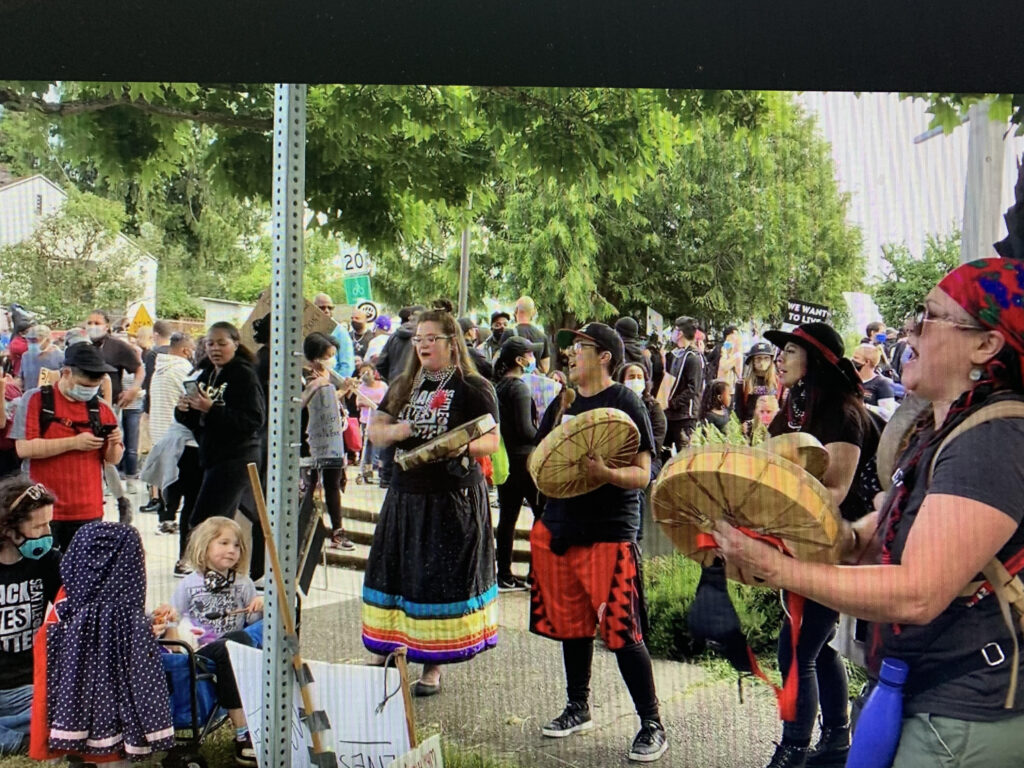

I went back today June 22. We were in search of a totem pole we read about in the Seattle Times,but no one knew anything about it. John T. Williams was a native carver killed by the police in 2010. ( That’s a link to my blogpost about it). His grandson was creating a totem for the CHOP zone according to a photo from the Seattle Times, but it has also vanished from the newspaper! There was a native drum circle in support of CHOP which I didn’t see, so I will add a photo of a BLM Native Drum circle from my first march, see post above.

The mood now is entirely different. I am still depressed by it. The spirit of the confrontation seemed more dispersed, less clear about the purpose of the protest, less protest, more sort of people hanging out and a huge amount of graffitti. But there were more people. There are for sure, more tents. Some BLM people feel this occupation has diverted attention from the main issue, but here it is, front and center, another young black man killed.

The site of the shooting of the young man, Horace Lorenzo Anderson, Jr. had a memorial right in front of the COVID 19 mural that I have documented as it was first installed and its earlier graffiti ( above). Now it has a whole new layer of graffiti. I am not sure this was the actual site of the shooting as it took place outside the CHOP. And Lorenzo was not part of the CHOP either. We still don’t know who the shooter was and there was another shooting last night. Lorenzo had just completed his diploma the day before. Apparently Lorenzo was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, code for a gang confrontation, but he was not part of a gang according to his family.

I will take you through our walk from Broadway and Pine around Cal Anderson Field. The graffitti feels angrier, less skilled, and generally it was defacing everything, rather than suggesting a concentrated political message.

This was clear, but perhaps unrealistic. It is impossible to defund the police by 50 percent over night. “Defund the police” was the former cry and it is crucial to do that! But the process is going to be difficult. Mayor Durkan said she didn’t want to reduce “her officers”. We need to keep on with the pressure, but maybe this street occupation is not the most effective way to achieve the goal.

“Cops aren’t workers” ? Not sure who created this slogan.

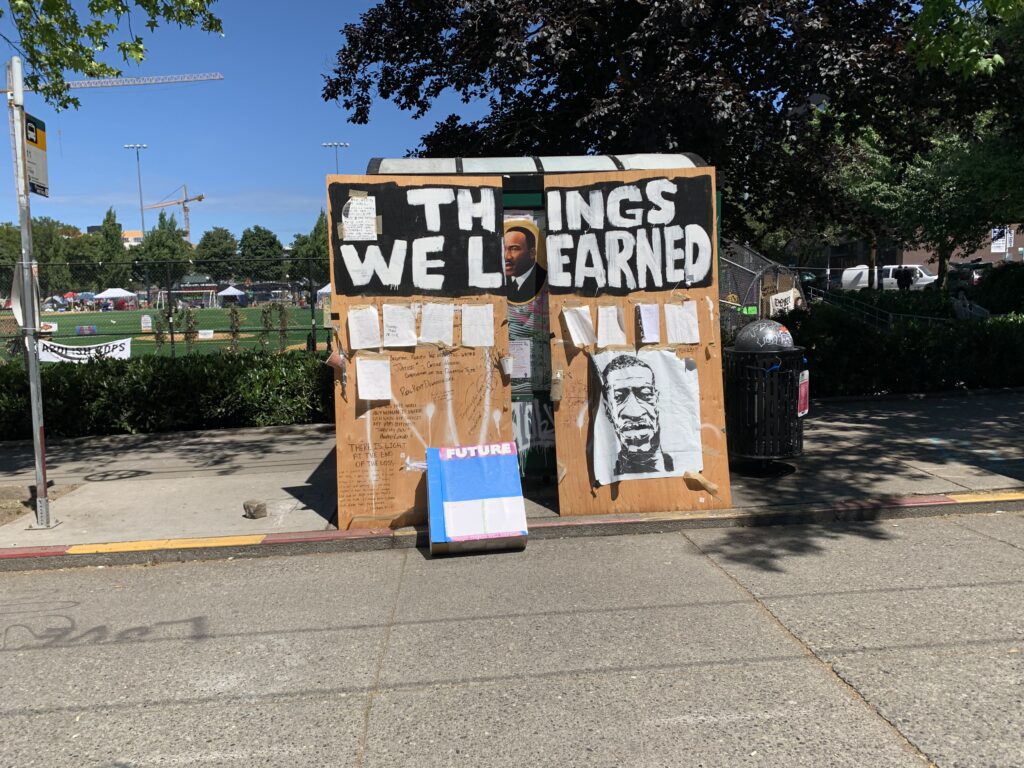

You can see the beginning of the giant Black Lives Matters mural here ( see above). The wooden boxes were put up by the City and they have all been covered with art. I was too depressed to carefully document all of them.

On top of the structure was a man on a microphone preaching about Jesus Christ!

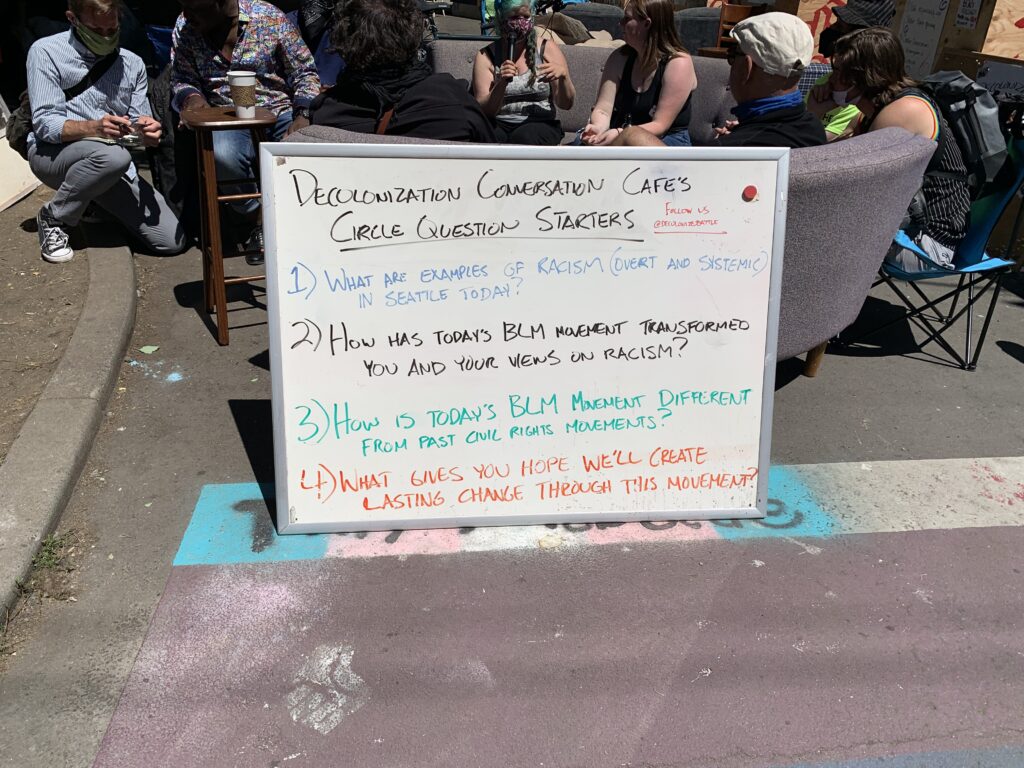

This was a really positive place, Decolonization Cafe. The Seattle Times had good coverage of the CHOP today, June 23 with more engagement with the conversations at the Decolonization Cafe as well as in general. The sign reads “1 What are examples of racism overt and systemic in Seattle today? 2How has today’s BLM movment transformed you and your views on racism 3 How is today’s BLM Movement different from past Civil Rights Movements 4 What gives you hope we’ll create lasting change through this movement”

So I didn’t stop and ask myself these questions and I didn’t sit down and talk. Why didn’t I? They are clearly directed to all of us. What are we individually doing to change the systemic racism of our society?

Storme Weber is a well known poet in Seattle “I told a story until it transformed, I sang a song until the melody lifted, rose from dirge and I could feel the grace notes.”

Somehow this misty image seems appropriate as a way to end. We will see what happens next. The city mayor and police chief, after another shooting, are now wanting the police to come back, and the area to be closed overnight. Hopefully, it can peacefully transition. According to the Seattle Times article cited above, many of the organizers agree with that idea.

Aftermath

June 26 the city brought in Seattle Department of Transportation workers to remove the street barriers. The Mayor and Chief of Police also engaged in dialog with the protestors in a nearby AMC Baptist church ( the oldest black church in the city). Converge Media documented it afterward. They are responding to the demands.

July 1 CHOP highlilghts the ongoing problems in this city, racism, police violence, homelessness, lack of services for addicted and people with mental health problems, gang violence. We had another shooting incident on Tuesday, another young black man killed. Of course it was outside CHOP and blamed on them, but actually this is the same issue over and over. Having police there would only have made it worse, and of course we have the gangs operating all over Seattle all the time and the killings are not investigated by the police. Gangs are also a result of lack of opportunity to be constructive members of societ, poor education, all the problems that could be mitigated with more money in the community.

July 1 midday the police have moved in with teargas and rubber bullets. They are already whitewashing the police precinct. Durkan issued an emergency order at 2am. But as Omari said on Converge Media, this is not going to be the end of the story. The issues are still there.

August 12

Our African American Chief of Police Carmen Best has resigned. I find this depressing. The print headline says ” Budget Cuts, disrespect drove her decision.” The City Council approved cuts in the police department and her salary without consulation.

This entry was posted on June 20, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Intersections in the Chinatown International District: Dim Sum, Seafood and Black Lives Matter

Our unique family-owned businesses in the International District have already suffered from the beginning of the COVID 19 pandemic because of the absurd ideas coming from DC. Then came willful acts of destruction following a protest May 29 not by peaceful protestors, but by outsiders.

But the day after the destruction volunteers began to show up to clean up the glass, garbage and graffitti and to start shopping to show support. On June 5 artists started arriving and painting on the boarded up store fronts. The idea was sparked by Che Sehyun, executive director of Experience Education who reached out to the art community. He raised 10,000. for supplies in five days ( half came from Home Depot for paint) and over 100 artists have signed up. Here is the original call by Che

Che on the left in the yellow shirt. Che is an amazing video artist. Wyking Garrett speaking, leads Africatown, which is fighting gentrification in the Central District, where I live ( as one of the less wealthy wave of gentrifiers from 25 years ago) and Bruce Lee in the background banner.

Last Sunday there was a set of performances by artists to celebrate the project.

Mural by June Sekiguchi with partner Richard Reynolds, on Phnom Penh noodle house on Jackson. June spoke at the program about how the owner of the noodle store survived genocide in Cambodia forty years ago.

This market had one of the most beautiful murals of all. See below

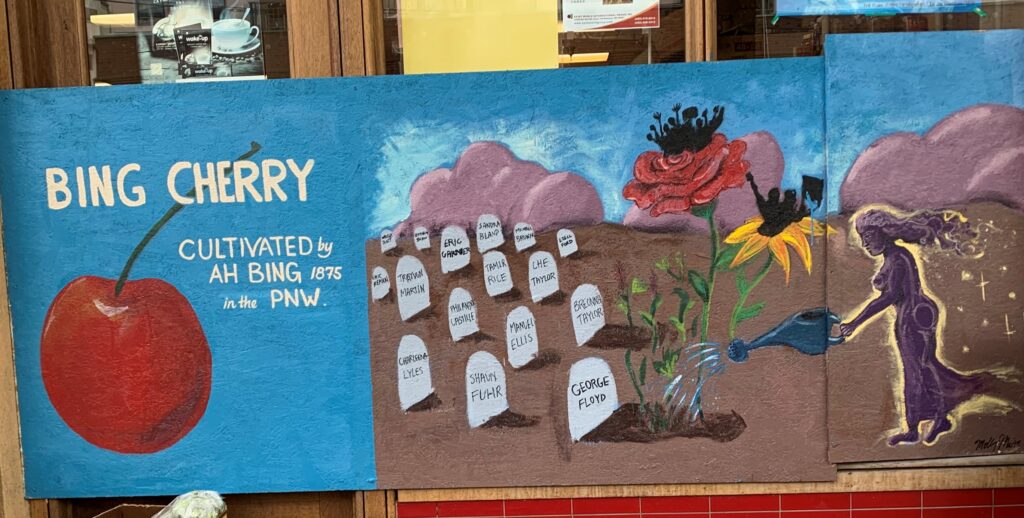

Did you know that Bing cherries were first cultimated in 1875 by Ah Bing in the Pacific North West? Note the mural on the right paired with it, watering flowers in the grave yard of some of those who have died from Police Violence: George Floyd, Shaun Fuhr, Charleena Lyles Mamel Ellis, Bryonna Taylor, Che Taylor, Philando Castille, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Ezell Ford, Michael Brown, Eric Repson, Bethany Jean, Walter Scott ( and the list continues)

This is the type of intersections that I only saw in the ID. BLM plus Indigenous rights. Here are two details “Native Lives Matter”

Jade Garden. Amazing noodle murals

The murals didn’t pull any punches in many cases. In other cases they honored the store or restaurant.

The two above by Kari Sa Morikawa on Vital Tea. According to the Asian Weekly, she is an “amateur” artist. Who would know.

This and the next are by Mari Shibuya with VK Signs. I particularly like their paintings. They did a beautiful mural on Capitol Hill. But it is in the Occupied Zone so it has been graffittied. I will post it on my next blog post about the Capital Hill Occupied Protest.

Above and below, the next group are by Andy Panda and a team of six artists, one of the most beautiful groups in the ID.

Hidden Figures stars.

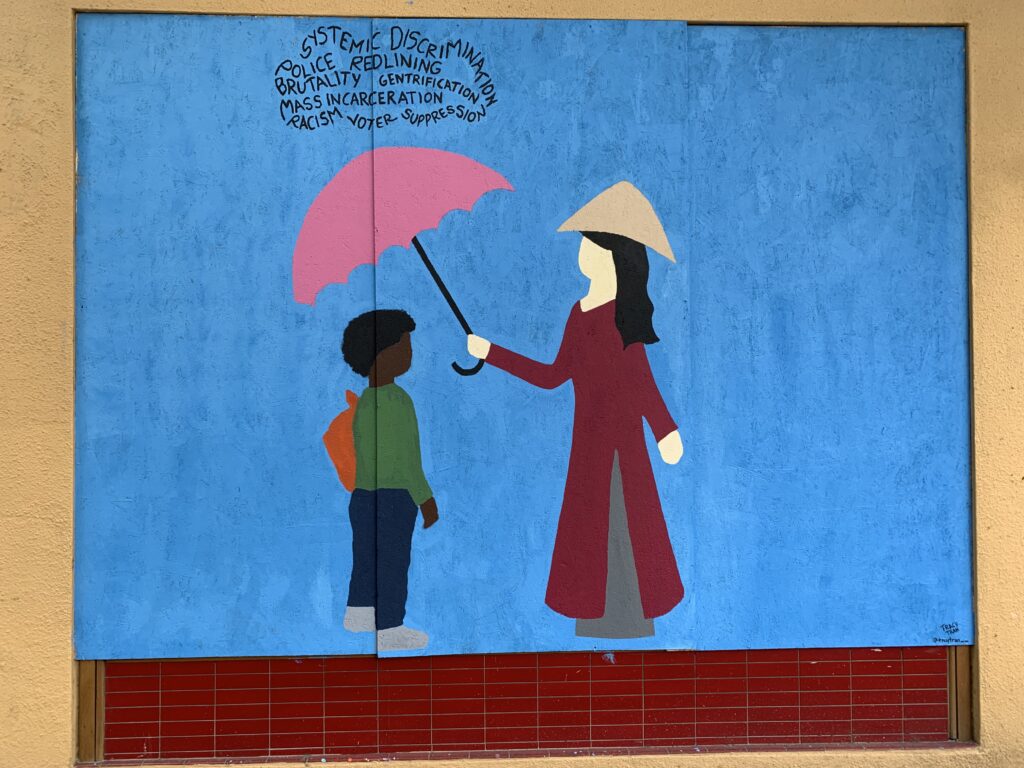

The rain says “Systemic Discrimination, Police Brutality, Redlining, Gentrification, Mass Incarceration, Racism, Voter Suppression ” these two above and one below by Ellen Granstrom with a team of four artists.

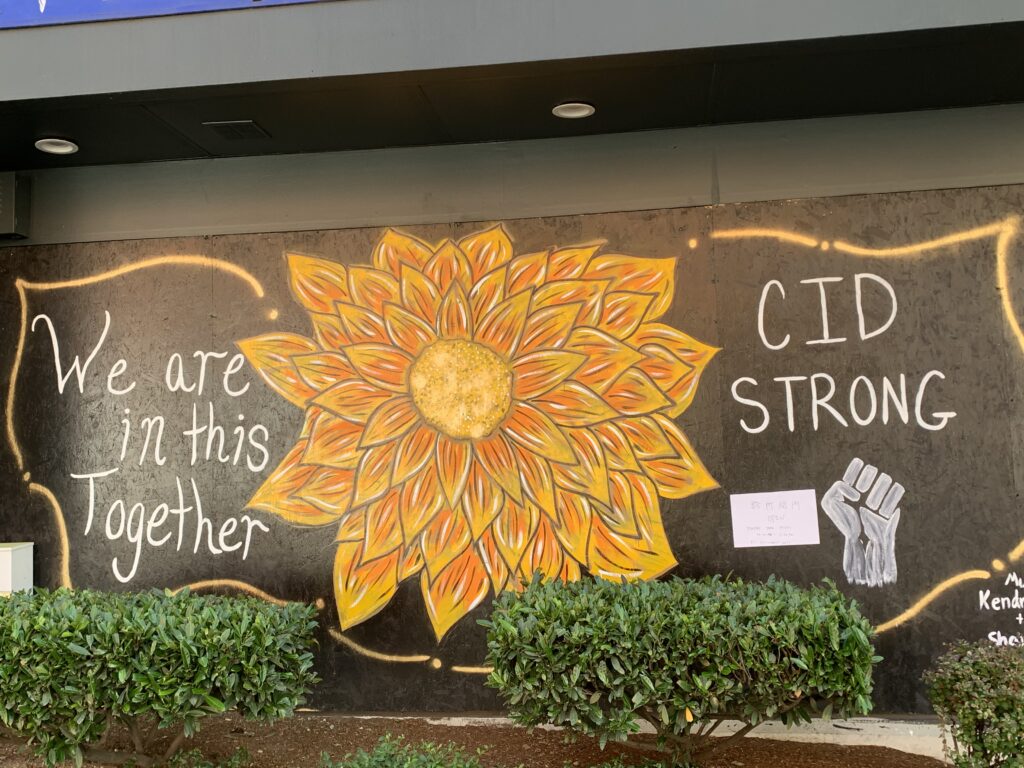

Some were encouraging as in the COVID 19 murals

I just found out the name of this artist, Larsie “Firebird” Freeman. Her mural was in the Seattle Times.

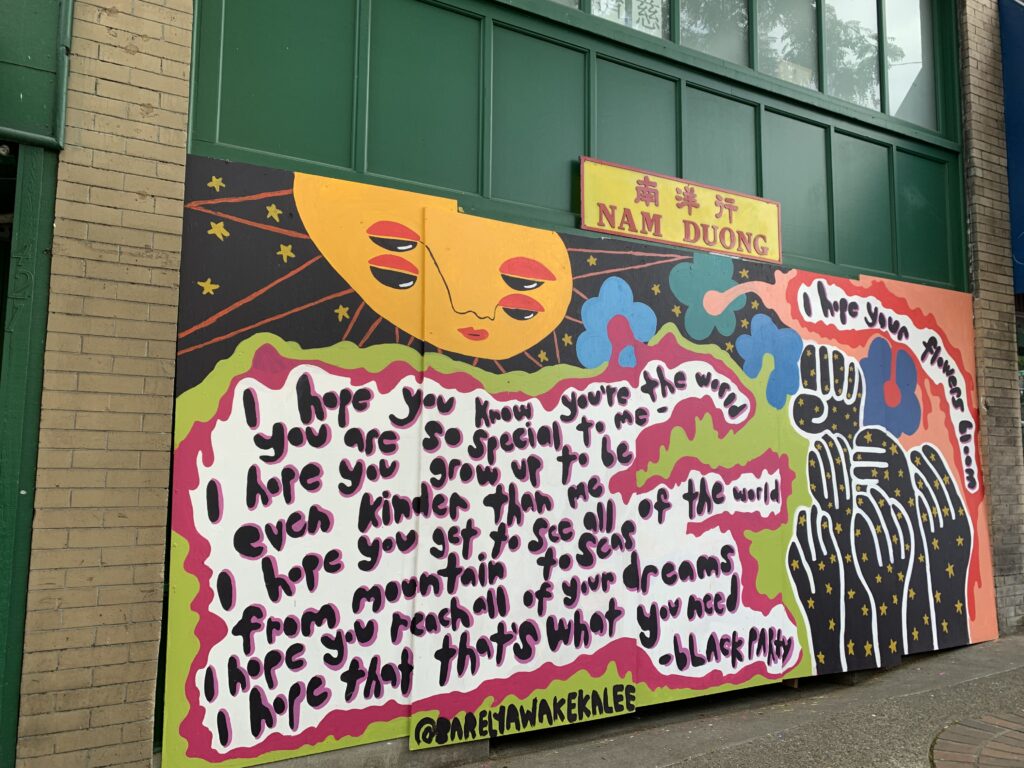

This artist “Barely Awake Kalee” was also on Capitol Hill. “I hope you know you’re the world, you are so special to me….” and other positive statements. Subtle change to simply feeling better by including the black arms on the right?

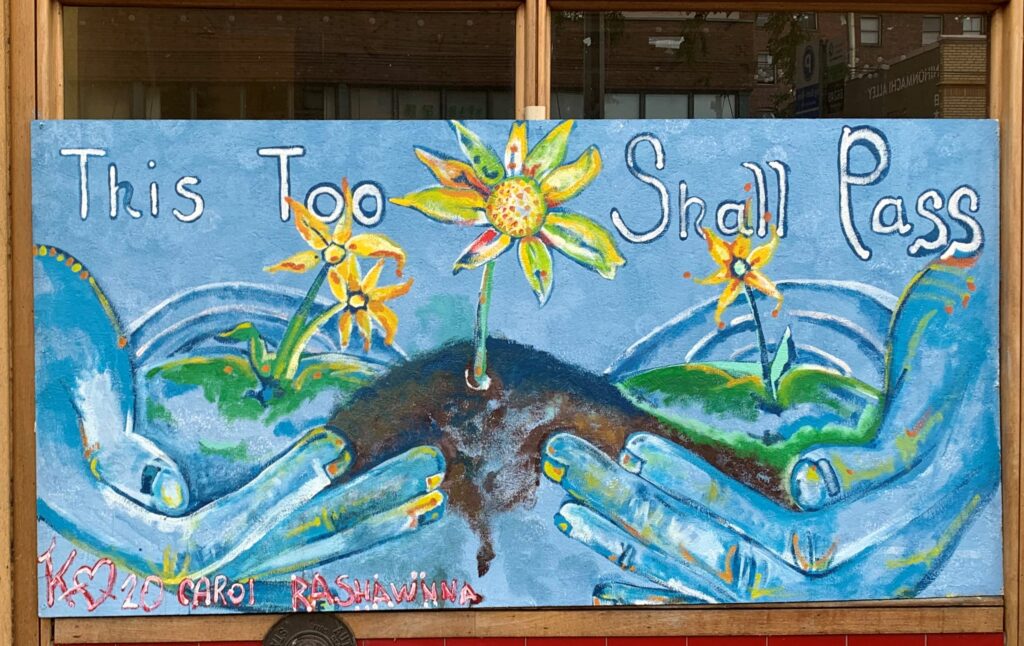

Carol Rashawnna a beautiful nurturing image

These Bush Hotel Murals look like a story of Asian Americans: in this one a child is being taught to farm. The back story on Japanese incarceration is that the Japanese farmers had created a group of farms that produced amazing produce. They were the founding farmers of our famous Pike Place Market ( there is a mural dedicated to them there). When they were sent off to be incarcerated during World War II, their land was mostly taken away by white people. Some people say that was one of the motivations for making them leave. Then when they lived in the desert in a camp, they made that place fertile also, and white farmers took that land over when they left.

In this one he brings some food to his grandfather

In this one he leads his grandfather into Hing Hay Park. @devonmidorisour, Devon Hale.

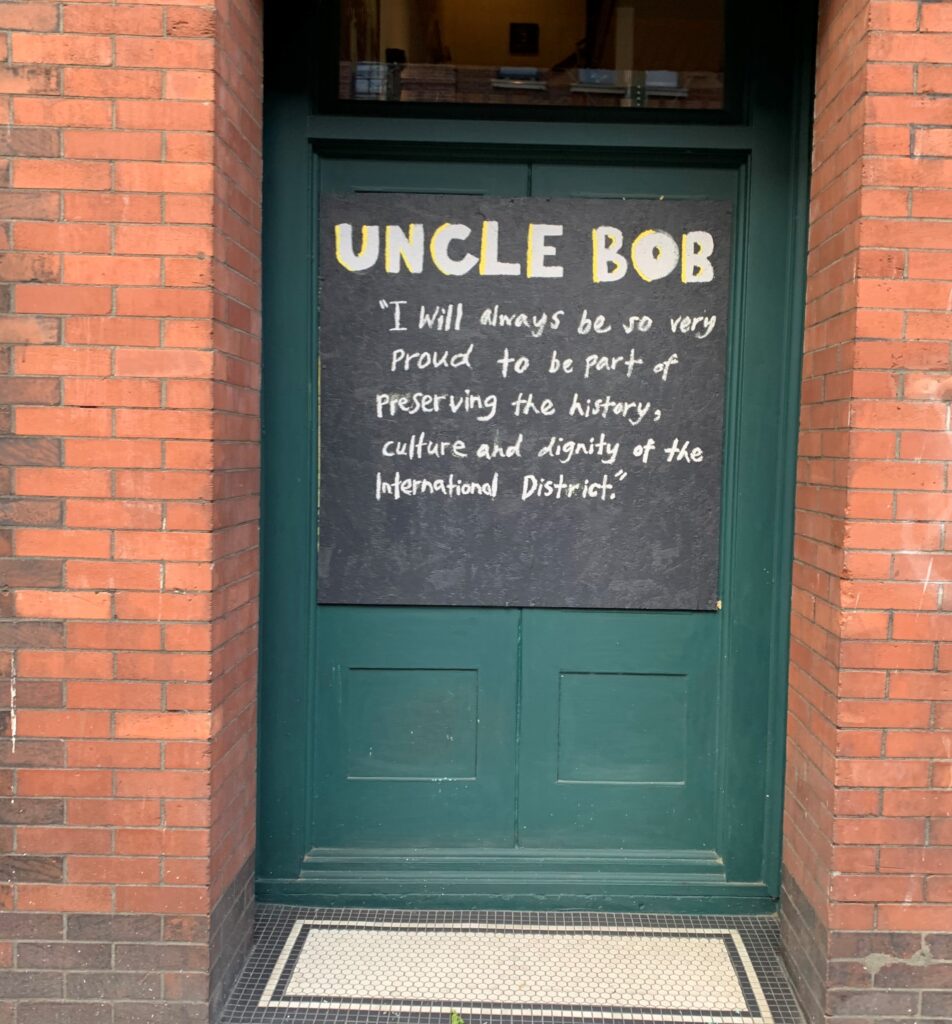

This is a reference to Uncle Bob Santos, the famous international district activist and part of the “gang of four” Seattle civil rights activists Bernie Whitebear, Larry Gossett and Roberto Maestas, a model of interracial friendship and organizing during the 1960s to the present. Only Gossett is still alive. He has made amazing contributions here also.

Santos grew up in Chinatown, the son of Filipinos. He was fundamental to saving the International District .From 1972 to1989, Santos served as Executive Director of the International District Improvement Association

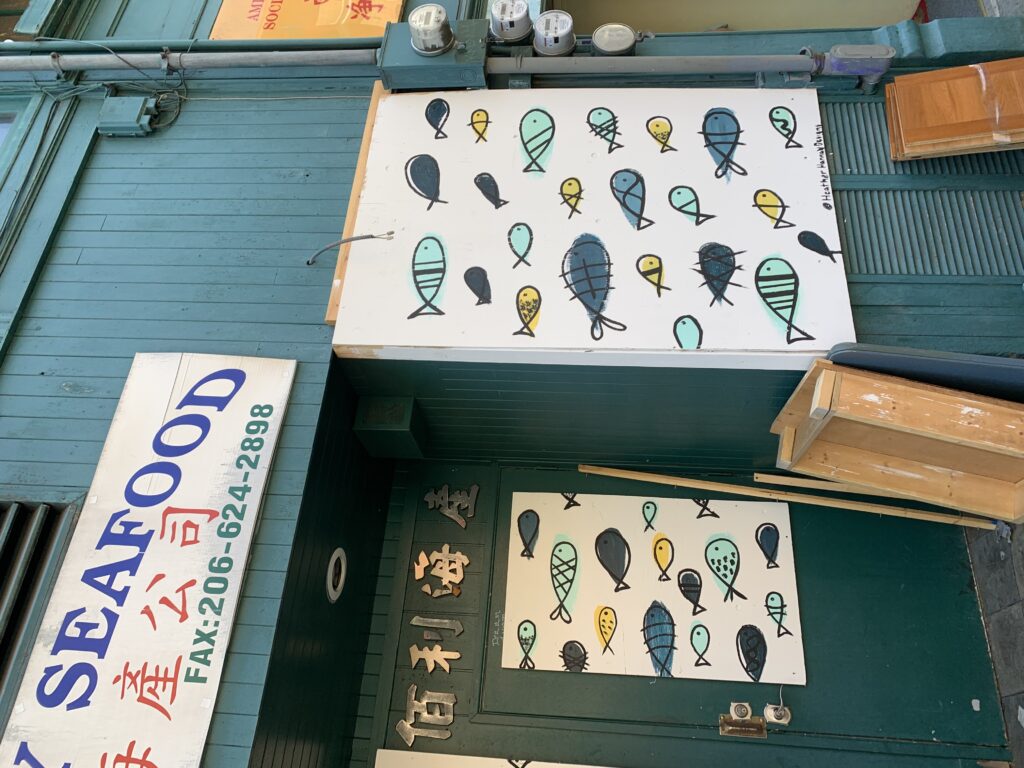

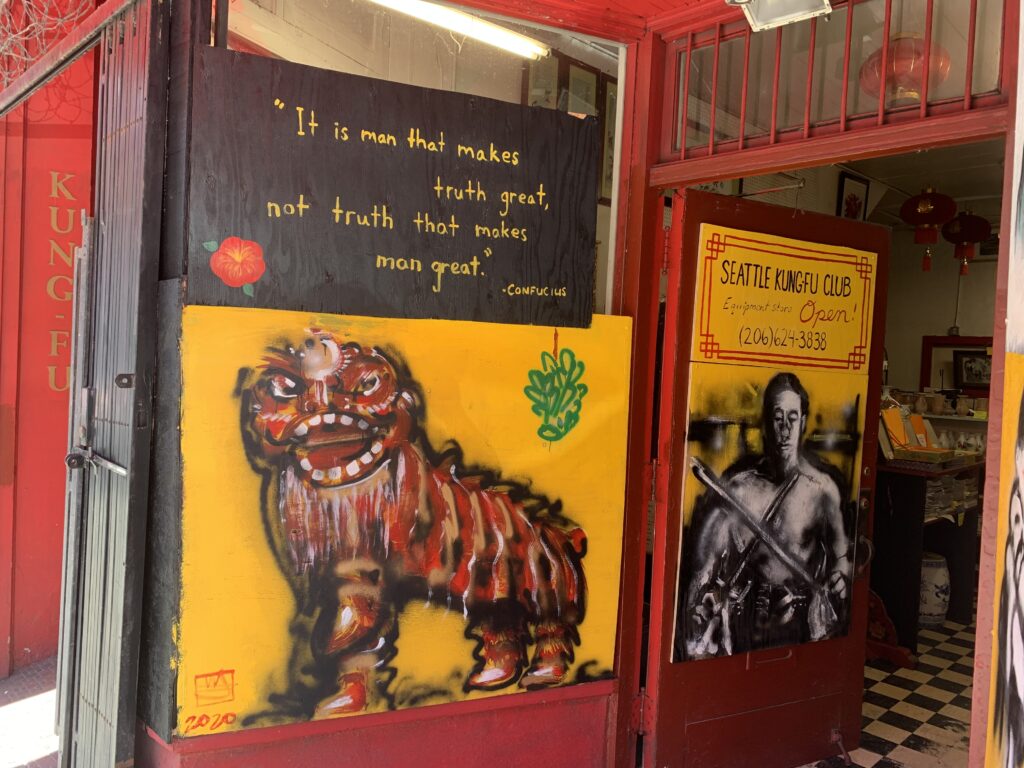

I don’t have a lot of information about the next murals, but they suggest the dazzling variety of styles in the murals, as well as the intersection of Black Lives Matter with the themes requested by the restaurants, groceries, Chinese medicine stores and martial arts establishments of the ID.

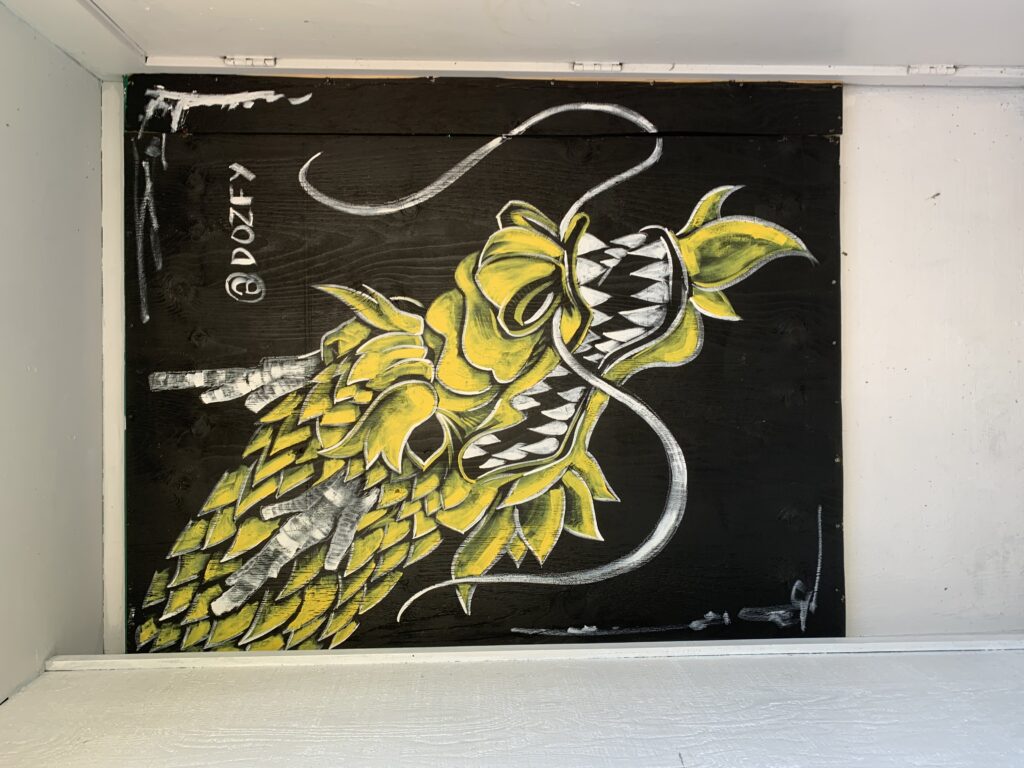

Bruce Lee and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar by Shara and Joseph Lee and Dozfy (Patrick Nguyen). these two legendary actors appeared together in a movie set in Hong Kong titled “Game of Death.”

On this Brazilian Martial Arts Center many different artists participated. Some had never painted a mural before. The one in the center is by an artist who spoke at the celebration. I can’t read his name here, but hopefully coming soon!

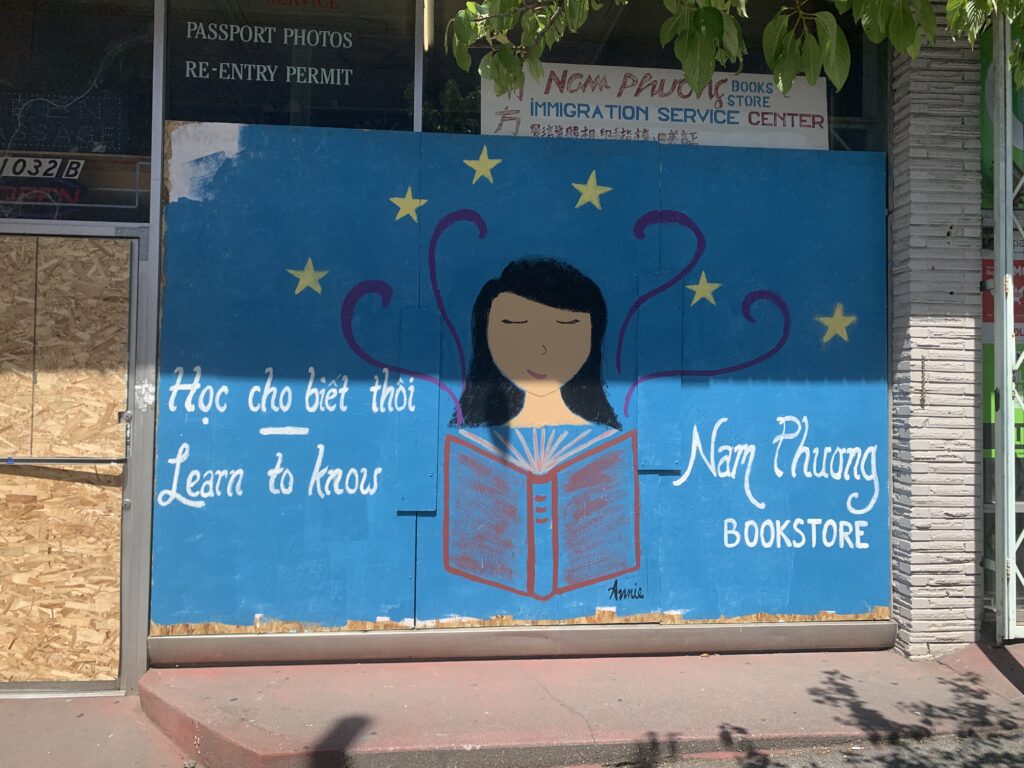

These murals are on the Viet Wah grocery Store. Like so many of the stores in the International District, it is a wonderland of mysterious dried fruits, as well as so many kinds of fish and vegetables.

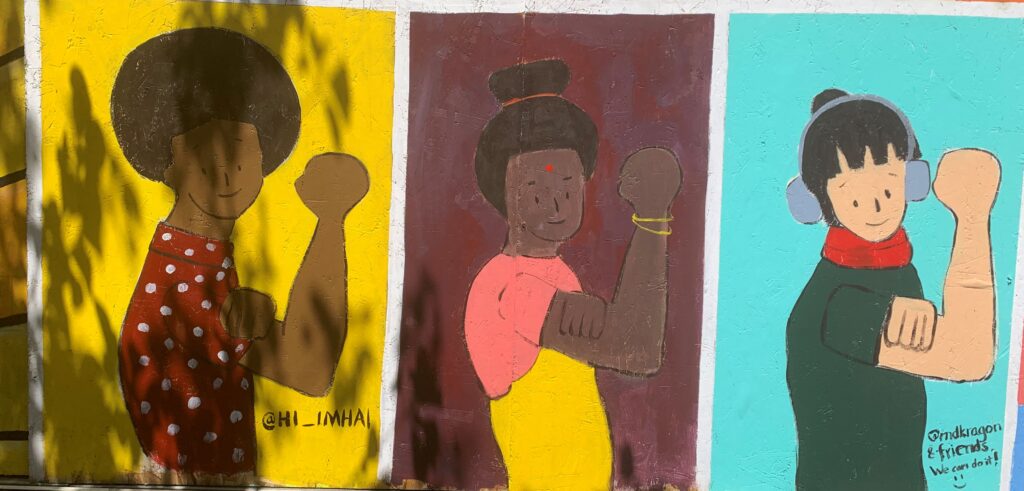

The woman are wonderful, painted by several different artists!

Black Lives Matter fist and a yin/yang symbol, probably unique to the ID!. I ordered lunch from the Fortuna. There are dozens of restaurants to discover in this area. Prepare to be hungry if you go to see the murals!

Kendra Azarai and her daughters on the Iron Steak restaurant.

as well as on this doctor’s office.

Sydney Pertl with her amazing lobster and crab. She learned some Chinese Calligraphy to be able to write here in Chinese!

Here is Patrick Nguyen (Dozfy) He is part of every mural cycle I have recorded in Seattle. Great artist.

Taken together, this project stood out for its diversity of artists and intersections of themes. It also introduced me to more of the small shops and groceries of the ID. I can’t wait to go back soon. Please support these businesses by going for a look at the murals and stopping for a bite to eat. They are all open!

This entry was posted on June 18, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

Seattle after George Floyd Murder: Protest, Anger, Marches, Occupation

We have had a 180 turn in mood in the last two weeks, as a result of the murder of George Floyd. I am now seeing the anger about racism and police violence leading to demands to defund the police, whereas before we were “all in this together” to stay home ( which of course also laid bare racism, as privileged people, predominantly white, stayed home, and people of color went to work for minimum wage and risked their lives.) Even as we march, more black men are murdered. Here is the most recent Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta. We can see on the video the terrible training , the excess arms, the hostility .

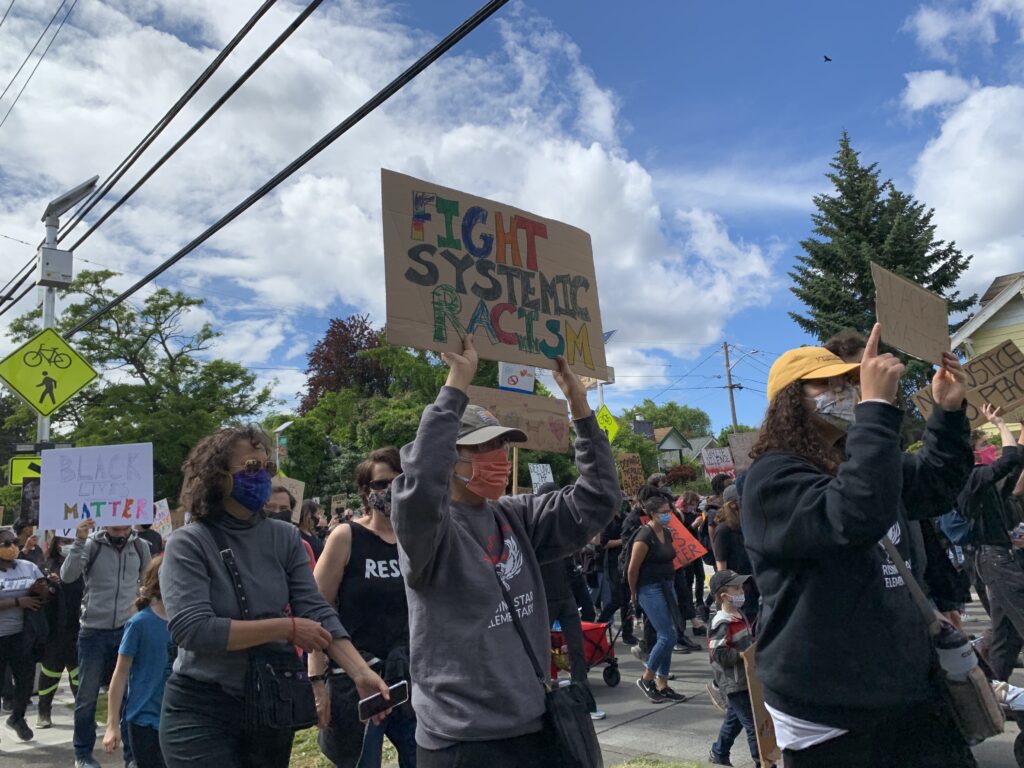

Huge amounts of new visual imagery has emerged in the streets and on the walls of Seattle some of it actually on top of Covid murals documented in my three previous posts. The city has turned inside out.. Art and personal expressions are everywhere, not confined to galleries or trained practitioners.

We have had enormous protest marches almost daily. Many of them have been to and from downtown, well covered in the Seattle Times. Here is one excellent article by Naomi Ishisaka whom I saw at the “We Want to Live” March right after she had this front page story. Naomi is normally a once a week columnist on Monday. I asked her if she was paid triple for this two page article and she said no. ( Is that discrimination at the Times?).

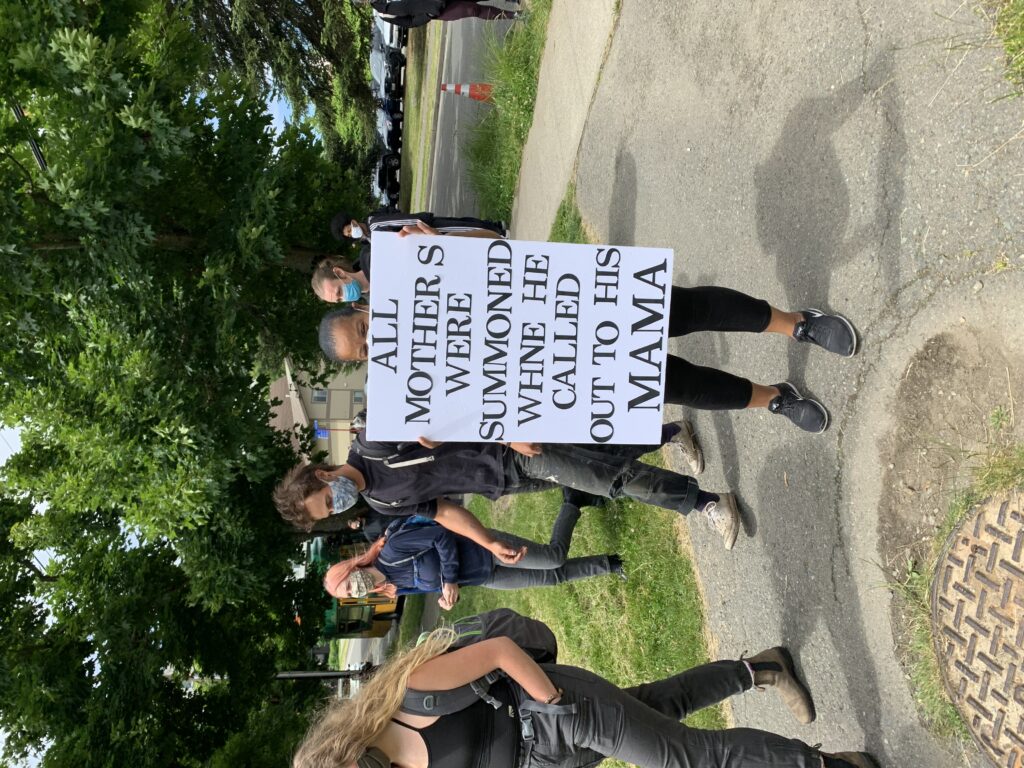

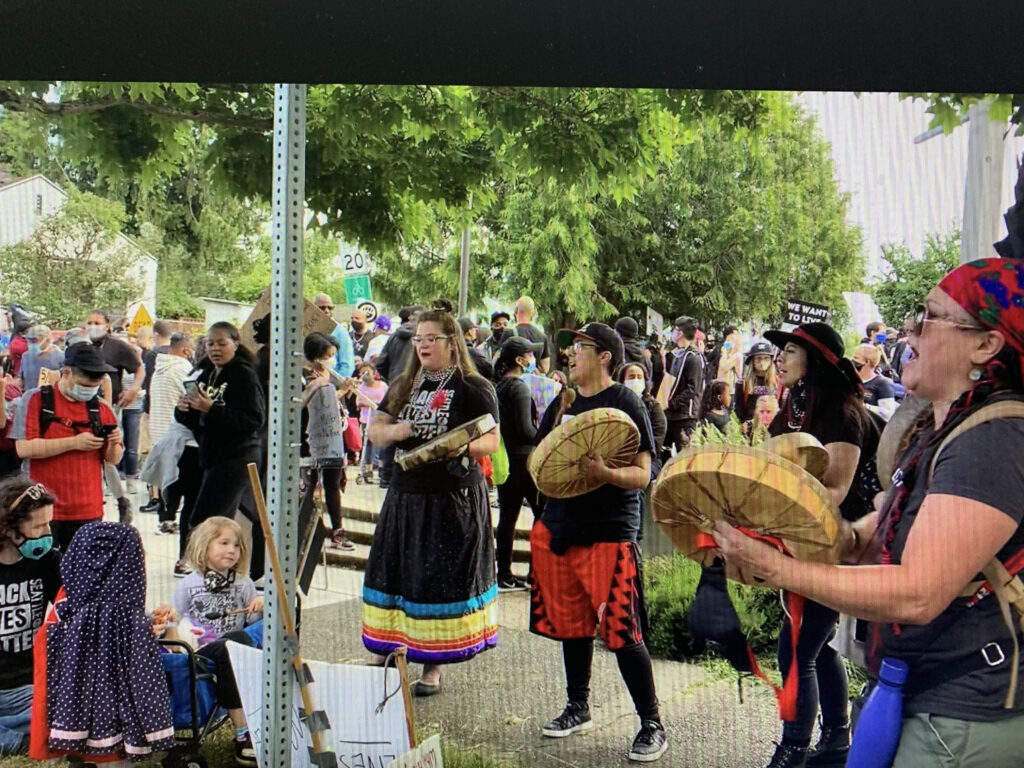

I have been to two of the protests, “We Want to Live” on June 7 starting in Othello Park and the “March of Silence” on June 12 starting in Judkins Park. The first one was very large, with lots of families, all ages, ethnicities, the second one was huge, in the pouring rain, and perhaps fewer families because the next day was a march for children which unfortunately I missed. I took lots of photographs of the marchers. The most moving event for me was standing in silence for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. It was an incredibly long time. Incomprehensible, tragic, heartbreaking.

But also moving was when the entire crowd of thousands began to move in absolute silence. It was a river of silent bodies.

I will first focus on the two marches for imagery. In the next posts, I will talk about the amazing International District murals and the transformation of Capital Hill to the “Capital Hill Occupied Protest”

The “We Want to Live March” had small posters with that mantra that could be filled in with a person’s name, as well as photographs of many people killed by the police.

When I first arrived I saw this sign. It is so moving. It was one of the repeated statements of the march. It matched the larger theme focusing on youth.”We want to Live”

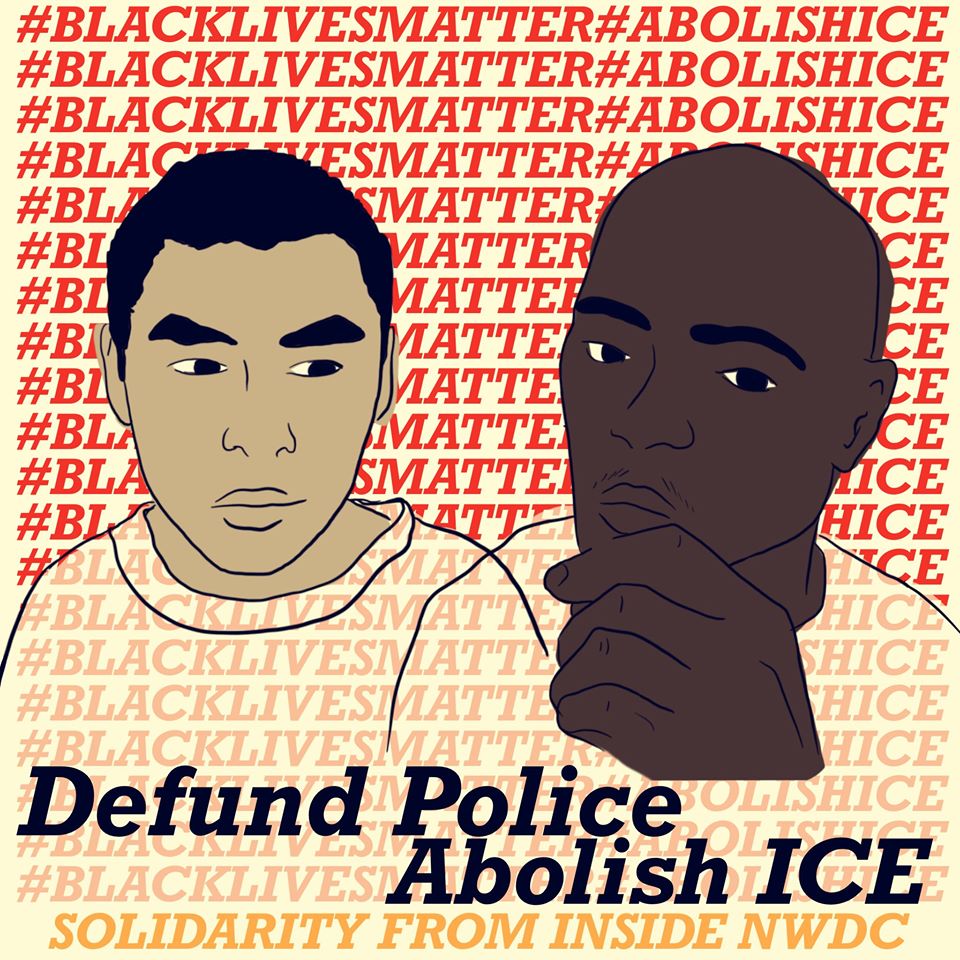

There were definitely over a thousand people there and many different signs, but the emphasis was on “we Want to Live”. Youth led the march holding a huge banner with the statement “We Want to Live”. I was looking for intersections of all the racial groups. “Black Lives Matters” encompasses all people of color. Here is an image sponsored by La Resistencia for example. The detention system was breeding despair and destruction of families before the pandemic, now it is killing people. Call Inslee to shut down the detention center and free all the detainees. THey are not criminals. Follow the link for instructions.

Latinos for Black Lives in the March.

Black Lives Matter Native American Drummers. Hopefully I will learn how to post my video of this.

Pasifika for Black Lives

And families with children

“Why Do You See Me as a Crime?”

I am sorry I cut off the slogan held by the young man kneeling, but you know what it says.

And then there were many many other people who care enough to create this long people’s outpouring of words protesting police violence

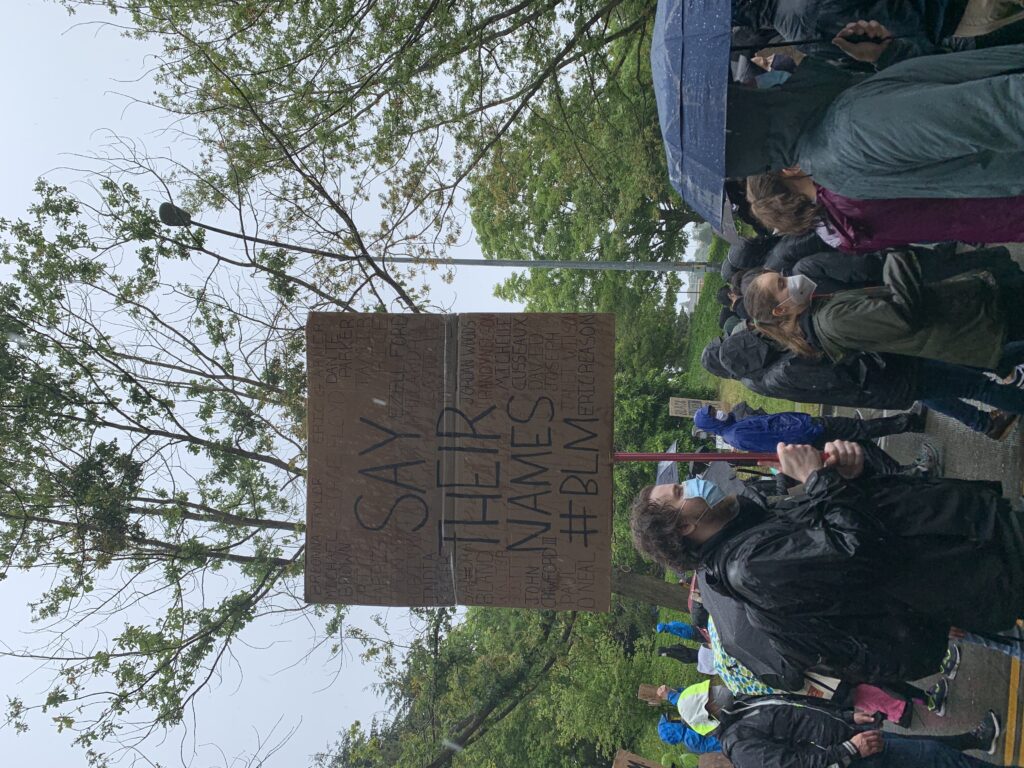

The second march I went to was the “March of Silence”, already described above.Organized by Black Lives Matter King County, it was much larger than the “We want to Live March,” because it was on the day of the national strike June 12th. I will post a few images from it. It is not possible to convey how moving it was to stand in a crowd of thousands who were all silent both during the moments honoring George Floyd’s death and in the march itself.

South Asians for Black Lives

And it was pouring rain which seemed so appropriate to our silence in honor of all of these people brutalized and killed by the police.

This final image is actually from the Capital Hill Occupied Protest, but it gives names and ages and some of the people who have been murdered. Since “Say their Names” is one of the signs repeated on every march, I include it here. This is the only sign I saw with the ages of the people killed. At the top is Charleena Lyles, killed in Seattle in her apartment, mother of four.

Below are the names and ages of George FLoyd age 46, Breanna Taylor age 26, Ahmad Aubrey, 25 Eric Garner 43,Michael Brown 18, Tamir Rice 12, Freddie Gray 25, Philando Castille 32, Stephen Clark 25, Trayvon Martin 17, Manuelle Ellis 33, Charlene Lyles 30

This entry was posted on June 17, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

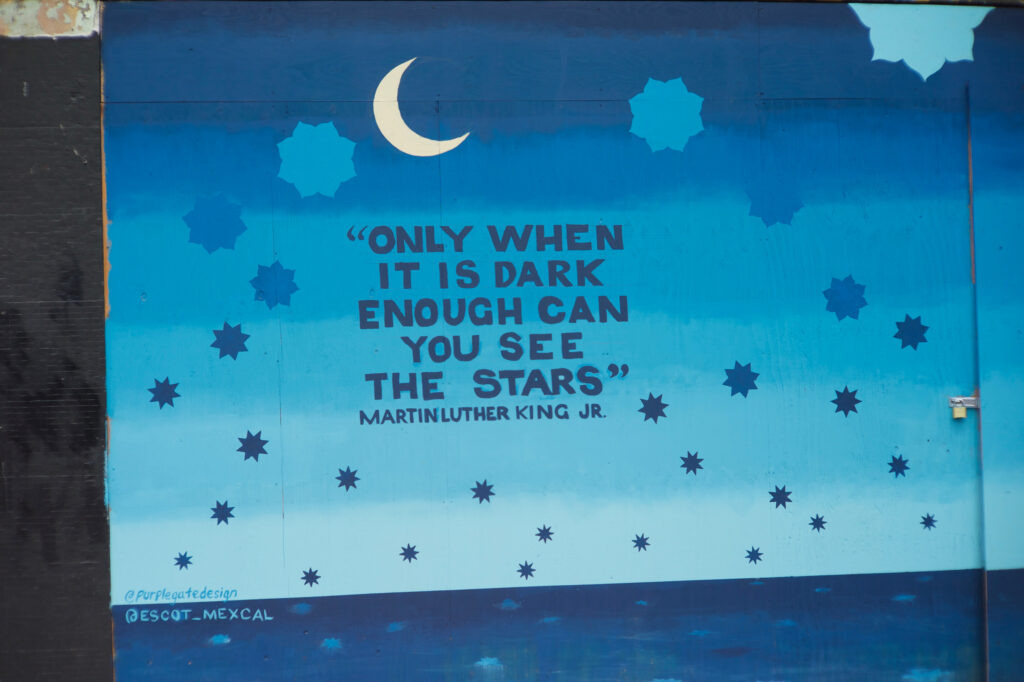

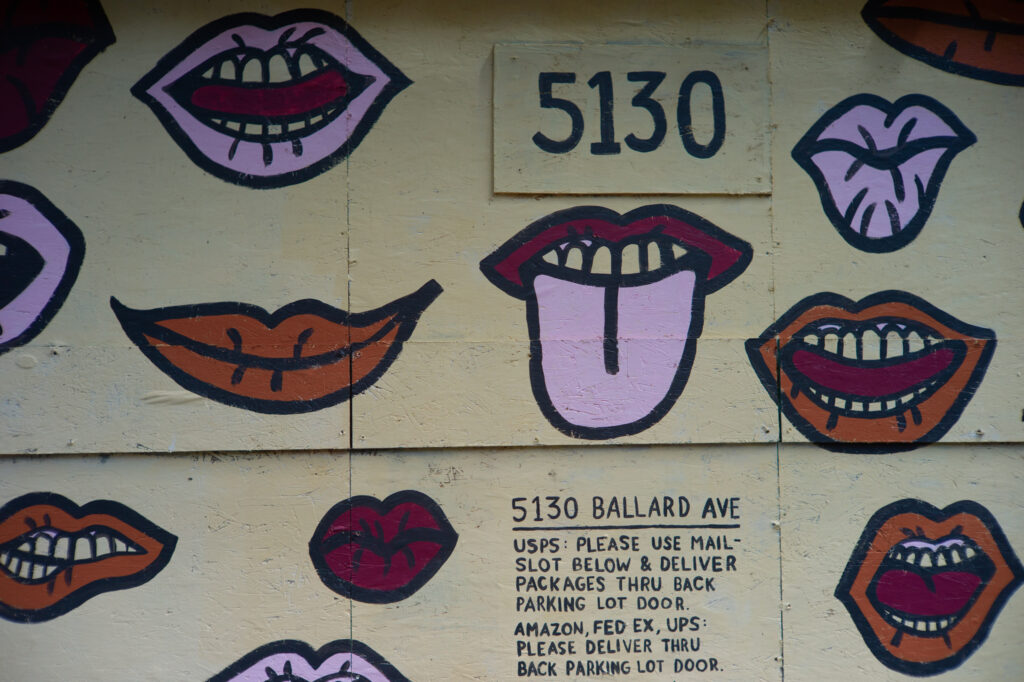

Covid 19 murals in Seattle: Ballard

This is the only series of photos that I didn’ t take myself. Ballard seems far from where I live. So I asked around and put together these images. Thanks to Jeff Hou and Sean Yale. But of course they are not in any particular sequence and Ballard seems to have the least online presence of these three neighborhoods. If there was no signature visible I left it blank. Maybe someone will let me know who did the unidentified murals.

This entry was posted on May 22, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.

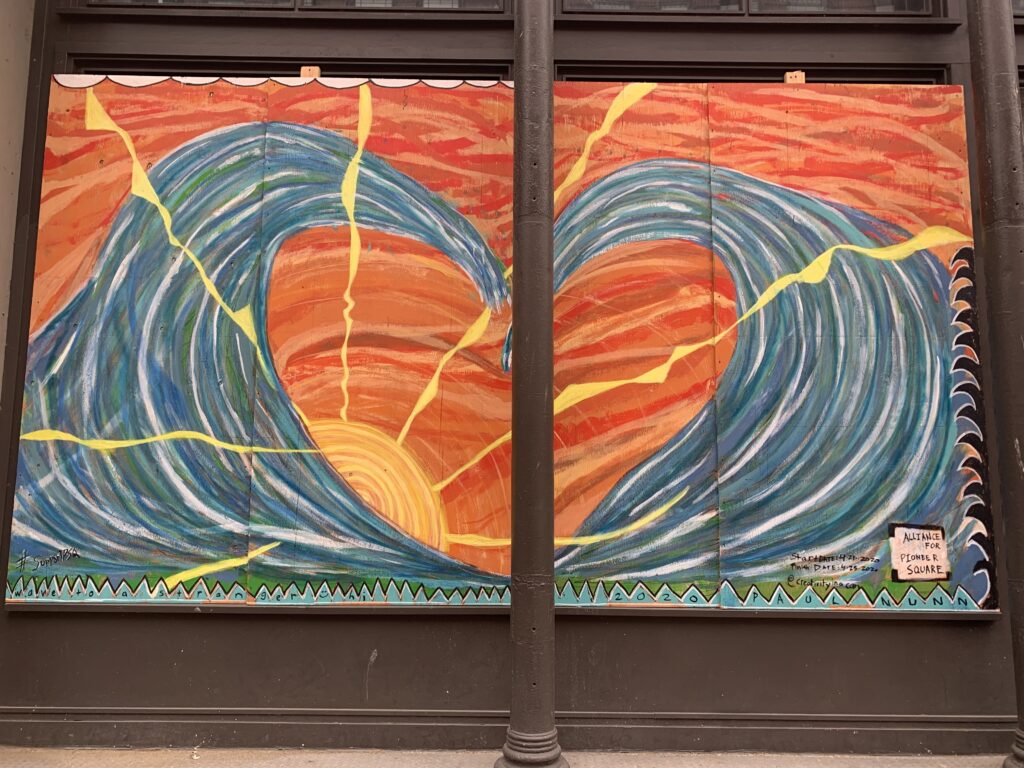

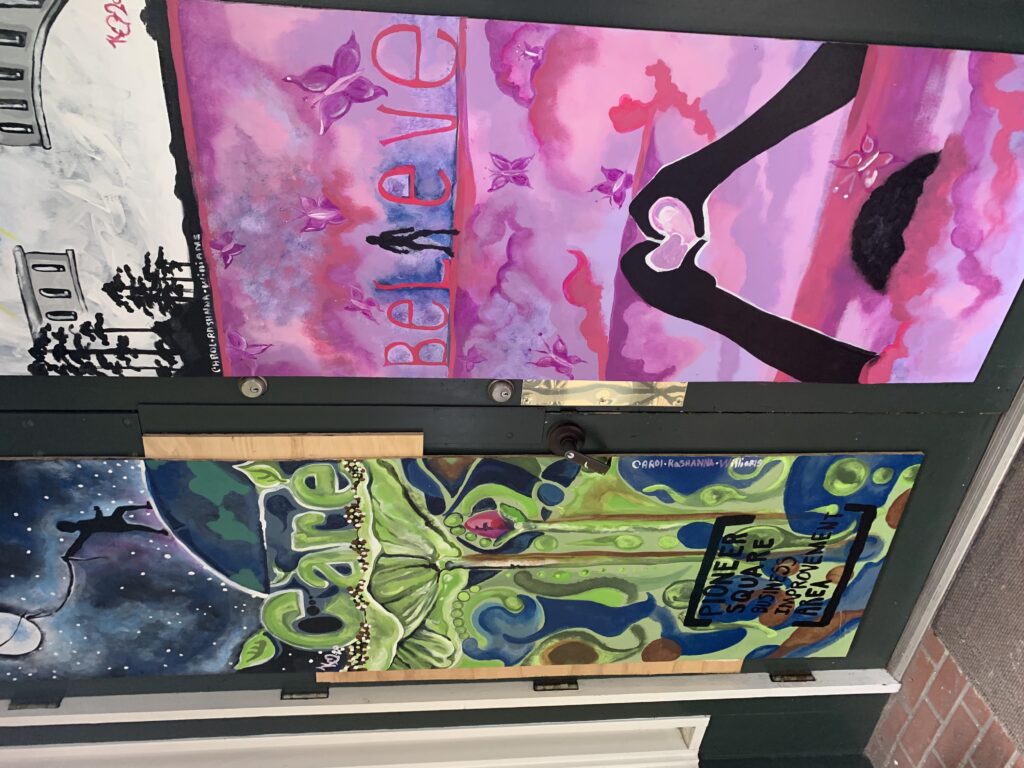

COVID 19 murals in Seattle: Pioneer Square

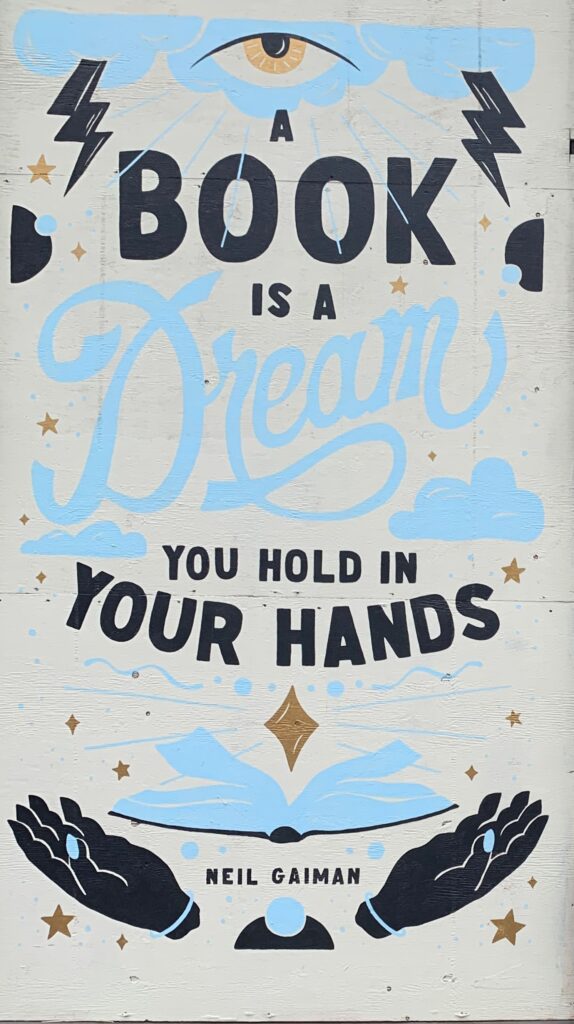

Pioneer Square has many many murals. I photographed a few of them and then discovered there is a walking tour which identifies a lot more of them. They are sponsored by the Alliance for Pioneer Square and Pioneer Square Business Improvement Association. In the case of the Globe Bookstore, the owner reached out to a specific artist, Sam Day ( whom I just discovered does the great cartoons in Real Change).

That may be true for other artists as well. According to one person I spoke with, many of these artists work in Pioneer Square and they are being paid a lot to make these paintings. That is interesting. I have not asked any of the artists I have met what they are paid, but I know there was a go fund me page for some of them.

What is terrific is that we are seeing art all over the place. Anyone can go out and enjoy these paintings as you start to move outside your neighborhood. Ballard is coming next, and Georgetown! .

Where I could find the artist I have added it. I will just present them as I saw them ( keeping in mind that I missed a lot, so look at the walking tour for more information and imagery). You will see the wildly contrasting styles of the artists. Below is the Buttick MFG Co with its huge mural by Jonathan Wakuda and Wakuda Studios stretching around the corner.

Door: Michelle Obama, Langston Hughes, John Siscoe ( back to us)

Right Panel: Sherman Alexie, Maya Angelou, Jamie Ford, Samuel Beckett

This entry was posted on and is filed under Uncategorized.

COVID 19 mural art on Capital Hill May 2020

This is an introductory essay on the mural art in Seattle that is filling the boarded up windows of so many stores. I need to do a lot more research on the artists and the sponsors, but here I will simply post the murals I saw yesterday. I spoke with one artist Tara Velan who was working on a mural as I spoke to her, and I spoke to one sponsor, Oddfellows Hall, who explained that they put out a call and paid the artists.

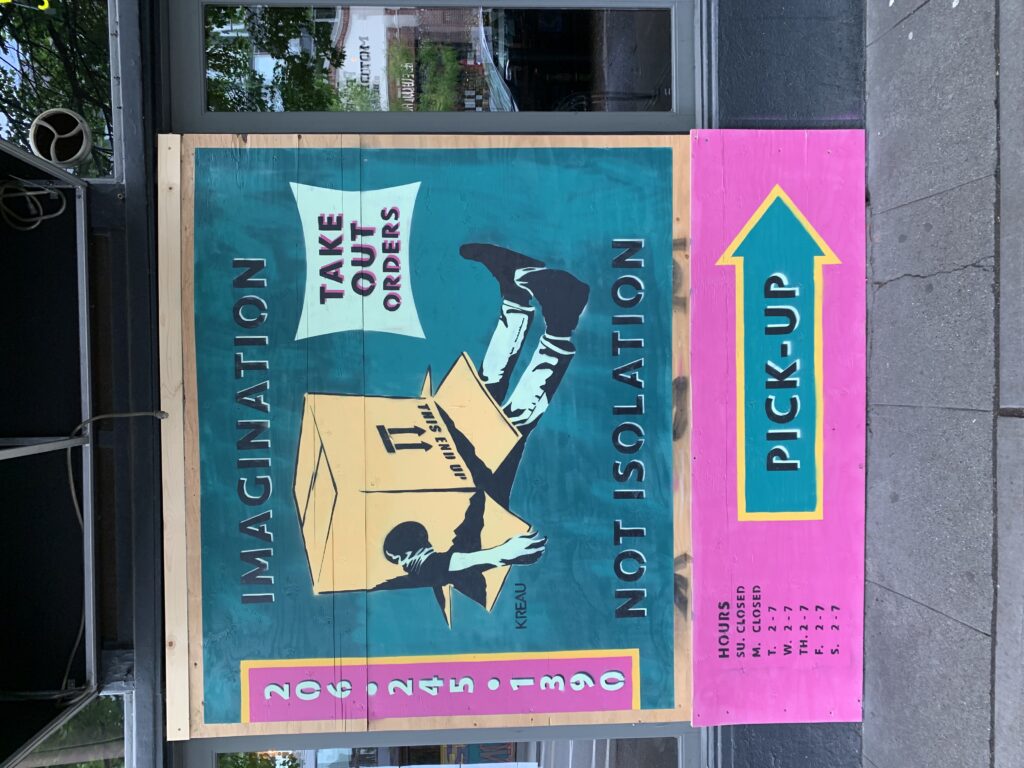

More to Come. Here are the murals. They range from subtle work to pop, from highly trained to graffitti. As a person who has written about mural art in the 1930s and 1960s, the first era inspired by Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jose Clemente Orozco, the three great Mexican muralists, the second era partially by Judy Baca, who studied with Siqueiros, it is clear we are in a new era today.

The artists draw from many directions, but there is no larger political message/ philosophy that I saw. No anti capitalism or references to the failures of the government, or underlying issues. The murals are of course on the windows of stores, but they are small businesses in grave danger of disappearing, so a larger message seems possible, but perhaps not what these stores want. Perhaps when I venture down to Pioneer Square, I will see a different story.

On the other hand, collectively they create a strong message of solidarity that we all can benefit from at this moment, even though few people are actually walking on the street. I have simply put up all the murals I saw as I walked down the street, no editing, no curating! You will see how many different styles appear. And our current pandemic has its own iconography such as”Tiger King.” which will be available for future art historians to puzzle over.

This entry was posted on May 10, 2020 and is filed under Uncategorized.